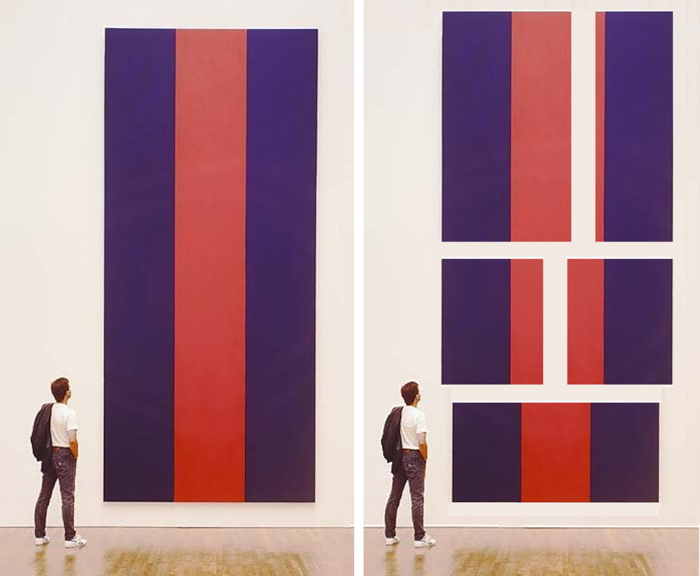

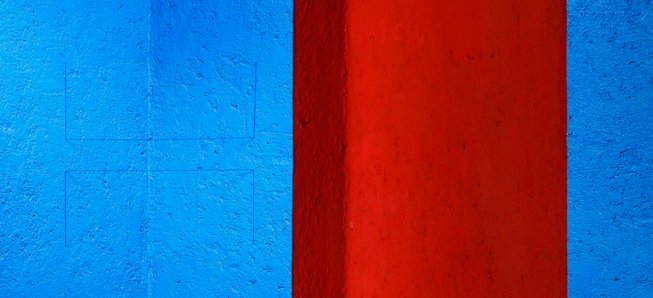

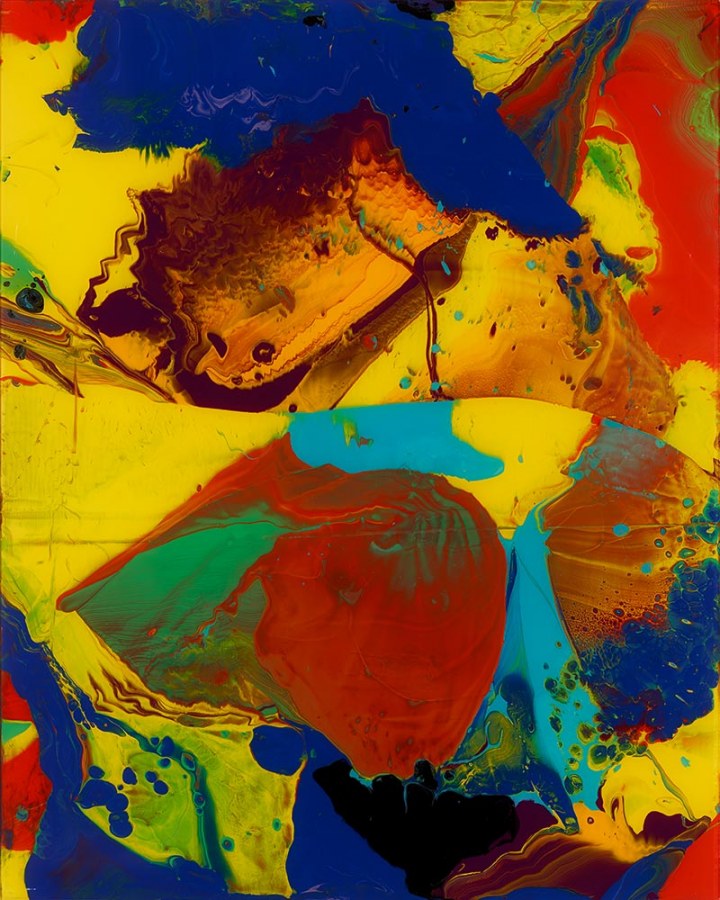

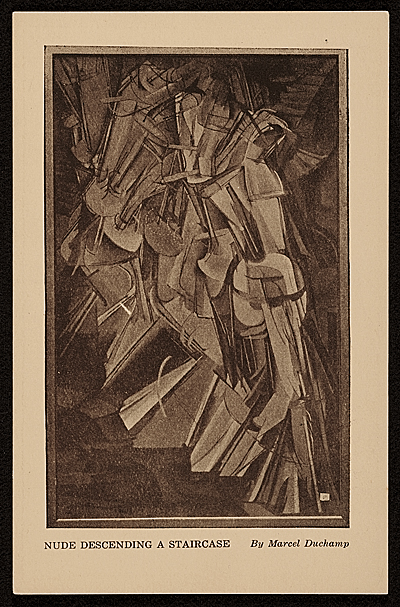

Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 3), 1916, 148.1 × 91.8 cm, image: philamuseum.org

Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 3), 1916, 148.1 × 91.8 cm, image: philamuseum.org

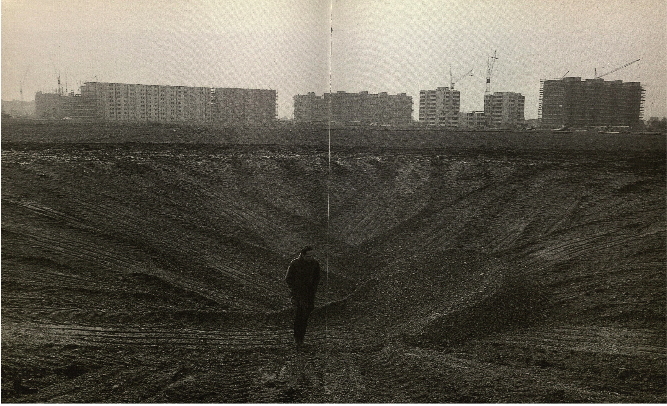

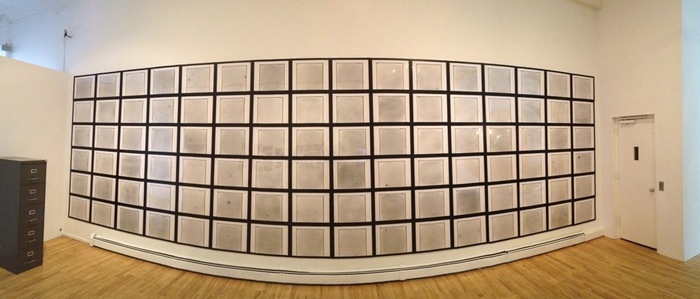

I’ve been enjoying Elena Filipovic’s 2013 dissertation, whose title says it all: “The Apparently Marginal Activities of Marcel Duchamp.” [pdf via monoskop, obv]. So far it’s about photography, including a long look at the so-called Box of 1914 (1913-14), in which Duchamp made 1:1 photos of a selection of his handwritten notes. The photos were mounted and put into repurposed, reworked commercial boxes from photoplates, and distributed to friends. As Duchamp would describe it later, the Box was a work in itself which would operate as a guide alongside The Large Glass he was designing. Of 5+1AP, only 4 survive. The Pompidou has the best pictures of it.

