What a weird, insane s**tstorm is brewing around Brandeis University’s sudden announcement that it’s closing the Rose Art Museum and selling off its 6,000 piece collection. All the usual outrages and condemnations are moved and seconded, of course, but there are some things about this disaster-in-motion that just don’t make any sense:

First up, it’s not at all clear why such a drastic action is even necessary. A $10 million forecast operating deficit is a problem, but it’s not the kind of thing you sell your institution’s soul for. Greg Cook looked at the last three years of Brandeis’s financial statements and found they university was running healthy surpluses.

Obviously, the recent plunge in the financial markets has to have an effect on Brandeis’s endowment, but I haven’t seen any announcement of what the impact was. There has been talk of a Madoff Effect, with several key donors being hit hard by the evaporation of his hedge fund Ponzi scheme. What I haven’t seen is any direct exposure of the Jewish university’s own investments. If Brandeis’s endowment suffered a mortal blow, you’d think word would get out.

But what’s up with this comment to the NY Times from Robert Mnuchin, the former Goldman Sachs partner-turned-dealer, who also happens to be the son of pioneering donors of the Rose, Leon and Harriet Gevirtz-Mnuchin? It was their contemporary acquisitions fund that enabled the young museum to stock up on the works of emerging Pop Art stars in the early 1960’s, paintings which Mnuchin fils is now trying to get a piece of:

[Mnuchin] said he had no idea of Brandeis’s plans until he read about them. “It’s such a shame, particularly at this time in the world,” he said, adding, “Obviously as a dealer I’d like to be involved either in buying them or selling them. It’s emotional for me.”

So a dealer eager to broker his parents’ legacy, and this, the history of the Rose from the museum’s website, what is up with this? It’s just odd. Have you ever seen a museum give a chattier, tackier account of its own story, including discussion of what a great deal they got, and how much their stuff is worth now?

A miracle of another kind also occurred during a four month period in 1962 and into 1963. As Hunter describes it, “Leon Mnuchin called from New York one day to announce that he and his wife, Harriet Gevirtz-Mnuchin had inherited a sum of $50,000, with which they wished to fund a contemporary art collection at Brandeis.”With what has happened in the art market since, that’s like Bill and Melinda Gates calling one day and saying they have $150,000,000 to start a contemporary art collection!

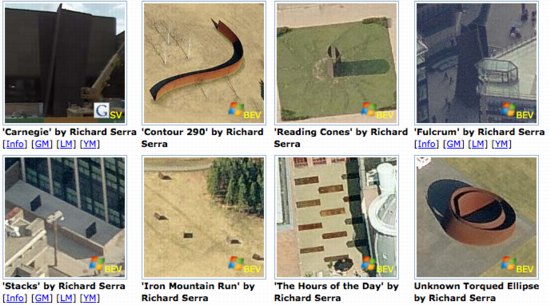

Hunter reports that he and “Leon immediately set out to explore the galleries. We often made gallery rounds with Robert Scull, a friend of Leon’s and a prominent New York collector,” especially of Pop Art. During their rounds (which included studio visits during which they bought directly from artists) they managed to gather early and important works by Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, Jim Dine, Tom Wesselman, James Rosenquist, Adolph Gottlieb, Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, Morris Louis, among many others. Their limit was $5,000 a painting (which meant several were bought for much less). Warhol had already become a bit expensive, Hunter says, so they went for one of his lesser works from the “paint-by-number series.” If the term “miracle” may be evoked for a third time, a couple of years later, Hunter’s successor at the Rose, William Seitz, exchanged that Warhol (Do It Yourself Sailboat, 1962) , for Saturday Disaster, 1964. Collectively, at this writing, the Gevirtz-Mnuchin collection along with the Warhol, are worth in excess of $200,000,000

It is important to remember that Hunter and Mnuchin went in search of art, not market value…

Mmhmm. What were you saying? You lost me at “paid $5,000, now worth $200 million.” Turns out that’s not the woman next to you who talked your ear off the entire flight to Palm Beach. The history’s by the current director, and it appears to be a speech transcript, from a celebration, ironically, in advance of the Rose’s 50th anniversary in 2011.