The first thing that was blowing my mind about Short Circuit was not just, how could there have be a Johns Flag before the first [sic] Johns Flag, but how could there be a missing Johns Flag? I mean, seriously, wouldn’t that be rank just below the Gardner Vermeer in terms of stolen art? How could it be missing and the entire art world not have its eye out for it?

In fact, it’s just the opposite situation, where, when they’re not ignored completely, the stories of Short Circuit and its flag painting are misunderstood, misrepresented, and relegated to footnotes. It just didn’t make any sense.

But it also seemed that as long as Short Circuit was ensconced in Rauschenberg’s own collection, and Sturtevant’s replacement flag was in place, no one had ever undertaken an actual search for it, or an investigation into what had happened.

And given the nature and history of the relationship between Johns and Rauschenberg, and the extraordinary custody agreement they reached, which Johns wrote about in 1962, to never show, reproduce, or sell Short Circuit, it’s always been an open question to me whether the flag was actually ever “stolen,” or whether it was just missing. Or removed. Or disappeared [in either the transitive or intransitive sense of the word.]

The question I ended my first Short Circuit post with 18 months ago, which should have been the easiest question to answer, turned out to be one of the most complicated: Was the Short Circuit flag ever registered as stolen?

The first and shortest answer was no.

Tag: short circuit

Jasper Johns’ First Flag

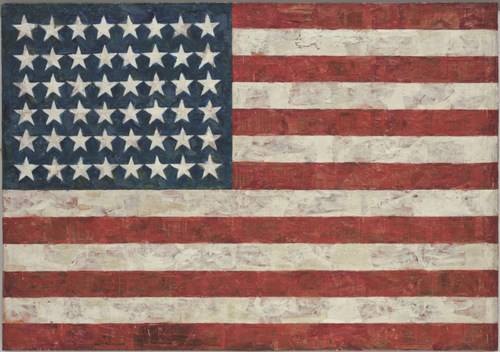

Flag, 1954-55, collection and image: MoMA

When, after a couple of weeks of poking around, I didn’t stumble, Banacek-style, onto the Jasper Johns Flag painting from Short Circuit, and then flip it for my 5%, reunite it with Rauschenberg’s combine, and get on the front page of the Arts & Leisure section again [ahem], I did kind of wonder what the end game of this search might be.

At some point might the result just be an acknowledgement that the flag is lost, fate unknown? And if so, does it just remain an entertaining art mystery, but a footnote to the “real,” relevant history of Johns’ and Rauschenberg’s work and all that flowed from it?

Fortunately, I don’t think that’s what happens here. No matter if it never resurfaces, the Short Circuit flag deserves a place in art history as the first Flag Johns showed, by almost three years. It is also almost certainly the first Flag Johns made. Which is tricky, because that distinction is commonly given to THE Flag, at MoMA. But I think I have figured out that that is chronologically impossible. Johns may have started MoMA’s Flag before Short Circuit‘s, but he certainly didn’t finish it first.

Here’s the deal:

The date for MoMA’s Flag has always been in flux, but it has almost always been considered or assumed to be the first one he ever made. The disappearance from public view of the Short Circuit flag after 1962 greatly facilitated this conclusion.

‘Combine Paintings’ And Pillow Talk

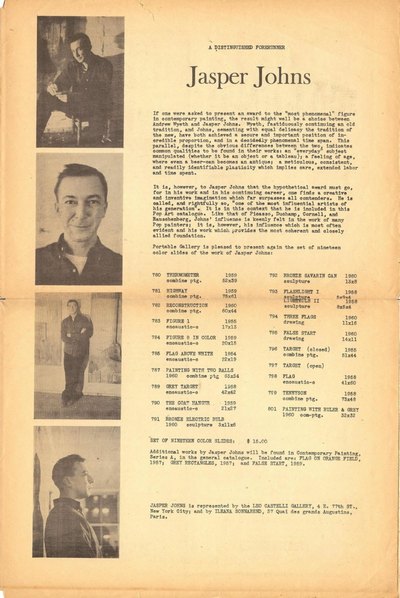

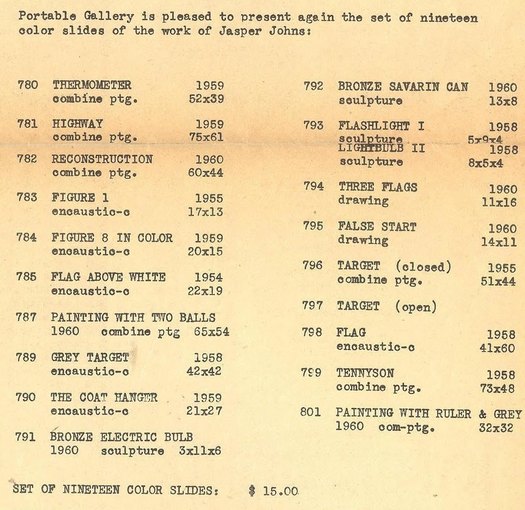

Oh, now that’s interesting. I can’t find an actual print copy of the Portable Gallery Bulletin anywhere, but Joel Finsel has scans of a couple of pages in Swimming Naked At The Y, his biography/oral history blog about Edward Meneeley.

image composited from scans at Joel Finsel’s Swimming Naked at the Y

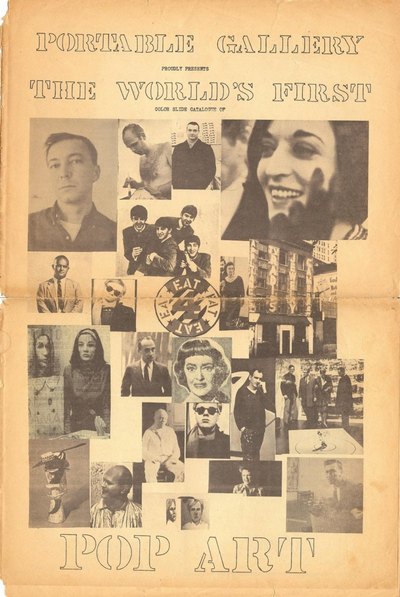

One example: the Jasper Johns page from what they called “The World’s First Pop Art Newspaper,” but which is actually titled “The World’s First Color Slide Catalogue of Pop Art.” Given the Beatles reference, I gather it was published in early 1963, a full five years after Johns’ groundbreaking solo show at Castelli, but before his Jewish Museum show. And after his bitter breakup with Rauschenberg, and after he’d written PGB a letter describing his and Bob’s agreement to not show, sell, or publish images of Short Circuit:

Dear Sir,

I’ve always supposed that artists were allowed to paint however-whatever they pleased and to do whatever they please with their work–to or not to give, sell, lend, allow reproduction, rework, destroy, repair, or exhibit it…

That quote has stuck with me like glue ever since I read it, all through Cariou v. Prince, and right on through to Gerhard Richter’s destroyed paintings. But more on all that later.

PGB’s text is a little over-the-top, I’m afraid, not terribly meaty critically, but then, it was really designed to sell a box of color slides for $15. This was the collection from which Short Circuit was excluded. Or maybe it was the slides of Bob’s work, who knows? Anyway, it didn’t happen.

