I’ve been focusing so much time on Johns, I fear I’ve been neglecting Johnson. But I wonder if he’s alright with that. Maybe Ray Johnson’s collage blends so seamlessly into Rauschenberg’s Short Circuit because collaboration, transformation, and subsumption were so central to Johnson’s own highly advanced, collaging practice. It’s enough to make me wonder what, if any, influence Johnson had on Rauschenberg during those early Black Mountain and combine days. Hopefully, there are theses on this already, or at least already in the works.

Meanwhile, I’ve had Johnson’s remarkable 1951 painting, Calm Center, open on my desktop for a couple of weeks now. It’s just beautiful. And the seriality, the grid, the geometry, the pixels, in 1951! I mean, wow. This what he dropped to start his correspondence and pop? Johnson could have been any major artist he wanted to be, and I think he was.

I’m gonna rewatch How To Draw A Bunny right now.

Previously: Ray Johnson on greg.org

Tag: short circuit

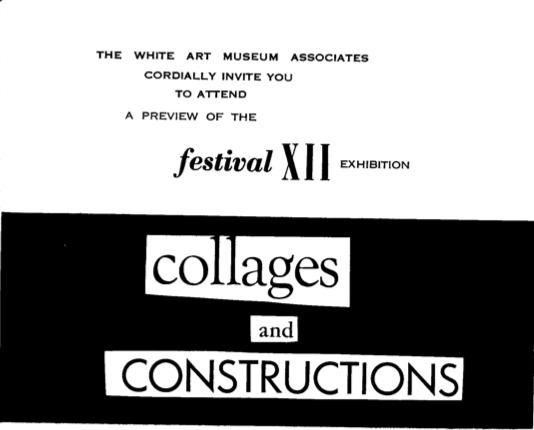

Collages And Constructions, 1958

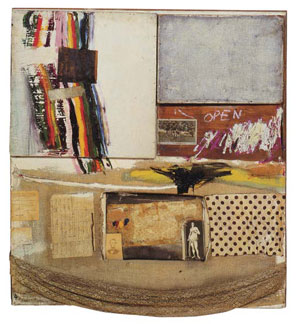

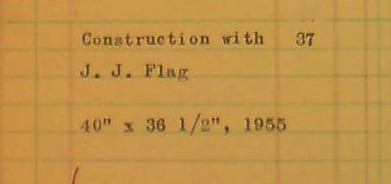

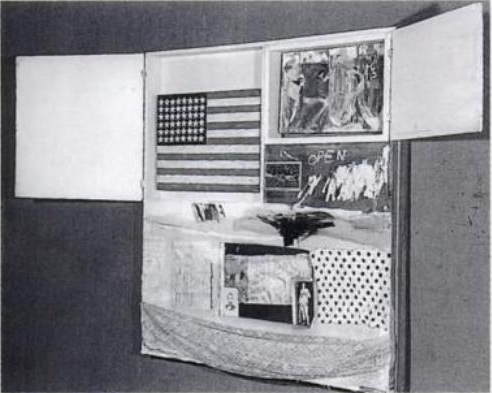

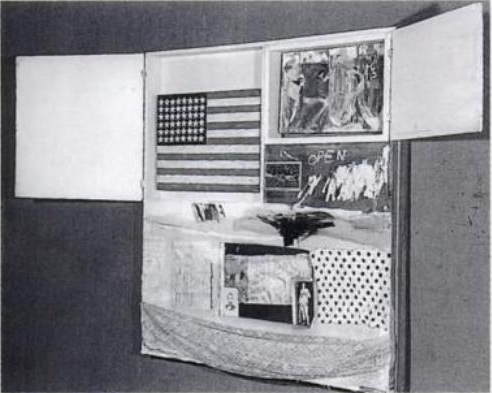

I think Robert Rauschenberg’s Short Circuit was exhibited only twice in its original state: once in the Spring of 1955, in the Stable Gallery annual exhibition for which it was created, and once at the White Art Museum at Cornell University, in 1958.

So far, I haven’t found a mention of the title, Short Circuit before at least 1967, when Rauschenberg exhibited the combine [with the doors nailed shut, to hide the space where the Johns Flag had been, but also hiding his ex-wife Susan Weil’s painting in the process] in a Finch College Museum traveling exhibition.

As mentioned here, Rauschenberg’s earliest registry [which is in the Castelli Gallery archives at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art] has the work listed as Construction with Jasper Johns Flag. Which would be an unusual title for the work to be shown with at Stable Gallery, where the whole point was for Bob to smuggle in works by Weil and Ray Johnson as well as Johns.

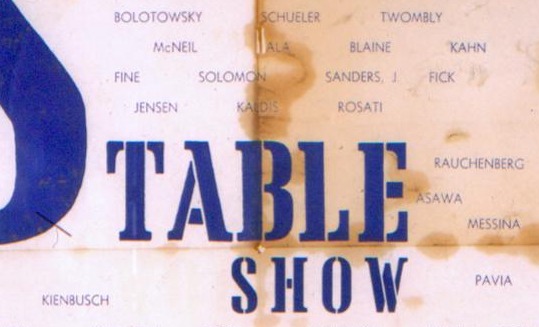

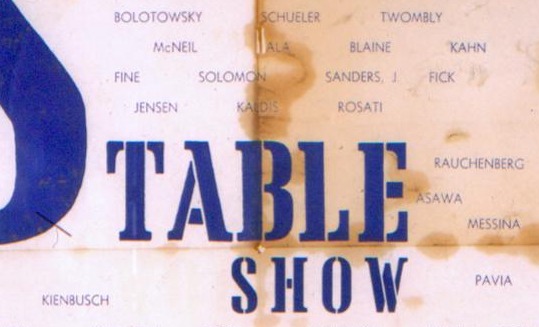

But thanks to the help of Liz Emrich, curatorial assistant at Cornell’s Johnson Museum, we now know more about the 1958 exhibition, which was curated by Alan Solomon. And though there’s no works list, the list of participating artists makes me wonder if this combine was exhibited as a collaboration, or as a joint/hybrid work.

The show was titled “Collages and Constructions,” and it ran as part of the Festival of Contemporary Arts. Paul Schimmel’s Combines catalogue lists the dates for the show as running from March 13 to May 20th, but it seems that information is from the artist’s registry, and probably pertains to loans of the work. The press release says it ran from April 10 to May 6, 1958. But yet there’s also an invite to hear Rauschenberg speak on April 8, fresh off his Castelli debut. So maybe the show was open sooner.

Anyway, Short Circuit, or Construction with Jasper Johns Flag, as the artist called it, was one of at least three Rauschenbergs in Solomon’s show. According to Schimmel’s Combines, the other two were Gloria and Small Rebus, [both 1956].

