I know a lot of you have been asking yourselves, “Hey, what’s been going on with Greg and the Belgian Waffle?” No? Too bad. Cuz I’ll tell you.

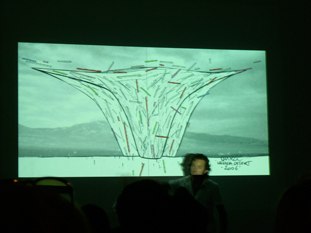

The Burning Man curator known as LadyBee and I have been going back and forth in email over whether Uchronia’s creators co-opted Burning Man as a backdrop for their own alternabrand-enhancing PR, whether the 1,000+ photos on flickr tagged with Uchronia constitutes a brand now, or whether Arne Quinze and his co-designers are just sending out 50,000 books and DVD’s to “people in important or influential positions who help shape the socio-economic landscape and can make a difference” anonymously and with no expectation of personal benefit.

Now, as you can imagine, an MBA, ex-consultant, ex-banker would have a hard time taking a credible stand against marketing, branding, or PR, but that’s not my point, and it hasn’t been. I don’t think there is anything intrinsically wrong with marketing per se, but I give Burning Man the institution full credit for not launching Black Rock Consulting, but instead sticking to their non-commercially exploitative guns.

But it’s naive of me to have thought as I have all these years, that Burning Man somehow exists apart from the society it sought to leave behind. Just as the environmental and resource impacts of the playa can’t be overlooked–they do still share a planet, an atmosphere, and a Wal-mart distribution infrastructure with the rest of society, after all–the notion that what happens in Black Rock City stays in Black Rock City is a fantasy. And all the bartering in the desert won’t change the fact that Burning Man is a brand and an institution in itself now, and it has associative value that the Uchronians identified and skilfully leveraged–and they did it in a way that has Burning Man veterans defending them.

While LadyBee has been pretty engaging, if resolute in her defense of the Uchronians, [“of course Arne puts them on his resume – and why shouldn’t he? He designed and built the thing. All our artists do that. If it strengthens his portfolio, fine. What marketing scheme do you think they’re going to unleash? Selling imported radiators to burners?” (Arne Quinze’s co-creator Jan Kriekels has a radiator company)], and she backed off a bit from her first email [“subject: greg – get a clue!”], the Belgian she roped into our exchange started with a really petty, thin-skinned personal attack.

Burning Man’s foundation is the idea that everyone could and should make art or express herself creatively. BRC is built on that creative exchange. Great. But Burning Man also has a curator, and a grant-making and evaluation process, which they use to dole out a portion of gate receipts to art proposals. It’s an institutional system that bears a remarkable ressemblance to the non-playa-based art world.

Uchronia itself was funded completely outside that institution, as LadyBee explained in an email to Burning Man’s staff [who’d apparently had some questions about the project, too.] And its team included between 45 and 60 “volunteers,” who, it turned out, were employees of the creators’ companies, and who worked at full salary, plus expenses, on the project. By that definition, Star Wars was a “volunteer” project, too.

Again, this is all totally cool, but it seems to me that if what happens at Burning Man doesn’t stay at Burning Man after all, and there are curatorial decisions being made and business transactions being done, then these people could respond a little better to criticisms, alternative interpretations, or a response that’s anything less than sheer, uncritical gratitude and ecstasy.

When Christo “gave” the “Gates” to the world, he kept trotting out his figure for how much he spent–$20 million, he said–while the boost the project gave his own art sales and holdings–in a private, pre-“Gates” interview, Jean-Claude claimed they had $400 million–was almost never mentioned.

The “Gates” was what it was, and Uchronia is what it is. But one of the things it is is a page in a portfolio for a “creator of atmosphere” who sells his own brand of edgy counter-cultural buzz to corporate clients like Compaq, Diesel, and Rem Koolhaas.