Point is, check out the works that were included:

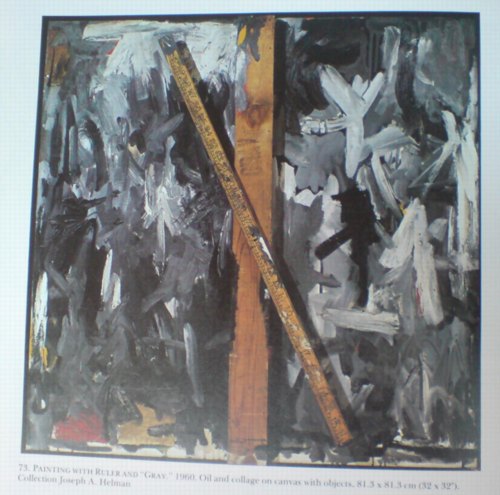

Thermometer (1959), Reconstruction (1960), Tennyson (1958), Painting with Ruler & Gray (1960), [below] and going all the way back to Target (1955), are labeled as “combine paintings.”

Painting with Ruler and Gray, 1960

But combine paintings are what Rauschenberg made. It reminds me of something in Calvin Tomkins’ 2005 New Yorker profile of Rauschenberg:

Johns recently told Joachim Pissarro, a curator at MoMA, that he thought the term “combine” had been his suggestion. Pissarro asked him what he thought it meant, and Johns said, “It’s painting playing the game of sculpture.”

Rauschenberg doesn’t recall that the word “combine” came from Johns.

I’m sure.

There’s more that article, including Rauschenberg telling Tomkins that “the most important thing” he got from Johns was not the combine or, say, the title, crucial Wittgensteinian graphic element, and entire conceptual construct of Erased de Kooning Drawing, but “Courage. Persisting upstream.”

But that’s not the point, at least right now. It’s just that an early stage in Johns’ career, someone who knew him and Rauschenberg well was writing about his work using a term that is–or became–associated exclusively with the work of his former partner.

Tennyson, “encaustic and collage on canvas,” and Bed, “Oil and pencil on pillow, quilt, and sheet on wood supports” [image, right: moma]

I’ve often thought that a lot of Johns’s 50s and 60s works looked and felt like combines, but I’ve never seen the term applied. To take only a recent example, combines are only mentioned twice in the catalogue for the amazing 2007 show Jasper Johns Gray, both times by the Art Institute’s James Rondeau and both only in reference to Rauschenberg’s work. One was a “tender” and “unsupported” interpretation of the two-panel Tennyson as a double bed, “Johns’s own, wildly restrained response to Rauschenberg’s Bed, a landmark combine painting made two years earlier.”

Bed is, famously, paint on an actual pillow, sheet and quilt, making references to both AbEx and Albers-style geometric abstraction. Tennyson, meanwhile, is two Bed-size canvases pushed together, with pillow-like shapes on top [Rondeau shows how these pillows are given volume and shape in Tennyson drawings] and another, separate canvas laid face down across them like a blanket. And all covered with gestural abstract brushstrokes.

These works don’t have to be exactly the same, with handwritten footnotes on the back, to be seen as relating to each other, do they? Artworks made next to or around each other during the artists’ most important, intense, insular, and productive relationship? How is it possible, or more precisely, why is it the case, that no one in 50 years has considered Johns’ work as “combine paintings”? What would be different if we did?

In The Backroom With Jasper Johns

Well this is interesting. I don’t know how I missed this before now, but Albert Vanderburg was the associate editor of Portable Gallery Bulletin whose 1962 article discussing the impact of Rauschenberg’s inclusion of Johns’ flag painting in Short Circuit prompted Johns to write in. According to Vandenburg’s own recollection, that’s not all it prompted:

We had behind-the-scenes access to many museums and galleries and came to know many artists we might otherwise never have met. It was often necessary to move paintings in order to properly light and photograph them and it was a touching experience sometimes to see the backs of famous canvases. Ed had the habit of photographing any interesting work he spotted in back rooms even though I sometimes grumbled over the shambles it made on the production end. The negatives were printed in reels the size of a motion picture, then cut frame-by-frame and mounted in cardboard holders, so a beautiful Picasso sandwiched in between Roy Lichtenstein and George Segal exhibitions didn’t make for efficient processing, not to mention packaging and promotion which meant all those interesting individual items had to eventually be found a spot in the catalogue with suitable companions since we had long since given up selling individual slides.

One of those backroom items created another of my stormier sword-crossings with the Powers That Be. Before Jasper Johns appeared publicly on the scene, Robert Rauschenberg had created one of his “combine” sculptures which included a small all-white example of the American flag series which later helped make Johns a major star. Ed had managed to catch it before the work was withdrawn from public view. Not fully aware of the undercurrents, I wrote an article about the political influences in the New York art world and used that work as an example of ways more established artists lend a hand to up-and-coming ones. I had meant it admiringly but it was taken just the opposite, complicated by the fact that the special relationship between Rauschenberg and Johns had ended and had not yet emerged from a sour phase and perhaps even more so by the fact that the small Johns painting had itself become more valuable than the work as a whole. Their dealer, Leo Castelli, read my article, telephoned and told me I was a “beetch” and forbid us to sell the slide of the work. So when I designed the catalogue called “The World’s First Pop Art Newspaper”, the slide was offered as a free special bonus. Although Leo forgave Ed and continued to cooperate with future photography sessions, he never forgave me. I thought then he was a silly little man and I still think so while giving him due credit for the absolutely brilliant job he did in helping make Rauschenberg, Johns, Lichtenstein and others into the giants of twentieth century art which they later became.

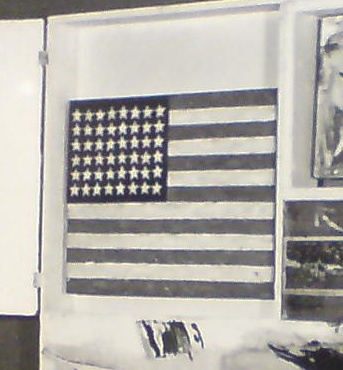

Ha, yow, not often you hear Leo Castelli called a silly little man, but not often you hear him calling someone a “beetch,” either. Good times. Also, it was not an all-white flag painting. Unless, of course, it was. The vintage photo I’ve been using [above] was taken by Rudy Burckhardt and dates from, I think, 1958. I didn’t realize Meneeley and Vanderburg had their own shot, too. But maybe there’s a Portable Gallery Bulletin slide floating around out there somewhere, and maybe it shows a white flag?

UPDATE: I can’t find any copies of Portable Gallery Bulletin for sale or in archives, never mind “The World’s First Pop Art Newspaper.” But Joel Finsel’s extensive bio/blog of Ed Meneeley has a photo of Ed’s own, lone copy, from early 1963, probably the next issue after Johns’ letter:

Hmm, Finsel also quotes the paper as offering “a free color slide of the Beatles!” which I guess one could get confused with Johns.

The Panther’s Tale: 014b [pantherhawaii.com]

Two Months.

Two months. I’d feign shock, but frankly, it’s been almost a year since I figured it out, and I’m only now posting it.

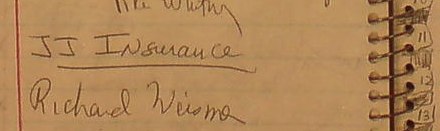

Last January, while going through the newly opened Castelli Gallery Collection at the Archives of American Art, I found some documents relating to the “loss” of the Jasper Johns Flag which had been inside Robert Rauschenberg’s 1955 combine, Short Circuit. [Remember, it was probably the first flag painting Johns made, and certainly the first one ever shown, by an easy three years. Complicated.]

