We’re out of town with family all weekend, so we’ll miss the art fair circuit. Which is too bad because my brother-in-law Benjamin Cottam is showing some work at Volta.

In addition to ‘landscapes’ and ‘blue skies’ paintings [hopefully not the one I called dibs on in his studio a few years ago], there will be some new additions to his various series of tiny–almost trading card-size!–silverpoint portraits. Above, from ‘dead artists’: Andy Warhol, 2002.

Author: greg

Out Of The Bubble

Every time I log in to check my eBay links, I’m like, “Obama!”

See how he embraces John McCain’s strategy for the economy with no pride of authorship?

Did I Say Japanese Internment Camps? I Meant CCC Happy Camps!

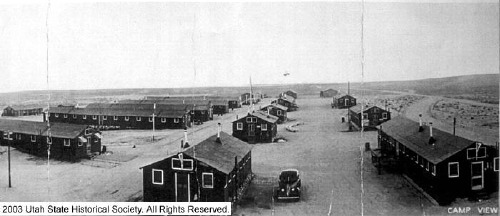

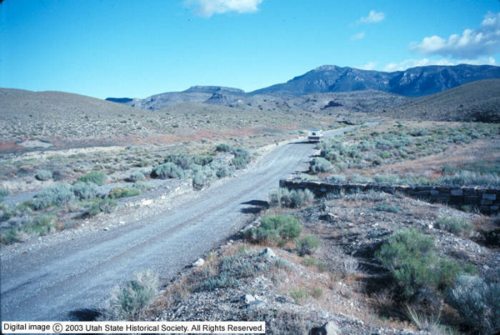

Another thing that caught me off guard looking through piles of photos from the Civilian Conservation Corps, was the camps. My interest in the CCC didn’t come from the New Depression unfolding around us, but from learning over Christmas that while he was in the CCC, my grandfather helped build the Topaz Relocation Center, the Utah internment camp in which Japanese-Americans were interned during WWII.

That Japanese Americans were forced to live in “tar paper-covered shacks” of military design set up in remote, harsh locations is unrefutable evidence of the camps’ punitive, prison-like conditions and an integral element of the entire internment camp narrative.

But what I didn’t realize was that is exactly how participants in the CCC lived, too. The image above, cropped from the official photo of Callao Camp in Juab County, just north of Topaz.

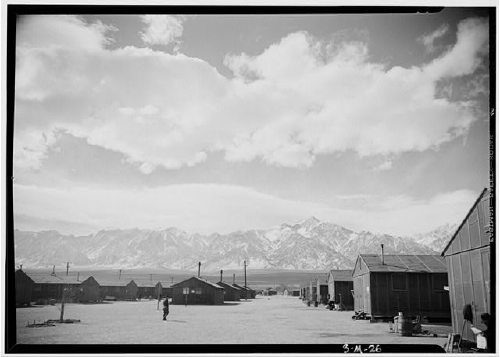

Compare it to Ansel Adams’ photo of the barracks at Manzanar below, from the Library of Congress:

Of course, it doesn’t minimize the injustice of being forced to abandon your home and possessions, then being imprisoned in the desert by your own government because of your race. But–and I know it’s hard to have a “but” after a sentence like that–but I have to imagine that the seven-plus-year history of the CCC, along with the experience of millions of Americans who participated in it, along with the Depression itself, had a formative influence on how the internment camps were perceived at the time.

What would public reaction be today if thousands of Pakistani-Americans were ordered to report to a fenced-off city made of FEMA trailers? Would we be outraged at the outrageous violation of their constitutional and human rights, or would we say, in the wake of Katrina, Ike, and waves of foreclosures, “Hey, what’s the big deal? It’s not a prison”?

