I just got the first prints of Dutch Landscapes to paint. And I’ve captured a few more to prep for printing. Here are a few more of the camo-obscured Dutch sites I also like but haven’t gotten around to capturing and printing yet. Most are military or intelligence installations of some kind, culled from the Onherkbaar/Unrecognized list here:

View Larger Map

The landscape and architecture around this one on the Maas in Rotterdam has a really nice, explicit geometry of its own. The light in some of these is just wonderful, too. So strong and clear. Which is what you’d want, obviously, for aerial photomapping. As Stefan reported on Ogle Earth back in 2006 when this dataset debuted, the fact that these were not satellite images is intrinsic to their camo censorship. Satellite imaging is considered to be beyond Dutch jurisdiction, but permits are required for aerial surveying, and the images are reviewed to censor “vital” military or intelligence buildings and sites.

View Larger Map

More landscape geometry. This one reminds me of Isamu Noguchi’s admiration of hatake, the rice paddy landscape of Japan, a terrain which, like the Netherlands, was the product of centuries of intensive human sculpting and engineering. [That said, I can’t find any mention of the Noguchi quote I’m thinking of.]

View Larger Map

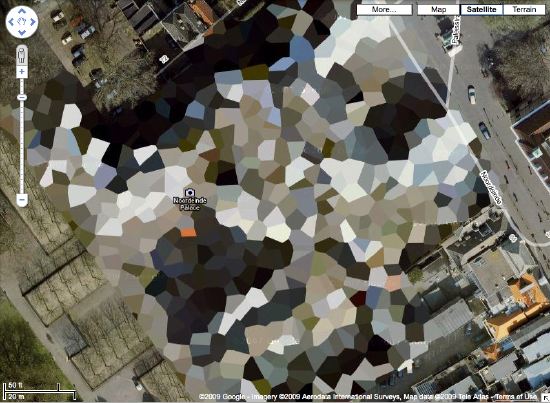

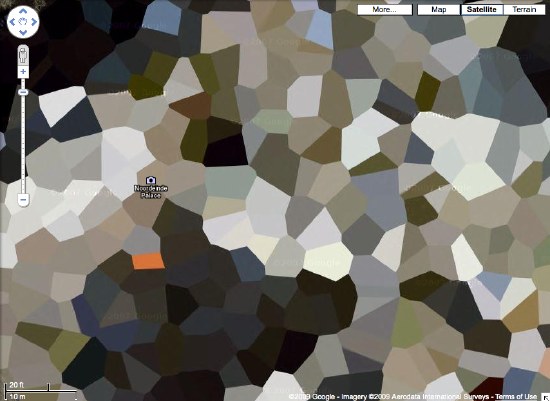

This one’s the Palace Huis ten Bosch, the Queen’s residence. I love that the tennis court and the sculpture garden at the top are not considered “vital” sites. While trying to identify any of the installed works, I learned that H.M. Queen Beatrix is quite a fan and practitioner of sculpture and maintains at studio there at the palace.

Category: google

What I Looked At Today

So I decided to make the Dutch landscape paintings I wanted to see made from those incredible security-obscured Dutch Google Maps I found a couple of weeks ago.

I’ll print the images out and paint over them. Since they are Dutch landscapes, I figure they’ll be nice, little domestic-sized paintings I can make on a table.

I’ve been trying to puzzle out how to get the paint on there and what it should look like. My first idea was to keep the process as mechanical as possible, both to produce crisp, sharp polygons, but also to mediate between the image and me–and my utter lack of painting experience or technique. But my brother-in-law, an excellent artist with an extraordinary sensitivity to technique and material, made the case for just painting the damn things with a brush.

So I’m convinced, though I’m still not quite settled on how I’ll do them. But we set out today to look upclose, extremelyclose, at some 17th century Dutch landscape and cityscape paintings, and see how they were done. Of course, we missed the much-hyped Dutch Cityscapes exhibition at the National Gallery last spring.