There were notes about calling the NYPD 9th precinct and some preliminary paperwork for an insurance claim, all commencing on Tuesday, June 8, 1965. The insurance adjuster’s follow-up memo says a “theft” occurred, not just of the Johns, but of a similarly small sculpture edition by Roy Lichtenstein, on 6/6/1965, the previous Sunday. From the gallery’s storage facility on 1st Avenue. Obviously, they called right away, as soon as they found out.

Actually, no. I decided to track down the police report, only to run into a dead end. There were no reports of art thefts on or around the 8th at all. After a couple of fishing expeditions by mail, a kindly NYPD records officer took pity on me, and returned one of my $10 checks with a phone number on it. I called, explained what I was looking for, and she said she’d try to expand the search a bit when and if she could.

A few weeks later, just about a year ago now, I got a single page form with no details, just the basics of the police report. The date of the theft was listed as April 15th, nearly two months before Castelli called either the police or the insurance company.

Which means either the gallery didn’t realize the flag painting had been removed, or they did, and it spent two months trying to figure out what happened before giving up and filing an insurance claim.

It was the more interesting of the two.

Last winter, I reached Edward Meneeley, an artist and photographer who knew Johns and Rauschenberg well in the 1950s. Meneeley published the Portable Gallery Bulletin, a subscription newsletter/slide service which was used by schools, libraries and scholars to keep up with the latest New York shows. The Bulletin ran Johns’ only published comments on Short Circuit in 1962. Johns wrote a letter to the editor to refute the charge that Rauschenberg’s refusal to allow the Bulletin to distribute images of Short Circuit was due to art world “politics” and an attempt to rewrite history.

Meneeley recalled the hubbub surrounding the disappearance of the Johns Flag. Ed said, he had been photographing Ileana Sonnabend’s inventory/collection at the warehouse, and so he was there quite a bit during the spring and summer of 1965. He was asked a couple of times if he’d seen or knew anything, and so was “everyone else.” [I took this to mean people who were working around the galleries and the warehouse.] Which sounds like there was a general awareness that the flag painting had disappeared.

[Meneeley also said he thought Short Circuit had ended up in Sonnabend’s collection, but I asked Antonio Homem about this, and he confirmed that this had never been the case. Michael Crichton had originally written the work was in Castelli’s collection, but this was also not the case; the Rauschenberg Foundation told me it remained in Bob’s collection until he died.]

I’d thought that a two-month search for a missing Johns painting would leave a trace of some kind in the Castelli Archives, but if it’s there, I couldn’t find it. Once I had the April 15 date, I went through every page of the Gallery’s notebook and memo collection, as well as Castelli’s own daily calendar. There are lunches with RR, and finally, around June 11th, mentions of “JJ Insurance,” [little detail above] but otherwise, nothing.

There are plenty of mentions of insurance for all kinds of people in the archive materials, and other instances of JJ and RR claims–works were getting insured, damaged, assessed, and repaired all the time–so the mention above could be unrelated. But it does make me wonder if the claim for Johns’ Short Circuit flag painting was filed on behalf of Rauschenberg–or Johns? Does the practical fact that when it’s missing, Flag was being treated as an autonomous Johns painting affect how it should be seen art historically? In other words, can we thus assume it was a Johns painting, and not–or not merely–the raw material of a Rauschenberg combine?

Ed’s account also makes me curious about how widely known the 1965 theft–I guess we can call it that now–actually was. How many people were questioned? Did people gossip and speculate about it for a while? Who else knew? And was it registered as stolen with the appropriate industry databases? A year and a half, and I finally know the answer to that last question.

“Loss of Painting – American Flag – Jasper Johns”

A Brief Retelling Of The Story of Short Circuit, aka Construction With J.J. Flag

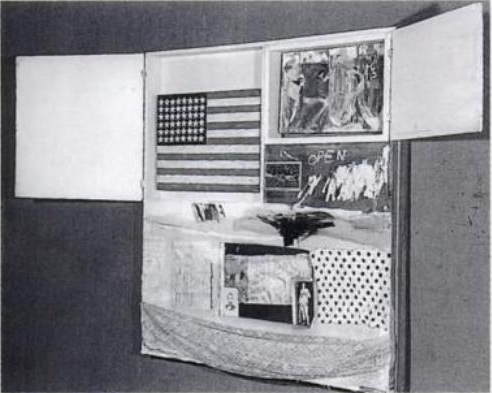

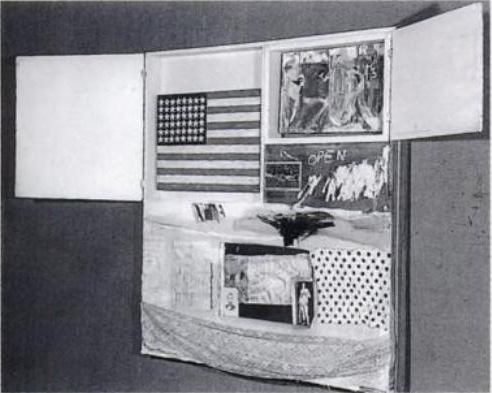

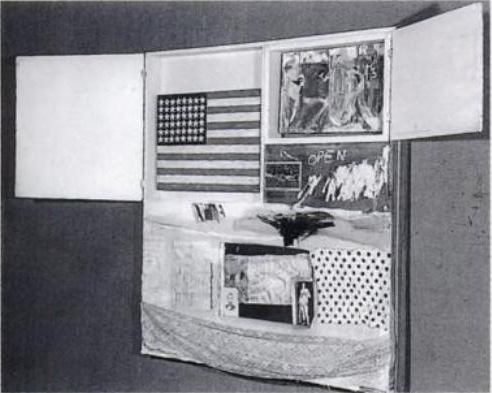

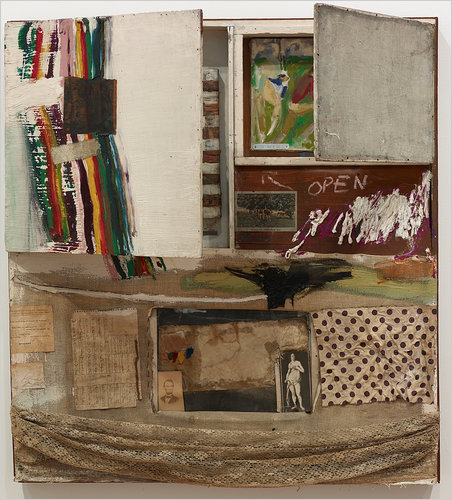

Construction with J.J. Flag, aka Short Circuit, 1955 photo by Rudy Burckhardt

You know what, it’s way past time to wrap up this missing Jasper Johns Flag caper. I’m going to get right to it.

But first, a quick review of the work’s history:

In 1955, three years before his debut solo show at Leo Castelli, Jasper Johns painted a small Flag which was incorporated into a Robert Rauschenberg combine, which was shown at the Stable Gallery annual Stable Show, which opened on April 26. The combine also included a painting by Rauschenberg’s ex-wife, Sue Weil. [Stan VanDerBeek and Ray Johnson were also invited by Bob to contribute a work, and several historical sources say it includes a Johnson collage, but the Art Institute of Chicago, which bought the piece last year, officially only cites the two painters. Though it was Rauschenberg’s stated intention to use the combine to get Johns’ and Weil’s works into the Stable Show, he was the only artist credited with participating.

Both paintings were enclosed behind cabinet doors, which could be opened, but which were originally exhibited closed. [In Paul Schimmel’s Combines show and at Gagosian, the doors were opened and, obviously, untouchable by the public, but I have heard from multiple people now that when Johns saw the Gagosian show, he confirmed that the doors were to be closed.]