Civilian Conservation Corps, AKA The Earthworks Progress Administration

Over the holidays, I taped an interview with my great uncle Wayne. He is my paternal grandfather Champ’s older brother. [Yes, I did ask him about my grandfather’s name. His recollection was that my great grandfather Chester Jehiel Allen hated his own name so much, he was determined to give his kids one monosyllabic name apiece. But that’s not the point right now.]

Wayne told me as a young man growing up in central Utah, my grandfather had worked for the Civilian Conservation Corps. The CCC was one of the most successful Depression-era jobs programs; it put hundreds of thousands of men, mostly from rural areas, to work building roads, dams, bridges and national park fixtures, and doing other construction-type projects.

I’ve been surfing around on the history of the CCC in Utah, trying to get a sense for what his experience was like. From newsletters archived by the Utah State Historical Society, it sounds like it was run in a quasi-military style, with camps and barracks and ranks; it’s hard to imagine my grandfather fitting in well.

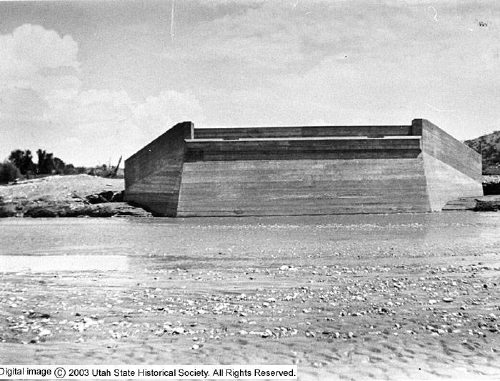

The USHS also has several collections of photographs taken by CCC members, though I couldn’t find any yet from the camps or periods Champ served. The photos show camps or the projects: structures in remote desert landscapes lacking any readily identifiable landmarks. Gabions and walls and foundations of stone in the middle of the desert. Not just bridges to nowhere, but bridges to, from, and in nowhere. Some of them unexpectedly reminded me of Earth Art sculptures.

Ashley A. Workman served in the CCC for seven years, 1934-41, in ten different camps. This undated, unsited photo from his collection of “some type of CCC bridge construction project.” What else could a minimalistic geometric structure, stripped of time, place, context, and utility be but a sculpture? [here’s another view of it.]

We know where Lamar Peterson took this photo, “”Dam on Santa Clara River, Shivcoit Indian Reservation,” [actually, I believe that should be Shivwits, a band of the Paiute tribe] but it still looks like it could be part of Michael Heizer’s City.

I have no idea what Heizer, Robert Smithson, Walter deMaria, or any other earthworks artists thought or said about projects like the CCC’s. Maybe nothing at all, ever. We see these historical works from the other end of the temporal telescope now, but did they look different to people encountering them for the first time in the 1960’s and 70’s?

When these artists began conceiving massive sculptural interventions in the remotest desert landscapes they could find, the country was only a generation removed from the Depression. I expect there was a much greater general cultural awareness of the CCC and its built legacy. And then there’s the post-war construction and baby boom that saw American families taking cross-country roadtrips to national parks via new interstate highways.

If anyone’s seen Earthworks discussed well from this historical and aesthetic context, I’d love to know about it. And if anyone’s then looked even further back, with contemporized eyes, to explore the production of pre-minimalist and pre-Earthwork objects, I’d definitely love to know about it, too.

Images 2 of 1455 CCC photos in the Utah State Historical Society Collection [lib.utah.edu]

The Ur-Grey Gardens

I discovered the Maysles brothers’ 1975 documentary Grey Gardens in my first semester of busines school. My marketing professor showed us Salesman, and it floored me, leaving me to track down the rest of the Maysles’ work.