The show also included works by: Alberto Burri, Joseph Cornell, Jean Follett, Sue Fuller, Ilse Getz, Robert Goodnough, Grace Hartigan, John Hultberg, Jasper Johns, Allan Kaprow, Alfred Leslie, Corrado Marca-Relli, Anne Ryan, Richard Stankiewicz, “and others.” The press release mentions everyone but Getz and Follett. No word on who those “others” might have been.

I was surprised to find Solomon left his own 1958 show out of Rauschenberg’s exhibition history in his 1963 catalogue. I was not as surprised, though, to see the show not mentioned at all in MoMA’s otherwise definitive-seeming exhibition history for Johns.

Friends Of Alan Solomon

Johns, Flag: “American artist Jasper Johns has produced a distinguished body of work dealing with themes of perception and identity since the mid-1950s.” –whitehouse.gov

I’ve been trying to get a better sense of the first decade for Rauschenberg’s Short Circuit, from the mid-1950s, when it was made and first shown, until 1965, when the Jasper Johns Flag was removed from the work which had originally been titled, Construction with Jasper Johns Flag. It happens to be the time when both artists’ careers skyrocketed; when their intense personal relationship flourished, then fell apart; and when they were creating arguably their most significant works. And one of the people who was there for all of it was Alan Solomon.

Solomon was a curator and friend of Leo Castelli; he showed both Johns and Rauschenberg–including Short Circuit–in March 1958 at Cornell University’s White Art Museum. More on that later.

After he moved from Ithaca to the big city to run the Jewish Museum, Solomon gave Rauschenberg his first solo museum show in 1963. And he did the same for Johns in 1964. And he curated both artists into the US exhibition at the Venice Biennale in 1964, which erupted into controversy when Rauschenberg won. [The controversy was nominally about the eligibility of the US show, which was mostly installed in the former American consulate next to the Guggenheim, and only partly in the US Pavilion. But basically, it boiled down to Europeans being pissed at the American bad boy winning. I think.]

Long story short, Solomon was a key, early supporter of both artists’ work, and throughout the 1960s, he regularly made the argument that Pop, which he was also instrumental in promoting, was born directly from the work of this pair of “germinal artists” Rauschenberg and Johns.

Which is funny, because reading through Solomon’s texts, speeches, and interviews, you wouldn’t know Johns and Rauschenberg were even dating, much less spawning heirs. Though he showed the collaborative combine painting itself in 1958, Short Circuit is completely absent from Solomon’s exhibitions, texts, and interviews in 1963, ’64, and ’66.

What is present, in catalogue essays for both artists, is Solomon’s repeated and unequivocal rejection of the personal, the emotional, the biographical, the expressive, almost any type of subject or subjectivity at all, in fact, in their revolutionary work.

Looking back at the critical content closet Solomon constructs around these artists and their work–constructed with, you have to assume, their blessing and even active involvement–it’s tempting to take everything he says and simply invert it, and feel like you’re getting a clearer picture of what’s going on.

When Solomon writes of the importance of “other possibilities” to appreciating Johns’ Flags, while explicitly excluding the possibility of any personal associations, it almost seems like an invitation, a demand to consider them in an autobiographical light, as a kind of silent self-portrait. Which becomes very complex very quickly when the germinal Short Circuit re-enters the mix.

But I still have to figure out how, what, or whether to write about that head-on.

For right now, here are a couple of excerpts from Solomon’s catalogues for each artist. Johns first:

Which Flag Story? Which One Do You Know?

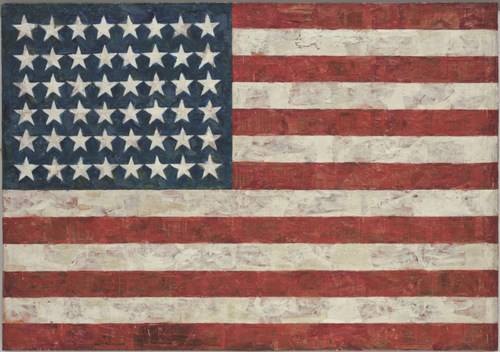

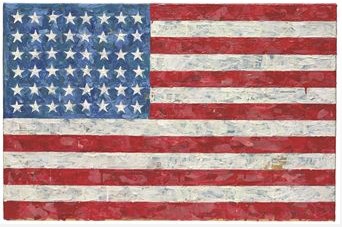

Flag, 1954-55, via moma

The creation myth for Jasper Johns’ Flag is well-known, and well-told. Like Leo Castelli’s story of discovering Johns’ groundbreaking oeuvre, fully formed, while he and Rauschenberg were raiding the icebox, and how Johns’ first show in 1958 got on magazine covers, sold out to MoMA, destroyed Abstract Expressionism and ushered in Pop Art. MoMA’s wall text for Flag [which Alfred H. Barr had Philip Johnson purchase from that show] begins:

“One night I dreamed that I painted a large American flag,” Johns said, “and the next morning I got up and I went out and bought the materials to begin it.”

It came in a dream. It’s a protean story, quintessentially American, slightly romantic, and beyond the reach of anyone but [Freudians, Jungians, and] the artist himself. And that’s the key: because unfalsifiable is not the same thing as definitive, or even true.

In the opening of her 1975 dissertation, published in 1985 as Jasper Johns’ Paintings and Sculptures, 1954-1974, Roberta Bernstein takes a researcher’s step back:

When asked about the sources of Flag, 1954-55, Johns answers that he dreamt one night of painting a large American flag and then proceeded to do so. He has said this several times and will offer no other explanation for the appearance of this remarkable painting.

In the footnotes, Bernstein cites Alan R. Solomon’s catalogue for Johns’ 1964 Jewish Museum show, as well as several personal retellings.

But check out this transcript of Solomon interviewing Johns in 1966 for National Educational Television’s USA Artists Series. Then tell me if it doesn’t sound like there could be another story–or several–for the origin of the flags?

‘Much To See But Not Much Shown’

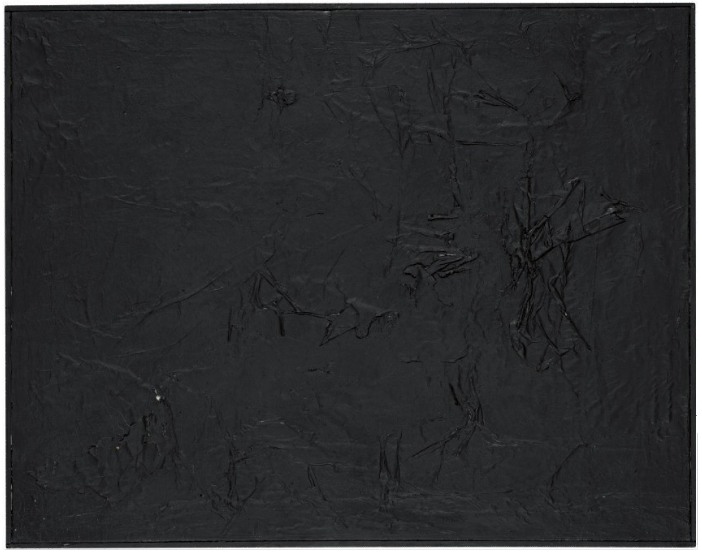

I took the kid to see Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s Legacy Tour the other night. And as I’m reading up on the funding of the Trust that will oversee Merce’s choreography after the company disbands, I found a mention of Robert Rauschenberg’s No. 1, a 1951 black painting which was sold after Merce’s death in 2009. Fascinating and, as I look at Bob’s unusual collaborative combine from a few years later, newly complex.