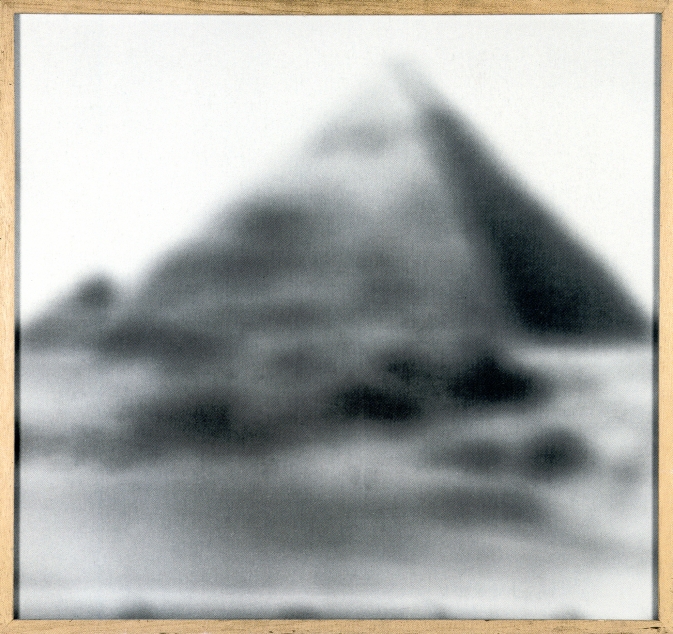

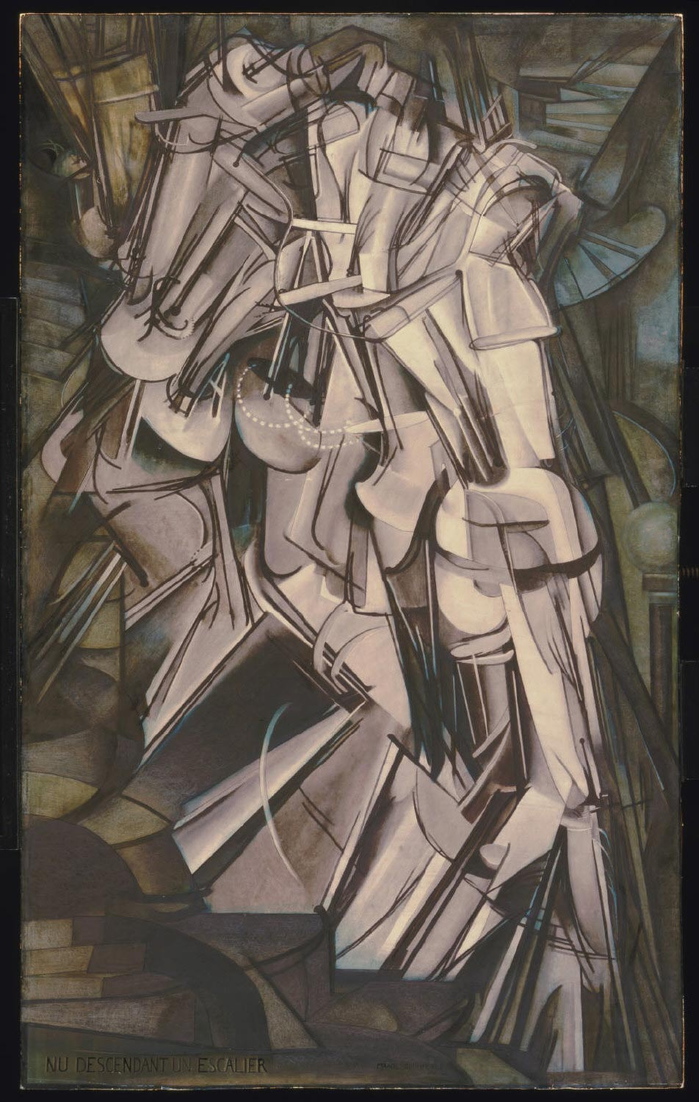

Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), 1912, 147 × 89.2 cm (close!), image: philamuseum.org

But Filipovic’s discussion of Duchamp’s early photo activities naturally includes one of my own favorite Duchamp pieces, Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 3), a full-scale photo copy of his most famous painting, which itself was inspired by the chronophotography of Etienne-Jules Marey, which he made for the Arensbergs in 1916. No. 3, that is, because, well, let’s let the Philadelphia Museum explain:

In 1916, Marcel Duchamp recreated his Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) for his patrons Louise and Walter Arensberg, who had coveted the notorious painting since seeing it at the Armory Show in New York three years earlier. Given that the original was now owned by a San Francisco art dealer who did not want to part with it, Duchamp had a commercial photography studio enlarge a postcard image of the work to match the proportions of the original canvas. The colossal photograph was then meticulously retouched by the artist in a wide variety of mediums, including pencil, ink, watercolor, and pastel, to replicate the crisply delineated forms of the original composition.

#Actually, as Filipovic points out, Duchamp did not have access to the painting, and he did “not at all attempt[…] to replicate the original painting’s color scheme.”