The combine is now known as Short Circuit, but in Rauschenberg’s earliest works registry, it has the title, Construction with J.J. Flag. That entry referred to the work’s next known public appearance, in a show at Cornell University’s White Museum in April 1958, Collages and Constructions, curated by Alan Solomon. Johns was also included in the exhibition, which followed on the heels of both artists’ successful solo shows at Castelli that year. Even though Solomon went on to curate both Rauschenberg’s and Johns’ first museum shows at the Jewish Museum, and their participation in the US entry to the Venice Biennale in 1964, which Rauschenberg won, Solomon did not mention this show in their bios. And it was not included in Johns’ exhaustive chronology prepared for his MoMA retrospective.

In 1962, after Rauschenberg and Johns’ particularly bitter breakup, they came to a “solution of differences of opinion” about Short Circuit, which involved not selling the work, or publishing or exhibiting it again.

In his awesome 1977 Johns catalogue, Michael Crichton quoted Leo Castelli as saying that the Johns Flag had been stolen from Short Circuit at some point “before June 8, 1965.” [Crichton also wrote that Castelli acquired the painting, but the Rauschenberg Foundation told me that the artist never parted with the work.]

What’s not behind Door #1? Rauschenberg & Short Circuit in the 1967 Finch College “Art in Process” catalogue

The removal of the Johns Flag apparently freed up Rauschenberg to begin showing Short Circuit again, because he put it on a national tour of collage works organized by the Finch Museum in 1967. He said in the Finch catalogue that Elaine Sturtevant “is painting” a replica of Flag, but the artist’s photo blocks it from view. And the doors were nailed shut for the tour.

It’s unclear when Sturtevant actually painted her Johns Flag, but I’ve narrowed it down to some time between 1968 and 1971, when Rauschenberg’s one-time assistant Charles Yoder says he saw it in the studio. Short Circuit‘s next scheduled public appearance was in 1976, for Walter Hopps’ big Rauschenberg retrospective at the Smithsonian. Upon review of Hopps’ archive, it appears Short Circuit was originally included, then dropped from the show shortly before it opened. Burckhardt’s 1955 image was used in the catalogue. Rauschenberg wrote that he might repaint the flag himself because he “need[s] the theropy [sic].”

[One other thing I found in the Smithsonian archive: a memo from Hopps agreeing to cover Rauschenberg’s travel expenses to the DC opening, but refusing to pay for “his friend.”]

In 1980, Calvin Tomkins told the story of Short Circuit‘s missing Flag in his Rauschenberg biography, Off The Wall. He appears to have based his account on Crichton’s version, though he added a detail that could only have come from Castelli himself about an unnamed dealer bringing the Flag in for authentication. The notion that Castelli apparently let the painting walk back out of his gallery without a fuss is what triggered my interest in the first place. I mean, seriously, how could there be a Johns Flag painting on the loose, and no one does anything about it?

Anyway, Short Circuit was also not included in a 1985 show at the Hirshhorn on artist collaborations curated by Cynthia McCabe and David Shapiro. Shapiro later described the work as being in a sad state of repair and missing its Johns Flag. No mention of Sturtevant. According to the Rauschenberg Foundation, however, Short Circuit has never been damaged or repaired. It finally went on public view–the first time with the Sturtevant–in 2005 in Schimmel’s show at MoCA.

And that’s where we are.

So next week, I’ll finally get around to talking about what I’ve found out about the disappearance of the Flag, the aftermath, and its fate. And there’ll be a bit about how it alters Johns’ history–or at least it should–and then what it means for Rauschenberg’s, too. Stay tuned.

An admittedly imperfect way to see all the previous greg.org posts on the search for Johns’ Short Circuit flag painting

‘Bob Made It, But Jasper Made It Art.’

A couple of things that I still wonder about about Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing:

What did de Kooning think? The story of making it is always told by Rauschenberg, or from his side. Did de Kooning ever tell the story? Did he ever see the result? Or talk about it? Did anyone ever ask him about it? I’ve never found any reference at all.

When did Rauschenberg actually make it? The date’s all over the map. SFMOMA currently says it’s 1953. For a long time, it was dated 1953-55. James Meyer had it as 1951-2, but I don’t think I’ve seen anyone else put it that early. Even the extraordinary timeline in John Elderfield’s de Kooning retrospective catalogue has only the basics of Rauschenberg’s travel schedule and his account to go on [“Probably April or After,” it says, since April 1953 was when Rauschenberg returned from his European trip with Twombly.]

[UPDATENever mind. I got the EdKD dating ambiguity mixed up with Johns’ Flag, which has been variously dated between 1954 and ’56, whereas the date for EdKD has consistently been given as 1953 from its very earliest forays into the public view. Thanks to Sarah Roberts, research curator at SFMOMA, who took a moment from her multiyear project documenting Rauschenberg’s work, to point out my error.]

What did people at the time think? Who actually ever saw it? Even someone as early to the work as Leo Steinberg apparently only talked to Bob about it on the phone.

And what about Johns? Who knew about his involvement? What is up with that? For forty-plus years, while Rauschenberg claimed or let others write or publish that he came up with the title, and drew the hand-lettered label, Johns stayed silent about his role in the collaboration. But others surely knew, certainly in the early years when the work was taking shape.

Just before the holidays, I got in touch with Edward Meneeley, and artist and photographer who became friends with many artists and dealers in 1950s and 60s New York because he photographed their artwork. Meneeley created Portable Gallery, a subscription slide service that provided regular installments of art images to libraries, colleges, galleries, and collectors.

I found him because it was his monthly newsletter, Portable Gallery Bulletin, to which Jasper Johns wrote in 1962, explaining that it was artist’s prerogative, plus an agreement between himself and Rauschenberg, not “politics,” behind the refusal to let Portable Gallery publish and distribute slides of Short Circuit.

In a multi-chapter biography published online by Joel Finsel, Meneleey says that he was friends with both Johns and Rauschenberg in the late 1950s, and that he had an affair with the latter behind the former’s back. [He tells Finsel of Johns coming to his loft one morning looking for Rauschenberg, and inviting him in to talk about it, all the while Bob is hiding in Meneeley’s bedroom, eavesdropping on the conversation. Which sounds like a dick move to me, but there you go.]

Anyway, after talking to Meneeley for a while about Short Circuit–which he first saw in 1955, when it was first exhibited at the Stable Gallery–I asked him what people thought or said at the time about Erased de Kooning Drawing.

“Everyone at the Cedar Bar knew,” he told me, but they thought it was just a stunt, a joke. After finishing it, Rauschenberg didn’t do much with it or, as Meneeley put it, “he didn’t know what to do with it.” Until Jasper came along.

[Remember, Bob apparently acquired the original de Kooning sketch of a woman sometime after April 1953. He met and quickly became involved with Johns in the winter of 1954.]

In Meneeley’s recollection of the time, it was Jasper who basically saved Erased de Kooning Drawing from ending up as a barroom one-liner. He mounted it, gave it a title and a label, or really, a drawing of a label. “Bob made it,” Meneeley told me, “But Jasper made it art.”

Which is why I’m interested in hearing what people thought at the time it was made.