Here’s what we saw today at the National Gallery:

Gerhard Street View

A Google Street View image of a French radar-jamming installation obscured by order of the Ministry of Defense or an overpainted photograph by Gerhard Richter? You decide.

Houses Of Orange

NL Architects thinks it might make a good Herzog & deMeuron project, but I think Google Maps’ security pixelization of the Dutch Royal House’s Noordeinde Palace in Den Haag would make an absolutely fantastic series of landscape paintings.

Where else in the world are such things? The DRH’s summer palace at Huis ten Bosch; an AZF chemical weapons factory in Toulouse…

There’s a surely incomplete list of obscured satellite images on Wikipedia, and a map. Which includes Mastercard’s corporate headquarters in Westchester, which actually looks like it was painted over. They call it “watercolored.” Perfect.

here’s the list of camo’d Dutch sites I’ve been working with.

Previously:

architecture for the aerial view, including WWII factory roof camouflage: the roof as nth facade

art for the aerial view: Calder on the roof

Aluminaire House: The Making And Remaking Of

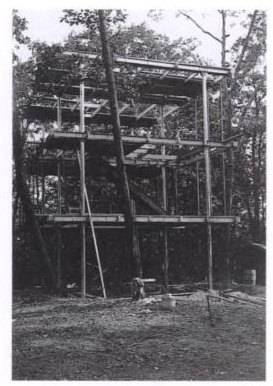

Haha, It only took ten days the first time. When Wallace K Harrison reassembled Kocher and Frey’s Aluminaire House on his property in Huntington, LI, after buying it for $1000 and taking it apart in a matter of hours, it took a lot longer and cost a lot more. That was due, “in part because the components for the house were left outdoors and a strong rain washed away the identifying chalk markings, leaving a jigsaw puzzle to be put back together.” Ultimately, the structural integrity was compromised, and anyway, Harrison soon added onto and moved and later even partially buried what he called the “tin house.”

Haha, It only took ten days the first time. When Wallace K Harrison reassembled Kocher and Frey’s Aluminaire House on his property in Huntington, LI, after buying it for $1000 and taking it apart in a matter of hours, it took a lot longer and cost a lot more. That was due, “in part because the components for the house were left outdoors and a strong rain washed away the identifying chalk markings, leaving a jigsaw puzzle to be put back together.” Ultimately, the structural integrity was compromised, and anyway, Harrison soon added onto and moved and later even partially buried what he called the “tin house.”

That’s all according to the 1999 revised edition of Joseph Rosa’s Albert Frey, Architect, which is on Google Books.

Rosa also gives some hint as to the house’s structure and materials, none of which sound like they’d pass muster with a building department today:

- the whole thing rested on six five-in. aluminum columns attached to aluminum and steel channel girders.

- the “battle deck-pressed steel flooring” was sandwiched with insulation board and linoleum.

- the non-loadbearing walls are “narrow-ribbed aluminum,” insulation board, and building paper, “joined by washers and screws.”

- the dining room and living room were separated by a glass&steel china cabinet, a retractable rubber-top dining table, and the risers for the shower cantilevered from the bed/bath overhead.

- the balcony was lined with concrete-asbestos brick.

Fantastic, but seriously crazy. The only way you could logically cantilever a shower over a living room is if it has glass walls. Which sounds like something Paul Rudolph would do, or probably did.

Who What? Kocher & Frey’s Aluminaire House?