So I can’t believe that it’s taken me this long to finally read Gail Sheehy’s 1972 New York article on Grey Gardens and the Edie Beales. I wish I’d found it when I was living in East Hampton; would’ve made those winter nights that much crazier.

scan: The Secret of Grey Gardens, by Gail Sheehy [grey gardens news (!!) via choire]

Shoulda Caillebotte It When They Had The Chance

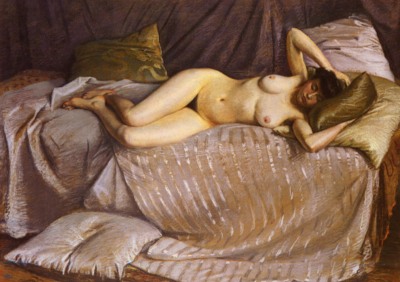

The Metropolitan Museum will get its first painting by Gustave Caillebotte, courtesy of collector/patron Iris Cantor, who made a promised gift of the painting, Femme nue étendue sur un divan, “as a tribute to former museum director Philippe de Montebello.”

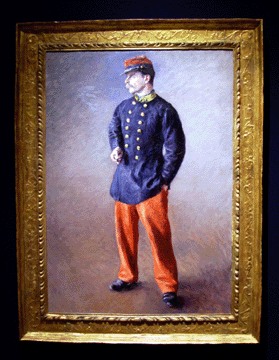

Who was the guy who let their last Caillebotte get away. The museum had been showing Caillebotte’s Un Soldat [above] from 1983 until 2002, when the actual owner, Sam Josefowitz, the Swiss book & record club magnate whose son Paul publishes Apollo magazine, sold it at Christie’s for $6.4 million.

While Femme nue has its undeniable charms, multiple viewings of it as an impressionable art history student didn’t make me want a pair of red pants. The vintage military jacket, on the other hand, was Adam Ant’s fault.

Holy Smokes, New Yorker Films Is Closed

I can’t believe it. New Yorker Films is closing after 43 years in the independent and foreign film distribution business. In the business? They were the business for decades.

When I was working the projection booth at International Cinema at BYU, it was New Yorker’s library I was soaking in. When I moved to New York, it was Dan Talbot’s Lincoln Plaza Theater [and the Angelika, which I discovered on its inaugural weekend during a senior year road trip] where I saw most everything since.

New Yorker was sold to Madstone Films in 2002, and that company pledged New Yorker’s library as collateral and then defaulted on the loan. The creditor, which may be Technicolor, initiated foreclosure proceedings last week. For the sake of the 500+ classic title library, at least, I hope it’ll get acquired by someone who knows Ozu from Oshima. For the sake of Dan Talbot and his colleagues, I can only hope for a soft landing and many thanks.

End of the Road for New Yorker Films [indiewire]

Ely Kim

High Five To The Warhol Foundation Arts Writers

Awesome, I just read through the announcement of the 2008 Arts Writers Grant recipients, and I have to give a huge shoutout to Paddy Johnson whose Art Fag City is one of the first two blogs to be recognized by Creative Capital and the Warhol Foundation [the other is Guerrilla Glass, a “post-glass art” blog project by Anjali Srinivasan and Yuka Otani.]

The Arts Writers program has danced around the new media for three grant cycles now, but this is the first time their solicitation explicitly mentioned blogs. Needless to say, it’s about time, and Paddy’s project is highly deserving and should lend the Arts Writers program some nice publicity and online cred.

Which is ironic, since the reason I applied for a grant last cycle was to leverage CC’s and the Warhol Foundation’s credibility for what would otherwise have to be seen as a cockamamie scheme. I had proposed a blog about the art history of satelloons. The idea was to consider NASA’s Project Echo inflatable satellites–instantly obsolete but spectacularly beautiful mylar spheres which were visible to the naked eye–as an exhibition, a propagandistic and aesthetic exercise akin to the US government’s better-known Cold War-era promotion of Abstract Expressionism abroad.

