I’ve been looking into how Google Street View panoramas are made, and it’s been kind of awesome. Each equirectangular panorama is stitched together on the fly out of 21 photos.

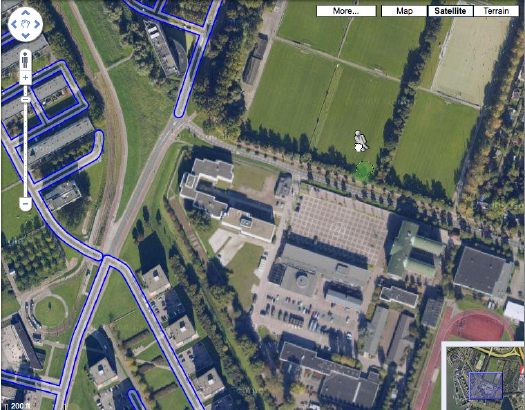

Equirectangular projection, or plate carrée (flat square), is a technique that maps coordinates onto an evenly spaced grid of latitude and longitude, which produces significant distortions, especially along the perimeter. Like how Antarctica ends up looking bigger than the rest of the continents put together. Flickr user swilsonmc’s images of flattened out Street View panoramas show the axis of distortion quite nicely.

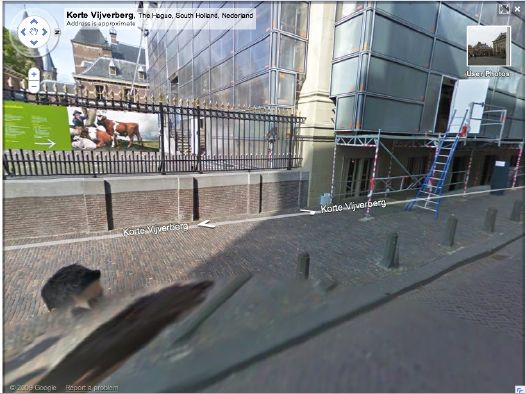

I think there are other distorting elements in Street View, though; it appears that each panorama is anchored to a specific set of lat/long coordinates. [The Street View data layer on Google Earth shows this beautifully by plopping these 3D pano bubbles down on its own 3D landscape. (top) It’s like simulation-within-simulation. Also, they look like inverted satelloons, only they’re projecting back their surroundings from the center, rather than reflecting from the surface. I mean, just check out the highly reflective surface of the PAGEOS global mapping satellite for a minute. Am I right? Wait, did someone say mapping?]

Anyway, the panoramas pull together the best images of that spot, which are not necessarily taken at that spot. Google’s roving cameras are shooting constantly, so there images approaching and leaving a particular panorama site. This introduces multiple POV and perspectival distortions into a single panorama. Which can result in awesome, zig-zagging thickets of tree trunks, fence posts, stanchions, and disembodied pedestrians. And which all remind us that these panoramas are not photos, but photomontages.

But wait, that’s not all! swilsonmc also created a php script that turns every flattened Street View panorama into a frame of video. The flickr video above shows the trip up the Long Beach Freeway in LA, from Seal Beach to Glendale. It reads as a continuous trip, of course, but if you watch the traffic and the clouds, the other Street View distortion–time–so obvious it’s invisible, becomes clear: there are photos taken on different days.

Roland Barthes described photography as “the presence of a thing (at a certain past moment).” The always didactic John Berger said,

Photographs bear witness to a human choice being exercised in a given situation. A photograph is a result of the photographer’s decision that it is worth recording that this particular event or this particular object has been seen

and on the intrinsic temporal content of photography, he said, “This choice is not between photographing x and y: but between photographing at x moment and not at y moment.” I think it becomes clear that in the traditional, theoretical sense, whatever Google Street View images are, they are not photography.