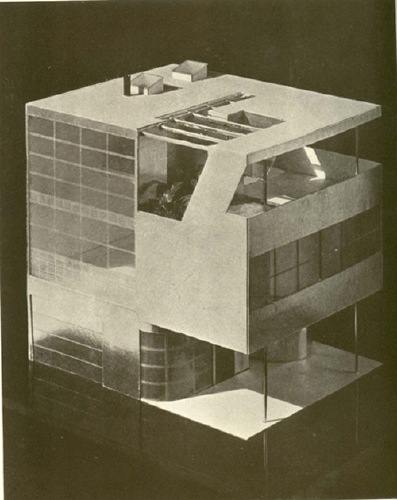

Let me get this straight: the first modernist prefab in the US; one of two US houses included in Phillip Johnson’s 1932 International Style exhibition at MoMA [the other: Neutra’s Lovell House]; built in 10 days from off-the-shelf industrial materials, with no formal plans or blueprints; Albert Frey’s first US project; bought and disassembled in hours, then saved and bastardized by Wallace K. Harrison; quoted nearly perfectly–concept, materials, and form–by Kieran Timberlake in their Cellophane House; and yet somehow Aluminaire House itself was not included in “Home Delivery,” MoMA’s 2007 show on the history of the modern prefab Please tell me I just missed it or blocked it from my memory.

But I’m hardly the only one.

Lawrence Kocher was editor of Architectural Record and later involved with Black Mountain College. The 27-year old Albert Frey was fresh off the boat from Le Corbusier’s studio. They whipped up Aluminaire House from donated parts and materials for a 1931 building show and Architectural League exhibition at Grand Central Palace, an expo hall that filled the block between 46th and 47th streets and Park and Lex.

Kocher’s concept was a light-filled, modernist prefab house made of innovative, industrial, mass-produceable materials: aluminum, steel and glass. The 3-story, 5-room, 28×22-ft, 1,200 sf building was barely more than a mockup, an exhibition pavilion. Frey later compared it more to a refrigerator than a building in its construction; it was light steel bolted together with nuts and washers and skinned in ribbon windows and corrugated aluminum, a material Frey would use extensively in California. The floor was ship decking covered in linoleum. Interior walls were rayon fabric. It was supported on five aluminum pilotis.

The main living space [LR/DR, Kit, MBR, BA] was on the second floor. The living room was double height, open to a partially enclosed library/2nd bedroom on the third floor, which also had a terrace. A second bathroom with shower was cantilevered over the living room, which frankly sounds like a joke.

Harrison bought the Aluminaire House for a thousand dollars after the expo ended, and reassembled it at his house on Long Island. In ’32, Johnson showed the house in the International Style exhibition, but didn’t include it in the catalogue. Harrison proceeded to enclose the ground and third floors and add on some circular structures, rendering the house nearly unrecognizable.

Which is why it was almost demolished in 1987-8 when Harrison’s estate was chopped up and developed. The architecture department of the New York Institute of Technology took the Aluminaire House on as a school project. They studied and dismantled it, then eventually reassembled and restored it on a new pad on their Central Islip campus. Which looks to be about 10 minutes south of Exit 55 on the LIE, within easy pilgrimage visiting by every design snob in the Hamptons.

And yet, no one really seems to care or know about it. In a brief blurb about a 1998 Arch. League show on restoring Aluminaire House, Herbert Muschamp got the location and story of the house wrong. No one who writes about it sounds like they’ve actually seen it. There aren’t any contemporary photos of it online, only one shot from Harrison’s yard.

It’s on Google Maps, of course, and that’s Microsoft’s Bird’s Eye view on the right. But no mention of it on NYIT’s site. [The architecture department was moved from Islip to a campus in Old Westbury, so if it served any academic purpose before, the Aluminaire House seems kind of orphaned now. A 2007 messageboard post said that it was to be relocated as part of a redevelopment/selloff of part of the campus. If it hasn’t happened yet, I’m sure it won’t happen for a while.

But it sounds to me like there’s an unloved, unappreciated pile of historic modern awesomeness in the middle of Long Island that needs to be liberated and returned to loving domestic use. At the very least, will someone take half an hour on the way to the beach and go shoot some freakin’ photos?

The only lengthy discussion of Aluminaire House I can find online: docomomo’s 1998 Modern Movement Heritage by Allen Cunningham [google books]

Le début du point de vue Google Mappienne

On June 19, 1885 Gaston Tissandier and Jacques Ducom set off in across Paris in a balloon. They were on a photo expedition, and managed to get seven shots. This one, of the pont Louis-Phillippe, at the western tip of the Ile St-Louis, was the most successful, in that it was nearly straight down. Though it was not the first aerial photo of Paris, it caused a sensation and was exhibited and reproduced widely for many years.