Johns On Rauschenberg: A Show In Tokyo

Fear not, I have not given up the search for the missing Jasper Johns Flag painting. The one which was in Robert Rauschenberg’s 1955 combine, Short Circuit, a combine which was originally shown with the title, Construction with J.J. Flag. The combine which was the subject of an unusual agreement between the two artists after their bitter 1962 breakup, that it would never be exhibited, reproduced or sold. Which technically did not happen, since the flag painting was taken out in 1965, and Rauschenberg put the piece, with the title, Short Circuit, on a national tour in 1967 as part of a collage group show organized by the Finch College Museum.

Which, point is, in looking for the flag, I keep finding more things I had never heard about Rauschenberg’s and Johns’ time together, a point at which they each were making hugely important, innovative work. And frequently, it seems, they were working on it together. His, mine, and ours.

For a few months now, I’ve been thinking about a letter Johns wrote to Leo Castelli, which I’d come across at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art. I’ve been kind of slow to mention it, partly because it just feels a little weird, like going through someone else’s mail. Which I guess it exactly what an archive is, but still. Also, I’ve been wary of reading too much into a single letter, or of over-interpreting a single statement.

But then I’m constantly struck by how frequently a particular phrase uttered in a single interview can get echoed across the writing about an artist, as if that one statement from decades earlier is somehow not just a snippet of a conversation, but a key to deep meaning. So this overdetermining tendency is not mine alone, and whatever, take it for what it’s worth.

In the spring and summer of 1964, while Johns traveled to Japan, he scouted out Kusuo Shimizu’s Minami Gallery for a future Rauschenberg exhibition sometime after the fall. Johns had some pretty specific suggestions about what kind of Rauschenbergs would work in the small, tight space:

I should think that smaller works as different as possible from one another would be good. Or if Bob is going to

use repeatedrepeat images in all the paintings, one work the size of a wall + several much smaller things. If Bob were willing, I think a good effect could be made by having one large painting + several smaller ones which used the same silk screen images but reduced in size. That is, two screens should be made of each image – one large + one small. The opposite would also work – a large painting with smaller images + smaller ptgs. with larger images.

It’s not that Johns is prescriptive, designing his ex-partner’s paintings at a distance. His language is very careful to couch the decisions as Rauschenberg’s to make. But Johns also has a marked fluency in Rauschenberg’s composition and process, and he seems comfortable discussing it, at least with their mutual friend and dealer.

Johns could discuss Rauschenberg’s silkscreening techniques in detail in 1964, even though Rauschenberg only began using silkscreens in 1962, the year the two finally broke up. [Crocus, done in the late summer/early fall of ’62, is one of the first/earliest silkscreen paintings.]

In any case, one more datapoint. As it turns out, Rauschenberg’s show at Minami never ended up happening. Fresh off his hyped and controversial grand prize win at the Venice Biennale, but while he was still also working as the stage manager for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s world tour, Rauschenberg visited Minami Gallery in the fall of 1964.

According to Hiroko Ikegami, Rauschenberg walked in, saw an exhibition of Sam Francis, [“who was still respected and popular” in Japan], and walked right out. Shimizu was offended, and canceled Rauschenberg’s show. Maybe before Rauschenberg canceled it himself, who knows? The Merce tour was a personal disaster for Rauschenberg, and a rift developed between him and Cage and Cunningham which took several years to heal.

Once You Start Looking For A Flag

In Memory of My Feelings – Frank O’Hara, Jasper Johns, 1961

I’m long overdue for updates on the search for the Jasper Johns Flag Painting that went missing from Robert Rauschenberg’s 1955 combine, Short Circuit. I’ll get to them when I get back home to my files.

Meanwhile, one by-product of searching for a flag: I start seeing them everywhere.

This little multiple by Gabriel Orozco is the first part of a series that doubles the number of rectangles on each sheet.

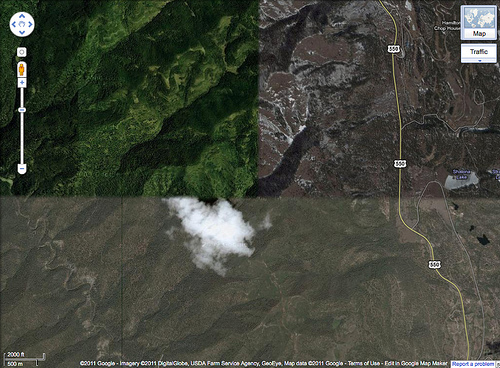

And on C-Monster, Carolina cropped this time-shifted collage she found on Google Maps into a very flaggish shape.

Hey-Ho, The Art Institute Bought Short Circuit

Short Circuit, Robert Rauschenberg, et al, via the estate/VAGA

I always [well, for a weekend or two last December, anyway] figured I’d find the original Jasper Johns flag painting that was inside Rauschenberg’s Short Circuit before the Combine was sold, so that it could be presented to its eventual owner in its original, art history-upending state.

Yeah, well. Turns out the missing flag was not a dealbreaker for the Art Institute of Chicago. Carol Vogel just released the news that James Cuno orchestrated the Museum’s purchase of Short Circuit, Sturtevant flag and all, from the estate, for an anonymously sourced price of $15 to $20 million.

In her piece, Vogel mentions the flag, and the Susan Weil painting, behind the cabinet doors. But then she says something I’ve never heard or seen anywhere: that though both were invited, neither Ray Johnson nor Stan VanDerBeek actually contributed pieces to the Combine VanDerBeek we knew, but Johnson?

I’d always understood that Johnson was in, and I’d assumed that the collage in the center of the lower half, with the Abe Lincoln and Venus postcard, was Johnson’s. If it blended so seamlessly with the rest of the Combine, and with the rest of Rauschenberg’s oeuvre, well, all the better. Johnson was famously sanguine about his collage work, and loved if his artist friends tweaked or reused it. Or so I’m told.

I like this reproduction of the piece, too, with the doors barely ajar. I’ve heard a story from a couple of people now, that when Johns went to Gagosian to see the show, he mentioned that the doors on Short Circuit were supposed to be closed. This image kind of finesses the door, concealing just enough so that the first thing you say when you see the piece is, “Holy smokes, that’s a Jasper Johns flag three years before he showed it anywhere!”

Prime Rauschenberg at Chicago Art Institute [nyt]

Previously: Until I get some tags, this is how you find all the Short Circuit-related posts around here

‘A Sort Of Collaboration’

Erased de Kooning Drawing as of 1999 at SFMOMA

When we last left Erased de Kooning Drawing, the late, great Leo Steinberg had finally told his story about getting Rauschenberg on the phone in 1957 in order to sort the damn thing out. Steinberg’s conclusion was that, far from a “Neo-Dada” prank or Oedipal negation, Rauschenberg had offered de Kooning “a sort of collaboration” of erasure. The plausibility of this interpretation was inspired by the equally collaborative combine painting of the same period, Short Circuit.

Erased de Kooning Drawing, without present matboard, c. 1970, via Emile de Antonio’s Painters Painting

So to recap quickly: EdKD is a collaborative work. In which erasure-as-drawing is the subject, or the strategy. Each artist with his different markmaking method. And it is inscribed, labeled, by hand, with a flatly descriptive title and claim of authorship. And though it had been unmatted at some point [above] rendering the inscription and the drawing as one collaged work, it was matted in a way that obscured this unity, and it was [eventually] presented as a framed, presented object. A conceptual work, realized. A concept of a drawing erased. Hold all that in your head. Am I missing anything?

Erased de Kooning Drawing, detail, c. 1970, via Painters Painting

Anything besides the small detail that the inscription, the text, the third instantiation of the concept, the generative inverse of the erased drawing itself, was made by Jasper Johns?