That would give me the impetus to research and document the development and history of the satelloons from primary source material. But it would also be a stepping-off point to explore the history of art and politics in the Space Age, Pop and Minimalist contexts; the history of art and technology collaborations, including the artists who worked with Bell Labs, a key Project Echo participant. [I especially wanted to see if I could trace the use of mylar balloons from Project Echo through Bell Labs’ black box to Andy Warhol.] By looking at scientifically driven production from an art world vantage point, the satelloon blog would question the defining premises of art, especially intentionality and the aesthetic experience of the viewer. It’s all stuff I will probably pursue here with slightly less urgency over the next year or so.

Just as it was reassuring to see Paddy’s excellent writing recognized, it made me feel slightly less marginal that at least two other grant recipients have projects that resonate with my satelloon idea, if not quite overlap. Art historian Douglas Kahn was awarded a grant for Arts of the Spectrum: In the Nature of Electromagnetism, a book about an intriguing vein of art&science interplay. And Annette Leddy, from the Getty Institute, is writing an article on Robert Watts’ “Space Age Home,” an artist in the 1960’s who apparently “extensively re-imagined the home, its furnishings, and its gardens in terms of an ironic Space Age aesthetic.” No idea, but it sounds like the future to me. Or at least the history of the future.

see the full list of Arts Writer grant recipients and their projects [artswriters.org]

Wait, When Exactly Did Ken Johnson Become Hilton Kramer?

[via]

[via]

Or was it Blake Gopnik? Because Johnson’s review titled “From China, Iraq and Beyond, but Is It Art?” of the New Museum’s current show is so embarrassingly obtuse, it could almost be in the Washington Post.

At first, I assumed the headline was a fluke, the flip result of a lazy copy editor falling back on the most overrated, anti-intellectual straw man of the last hundred years of art world production.

And I was wrong. It’s the core of Johnson’s argument. The show, which I haven’t seen, is a series of works commissioned by three contemporary art museums–the New Museum, the MCA in Chicago, and the Hammer Museum in LA–under the Deutsche Bank-sponsored rubric of The Three M Project.

Here’s how it starts:

In recent years, museums have been getting into commissioning artists to create new works. It is a controversial practice. Some critics think that museums have enough to do just sorting out what already exists. Curators may argue that they are in the best position to identify promising artists and to make possible the creation of important works that might otherwise never be realized.

The problem is that you cannot know for sure what you’re going to get.

Johnson’s premise, false on its face, isn’t even the worst of it. Is he referring to any kind of site-specific installation or work created by an artist for a museum? Does Dan Flavin’s rotunda-filling installation that reopened the Guggenheim count? Siah Armajani’s bridge to the Walker Center? Calder’s mobile in the National Gallery? SFMoMA et al’s sponsorship of Christian Marclay’s Video Quartet? More than half of MoMA’s longrunning Projects series? I’m literally pulling examples out of the air right now. But in ten seconds, it feels like I’ve disproved Johnson’s claims of “recent” and “controversial,” and shown that the odds of “what you’re going to get” are not that terrible.

Again, having not seen the show, I have no opinion on the works myself. If Johnson’s point was that the works commissioned and seen there were bad, and that museums should leave the commissioning to corporations and collectors who know these things much better, that’d be fine. Idiotic and still demonstrably wrong, but fine. Instead, Johnson pulls out the big guns, the art critic’s WMD: saying that something is “not art.”

Of an installation about Urban China, a magazine edited by Jiang Jun which was included in the last Documenta, and which has been praised as “visionary” and which revolutionizes the perception of urbanism in China [a redundancy if ever there was one] through its innovative use of “raw graphic power”, Johnson sniffs: “All this is mildly informative but superficial. You won’t gain any very deep or revelatory insights about Chinese modernity. It isn’t really art, after all; it’s more like an overblown advertisement for the magazine.” [emphasis added on the wtf parts.]