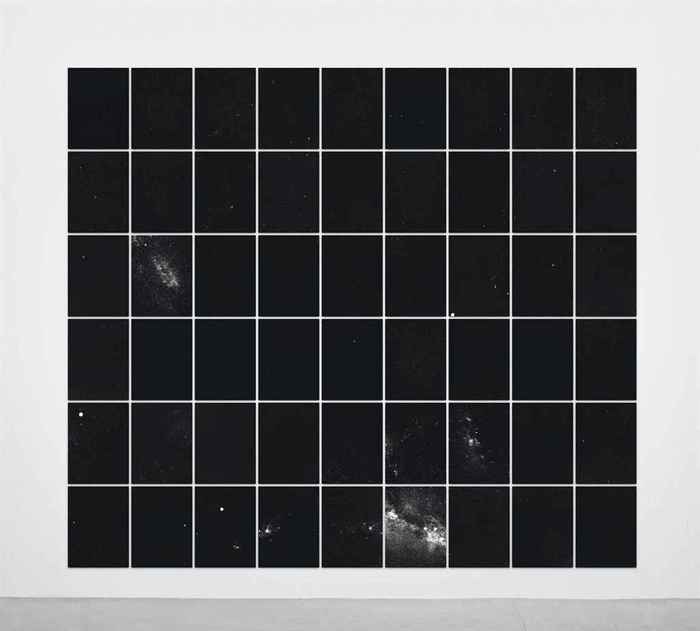

The fact is, what he created was a dubious hybrid, neither true painting nor unadulterated mechanical photography: the hand-colored photographic copy of a hand- painted canvas defied both mediums in one blow. The very originality of painting (in this case, Duchamp’s single most famous painting on canvas) is unsettled in the act of mechanically producing a photographic copy to take its place; yet, conversely, the mechanical reproducibility of photography, the medium’s single most defining feature, is revoked by turning the photograph into a unique, hand painted and–thus newly original–artifact. [p.65]

