I was going to call it a guilty pleasure, but entering Souren Melikian’s reality distortion field every weekend is clearly a vice.

Melikian covers the art world for the International Herald Tribune–which, for him, begins and ends at the auction house–and his byline always sits atop the upper right-hand corner of the NYTimes.com Arts page.

Though his topics are tied to the vagaries of the sales calendar–one week it’s Chinese jades in London, another contemporary art, this week it was Old Masters and French landscapes in New York–Melikian’s soaring optimism is untethered by context, history, inconvenient facts, or actual reporting. While he may actually attend some of the sales he covers–he may have his own desk at Drouot, for all I know–he could just as easily be writing about flipping through the Christie’s catalogue. The Pat Kiernan Reads The Morning Papers To You of the art world.

Whatever his technique, though, and no matter how poor Melikian’s subject is always, always the same: the booming market is full of connoisseurs, ready to throw caution to the wind in pursuit of an ever-dwindling inventory of masterpieces. Here’s the setup for today’s column, titled “Old Masters Set Off Intense Bidding”:

Buyers pounced on Old Master paintings this week with a determination that has not been witnessed at auction in a long time.

Two reasons combined to account for what felt at times like a rage to buy. The gloom induced by the recession is slowly receding and awareness that supplies are drying up is spreading fast.

That’s wonderful! Except that the next sentence–and most of the rest of the sales Melikian recounts–completely belie that upbeat thesis. Here’s the next sentence:

The scarcity of goods was actually made painfully obvious at Christie’s on Wednesday. The need to fill their catalogues with a minimum number of lots had apparently persuaded the departmental heads to accept too many second division works and to estimate them at levels more appropriate for gems.

Oh, you mean no good works, unrealistic estimates, and half the lots failing to sell. As for those pouncing bidders: “A single $6 million bid came in and the auctioneer wisely knocked down the Goltzius…” and “Where one might have expected competition to break out, only one hand went up.”

You can literally click on any of his articles and find a hilarious gem, but here are a couple of choice Melikian Musings from last fall’s contemporary sales, which, we were told, “revealed for the first time a deep interest in works on paper”:

The auction market is booming and, when it comes to contemporary art, it is charging on at an accelerated pace, as it did before the financial turmoil broke out in the autumn of 2008.

This week, those attending Christie’s and Sotheby’s evening sessions traditionally reserved for the most important works might have briefly thought that there never was a recession. No awareness of it appeared to linger in the bidders’ minds as they ran up paintings, drawings and sundry three-dimensional works to three times the estimate, or more…

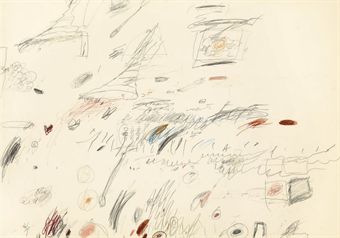

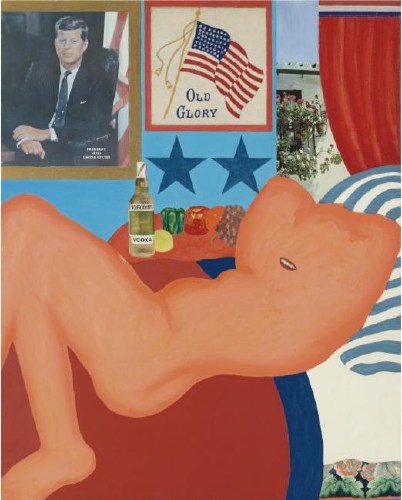

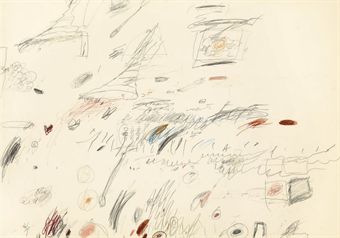

Other large prices paid for works on paper confirmed that a new pattern was emerging. A typical exercise in random scribbling by Cy Twombly made $722,500, nearly double the high estimate. The sketch does not markedly differ from the nascent bouts of creativity of 4-year-olds expressing pencil in hand their joie de vivre. Interestingly, this similarity to early childhood artistic endeavor has no bearing on the price. Visual aesthetics are clearly not among the primary considerations driving contemporary art buyers.

Contemporary art loves you too, Souren. In my mind, I picture Melikian at a Paris salesroom, indistinguishable, in his double-breasted suit, combover, and excruciatingly coordinated tie-and-pocket-square combination, from the affectedly elegant antiquities dealers he’s chatting up. In other words, he embodies the International Herald Tribune of a certain age, the age before the Times gutted it, when the paper still mattered, when it served as the primary news source and the paper of record for a well-heeled, English-speaking, international touristocratic diaspora. No matter how bleak the news from a couple of days ago was, I’m sure Melikian’s perennially sunny shopping outlook held equal appeal for the Tribune’s antique-hunting readers and its antique-peddling advertisers.

So sure, I read him for the pointless outrage, but I also read him for the nostalgia. Just as they aren’t making any new Old Masters, they sure as hell aren’t making any new Souren Melikians.