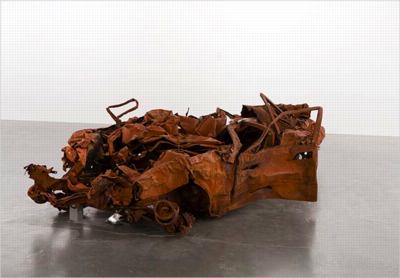

But the biggest critical bomb gets dropped, ironically, on the project by Turner Prize-winning artist Jeremy Deller, in which a stream of “guest experts” on the Iraq war–including veterans and Iraqis–are hosted in the gallery, which also contains the wreckage of car destroyed by a roadside bomb, to discuss their areas of expertise with museum visitors.

What Mr. Deller is doing may be useful therapy for our national post-traumatic stress. Is it art? You can call it an exercise in Relational Aesthetics, the conceptual art movement that takes social interaction as its medium and sociability as its goal. Otherwise there is no way to make any critical or evaluative judgment about it in artistic terms.

Mr. Deller’s project is not nothing. Its potential for doing good and raising consciousness is great. If it isn’t art, that is not a bad thing. It is what it is, as the title says, and what it is is an educational program. To call it art is to pretend it is something it isn’t.

I don’t even know where to begin. Maybe I should feel sorry for Mr. Deller, who has clearly been misled by scurrilous legions of museum no-goodniks to think about something as irrelevant as the experience of visitors to his exhibition, and what they might take away from encountering his work. If only he’d painstakingly recreated that burned out car in fiberglass; if only he’d depicted the disasters of war in a series of aquatints, or perhaps a nice, moody painting; if only he’d interviewed his “experts” on camera, so he could project their giant, talking heads on the wall, or put them on a bunch of televisions in front of a bunch of chairs; or maybe he should have instructed his experts to read something, anything, maybe see if they can count to a million. He might have been onto something.

As for Mr. Johnson, I would suggest that if you’re an art critic who finds himself with “no way to make any critical or evaluative judgment” about a work by an artist awarded his country’s top art prize by its top art museum, which was commissioned and shown by three museums, which is compared to one of the most prominent art movements of the last fifteen years, a movement which was just the subject of a giant exhibition at another not insignificant museum in town, you might consider finding another beat.

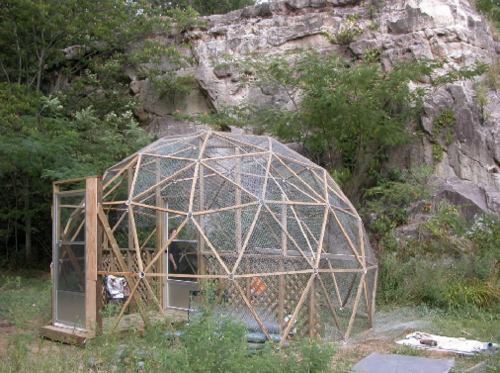

Cave House Proves There Is Something Like A Dome

So naturally, I was intrigued by the folks in Festus, Missouri, who are forced, by their inability to refinance the note on Caveland, the 15,000-sf sandstone cave they spent five years and all their money and time transforming from an abandoned roller rink/concert venue into a house, and so have listed it on eBay. [via]

And I don’t know where Festus is, but maybe it’d be a nice place to get away to? Doesn’t TWA have a hub in St. Louis? Even though it’s double the price of most every other listing in town, $300,000 still seems like a bargain. I mean did Ike and Tina and Bob Seger play in your cave house?

And then I see this big open space in front of the cave, a box canyon, and I think, “You know, that looks like a nice place to put down one of them Buckminster Fuller Fly’s Eye domes…”

So imagine my [non] surprise to find a GeoDome listed first among the Caveland owner’s plans. :

Long enamored with geodesic domes, we envisioned starting with one multi-purpose dome in front of the cave, and later adding a second to separate our office from our living space. We looked at the cave as primarily recreational space and office expansion, with a few commercial possibilities retaining potential.

The evolution from GeoDome to Guinea Dome will be a familiar one to anyone who has endured the never-ending argument between his big dreams and his budget.