No. 1 was a gift to John Cage, which sounds simpler than it was. Cage had seen Rauschenberg’s first one-man show at Betty Parson’s Gallery in May 1951, and had asked for a work. As Christie’s catalogue entry put it, “The price, he said, was unimportant as he couldn’t pay anything. It was in this way and in this form that this painting first entered Cage’s possession.” As Carol Vogel put it in writing about the auction, Rauschenberg didn’t give the painting to Cage until “some years later.” But that can’t be right, as we’ll see below.

What No. 1 looked like at that point, no one is able to recall. Whatever it was, Rauschenberg had actually painted it onto a painting by his wife, Susan Weil. Vogel notes that Weil’s signature, and the date, 1951, are on the back of the painting, as is Rauschenberg’s. [Christie’s catalogue description only mentions the latter.]

This may have been an economic move as much as, if not more than, a collaborative or negating one. At the time, Rauschenberg and Weil were broke, using cheap blueprint paper to make photograms in the bathtub of their basement apartment on the Upper West Side. Here’s his recollection of the situation from his 1976 Smithsonian catalogue:

This period was exciting and prolific even if quality was erratic. We were both doing a minimum of five works a day. Clyfford Still came to the house to select a show with Betty Parsons. I was so naive and excited that by the time of the opening several months later, the selected show had been painted over dozens of times, and was a completely different concept. Betty was surprised.

Surprise became the operative mode for No. 1. After Cage got it, Rauschenberg was staying at Cage’s apartment while his loft was being fumigated for bedbugs, and he surprised/thanked the composer by painting over No. 1 with black enamel and collaging it with black-painted newspaper. According to Michael Kimmelman’s obit for Rauschenberg, “When Cage returned, he was not amused.”

Christie’s says this happened “a year or so later,” but Kimmelman says “As Mr. Rauschenberg liked to tell the story,” it was right after the Parsons show, which closed June 2nd. Rauschenberg and Weil’s son Christopher was born in July. And according to his 1976 chronology, he/they went to Black Mountain College in the “early part of the fall.”

But the Black Paintings, which seem to have followed the White Paintings, are dated as late 1951-1952. [Kimmelman reverses them, but Hopps’s catalogue quotes an October 1951 letter from Bob to Parsons talking about them as faits accomplis. I thought Kenneth Silverman’s John Cage bio Begin Again might help, but it is hopelessly inaccurate about dates for Rauschenberg’s works, and he doesn’t seem that interested in chronologies, either. He jumbles events from several years into single paragraphs, or omits dates altogether. And he doesn’t mention the bedbug thing at all. But anyway. I think the Black Paintings come to a hard stop in 1952. Rauschenberg was back at BMC in the summer when his white paintings were included in Cage’s formative Theater Piece #1 and subsequently contributed to Cage’s composition of 4’33”. Then he left for Europe that fall with Cy Twombly, leaving his soon-to-be-ex-wife and son behind.]

And so, perhaps unsurprisingly, the details and reported dates and circumstances of paintings created during this rather complicated time are themselves rather complicated.

A comment the artist made to Calvin Tomkins in 1980 about the Black Paintings seems apt:

“I was interested in getting complexity without their revealing much. In the fact that there was much to see but not much shown.”

But wait, there’s more!

This famous painting was subsequently again modified in 1985, when, it had become in need of some restoration. Rauschenberg chose to paint it completely all over in black again and bestowed upon it an accompanying note referring to the, by this time, historic and continuing dialogue that Cage and Rauschenberg had then enjoyed in both their art and their lives for over thirty years. The note reads: “This is part of the history of this single canvas – I hope the dialogue continues for many more years. I will if John dares, love Bob Rauschenberg.”

While it’s tough for the collector–or the auction house–who wants their 1951 painting to look old, the conception of a canvas as a constant site of activity, dialogue, and collaboration is pretty fascinating.

As Rauschenberg said of Short Circuit in 1967, when he showed it for the first time in over a decade:

This collage is a documentation of a particular event at a particular time and is still being affected. It is a double document.

Double and then some. Short Circuit, of course, included a program from an early Cage concert [which I’m trying to identify, btw] and a painting by Weil, though in 1967-8, the painting was hidden behind a nailed-shut cabinet door. [There was also that Ray Johnson collage, which contains a reproduction of a Renaissance nude.]

Anyway, I would think that with current imaging technologies, it would be possible, if not trivial, to examine Rauschenberg’s No. 1 for traces of the three paintings it used to be. Perhaps such an investigation could be combined with a closer reconstruction of the pivotal period in which it was created. As Rauschenberg himself put it, there is much to see, but not much shown.

An Avalanche Of Awesome

I’ve been kind of busy, and I didn’t want to get fingerprints all over the signed edition, and my few original issues are in storage somewhere, so I’m really only now getting a look at Primary Information’s beautiful facsimile copy of Avalanche magazine. I’m on page nine and I’m tempted to blog my way through the whole thing. Just so much going on. Here’s a taste from Avalanche No. 1, Fall 1970, from Rumbles, the front-of-the-book, which reads like the alumni news section of Conceptual Art University:

James Turrell, 27-year-old LA sculptor, who has not formally exhibited since his only one-man show of projected light works organized by John Coplans at the Pasadena Art Museum in 1967…In April 1969, Turrell and Sam Francis made a sky drawing using two World War I biplanes, radio-controlled from the ground, as part of Easter Sunday in Brookside Park organized by Oliver Andrews, Judy Gerowitz [!] and Lloyd Hamrol, who participated with elemental outdoor projects…

…

Work began this summer on Paolo Soleri’s Arosanti, a rural housing complex for two thousand inhabitants on a seven acre site seventy miles north of Phoenix, Arizona…

…

The Museum of Conceptual Art opened on Wednesday, March 18 in San Francisco’s Market Street district with a participatino piece in which buckets of paint were given to the guests to paint the walls white….MOCA’s latest show, Sound Sculpture As a one night presentation of successive sound events by ten Bay Area artists, was held on April 30…Allan Fish‘s piece was performed by Tom Marioni. Perched atop an eight foot ladder, he pissed into a galvanized washtub. As the tub filled, the sound dropped in pitch. He was followed by Terry Fox, who scraped a shovel across the linoleum floor and vibrated a thin plexiglas sheet very fast. Jim McCready paraded four girls wearing shiny nylons down a 3×9′ long rug. As they rubbed their thighs together a swishing sound was heard….

