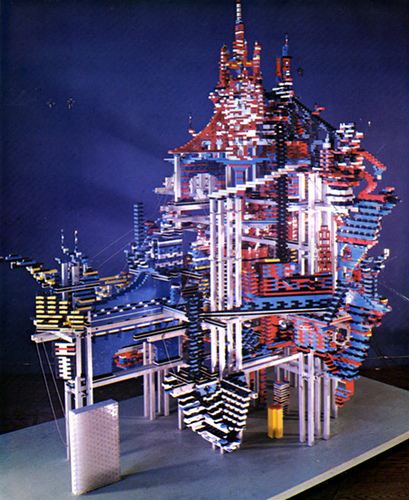

Holy smokes, this is really wonderful. [via fimoculous]

Author: greg

The Codicil To John de Menil’s Will

In 2005, Robert Gober curated a show at the Menil Collection in Houston. In his catalogue, Robert Gober Sculptures and Installations, 1979-2007,” for the Schaulager show, Gober says, “Initially, I was only interested in curating from the collection and not including my own work, but when I began investigating the contents and the storage of the Menil Collection, I saw what [then chief curator] Matthew Drutt was already seeing. My work and the work in the collection shared affinities and themes. Catholicism, Surrealism, race, and a belief in the everyday object.”

The exhibition’s title, “The Meat Wagon,” comes from a codicil to John de Menil’s will. It’s awesome.

To my Executor

c/o Pierre M. Schumberger

I am a religions man deep at heart, in spite of appearances. I want to be buried as a catholic, with gaiety and seriousness.

I want the mass and last rites to be by Father Moubarac, because he is a highly spiritual man. Within what is permissible by catholic rules, and within the discretion of Moubarac, I want whoever feels so inclined to receive communion.

I want to be buried in wood, like the jews. The cheapest wood will be good enough. Any wood will do. I want a green pall, as we had for Jerry MacAgy. I would prefer a pickup or a flat bed truck to the conventional hearse.

I want the service to be held at my parish, St. Annes, not at The Rothko Chapel, because it would set a bad precedent.

I want music. I would like Bob Dylan to perform, and if it isn’t possible, any two or three electric guitars playing softly. I want them to play tunes of Bob Dylan, and to avoid misunderstanding, I have recorded suggestions on the enclosed tape. The first one, Ballad of Hollis Brown is evocative of the knell (nostalgic bell tolling). Then at some point Blowin’ In The Wind, The Times They Are A-Changin’ and WIth God On Our Side, because all my life I’ve been, mind and marrow, on the side of the underdog. Then Girl From The North Country to the rhythm of which the pall bearers would strut out of the church. Father Duploye could also be asked to sing Veni Creator in latin, to the soft accompaniment of a guitar.

I would like the funeral director to be Black.

I would like the pall bearers to be Ladislas Bugner, Francesco, Francois, Miles Glaser, Mickey Leland and Pete Schlumberger.

I would like George to stand with Dominique, Christophe, Adelaide, and Phil. Simone Swan, Helen Winkler, Jean Riboud, Ame Vennema, Rossellini and Howard Barnstone will be part of the family. Also Gladys Simmons and Emma Henderson.

I want no eulogy.

These details are not inspired by a pride, which would be rather vain, because I’ll be a corpse for the meat wagon. I just want to show that faith can be alive.

Date:NovemberDecember 13, 1972

/s/ John de Menil

The Rothko Chapel had only been dedicated in 1971. John de Menil died on June 1, 1973. His wife Dominique, who exerted a formative influence on my views of art in the times we met between 1990 and 1995, died in 1998.

Rain Machine?

Just a Vegas-y two second video, but I wonder if this rain machine gives a hint of what’s coming this week at Olafur Eliasson’s MoMA/PS1 show.