A Serra Named Bellamy

11/09 UPDATE: Or not. Writing about her visit to the stored Serra for the journal Afterall, Mary Walling Blackburn reports that it is not Bellamy after all. Bellamy is currently in England. There is, in fact, an I-beam on-site spray-painted “Bellamy,” [visible in Nathan’s photos below], but that is apparently not a nametag or some such. [In fact, the beams are used for stabilizing the pieces during transport. They can be seen in use in Art21’s series of installation photos for Joe at the Pulitzer Foundation in St. Louis.] So that begs the question: what Torqued Spiral is it, then? Inquiring minds might want to ask the artist next time they see him. I know I will.

The story of the Richard Serra sculptures stored along the Bronx waterfront is filling out, thanks to Nathan Kensinger, who went with Jake “The Dobster” Dobkin on their recent photoblogging expedition. A couple of highlights:

- Now we know which torqued spiral

ellipsethis is: Bellamy, named after Serra’s late friend and early dealer, Richard Bellamy. Bellamy founded the Green Gallery, though he only started showing Serra’s work in the late 1960’s after the gallery closed. Bellamy passed away in 1998, just as Serra had begun making his torqued ellipse and spiral sculptures. - Apparently, there’s a nameplate welded inside the sculpture. Can’t say I’ve noticed that before.

- Turns out we’d seen Bellamy before, at Gagosian in 2002 and the Venice Biennale in 2001. Considering we had to walk to the end of the Arsenale in the August heat, and then brave a horrible Vanessa Beecroft installation to see it, Nathan and Jake’s Port Morris fencehopping adventure doesn’t sound all that rough anymore.

- And the biggest piece of news from Nathan’s post, is that the Serras parked there are Serra’s. Which, given the storer’s acknowledged love of rust and industrial grit, and now knowing the personal resonance of the particular sculpture, seems obvious. Or maybe not so much.

Anyway, Nathan’s got much more to reveal, and some sweet photos to accompany it. Previously: Serra from the block

Art & Fear by Bayles & Orland

Whether it’s right or not, this book sounds fantastic:

Making art provides uncomfortably accurate feedback about the gap that inevitably exists between what you intended to do, and what you did. In fact, if artmaking did not tell you (the maker) so enormously much about yourself, then making art that matters to you would be impossible. To all viewers but yourself, what matters is the product; the finished artwork. To you, and you alone, what matters is the process: the experience of shaping that artwork.

Art & Fear, by Peter Bayles and Ted Orland [via kottke and kk]

“Calder on the Roof”

In 1967 Henry Geldzahler, while lecturing the Women’s Group at the Grand Rapids Art Museum, suggested to Mrs LeVant Mulnix III that the city might do well to install a public sculpture on the plaza in front of city and county buildings being designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. Mrs Mulnix promptly wrote to Congressman Gerald Ford to ask for assistance in obtaining a grant from the newly established National Endowment for the Arts for the commission.

SOM senior partner William Hartmann, who was at that time completing the installation of Picasso’s monumental sculpture in front of the firm’s Chicago Civic Center, came in to consult on the project. Alexander Calder was chosen, and La Grande Vitesse which sits on Calder Plaza, has been the symbol of the city for decades.

Grand Rapids was the beneficiary of the friendship forged between Calder and Mulnix, and in 1974, the artist made a gift to the city of Calder on the Roof, a giant red, black and white mural executed on the roof of the Kent County Administration Building.

The work was intended to be seen from the surrounding buildings, which basically means the adjacent City Hall. Of course, it looks pretty sweet on Google Maps, too.

Musical Commentary Track

I caught a few minutes of Joss Whedon on Fresh Air yesterday; for the first half of the show, he was talking about the making of Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog, and the awesome-sounding DVD, which includes Commentary! The Musical! the world’s first singing DVD commentary track.

Joss Whedon on Fresh Air, 2/11/2009 [npr.org]

Buy the Dr Horrible DVD at Amazon [amazon]