…

Andy Warhol…now has financial backing for his first Hollywood-based film, Specimen Days, the story of Walt Whitman’s experiences as a Civil War male nurse. With shooting set to begin around mid-October in New Orleans, the regulars are ready but the lead is still to be cast. Allen Ginsberg, Mick Jagger, and John Lennon have all turned it down.

…

After his recent New York visit, LA based artist Terry O’Shea has returned to California and plans to execute a large-scale ecological project involving fast-growing plants.

…

The Japanese police detained San Francisco artist Paul Cotton for wearing a pink bunny costume to the Pepsi Pavilion at Osaka’s World’s Fair. John Perreault gave Marjorie Strider his old Iowa summer teaching job so that he could concentrate on his first book for Abrams, Andy Warhol

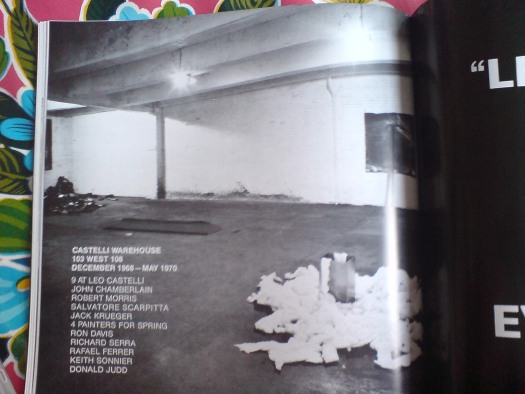

Ooh, an ad for 9 at Leo Castelli, the seminal show Robert Morris curated at Castelli Warehouse–which was not the Castelli Warehouse from which Jasper Johns’ Short Circuit flag painting was taken, but still.

Ooh, a big picture of the misty Pepsi Pavilion surrounded by moving sculptures in the ad for Robert Breer’s show at Galeria Bonino? Where is Robert Breer these days, btw? That’s not a rhetorical question, either.

The trade edition of Avalanche is under $100 at Amazon. The first nine pages, at least, are highly recommended.

Art In Process: Reading Finch College Museum

Now we’re getting somewhere, even if it’s only to the library.

Since the Finch College Museum was originally [and wrongly] fingered as the site of the theft of Johns’ Flag from Rauschenberg’s Short Circuit, I’ve been looking for months to buy a copy of the 1967 exhibition catalogue for Art In Process: The Visual Development of a Collage. Well, not so easy. Increasingly desperate and frustrated with the failings of the Internet Age, I decided check the library. Turns out the Smithsonian’s Museum of American Art library, right next door to the Archive of American Art, had a copy. Took like two minutes.

Art In Process was a series of topical, process-oriented, teaching exhibitions organized by Finch College Museum director Elayne Varian. They included sketches, models and studies to show how the artist did what he was doing. From Finch, which was on East 75th Street, the show traveled for 18 months to nine other smaller museums around the country in a tour organized by the American Federation of Arts. [Thanks to the original press release, provided by the AFA, the list of venues is below.]

I’m not the only one who had trouble finding the catalogue, though. Paul Schimmel’s huge Rauschenberg Combines catalogue said the flag painting was stolen while Short Circuit was on exhibit. That’s how he read the entry in Walter Hopps’ 1976 retrospective catalogue, which mentioned Finch and the missing flag together.

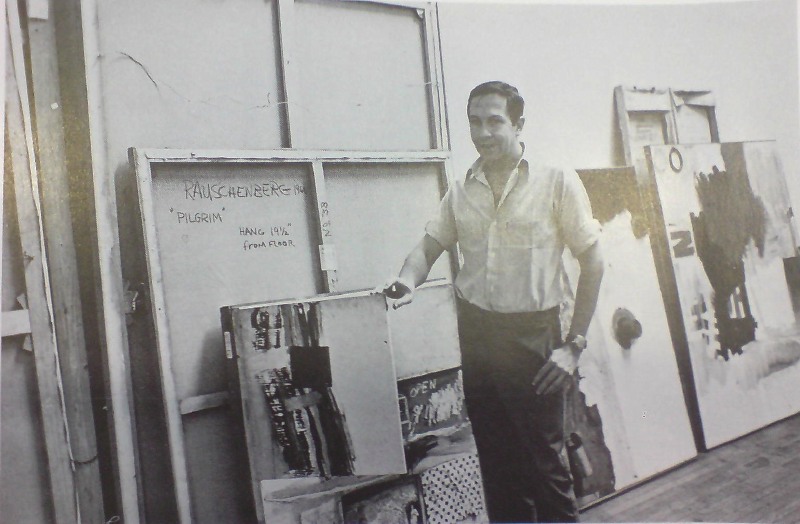

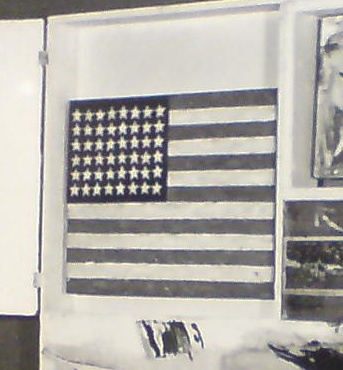

But. Check out what Rauschenberg actually said. Well first, check out that photo!

It’s Bob, teasing us with what’s behind Short Circuit Door No. 1. Because there is nothing:

In the third Artist Show at the Stable Gallery, my collage, SHORT CIRCUIT, 1955, was motivated by the protest that there had not been any new artists invited to exhibit. Therefore, I invited four artists: Jasper Johns, Stan Vanderbeek, Sue Weil and Ray Johnson to give me works to be built into my collage. Only two paintings were ready in time to be installed into the major piece. The collage also contains the autograph of Judy Garland, and one of the first programs of a John Cage concert. Because Jasper Johns’ flag for the collage was stolen, Elaine Sturtevant is painting an original flag in the manner of Jasper Johns’ to replace it. This collage is a documentation of a particular event at a particular time and is still being affected. It is a double document.

Give me. Built into. My collage. Only two. Is painting. These are the phrases that jump out at me.

Not only was Art In Process the first acknowledgment of the removal of Johns’ flag, almost two years after it happened, it was the first public exhibition for Short Circuit since Alan Solomon’s group show at Cornell in 1958. After being the subject of some kind of joint, post-breakup negation agreement between Johns and Rauschenberg, where the combine was not exhibited, published, or even, it seems, discussed, Short Circuit went on a cross-country tour, without the flag, and with the doors nailed shut.

