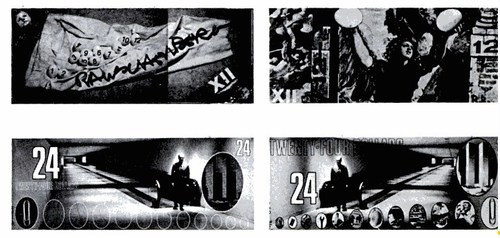

ArtCash by Rauschenberg (top) and Tom Gormley, via nymag

Whatever else it was, Billy Kluver, Bob Rauschenberg and Robert Whitman’s Experiments in Art & Technology was wildly successful at never selling out; the collaborative was constantly broke and getting bailed out by whomever they could find. E.A.T. was booted from the Pepsi Pavilion at Expo70 as soon as it opened over wild cost overruns. I saw a thick folder of invoices, IOUs, and pleas for petty cash in the Castelli Archives. I hear there’s an identical stack, probably even thicker, in the Foundation for Contemporary Arts. And then the other night, I find this 1971 article about art and money in [where else?] New York Magazine:

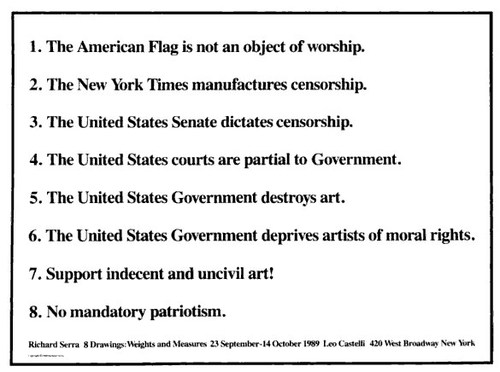

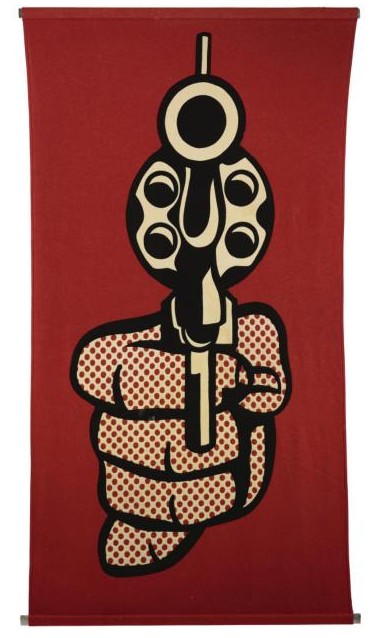

In the sixties several American artists, most notably Larry Rivers and Andy Warhol, used money as the subject of their paintings. Calling on their example, a broke E.A.T. organized a gambling event last week to finance further activities. Currency was designed by Warhol, Robert Whitman, Robert Rauschenberg, Red Grooms and Marisol [and Tom Gormley], on an escalating scale. But Swedish artist Oyvind Fahlstrom’s design was turned down for political reasons–it depicted Nixon inflating and deflating himself…Their gambling night was an amusing comment on the current situation as well as, hopefully, a way to outflank the museum-bank gallery-cartel syndrome.

The gambling night was held at Ted Kheel’s Automation House on the Upper East Side, which connected to the head end of one of Manhattan’s first cable TV companies. Proceeds were actually flagged for E.A.T.’s Community Television Center and Artists & Television program, which had solicited proposals for artist-produced TV shows.

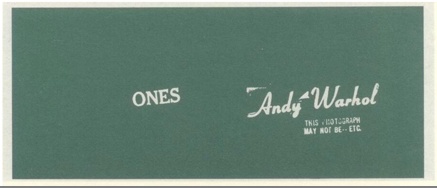

$25 got you $25 ArtCash bucks, which you could use to win “TV sets and original graphics.” At least a few people just took the ArtCash. According to the lot description of an unbroken $500 bundle of Warhol Ones at the 2009 Dumbo Arts Center benefit auction, the ArtCash bills were printed [but not engraved] by the actual American Banknote Company.