For the crucial period of EdKD‘s uptake into the art world’s discourse, Rauschenberg had always claimed that he had written the inscription. That he’d “signed” it. That’s what he told Emile de Antonio on top of that ladder. That’s the only way anyone talked about it. But it is not true.

Vincent Katz has made one of the rare references to the importance of the work’s collaborative creation in Tate Magazine in 2006. But others credit Calvin Tomkins with breaking the news of Johns’ involvement in EdKD in his 2005 New Yorker profile of Rauschenberg:

Johns gave Rauschenberg the title for “Erased de Kooning Drawing,” which came into being in 1953, when Rauschenberg persuaded de Kooning to give him a drawing which he would then erase, to see whether a work of art could be created by the technique of erasure; Johns also did the precise lettering for the title, on the framed matte below the very faint, wraithlike ghost of the erased image.

The title, of course, is not on the matte, but under it. It was originally of a piece with the drawing, until the matte separated it, demoted it, even. Which may intensify the implications of difference between pre- and post-matted drawing.

[Tomkins does not identify the source of his revelation about Johns’ involvement, even though he wrote in the same piece that “Johns recently told Joachim Pissarro, a curator at MoMA, that he thought the term ‘combine’ had been his suggestion.” The latter was a memory Rauschenberg apparently did not share.]

Tomkins may have been the first to publish it, but claim of Johns’ collaboration was first made at least six years earlier, by a seemingly unlikely source: Robert Rauschenberg.

In a 1999 video interview about the newly acquired EdKD, Rauschenberg told SFMOMA curators,

So when I titled it, it was very difficult to figure out exactly how to phrase this.

And, uh, Jasper Johns was living upstairs, so I asked him to, to do, the uh, the writing.

And they say you never get to know your neighbors in New York. Sometimes you make historic works of art together with them.

Except that on Pearl Street, as Castelli famously told it, Johns was downstairs. And Rauschenberg was upstairs, in the loft vacated in the summer of 1955 by Rachel Rosenthal, who had found the building in the Spring of 1954. Rauschenberg was certainly around–and living around the corner–before then. They’d met early in the winter of 1954, began and he and Johns had already created and shown Short Circuit by then. So either Rauschenberg was referring to a time before they moved in together, Or Johns didn’t add his pieces to the drawing before mid-1955. Either way, it sounds like the drawing, to use Tomkins’ odd phrasing, actually “came into being” after 1953, the date Johns wrote on it.

Part 1: ‘FRAME IS PART OF DRAWING’

Part 2: Erasers Erasing in Painters Painting

Part 3: Norman Mailer on Erased de Kooning and other ‘hopeless’ and ‘diminished’ art

Parts 4&5: Leo Steinberg on EdKD and how it’s a collaboration

Part 6: A 3-Way Collaboration, that is, with Jasper Johns. Oh, that’s this post. Just one more, I think.

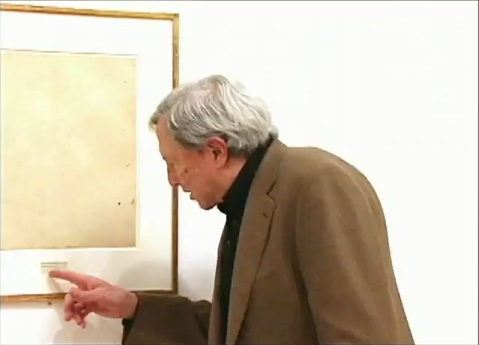

Encounters With Erased de Kooning Drawing

You know what, it’s the weekend. We can have two long Leo Steinberg-related posts at once. Read’em on the NetJets to Basel.

Though he mentioned it in his most important piece of writing, which was also the most important piece of writing on Rauschenberg, it’s not entirely clear whether Leo Steinberg had actually seen Erased de Kooning Drawing when he wrote “Other Criteria.”

Though he mentioned it in his most important piece of writing, which was also the most important piece of writing on Rauschenberg, it’s not entirely clear whether Leo Steinberg had actually seen Erased de Kooning Drawing when he wrote “Other Criteria.”

And as he tells the story in his awesome 2000 book, Encounters With Rauschenberg – A Lavishly Illustrated Lecture, Steinberg makes not seeing it the point. I’m really tempted to include all seven pages of EdKD from the 85-page book–the text was published straight from his lectures for the 1997-8 Rauschenberg retrospective at the Guggenheim and Menil, and it really sounds just like him. [I met Steinberg in 1991 when the delightfully friendly woman I was sitting next to for his Picasso lecture series at Rice University introduced us; she turned out to be his host, Dominique de Menil. Life-changing, &c, &c. but not right now.]

But I won’t. Even though it’s out of print and expensive. It really should be a PDF now. Anyway.

Steinberg’s take on EdKD is useful here because he was watching Rauschenberg’s career and involved in its critical dialogue almost from the very beginning; he’s about as well-informed or as thoughtful an audience voice as Rauschenberg could find in the 1950s and 60s. And so his reaction seems like a good proxy for the best perspective possible of the time. And it sounds like, though he felt he had to address it, and though he could argue for its critical or conceptual significance, Steinberg didn’t really like Erased de Kooning Drawing very much. It bugged him. He even apologized to his lecture audience for spending “so much time on a negative entity” and a “one-time exploit.” But but!

The lead-in for his story about first encountering EdKD was, interestingly enough, an anecdote from 1961 and Rauschenberg and Johns, about artists putting personal content into their work, and denying it, and then eventually ‘fessing up, and so about not quite trusting what artists themselves said:

That experience confirmed me in a guiding principle of critical conduct: “If you want the truth about a work of art, be sure always to get your data from the horse’s mouth, bearing in mind that the artist is the one selling the horse.”

And did I abide by my principle? I should say not! My longest conversation with Rauschenberg occurred c. 1957, when I first heard about something outrageous he’d done some years before. And rather than going after the outrage–the horse, as it were–I called the trader.

[uh, don’t want to spoil the story arc, but isn’t not ignoring a lesson in 1957 that stems from looking back from the 80s to a 1961 conversation putting the horse before the trader? Just sayin’. -ed.]

The work in question was Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing of 1953. The piece had not been exhibited; you heard of it by word of mouth. I did, and it gave me no peace. Because the destruction of works of art terrifies.

See, now this is news right there: not exhibited before, word of mouth, a piece you know and worry about without seeing.

How could Bob have done it; and why? The work is often, and to this day, referred to as “a Neo-Dada gesture,” but that’s just a way of casting it from your thought. Obvious alternatives to Neo-Dada suggested themselves at once. An Oedipal gesture? Young Rauschenberg killing the father figure? Well, maybe.

But wasn’t it also a taunting of the art market?–an artist’s mockery of the values now driving the commerce in modern art?

This would put paid, so to speak, to Norman Mailer’s complaint that Bob was erasing to play the market. Steinberg tells how everyone was very aware/shocked/jealous/disturbed when a de Kooning finally sold for $10,000. And Rauschenberg was the one, don’t forget, who got the angriest at Robert Scull for his market-making auction some years later. But all these seemingly contradictory interpretations, Steinberg pointed out, were just assumptions from afar.

So I picked up the phone and called the horse trader himself. And we talked for well over an hour. Occasionally, thereafter, I considered writing up what I remembered of our talk, but then Calvin Tomkins discussed the Erased de Kooning Drawing in his Rauschenberg profile in The New Yorker, and he did it so well that I thought, “Good, that’s one less thing I have to write.” But I don’t mind talking about it and recalling whatever I can of that phone conversation.