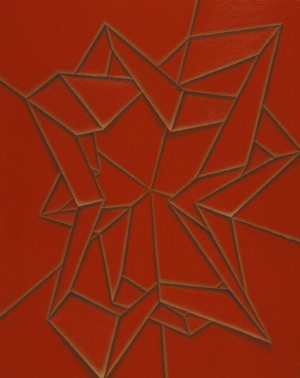

It’s A Little Abstract

Another of the things that Richard Serra said at LACMA last week has stuck with me was the artist’s call to arms for abstraction: basically, for artists in the 20th century, you’re either with us [i.e., Serra and Malevich] or you’re with the terrorists [i.e., Duchamp].

I was reminded by it, ironically, by the Times’ review of the new Tomma Abts show at the New Museum. By now, the spatial effect of seeing Abts’ arduously determined, small-scale, abstract paintings installed in large, white cubes is part of her experience. Abts’ room at the Carnegie International–which was also curated by Laura Hoptman–was an engrossing highlight; the paintings commanded the industrial space at greengrassi in London, too.] Ken Johnson writes, “Ms. Abts’s 14 small works look as though they died and went to heaven.”

But he also said, “Stylistically the paintings seem oddly out of sync with the present; they could be recently rediscovered works from the 1950s or ’60s.” That sense of anachronism seems inextricably tied to both the style–abstraction–and to the size. Though I can think of powerful exceptions, it seems like abstraction and smallness have been out of sync since WWII.

Abstractionist Thomas Nozkowski, who gets namechecked by Johnson–and whose resurgence is happening right now withfirst show after switching from Max Protetch to PaceWildenstein–talked in 2004 of deliberately choosing in the 70’s to paint on small board instead of giant canvas…

You can’t really understand artists of my generation until you factor the political atmosphere into any analysis of their work. I felt that I could no longer do big paintings that were for an audience of the very institutions that I then despised. The last thing I wanted to do was to paint for a museum, to paint for a bank lobby. I wanted to paint paintings that could fit in my friends’ rooms. So I started making 16 by 20 inch paintings that you would recognize today as my work, in 1975. These pictures, initially for political reasons, had roots in subject, in things that connected to the real world.

…and of the extremely skeptical response he received at the time, from curators, dealers, and his fellow artists:

I remember Steingrim Larssen who was then the director of the Louisiana Museum near Copenhagen coming by, and, to my surprise, he got excited about the paintings. This was 1975 or ’76, and he pulled a whole group out, said that he thought they were really interesting and then said, “Your psychiatrist told you to do these right?” He just thought it was some kind of therapy, he couldn’t imagine that this was serious work. I got a lot of that. Even Betty Parsons who was very supportive and loved young artists, she would flinch whenever I showed her a painting. So, I joined a co-op gallery to have a way to get them out of the studio and into the world.

…

There was an organization called The Organization of Independent Artists and they were attempting to subvert the gallery and museum system and all the established hierarchies. They had decided that each artist shown in their group shows would pick the next artists and so on. I was one of the artists chosen for the second show. I remember going to the organizational meeting and being told that the other artists had decided I couldn’t be in the show because the paintings weren’t serious.

Art Of Note

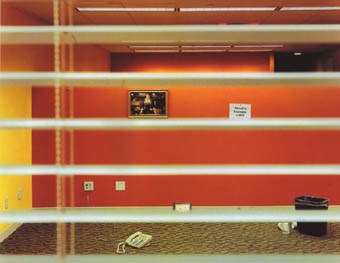

Andy designed this postcard for the Walker Art Center, which is cool.

But the notes on the flickr photo are even cooler.

cf. the most heavily annotated photo on flickr [kottke]

Karl Lagerfeld Has A Posse, Duh

which includes a Diet Coke butler [via andy]

[2023 update: Mr Mort posted these c. 2008 photos on instagram on the occasion of the Met’s Costume Institute show. I remembered blogging about the Diet Coke butler (because ofc), and noticed that the flickr embed code was not working anymore, though the direct link is still active. So I updated the pics, and left the link.]