I thought I’d be all Errol Morris about it and date the photograph from the other works in the background, but it doesn’t really help: Pilgrim (1960), on the left without its chair; Johanson’s Painting (1961), in the middle, with the tin cans, was in Ileana Sonnabend’s collection; the other combine painting with the N or Z element, I haven’t found yet. [Any ideas? Send’em in!] That watch Bob’s wearing looks like the one in the Avedon photo on the cover of Schimmel’s Combines, which was taken in 1960. But I’ll say Bob’s face looks a few years older, at least five, if not seven.

So this photo was probably not, then, taken before 1965. And Johns’ flag painting is probably not, then, behind that door. And Bob is probably not, then, toying with the terms of the no-repro “solution” he and Johns devised for this double document.

Other things: Sturtevant’s flag sounds like it’s in process. Unless that “Sturtevant is painting an original flag” is the same tense as “I am making an animated musical,” somewhere well short of “she’s delivering it this week,” and closer to “well, we’ve talked about it.” Because though a Sturtevant flag sighting was reported in 1971, There were no photos of Short Circuit for Hopps to publish in 1976, and Rauschenberg talking of painting a flag himself because he “need(s) the therapy.” And when David Shapiro and Hirshhorn curator Cynthia McCabe scouted the combine out in 1985, they had a “very sad experience” looking at the work, in a “state of real disrepair,” with mentions only of the absence of Johns’ flag and none of Sturtevant.

No mention of Ray Johnson’s inclusion. How classic for Johnson’s own collage that it gets subsumed so totally as Rauschenberg’s. It’s as if only the paintings can hold their own against the combine’s powers of assimilation. Resistance is futile. I guess that’s the real question here.

For Johnson, though, it’s probably the giddy answer. He was also included in Art in Process on his own, so don’t sweat for him. If anything, that’s how he wanted it. Here’s writer/artist/curator Sebastian Matthews:

Over the next decade, Johnson made a series of anti-rectangle collages. It wasn’t long before Johnson was mailing out collage fragments “for others to use or send on,” letting go authorship (at least in part) and allowing the work to be formed by increasingly random collaborations. No coincidence, then, that Johnson made this creative leap during his transition from Black Mountain to New York City while hanging out with his BMC buddies.

That’s from Matthews’ proposal/thesis for an awesome-sounding show, BMC to NYC: The Tutelary Years of Ray Johnson, which he organized last fall at Black Mountain College + Arts Center in Asheville, NC. Sounds like Short Circuit was as formative and in harmony with Johnson’s emerging practice as it was problematic for Johns’. That may be too simplistic, but it’s way past time to take a closer look at the rest of Short Circuit, too.

The dimensions: The Finch catalogue lists the dimensions for Short Circuit as 48 x 48 inches, which, since Bob was not seven feet tall in that picture, is obviously wrong.

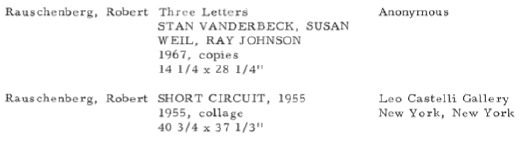

Another reason for checking the Finch catalogue was to see whether Short Circuit was still owned by Rauschenberg or, if it was still, as Michael Crichton reported, in Leo Castelli’s collection. And it doesn’t say. But the press release might. Artists, like Al Hansen, were listed as lenders for some works in Art In Process, but works were credited to the artists’ dealers. Short Circuit was apparently lent not by Rauschenberg, but by Leo Castelli Gallery. The mounted photocopies of letters to Ray Johnson, Stan Vanderbeck [sic] and Susan Weil, meanwhile, were lent “anonymously.” Wait, the what?

Continue reading “Art In Process: Reading Finch College Museum”

‘Happens To Like Flags!’

So I thought I’d check Jasper Johns’ bibliography to see if there was a review for Alan Solomon’s group exhibition at Cornell, which included Short Circuit.

There was not, but after seeing the first entry for 1958, from Johns’ hometown paper, I really don’t mind:

“Allendale Artist Paints What He Likes-Happens to Like Flags!” Chronicle (Augusta, Ga.), April 6, 1958. Discusses March 31, 1958 issue of Newsweek.

‘Construction With J.J. Flag’

tiny detail of a Robert Rauschenberg registry, dated 1957-9, which I can’t reproduce in full because of the terms of access to the Leo Castelli Gallery Archive at the Archives of American Art

Another day back in the Leo Castelli Gallery papers at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, and barely further along in my project to piece together the surprisingly complex history of Robert Rauschenberg’s Short Circuit.

After finding Castelli’s insurance claim for the “loss” of the Jasper Johns flag painting which was originally included in Short Circuit–a claim which makes absolutely no mention of Short Circuit itself or Rauschenberg–and reading Michael Crichton’s first published account of what happened, I wanted to see if there was any record of Short Circuit entering Castelli’s collection.

There was not.

The folks at the AAA who’d processed Castelli’s archive had already warned me that there was remarkably little personal material, and little relating to Castelli’s own collection. Nevertheless, there were plenty of traces of Leo’s own holdings scattered throughout the files; when Rauschenberg’s Bed was discussed, for example, Castelli’s ownership of it was at least mentioned.

What I came to see, though, is that especially when compared with other combine paintings from the 1950s, or, other works in Castelli’s and Rauschenberg’s collections, Short Circuit was almost completely absent from the ever-increasing stream of notes, discussion, and paperwork related to the artist’s career.

It’d be weird to lay out all the places that Short Circuit wasn’t, but I’ll give two examples: until the 1965 insurance claim, it never showed up in the photo reproduction orders the gallery sent to Rudy Burckhardt, who apparently shot all Rauschenberg’s [and other Castelli artists’] work at the time. In early 1967, when the gallery was negotiating with the British writer Andrew Forge to publish Rauschenberg’s first monograph, Short Circuit was not included in any otherwise comprehensive-seeming works lists or photo lists he received.

I have to think this negation-by-withdrawal is linked to Rauschenberg’s breakup with Johns, and to what Johns referred to in 1962 as the “solution of differences of opinion between him and me over commercial and aesthetic values relating to that work.” So long as had Johns’ flag painting in it, Rauschenberg was to keep the work out of public circulation.

In fact, the only archive mention of Short Circuit at all before Rauschenberg’s 1976 Walter Hopps retrospective, is in an early artist’s registry. The looseleaf, ledger paper list is dated 1957-59, when Rauschenberg and Johns were together and both having groundbreaking first solo shows at Castelli [in 1958, Johns in January, and Rauschenberg in March].

And technically, it wasn’t even Short Circuit; it was listed as “Construction with J.J. Flag,” with the dimensions and date, “40 x 36 1/2, 1955.”