On the first question of why, Rauschenberg gave an explanation similar to the one he’d told Emile de Antonio: he was interested in drawing with an eraser “as a graphic, or anti-graphic element,” and found that erasing his own work was unsatisfying.

As for why de Kooning and not some other pre-existing work of art, Steinberg examines and largely discounts the Oedipal explanation, and instead suggests that Rauschenberg recognized or claimed a kindred spirit, that erasure as a technique was central to de Kooning’s own practice. And yes, this section I’m obviously going to quote at length:

There is another reason, I think, why Bob lit on de Kooning. I live with a de Kooning drawing from the early 1950s–it’s of a seated woman, frontal, legs crossed [below]. The face was drawn, then erased to leave a wide, gray, atmospheric smudge; and then drawn again.

Willem de Kooning, Woman in a Rowboat, 1953

And here is Tom Hess’ account of Bill de Kooning’s working method. I’d like to read you a paragraph from Tom’s book Willem de Kooning Drawings (1972), and I’m encouraged to do this by the example of Rauschenberg’s Short Circuit combine, which, you remember, brought in some of Bob’s friends piggyback. Tom Hess was a friend; hear him describe de Kooning’s habit of draftsmanship.I remember watching de Kooning begin a drawing, in 1951, sitting idly by a window, the pad on his knee.He used an ordinary pencil, the point sharpened with a knife to expose the maximum of lead but still strong enough to withstand pressure. He made a few strokes, then almost instinctively, it seemed to me, turned the pencil around and began to go over the graphite marks with the eraser. Not to rubout the lines, but to move them, push them across the paper, turn them into planes…De Kooning’s line–the essence of drawing–is always under attack. It is smeared across the paper, pushed into widening shapes, kept away from the expression of an edge…the mutually exclusive concepts of line and plane are held in tension. It is the characteristic open de Kooning situation…in which thesis and antithesis are both pushed to their fullest statement, and then allowed to exist together…

This much Tom Hess.

In view of such working procedure, one might toy with this further reason why Rauschenberg’s partner in the affair had to be de Kooning, rather than Rembrandt or Andrew Wyeth. De Kooning was the one who belabored his drawings with an eraser. Bob was proposing a sort of collaboration, offering–without having to draw like the master–to supply the finishing touch (read coup de grace)

I could just go on and on. Steinberg noticed that, despite declaring his early love for drawing, Rauschenberg seems to have pretty much stopped drawing after the early 50s, Erased de Kooning Drawing was really about erasing drawing itself.

And since he brought it up, and in the context of collaboration, too, maybe that makes Short Circuit, which includes two paintings by his partner and ex-wife, a way to wrangle painting into its place, too: subsumed behind closed doors. It’s an admittedly rough analogy, but then, I only just thought of it.

In any case, Steinberg’s collaborative interpretation of Erased de Kooning Drawing is worth holding onto. On with the story:

Meanwhile, Bob and I are still on the phone. And Bob says, “This thing really works on you, doesn’t it?”…Finally, I asked, “Look, we’ve now been talking about this thing for over an hour, and I haven’t even seen it. Would it make any difference if I did?” He said, “Probably not.” And that’s when it dawned on me–it’s easy-come now, but the thought had its freshness once–I suddenly understood that the fruit of an artist’s work need not be an object. It could be an action, something once done, but so unforgettably done, that it’s never done with–a satellite orbiting in your consciousness, like the perfect crime or a beau geste.

Since then, I’ve seen the Erased de Kooning Drawing several times, and find it ever less interesting to look at. But the decision behind it never ceases to fascinate and expand.

It now seems to me that Rauschenberg has repaid de Kooning’s gift to him. For though we all know de Kooning to have been a great draftsman, I can think of no single de Kooning drawing that is famous the way some of his paintings are, except the one Bob erased.

‘One Of The First Works That They Made After Becoming A Couple’

In Memory of My Feelings – Frank O’Hara, 1961, Art Institute of Chicago

I’ve had a jpg of Jasper Johns’ 1961 painting, In Memory of My Feelings – Frank O’Hara on my desktop for months now. It was one of the most important works in the National Portrait Gallery’s “Hide/Seek” exhibition, and I took the chance to study it up close several times throughout the run of the show.

I have also been a little wary to write much about it, and its seemingly powerful resonance with Johns’ Short Circuit flag, partly because I was unsure of how much to read in, and how relevant or not the associations I was seeing really were.

In Memory of My Feelings definitely relates to the other, larger Flag–at 40×60 vs 42×60, it’s nearly identical in size. But unlike the 1955 Flag, or any other flags, it’s made of two canvases hinged together. Hinges, functional and not, are just one unexamined element that appears in both Johns’ and Rauschenberg’s early work. [Light bulbs are another. Maps, just barely.]

When In Memory is discussed, the somber, grey tones come first. Then there’s Johns’ stenciled inclusion of the words “dead man” next to his own name on the bottom. And the overpainted skull that you can barely make out in the upper right quadrant somewhere. And that’s it, and then the Frank O’Hara reference takes over, and the irony that Frank O’Hara would die five years after this was made–as if this had anything to do with the painting, or Johns’ painting of it.

And so I wondered why I couldn’t find anyone talking about what IS clearly visible through the overpainting in the lower right section [detail above], which is a series of vertical red and white stripes. A flag. Or maybe two. Photos weren’t allowed in NPG exhibition, and I can’t remember now. But there is at least one flag painting under there.

One person who does talk about In Memory of My Feelings, though, is “Hide/Seek” co-curator Jonathan Katz. In a gallery talk video, Katz talks about putting Johns’ and Rauschenberg’s works side by side to show it for the first time in the context of their relationship, and particularly their breakup.

Katz talks matter-of-factly about these artists’ relationship and collaboration in a way that no curator ever has. And keeping the bitterness of the breakup in mind certainly brings a lot of content to the fore in Johns’ painting. It feels especially necessary for understanding why Johns might have chosen to reference this poet and this poem. [Spoiler: it’s about dealing with the despair of a breakup.]

But Katz, whose delivery is slick and precise, not a word out of place, drops what I think is a bombshell? And just keeps on going:

When [Johns] and Rauschenberg met, one of the first works that they made after becoming a couple, was the famous–even iconic–Jasper Johns American Flag painting. This is a picture of that flag, in grey, reversed. The obverse of the picture that they made when they got together.

In one sense, it’s obvious, and in another, it’s ridiculous. Or at least unheard-of. Yes, definitely unheard-of. Katz is proposing, in passing, fundamental changes to the understanding of bodies of work, practices, and histories of two of the most important artists of the last 100 years.

This is the compelling thing for me about Short Circuit, an early 1955 Rauschenberg combine with a Jasper Johns flag behind a hinged door. A work which was originally/also titled Construct with J.J. Flag, and which was exhibited by Alan Solomon under both their names in 1958. It makes the otherwise incredible, even shocking assertion that Johns and Rauschenberg collaborated and made some of their most important work together seem perfectly obvious.

Mister Rauschenberg’s Neighborhood

Christie’s is selling The Tower, a 1957 combine by Robert Rauschenberg which Victor and Sally Ganz bought from Betty Parsons in 1976. The work is a double portrait assembled from found, painted objects and light bulbs, and was originally part of the set for a Paul Taylor Dance Company production based on the myth of Adonis. The costumes for the production were designed by Rauschenberg’s partner Jasper Johns.