The photo historian Thierry Gervais wrote about it in a 2001 article in Etudes Photographique, “Un basculement du regard, Les débuts de la photographie aérienne 1855-1914”:

In 1885, Gaston Tissandier and Jacques Ducom know the objectives and results of aerial photographs obtained by Nadar. When they fly over the capital on June 19, their goal is clear: “After many attempts, it still needs to be demonstrated that the proofs obtained in a balloon may be as sharp as those taken on land in the ordinary conditions and resolve in a word completely the problem of free balloon photography.”

Beginning at the Auteuil aeronautical workshop, the 13 x 18 camera, known as a touriste, is set on the edge of the platform, with the lens oriented to the ground. The crossing of Paris is done from Porte d’Auteuil to Ménilmontant via a light wind from south-west which takes them up to Meaux. Seven photographs are made, five of the capital and two of the banlieue. If “all are good enough to be reported,” that of the Ile Saint-Louis holds particular attention, taken at 600 meters, this photograph is of a perpendicular sharpness that “leaves nothing to be desired.”

The photograph of Île Saint-Louis gained real notoriety. Mentioned in the columns of le Bulletin de la Société française de photographie, it was noted that “now that any party was able to shoot the Geography, Topography and Military Arts,” it will be reproduced on many occasions. It is published in an article in la Nature describing the expedition. In 1886, Gauthier Villars printed rotogravure and photoglyptie in the book of Tissandier titled, La Photographie en ballon. Two years later, Albert Londe chooses to illustrate his chapter on aerial photography in La Photographie moderne. In 1889, it appears alongside the tribute of Paul Nadar at the Exposition universelle.

But the diffusion also means that the photograph of the Ile Saint-Louis is one-of-a-kind in the late 1880s. Tissandier and Ducom’s experimentation was not followed by an intensive production of aerial photographs. Commandant Freiburg made several attempts to shoot from a balloon, but the military are confronted with a problem context. To be out of reach of projectiles, the balloon must be at least 5000 meters. Accordingly, the camera needed to be equipped with a telephoto lens to produce legible images. Having noticed, during the Exposition of 1889, the value of aerial photography for the strategy, the military focuses its attention on getting results with long lenses.

What strikes me is how little has changed in over 100 years, at least from this perspective.

Here’s the same shot today on Google Maps:

Bought A Bing

And in other “laughable corporate attempts to build brand equity through campaigns designed to intentionally genericize trademarked-but-tangential phrases that rhyme with ding-a-ling” news:

Microsoft’s marketing gurus hope that Bing will evoke neither a type of cherry nor a strip club on “The Sopranos” but rather a sound — the ringing of a bell that signals the “aha” moment when a search leads to an answer.

The name is meant to conjure “the sound of found” as Bing helps people with complex tasks like shopping for a camera, said Yusuf Mehdi, senior vice president of Microsoft’s online audience business group.

And if Bing turns into a verb like, say, Xerox, TiVo or, well, Google, that would be nice too. Steven A. Ballmer, Microsoft’s chief executive, said Thursday that he liked Bing’s potential to “verb up.” Plus, he said, “it works globally, and doesn’t have negative, unusual connotations.”

Mhmm. “Verb up.” I wanted to Twitter about leaving a Zing! on Bing, but the URL just redirects to decisionengine.com.

Microsoft’s Search for a Name Ends With a Bing [nyt]

two’s a trend?: Miracle Whip: The App

IRL: Art On Google Maps Smackdown

Paddy Johnson is taking the search for art on Google Maps to a place it’s never been before: In Real Life.

This Saturday, at Capricious Space in Brooklyn, Paddy is hosting a Google Maps artwork faceoff, a real-world, real-time challenge between two artists, James Turrell and Alice Aycock, to see which artist has more works visible to Google’s Eye In The Sky.

Check out details and get a headstart online at ArtFagCity. Meanwhile, I’ll be checking Capricious on Google StreetView regularly; I better not see you loafing around outside with the smokers.

