The inconvenient intrusion of war and political upheaval [i.e., the collapse of the Dutch government and the looming withdrawal of Dutch troops from their frontline deployment in Afghanistan] into my Dutch Landscapes project has sent me trying to re-find some discussion of Vermeer that's stuck with me for years.

Like so many hundreds of thousands of others, I made a trip to the National Gallery in Washington in the winter of 1995 to see the first Vermeer exhibition in almost 300 years. It was a DC that may be hard for folks today to even conceive of: the show was abruptly opening and closing, thanks to massive snowfall and two government shutdowns orchestrated by an obstructionist Republican agenda led by Newt Gingrich. [I know, right? He seems so nice.]

Anyway, 21 of the world's 35 Vermeers were there, including View of Delft, loaned by the exhibitions only other venue, the Royal Gallery at the Mauritshuis in The Hague.

The Essential Vermeer puts the date depicted in the painting as early May, 1660 [the evidence: leaves on the trees, the boat activity, and the empty tower on the Nieuwe Kerk, because the bells were in the shop]. It seems so banal, so placid, so idyllic.

But I remember reading a discussion of how deceptive, or at least complicated, this peace was, in light of Delft's own history. The argument centered on the high-contrast beam of sunlight Vermeer punched through his rainclouds to illuminate the Nieuwe Kerk, in the center background of the painting.

William of Orange had used Delft as a base for launching in 1568 what became the Eighty Years War, against Spain, the Hapsburgs, and the Holy Roman Empire, which turned on issues of religious intolerance, taxation without representation, and centralized power. William was assassinated in 1584, and because his family's traditional seat, Breda, was still in Spanish hands, he was interred in the Nieuwe Kerk. So are his successors in the House of Orange-Nassau, who continued the fight, and who have ruled the Dutch Republic since it won its independence with the Treaty of Westphalia, which was signed on May 15, 1648.

But wait, there's more! In 1660 the city was also still recovering and rebuilding after the Delft Thunderclap of 1654, a massive gunpowder explosion at a waterfront munitions warehouse that killed over 100 people--including one of Delft's most well-known painters, Fabritius Carels--injured thousands more, and leveled a huge section of the city.

If Vermeer were alive in 2013, then, the equivalent painting might be the rainy skyline of lower New Amsterdam from the Hudson, where a ray of sunlight picks out the details of an unobstructed St Paul's church--if George Washington and all the subsequent presidents were buried there. If there's a Dutch equivalent of a bald eagle with a tear in its eye, Vermeer showed remarkable restraint by not including it.

UPDATE I'll get out my DVD set in the morning to confirm, but I think Tyler Green's right, it's the first essay in Lawrence Weschler's 2004 book, Vermeer in Bosnia, which was originally published as "Inventing Peace," in The New Yorker, Nov. 20, 1995.

Yep, here we go, Weschler's setup for the remarkable story of how the head of the International War Crimes Tribunal in The Hague kept himself sane by looking at the Vermeers at the Mauritshuis:

For, of course, when Vermeer was painting those images, which for us have become the very emblem of peacefulness and serenity, all Europe was Bosnia (or had only just been): awash in incredibly vicious wars of religious persecution and proto-nationalist formation.

Wow, maybe I should re-read the whole thing rather than post updates every page, but. Weschler quotes Harry Berger's idea about Vermeer's deployment of "'conspicuous exclusion,' of themes that are saturatingly present but only as a

felt absence."

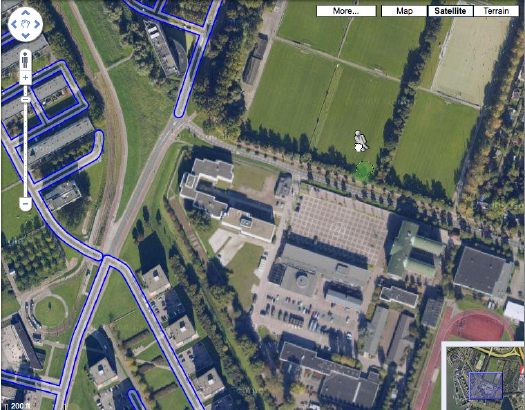

What a fantastic phrase, which immediately reminds me of a comment left by Jerome Bertrand on Ogle Earth's original 2006 coverage of the Dutch Google Map censorship issue:

All the same, someone at Royalty level (AIVD?) would choose to typically blur out certain private residences - so it ends up you can find them quicker than others by just scanning for blurred spots in the area. This is helpfull [sp] when you need to know what's hot.