Christie’s is selling The Tower, a 1957 combine by Robert Rauschenberg which Victor and Sally Ganz bought from Betty Parsons in 1976. The work is a double portrait assembled from found, painted objects and light bulbs, and was originally part of the set for a Paul Taylor Dance Company production based on the myth of Adonis. The costumes for the production were designed by Rauschenberg’s partner Jasper Johns.

Did I say partner? I guess I meant neighbor. Here’s Christie’s quoting Paul Schimmel from his 2005 Combines exhibition catalogue:

While Rauschenberg’s work does respond to the painterly traditions of the 1950s, it does so in a manner that isolates the act of painting from the complete composition. For him, painting became a thing, an object treated similarly to Assemblage in which elements were organized on a non-hierarchical surface. Rauschenberg took aspects of Picasso and the Cubist collage, Kurt Schwitters, and the Surrealism of Joseph Cornell and created a three-dimensional, collage-based art. Together with Jasper Johns, Rauschenberg defined the American art of the 1950s; Pop art would have been inconceivable without their respective breakthroughs. Incidentally, many of their most important advancements were devised when they were most closely associated, living as neighbors, during the second half of the 1950s-the period during which The Tower (1957) was created.

[emphasis added for salient points regarding Short Circuit and for WTF, respective? Incidentally? Neighbors??, respectively.]

Schimmel goes on to note that the appearance here of a broom “anticipates Jasper Johns’s use of the broom in Fool’s House (1962), at a time when they were no longer neighbors.” Yet while he notes that “Lights and bulbs,” one of the defining elements of The Tower, “recur in numerous works”–of Rauschenberg–the fact that just months later, while they were still, uh, neighborly, Johns chose a light bulb as the subject of his first sculpture goes completely unmentioned.

Light Bulb (I), 1958, Jasper Johns, image: mcasd.org

Here is Post-War & Contemporary Deputy Co-Chair Laura Paulson in a gallery talk video,

The Tower is very autobiographical, using found imagery, found objects that would give you clues to aspects of Rauschenberg’s life. Rauschenberg was a gregarious, outgoing, very generous person, but he spoke often in sort of cryptic, very defined ways. And in Tower you have this sort of personage, which to me is just so perfectly Rauschenberg, you really feel this inside/outside aspect of it. And to me, that really defines how his art was: very autobiographical, giving you clues, but not necessarily the full story.

You don’t say.

It’s a little bit funny. One reason I’ve stayed so interested in Short Circuit has been the implications of finding the original Jasper Johns Flag on the creation myth of Flag itself. Because really, what would it mean if Johns’ first flag painting was actually shown inside his boyfriend’s combine? And he didn’t even get credited for it? What if Johns’ idea to paint the flag came from the same place as his idea to paint the map, Rauschenberg?

But what if it goes both ways? The Tower, Schimmel writes, dates from “the middle of Rauschenberg’s Combine period, which extends roughly from 1954 to 1962.” Which is, incidentally, also the period Johns and Rauschenberg were a couple. What if combines came from Johns? Or silk screening?

Or maybe it’s not so simplistic or binary. Maybe “their respective breakthroughs” were collaborative? Maybe they talked through and worked through “their most important advancements” together? How does Target with Plaster Casts relate to the combines of 1955? Or how do the combines relate to Johns’ object-laden paintings of the post-breakup era? What do the famously autobiographical, emotionally-charged-yet-obdurate works of these two artists reveal about each other, their life together, their production, and the culture in which they lived?

For three generations now, the art and art history worlds have been arguing for the separation of these two artists and the distinct, unknowable power of their “respective” achievements. Some day maybe we can tell the full story.

Lot 28, The Tower, 1957, est. $12,000,000-18,000,000 [christies.com]

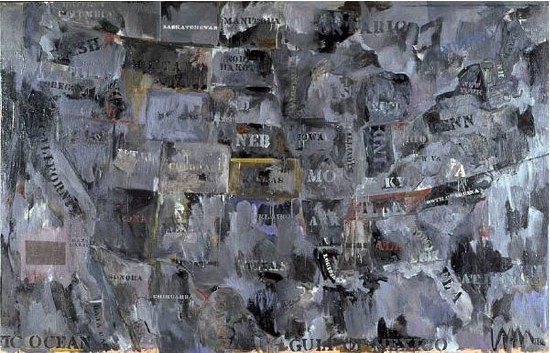

The Orgies Of Art History

Map, 1962, Jasper Johns, via moca.org

For her contribution to the Jasper Johns Gray (2007) catalogue, Barbara Rose writes about the history and significance of Map, 1962, the artist’s first big, gray masterpiece. Johns made it to raise money for his new Foundation for Contemporary Arts, which was founded to stage some performances of Merce Cunningham. Marcia Weisman bought it out of Johns’ studio and ended up leaving it to MoCA.

Rose suggests that Johns’ Map paintings are akin to battlefield maps, and that the gray one, in fact, resonates with a particular Civil War battle, the Battle of Antietam. She cites Johns’ own South Carolina upbringing, the centennial commemoration of the Civil War that was in the news in 1960-2, and a series of paintings by Frank Stella which drew some of their titles from Civil War battlefields. [Rose was married to Stella at the time, of course, and also refers to one diptych from the series titled Jasper’s Dilemma.] Also, Rose writes, “The difficult realities of Johns’s personal life coincide with the idea that this map pictures a battlefield.”

After recounting some formalist skirmishes with General Clement Greenberg’s troops, Rose zooms in on the surface of the painting and on some of the collaged elements in Map that Johns intentionally left visible:

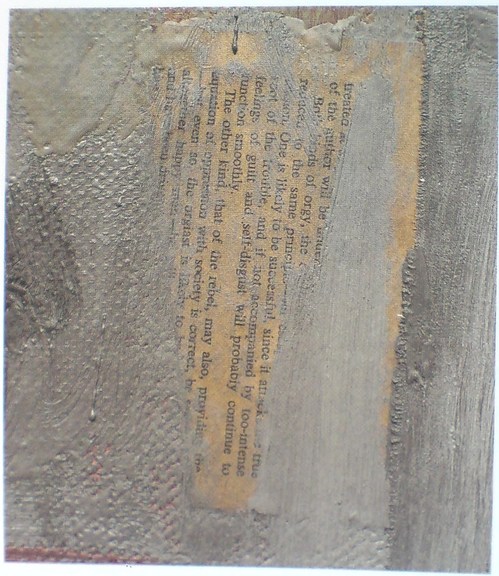

Topographically, the hills, ridges, and ravines of Johns’s gray Map suggest geological strata bursting. Paint washes over the surface like sea spume or waves eroding coastlines. Known borders are changed or blurred. This transgression of boundaries is a physical fact of art historical as well as personal significance. The surface is scarred and scraped in areas so that the printed matter sealed into it with adhesive encaustic is visible. The most tantalizing fragment is not newsprint but part of a page, probably ripped from a paperback book Johns had in his studio. One can make out the words “intense feelings of guilt and self-disgust,” as well as “rebel” and “orgiast.” These chosen and deliberately revealed phrases participate in Johns’s game of peekaboo, which he plays with his audience, much as a stripper suggests that more will be revealed with each succeeding fan flutter.

Map detail, via Jasper Johns Gray

Lots of interesting stuff, but I am most fascinated by the overall strategy Rose adopts, of floating the connection to “the difficult realities of Johns’s personal life,” and then going both wide and deep about everything but.