In Real Life: James Turrell and Alice Aycock Face off on Google Maps! [artfagcity.com]

“Calder on the Roof”

In 1967 Henry Geldzahler, while lecturing the Women’s Group at the Grand Rapids Art Museum, suggested to Mrs LeVant Mulnix III that the city might do well to install a public sculpture on the plaza in front of city and county buildings being designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. Mrs Mulnix promptly wrote to Congressman Gerald Ford to ask for assistance in obtaining a grant from the newly established National Endowment for the Arts for the commission.

SOM senior partner William Hartmann, who was at that time completing the installation of Picasso’s monumental sculpture in front of the firm’s Chicago Civic Center, came in to consult on the project. Alexander Calder was chosen, and La Grande Vitesse which sits on Calder Plaza, has been the symbol of the city for decades.

Grand Rapids was the beneficiary of the friendship forged between Calder and Mulnix, and in 1974, the artist made a gift to the city of Calder on the Roof, a giant red, black and white mural executed on the roof of the Kent County Administration Building.

The work was intended to be seen from the surrounding buildings, which basically means the adjacent City Hall. Of course, it looks pretty sweet on Google Maps, too.

Google Earthwork: JR’s Projet Women Of Kibera

Well that didn’t take long. From the always awesome Wooster Collective comes word of a new work by the underground artist JR, Projet Women of Kibera, part of his ongoing 28 millimetres series he has been working on since 2004.

JR shot portraits of women in Kibera, a poor neighborhood alongside the train tracks in Nairobi, Kenya, and printed them on roof-sized vinyl, which was installed on the womens’ roofs. The photos are visible from the train–and from Google Earth–and the vinyl also helps keep the rain out.

And when Google Maps takes a higher-resolution pass over the slums of Nairobi, it’ll be visible there, too.

JR Finishes His Most Ambitious Project Yet [woostercollective]

JR’s portfolio site [jr-art.net]

See a whole slew of Kibera photos as the 28 Millimetres site [28millimetres.com]

Heads Up: Roof As nth Facade

The first place I remember hearing the idea of the roof as a “fifth facade” was Peter Eisenman talking about his Columbus Convention Center, from 1989, but completed in 1993.

With an awkward, constrained site sandwiched between downtown and a tangle of freeways, Eisenman recognized that the most important vantage points for the building were from the air–from passing motorists, conventioneers’ hotel rooms, and arriving airplanes. So he translated his program of entry lanes and loading bays sculpturally across the building.

You’d think the triumph of the rendering and virtual formmaking software and the whole, architecture as sculpture/object era would have heightened sensitivity to 360-degree design. But Google Maps makes it immediately clear that architects can be divided into those who consider the roof, and those who consider the roof an easy place to hide the air conditioner. Well, it ain’t hidden any more, folks.

I was reminded of this while surfing through pmoore66’s vast collection of aerial views of modern and contemporary architecture. While there are definitely wholly considered designs that look good on Google Maps, there are a very few–like Toyo Ito’s 2002 pavilion for the Serpentine–which seem to give special attention to the bird’s eye view.

On the one hand, it seems obvious that this vast, global audience should be factored into the creation of architecture. But on the other, it seems absolutely insane to design a structure, a space, for people who won’t be anywhere near it, but sitting in front of some screen on the other side of the world.

Maybe the next Bilbao Effect, sure to appeal to striving cities in these difficult budgetary times, will be to commission grand architectural designs purely for the benefit of the Google Maps audience. Like the rural streetscape camouflage which was applied to the roof of the Lockheed airplane factory in Burbank to thwart Japanese bombers during WWII, cheap, easy, flexible Potemkin roof structures could really put a town on the map, so to speak.

Richard Serra Sculptures On Google Maps

The whole thing about the only human construct you can see from space is the Great Wall of China will be amusing to people growing up in the Google Maps era, where you can’t hide anything from the satellite’s surveilling eye. It’s the geospatial equivalent of explaining TV before remotes and cable: it’ll just make you sound old.