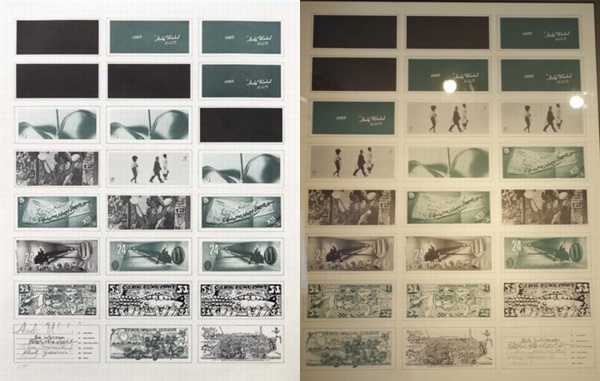

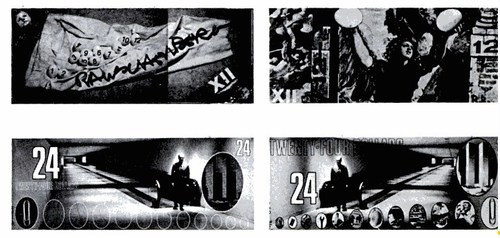

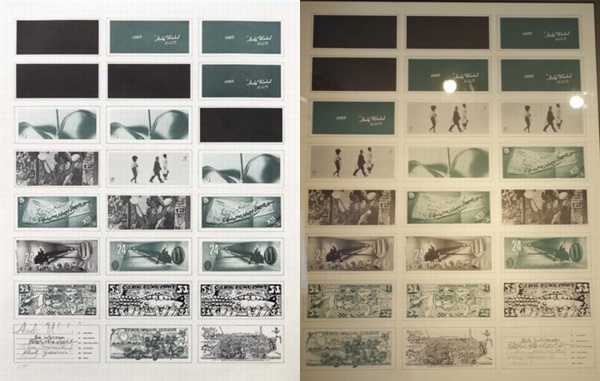

E.A.T. published three signed ArtCash posters showing either the fronts or backs of the various denominations. Here’s a composite showing two of the three [l via pdp; r via artnet]

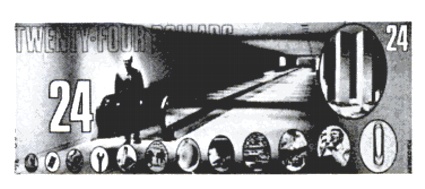

The denominations were $1 [Warhol], $3 [Whitman], $12 [Rauschenberg], $24 [Gormley], $51 [Grooms], and $88 [Marisol]. Which means each print had a face value of $468. Considering that Phillips sold the copy on the left for just $1,875 in 2008, these may be the worst-performing Warhols on the market.

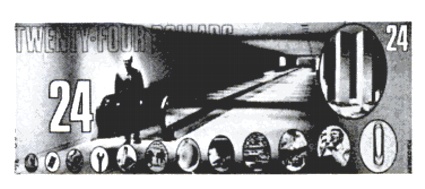

Whoa, in tallying that out, I took a closer look at each bill; Gormley’s look to include the World Trade Center, which might mean that that underground moving walkway is in Albany, which might make that figure there then-governor Nelson Rockefeller.

The E.A.T. Archives at the Getty includes several more stacks of ArtCash, including some by Jeff Davis, who, who?

Jan 2013 UPDATE: Good things come to those who blog. greg.org reader and/or ArtCash Googler Sarah Hollenberg of the University of Utah Art & Art History department writes that the Jeff Davis mentioned above is none other than the country’s greatest example of printing your own money, Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States of America. Hollenberg:

The bill that the Getty credits to him is by Red Grooms. They mistook the reference to Davis as a signature because they keep the bills wrapped up with a strip of paper, which covers up Grooms’ signature.

And now we know. Thanks!