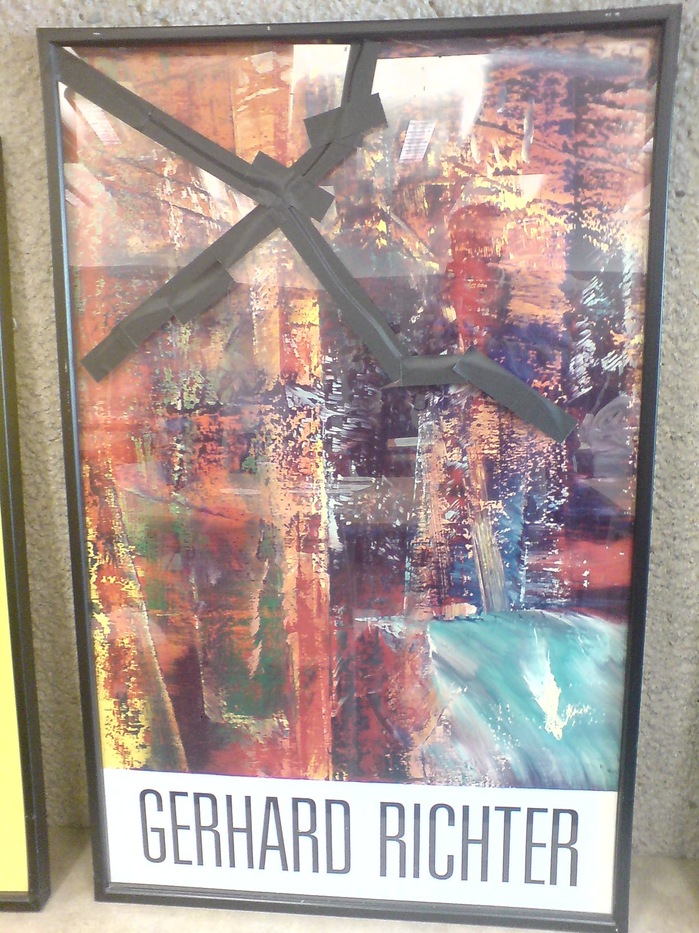

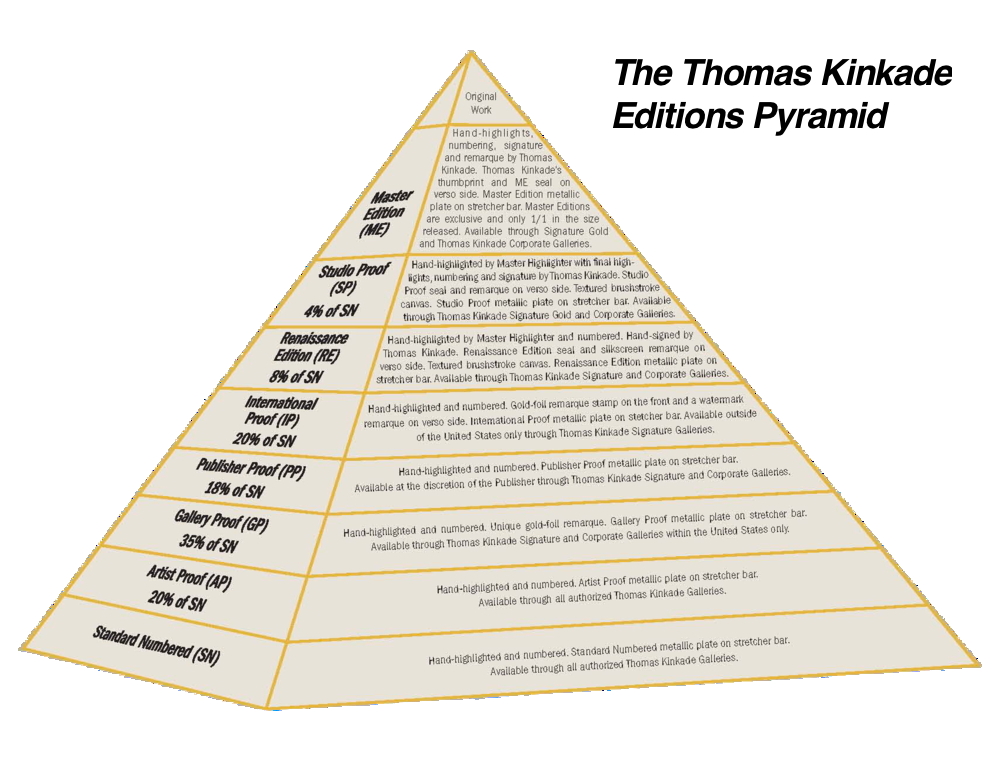

Even better, it’s a photo of postcard of a painting (inspired by photos). A Duchamp Editions Pyramid constructed several generations before Thomas Kinkade’s. Or Gerhard Richter’s. What else will the ever-shifting sands of Art History reveal?

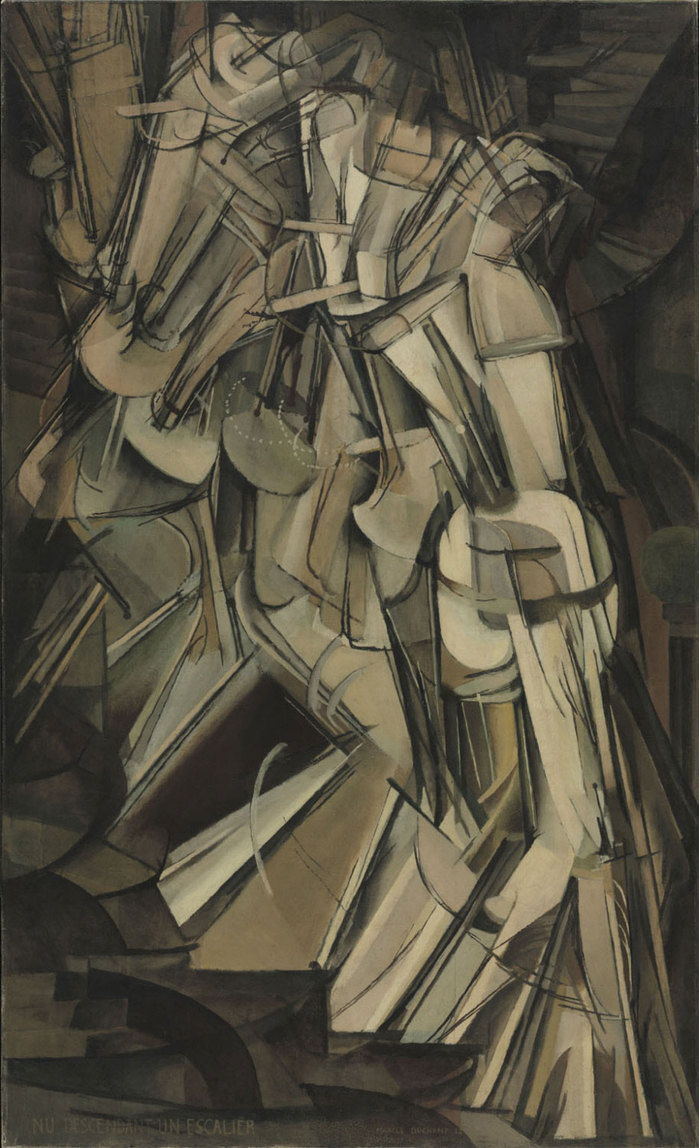

Postcard of Nude Descending A Staircase (No. 2), 14 x 9 cm, published for the 1913 Armory Show, image: aaa.si.edu

The Arensberg’s eventually acquired the original [sic] Nude Descending A Staircase (No. 2) in 1919, and installed both the painting and the overpainted photo in their living room. Then Duchamp showed them side by side in Walter Hopps’ 1963 Pasadena retrospective. Neither is on view at the moment in Philadelphia. Michael Bierke’s great-grandfather sent a copy of this postcard to his wife from the 1913 Armory Show, though-and Francis Naumann is doing his masterwork in the comments.