There’s alo a handwritten notation that the work had been exhibited at Cornell University in the spring of 1958. That would be the second showing Johns had referred to in 1962. [The first, the 1955 Stable Gallery show for which it was created, is not mentioned.] The idea that Short Circuit–a work which merged the two artists’ signature innovations–was exhibited immediately after their controversial, back-to-back, solo shows would seem like big news. But no. Paul Schimmel’s 2005 Combines catalogue only lists the “group exhibition” in a footnote, and I haven’t found any other reference to the show online. In 1958, the director of the Cornell Museum would have been the critic/professor Alan Solomon, who was tight with all those Poppy guys. [He’d go on to curate definitional Pop Art shows in 1962.] I’ve contacted Cornell; we’ll see if they have anything on the show.

If there was a “difference of opinion” about publicly displaying Short Circuit, I think we can assume that Johns did not want it shown, and Rauschenberg did. Because soon after the flag painting was removed, Rauschenberg put the combine into Elayne Varian’s traveling collage exhibition at Finch College Museum–with the doors nailed shut.

It’s funny, all this time I’ve been poking around this piece, I’ve thought of it in terms of “getting the Johns back.” But when you think about it, the one who got his work back in this caper is Rauschenberg.

UPDATE: Whoa, I just noticed that the dimension mentioned above–40 x 36 1/2″–don’t match up at all with those given in Hopps’s 1976 catalogue: 49 3/4 x 46 1/2. What up? Is “Construction with J.J. Flag” NOT Short Circuit after all? It is an error, another missing flag/combine combo, or an upending of the original Stable Gallery story? If the Johns flag is 17″ or so, there is no way that piece above is 50″, or even 46″. Gagosian lists the dimensions as 40 3/4 x 37 1/2″, which is close enough for me. No sweat, Hopps & co just had bad info.

Like Some Michael Crichton Novel

Maybe it’s the CSI-ification of everything, but as I dig through archives and piece together timelines, and interview people–oh, I haven’t really mentioned the interviews, have I?–while trying to track down the story of Robert Rauschenberg’s Short Circuit and its little, missing, Jasper Johns Flag, I sometimes feel like a character in a John Grisham novel.

Maybe it’s the CSI-ification of everything, but as I dig through archives and piece together timelines, and interview people–oh, I haven’t really mentioned the interviews, have I?–while trying to track down the story of Robert Rauschenberg’s Short Circuit and its little, missing, Jasper Johns Flag, I sometimes feel like a character in a John Grisham novel.

Which is funny, because the greatest book I’ve found on Jasper Johns so far is by Michael Crichton. Seriously, with his 1977 book, Jasper Johns, created for the artist’s mid-career retrospective at the Whitney, Crichton defined the exhibition-catalogue-as-pageturner genre.

After my most recent visit to the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art last week, I had a few minutes to spare, so I ducked into the Museum of American Art Library across the hall to flip through Crichton’s catalogue and to see if there was any mention of Short Circuit in the supposedly exhaustive catalogue for Anthony d’Offay’s 1996 show of Johns’ Flags. [There wasn’t, and though it had a couple of good ideas, David Sylvester’s essay was uncharacteristically uninteresting.]

Well, flipping through Crichton’s book was riveting. I could only read a few pages, but it felt like a mystery, a suspenseful, personal investigation into the artist, his thinking, his process, and his work. It was chock full of quotes from people who know and work with Johns, evidence of Crichtons’ conversations and interrogations. I wanted to read every one. And it was only the recurring image of my kid waiting, alone, on the curb outside her pre-school, wondering why her daddy had forgotten her, that forced me to stop. It’s an intense, infectious curiosity that I admit I haven’t really felt towards Johns’ work before.

In the course of this recent, somewhat intense look at Early Johns, I’ve been struck and sometimes a bit put off by the artist’s apparent/reported hermeticism, his opaqueness. Not that I want art spoon-fed to me, or served up like some all-I-can-consume Baselian buffet. But if Johns wants to be obscure, closed, personal, private–yeah, I’ll go with closeted–then fine. Far be it from me to pry. And far be it from me to take advantage of that reticence by projecting my own theories and interests and speculations on the artist and his work, as a great deal of critical writing about Johns seems to do.

But while he addresses and acknowledges Johns’ seemingly impenetrable work and persona, Crichton also quotes a close friend saying something like, no, “Jasper wants to be understood.” [I’ll look it up later when my copy of the catalogue arrives.]

the very flaggish, hinged In Memory of My Feelings – Frank O’Hara, 1961, Art Inst. of Chi., via NPG

And that, coupled with the remarks from the curators of “Hide/Seek” that it was the first time Johns has ever allowed his work to be seen in a queer context [that link it to Michael Maizels’ discussion of the show], makes me feel that this longer, closer look at this painting–these paintings–is not just alright, but right. And that Johns would agree.

Anyway, the point is, buy this book. No, no, the point is, Johns rewards close, intense looking, and Short Circuit, both in its original state and throughout its fraught, altered history, feels like a key touchpoint in the works, lives, and careers of these artists. And it turns out that no one has gotten its story totally straight yet, not even Michael Crichton.

There is a note in Crichton’s Johns story that begins:

As a curious historical incident, a Johns painting was seen at the Stable Gallery in 1956, as part o a Rauschenberg painting.

Actually it was 1955. But then there’s this bombshell:

Leo Castelli later acquired the Rauschenberg with the two doors. He kept the painting in his warehouse. One day he examined the painting and dsicovered that the Johns flag had been stolen.

Wait, what?? Castelli bought Short Circuit? So it was not, after all, in Rauschenberg’s personal collection his whole life after all. And I only find this out after I leave the Castelli Archive. I wasn’t even looking for this kind of stuff. While it explains what Short Circuit was doing in Castelli’s warehouse, it doesn’t explain when Bob sold it, or why Leo bought it. Or why or when Bob got it back.

The artist Charles Yoder told me last month that Short Circuit was in Bob’s collection–and had Sturtevant’s replacement Johns Flag when he went to work for Bob in 1971. [Though the first published mention of Sturtevant I can find is still the Smithsonian’s 1976 catalogue, which ended up using Rudy Burckhardt’s original, Johns-era photo.] I guess I’ll have to get back to the Archive and look for Castelli’s own collection records. And his correspondence with Bob. And then look for the 1967-8 Finch College Collage checklist and/or catalogue, to see who was listed as the owner of Short Circuit, which was, remember, still described as containing a Johns Flag behind its nailed-shut doors.]