So kudos to Richard Serra for being ahead of the curve [no pun intended] on making work that turns out to be well-suited for viewing from our new conveniently God-like vantage point.

I started to make a list with the Torqued Ellipse in front of Glenstone, Mitch Rales’ foundation in Potomac, and the suggestion from Guthrie of T.E.U.C.L.A., a torqued ellipse in the Murphy Sculpture Garden behind the Broad Art Center at UCLA, described at its installation in 2006 as “the first public work by sculptor Richard Serra installed in Southern California.”

And that reminded me that the Broads have had a Serra titled No Problem in their backyard for a while, which, thanks to Google Maps, is now public. Searching for that image led me to pmoore66’s collection of bird’s eye view Serras around the world at Virtual Globetrotting. If you count Robert Smithson’s Amarillo Ramp, which he helped complete after Serra Smithson’s death [!], pmoore66 has sighted 44 Serras around the world using either Google Maps, or Microsoft’s Bird’s Eye View, plus another four shots on Google Streetview. [Here are the search results on Virtual Globetrotting for “Richard Serra”, but that link looks a little unstable.]

With more than 1,700 entries so far, pmoore66 appears to be almost single-handedly pinning down the modernist canon for architecture and outdoor sculpture. This warrants some looking into. Stay tuned.

The more oblique angles of birds-eye-view seems to suit Serra’s sculptures better, and they remind me of a series of little desk tchotchke-sized versions of monumental sculptures called minuments that I saw in the ICA London bookshop a few years ago. As soon as I can figure out how to get Google to stop spellchecking for me, I’ll get the artist’s name.

Serra From The Block

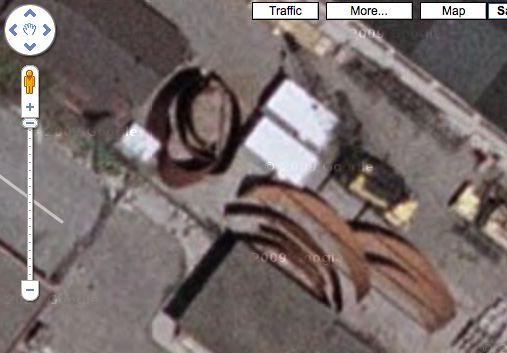

Someone is storing his Richard Serra sculptures along the East River in the Bronx. As massive, vertiginously curved steel plates are wont to do, they tend to stand out, and so they get noticed or discovered periodically.

Jake Dobkin spotted them recently, and posted pictures of one of the Serra sculptures behind a barbecue and a busted fence. It’s a Torqued Ellipse [1] with the steel plates curled in a bit tighter than normal. Jan included a shot of the works on Google Maps, where they look nice sitting next to a collection of steel gas tanks. It appears that the other sculpture, a collection of six arced slabs in graduated sizes, is the disassembled–and ironically titled–Blindspot, presumably purchased from the artist’s 2003 show at Gagosian.

[Note to self and/or someone else: figure out how many Serras are visible on Google Maps? Former Dia chairman Leonard Riggio’s got one parked on his front lawn in Bridgehampton; Wave is installed at the Olympic Sculpture Park in Seattle; Joe, the first Torqued Ellipse, is in the courtyard at the Pulitzer Foundation; St Louis also has Mark Twain, a much earlier Serra downtown; I’m sure the list goes on.]

The first mention I can find of these ersatz Bronx Serras is from a 2005 NY Sun story about redeveloping public park space along the waterfront in Port Morris. The lot owner, Curtis Eispert, whose main business is storing cranes, quotes the sculptures’ owner: “He says, ‘I love the way it rusts in the salt air.'” [Hmm, it also says, “One piece, a wide band of curved and rusting iron that sold for $2 million, sat on a flatbed truck waiting delivery.” Could Serra be the “someone” storing his Serras in the city?]