So this means that sometime between–well, we really don’t know when it was, just sometime before June 6, 1965–Castelli bought Short Circuit. And found the Johns Flag missing. But Crichton’s not through. “Castelli recalls a final incident in the story,” he writes:

Years later, a dealer–we do not need to say who–came to me and said, “Someone has brought me this Johns painting and I don’t kno wit, and I wondered if you could tell me about it, the date and so on.” I knew immediately what it was; it was the stolen painting. I said, “The painting has been stolen and I would like to keep it right here. I don’t want it to leave my gallery.” But this person said he had promised the person he got it from, and he didn’t feel he could leave it with me, and he said he would have to talk to the other person, and he was very insistent. So I said, “Well, all right.” I never saw the painting again.

“Castelli recalls”! “We do not need to say who”!

Well, this saves me a trip into Calvin Tomkins’ archives at MoMA; because I will bet that Crichton’s footnote is the source for the secondhand version of this incident Tomkins included his 1983 Rauschenberg bio. And where Tomkins ended broadly–and obviously wrongly–with “and nobody has seen it since,” Crichton nails the quote from Castelli: “I never saw the painting again.”

Which puts us back to where this whole thing started. Except that I think I now know–because I have been told by people who would know–who that dealer was, and who he was presenting the painting for. And based on some interviews I’ve done since, I am pretty sure I’m right.

But that turns out not to be the same as figuring out when the Johns Flag went missing, or more importantly, where it went, and where it is now. And even when Crichton quotes Castelli himself as calling the painting “stolen,” and I’ve seen it mentioned [albeit as “lost”] in an insurance report, when Castelli had the painting back in his gallery–and had chance to get it back from someone he obviously knows–he let it walk out the door again.

Michael Crichton died unexpectedly in 2008 while undergoing treatment for throat cancer. His art collection, including the Flag painting he bought directly from his friend Jasper Johns, which he considered his single most important acquisition, was auctioned last Spring at Christie’s. Mike Ovitz waxes a little hagiographic, and I deeply don’t get the Mark Tansey thing, but the video that Christie’s produced about Crichton and his passionate, intellectual engagement with art is really pretty good.

Measuring 17.5 x 26.75 inches, Crichton’s Johns Flag [above] is much smaller than the Flag which Castelli first saw in 1958 in Johns’ studio, an experience he later called, “Probably the crucial event in my career as an art dealer, and… an even more crucial one for art history.” It was slightly larger, though, than the Flag in Short Circuit [13.25 x 17.25 in.]. And it was painted between 1960-66, exactly the time when Short Circuit‘s Flag was being contested and lost–and shortly before Castelli got it back, and let it walk back out of his door. Crichton’s Flag sold in May 2010 for $28.6 million.

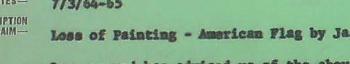

‘Loss of Painting – American Flag – Jasper Johns’

So here is where, after a few months of searching, I basically get caught up to the editors of Johns’ collected writings, who noted in 1996 that Johns’ Flag painting disappeared from Leo Castelli’s warehouse sometime “before June 8, 1965.”

After a couple of days of digging through the newly opened Castelli Gallery archives at the Archives of American Art, I found that date on the gallery’s insurance claim reporting the “Loss of Painting – American Flag by Jasper Johns valued at $5000 $12,000.” [the higher figure is written in by hand.]

The insurance company’s memo acknowledging the claim said that “Mr. Mellors is to meet with the assured on Wednesday afternoon regarding the details of the claim.”

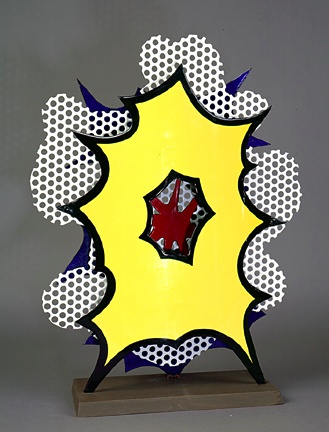

June 8th was a Tuesday, and sure enough after his visit, Mr. Mellors had more to add. A follow-up memo is titled more clearly, “Theft of Painting – 6/6/65 – “Desk Explosion 65″ by Lichtenstein.” Mr. Mellors, it said, “…when discussing the loss on “American Flag” by Jasper Johns was informed of the above loss by Mr. Castelli.”

So what we have now is not just a “before June 8,” and a “loss” [although that is still the word used in relation to the Johns], but a date: “June 6” and a “theft.” And not just one work, but two.

The only other documentation I could find is a small note, “Call headquarters for 9th Precinct,” “Warehouses/ 75 Cliff St/ 25 First Ave” and the name [?] “Kay Kaz.”

The 9th Precinct is the East Village, which makes me think it was the First Avenue location. Kay Kaz, I have no idea, and I can’t find anything online so far. But this was not Leo’s handwriting, so I am assuming someone was taking this information down on the phone.

Frankly, I can’t tell if I’m more Law & Order: Art Victims Unit or Columbo, but this is feeling very real to me, trying to piece together what happened, where, when, and with whom, just using a few old memos.

The 6th was a Sunday, so it seems as if someone made a weekend visit to the warehouse, found the Johns missing from Short Circuit, called the police, then called the gallery to give instructions about following up with the police. And then on Tuesday, they filed a claim for the Johns, while seeing if anything else was missing. And by Wednesday, they found a Lichtenstein gone, too.

As it turns out, both works are similarly sized: small and portable. The Johns Flag is 13 1/4 x 17 1/4 inches, and Desk Explosion is 20 x 16 x 4–wait, 4-in? It’s a sculpture. An enamel-painted metal freestanding sculpture on a 4-inch deep base, made in an edition of 6:

Small….Explosion (Desk….Explosion), 1964, : image via lichtensteinfoundation.org

Either way, maybe tracking the Johns is now a matter of tracking the Lichtenstein.

So what do we know now? First, that the AAA’s Castelli Archive is awesome. I could blog those boxes out for days if the photo restrictions were a little more conducive. Instead, I find them more illustrative of the way that art historical information is still transmitted: in relatively hermetic dribs and drabs.

My previous assumption that the Johns may not have been “stolen” stolen because it was never reported as such turns out to have been wrong. Well, those reports existedtl, anyway, even if the Johns wasn’t exactly described as “stolen.” [I was also wrong about a couple of other assumptions and speculations I made in earlier posts, which I’ll get to separately and soon.] But generally, the information I’m finding does appear to have been found by at least someone, sometime, before. So I wonder what I’m doing: if all these curators and scholars have already been over this before, am I just playing art detective for my own belated educational amusement?

But questions still arise that keep me on the hook:

- Where’d those precise dimensions come from? Castelli? Rauschenberg? Johns himself? Someone had them on hand at the time the police were notified. I guess that answers the question about whether the Flag was an autonomous work?

- Why were Rauschenberg or Short Circuit not mentioned at all in the insurance claim?

- And the claim–and a half dozen 8×10 glossies of Rudy Burckhardt’s original photograph of Short Circuit was in Castelli’s Johns file, not his Rauschenberg file? [Just end it with an uptone and it becomes a question.]

- And what was Short Circuit even doing in Castelli’s warehouse? Wasn’t it in Rauschenberg’s own collection his whole life? In which case, why wasn’t he filing insurance claims on it?

- What IS up with that Lichtenstein?

- Rudy Burckhardt?

- And obviously, who is Kay Kaz, and what’s s/he doing in the middle of the memo about the polce?

‘Someone May Have Located The Stolen Painting’

It’s exactly the kind of scribbled note I dug through five boxes of Smithsonian archival material hoping to find: “Someone may have loc. stolen ptg. So Charles will talk to Bob about it.”

Well, I talked to Charles about it. The artist Charles Yoder worked for Robert Rauschenberg for five years, until around 1975-6. So I called him, and unfortunately, he had no idea where the Johns flag painting was, the one which had been removed from Short Circuit in the mid-60s [Michael Crichton says before 1965.] He did say there was “scuttlebutt,” at the time, a general awareness that there was a Johns flag painting on the loose. But it never went beyond the, “I heard some guy was trying to sell it on the Bowery,” type urban legendry.

But though I didn’t find any smoking guns, or burned flags, in the records from Walter Hopps’ 1976 Rauschenberg retrospective at the National Collection of Fine Arts, I did learn some more interesting details about Short Circuit and its complicated history.

Like, for one thing, the 1955 combine was not actually shown in Hopps’ retrospective.

Continue reading “‘Someone May Have Located The Stolen Painting’”

Short Circuit Flag: Finch Is Off The Hook

There’s some interesting background info as well, but the big news [sic] today in piecing together the history of Rauschenberg’s Short Circuit is that Finch College is off the hook–and Holland Cotter is right after all.

Continue reading “Short Circuit Flag: Finch Is Off The Hook”

Jasper Johns’ ‘Short Circuit’ Flag: One Place It Isn’t

After a brief break, during which I briefly pwned Miami Art Basel, the search for the Jasper Johns flag painting which was included in Robert Rauschenberg’s 1955 combine-painting Short Circuit [above], continues.

Actually, because I had to carry on the oddball contents of the gift bags I did for my #rank presentation, I went to the airport freakishly early and ended up with extra lounge time, which let me read through all the details and footnotes in my pristine, OG copy [apparently from the library of Artforum!] of Dr. Roberta Bernstein’s definitive 1985 dissertation-cum-catalogue raisonné, Jasper Johns’ Paintings and Sculptures 1954-1974, “The Changing Focus of the Eye.”

Only guess what, it wasn’t there. Not a mention, not a photo, not a footnote, not a trace.

[UPDATE: Since posting this in December, I have communicated with Dr. Bernstein about the Short Circuit flag and its absence from her thesis, as well as its status in her forthcoming Johns catalogue raisonne. Scroll down for her gracious and informative reply.]

Continue reading “Jasper Johns’ ‘Short Circuit’ Flag: One Place It Isn’t”

This Flag Is My Flag. This Flag Is Your Flag.

Something Holland Cotter wrote today made me really think: “Short Circuit is a sweet reminder of Rauschenberg’s collegial generosity; he believed in art making as a communal endeavor, and acted on that belief.”

Collegial generosity is certainly one way to look at it. Because Rauschenberg had exhibited in the Stable Gallery’s Second and Third Annuals, he was supposed to be able to select artists to show in the Fourth Annual. For whatever reason, though, in 1955 Eleanor Ward decided only Stable alumni would be allowed in that year, and so Rauschenberg’s picks–Short CircuitJasper Johns, Ray Johnson, Stan VanDerBeek, and Susan Weil–were rejected.

And so the story goes that Rauschenberg smuggled them into the show anyway, as elements in his own combine painting. [It’s not clear why VanDerBeek’s work wasn’t included; Cotter says he didn’t get a piece finished in time, but I’ve also read that VanDerBeek declined the combine invite.]

Rauschenberg invited the artists to, as Walter Hopps put it, “collaborate in his piece.” A generous gesture, to be sure, but also a complicated one.

Short Circuit triggers a whole host of questions that I find the quite interesting: What is the status and relationship of the artworks Rauschenberg incorporated into his combine-painting? Do they still function as autonomous works? If so, why? Are they substantively different from the other cultural detritus he used–newspapers, postcards, fabric, objects? If not, why not?

In the bluntest sense, these questions are answered by the invitation for the show, which mentions none of Rauschenberg’s three collaborators:

Rauschenberg’s generous inclusion of his ex-wife’s painting, his friend’s collage, and his partner’s iconic flag painting–oh, wait, that’s right, this was the first flag painting of Johns ever to be exhibited, and it was as an element of another artist’s work–and behind a door to boot. Did anyone in 1955 even know that Jasper Johns’ Flag wasn’t Robert Rauschenberg’s flag?

The story of Johns’ promethean debut at Castelli Gallery in 1958 is well known. In this 1969 telling of it to Paul Cumming, Castelli visits Rauschenberg’s studio in 1957, and then they pop down to Johns’ studio, which is full of targets and flags, and Castelli offers him a show on the spot. Which makes the cover of Art News and changes the New York art world overnight. But check this out:

Jasper Johns was a real discovery in a certain sense because, although he existed, not many people knew about him. I saw him for the first time in a show at the Jewish Museum. That was in March of 1957, and that was the Green Target that the Modern has now. I saw that green painting. It didn’t, of course, appear as a target to me at all. It was a green painting. I didn’t know that he was doing targets. Well, going around and seeing the familiar painters of that time…. It was a show that had been organized by Meyer Schapiro and other people. There was Rauschenberg and Joan Mitchell, and, oh, all that younger generation. Well, I came across that green painting, and it made a tremendous impression on me right away. I looked at the name. The name didn’t mean anything to me. It seemed almost like an invented name–Jasper Johns.

[Emphasis added on the parts where, holy crap, two years after exhibiting Short Circuit, there’s still a question whether “Jasper Johns” exists.]

Johns had shown flags at Bonwit Teller [including White Flag, which he eventually gave to the Met], where he and Rauschenberg dressed windows under the commercial pseudonym Matson Jones. Except for a drawing in a group show, Johns only exhibited a flag painting under his own name in 1957, in a group show at Castelli a few weeks after their fateful studio visit.

Rauschenberg’s Short Circuit–and Johns’ first and most immediately important paintings of flags and targets–were created when the two artists were closest, and when Johns was essentially unknown. When the flag was stolen from Short Circuit, both artists were famous, and their split was so acrimonious, they were not speaking to each other.

These relationships and collaborations, these formative histories of the New York art world, and these contestations of autonomy, authorship, sourcing and appropriation all seem to converge on Short Circuit. And it makes me wonder, again in the bluntest terms, whose flag was it, and who was it stolen from?