Eispert also mentioned an “‘artists’ loft'” [the Sun’s scare quotes, btw] across the street, so “artists” must be aware of the Serras, too. Sure enough, In August 2006, a group of artists put on a show inside the Torqued Ellipse. Lan Tuazon and Marie Lorenz curated Invisible Graffiti Magnet Show, which consisted of magnetic works attached to the Serra for one Sunday morning. The exhibit persists, of course, as a press announcement and a flickr photoset. Above: works by the collective Dearraindrop and Matt Lorenz. Below: an LED throwie constellation by Virginia Poundstone.

Actually, ignore the “artists’ loft”; after reading up on Marie Lorenz’ fascinating Tide and Current Taxi project, I’m sure she spotted the Serras from the water, not the land.

Port Morris, scroll down for the Serra links [bluejake via x-ref]

Bomb the Serra! [triplediesel]

richardlovesmagnets’ photoset [flickr]

[1] 2/17 update: OK, now we know it’s a torqued spiral, not a torqued ellipse. photographer/filmmaker/Jake Dobkin accompanier Nathan Kensinger revealed that the sculpture is Bellamy, a spiral first shown in 2001.

Mies Gas Station: I’m So Happy. Now I Have A Place To Put My Skyway

Alright, I know where I’m going to put my decommissioned Skyway: right next to my decommissioned Mies van der Rohe Esso Station.

Mies’ office designed three apartment buildings on l’Ile des Soeurs in Montreal beginning in 1963, which were joined by a gas station in 1968, a year before he died. [here’s the Google Map of the gas station. There’s no streetview.2017 update: Oh yes there is. And it had a bouncy castle.]

The building is on a corner, and is long and low and mostly a void. The most prominent feature, the black steel awning over the pumps, runs between a glass & buff brick box on one end [the store] and a glass & steel box on the other [the garage and office]. Looking at flickr member zadcat’s photos up close, the gas station looks mostly stock; there’s none of the material preciousness of, say, IIT’s custom profile I-beams, and forget about the Barcelona Pavilion’s meticulously matched marble, travertine, and onyx. This is a utilitarian building created by a mature architect’s office which, for better and worse, knew its way around the construction industry.

Tucked away on the far, quieter side of an already quiet residential island, the old school Esso station lost business to a newer, more amenity-filled competitor near the bridge, and it was recently closed. Now a debate is on about what to do with the property.

Toronto’s Globe & Mail reports that public hearings on the fate of the defunct building, now owned by some developer, were set for this week. There’s talk of a flower market which might leave the building pretty much as is, or maybe they make it into a youth center, which means destroying it by remodeling it.

The option that wasn’t mentioned in the paper–perhaps because the city peres in Montreal were graciously waiting for me to proffer it–is to let me have the building in exchange for dismantling it and removing it to a new site so I can live in it.

It’s already clear that even though it is his only gas station, its timing, and the process under which it was designed mean it is not a super-important example of Mies’s work. In other words, Montreal shouldn’t get too worked up about it.

And that same standard issue construction quality means you don’t necessarily need to sweat wrapping and numbering every brick and plate of glass.

Practically speaking, dismantling, moving, and rebuilding offers the aspiring gas station dweller like myself the best of all possible worlds: the sleek, authentic industrial architecture and space, in the ideal setting of your choice, with absolutely none of the environmental toxicity complications of the original site. The fact that you’re preserving and breathing new life into the work of a master of 20th century architecture is pure bonus.

But it’s the bonus that makes the whole concept possible. No run of the mill gas station is worth the irrational expense and hassle of dismantling, conservation, and reassembly. And while it’d be arguably cheaper and more practical, building a house from scratch that is a replica of a Mies van der Rohe gas station just seems sad and pathetic to me, like making yourself an exact copy of Southfork. No, saving a Miesian landmark provides the necessary conceptual cover to make an otherwise crazy plan seem rational, even imperative.

And then the Skyway can be my office and editing suite right next door.

You can come live with me, Ritz! The Ritz of gas stations looks for a new life [globe & mail, via archinect and tyler]

Chad loves Mies’s gas station [tropolism]

previous residential gas station fantasies here and here