We’re the dog.

Lutz Bacher, June-Sept 2017 [cushionworks.info]

Lutz Bacher dot com [lutzbacher]

the making of, by greg allen

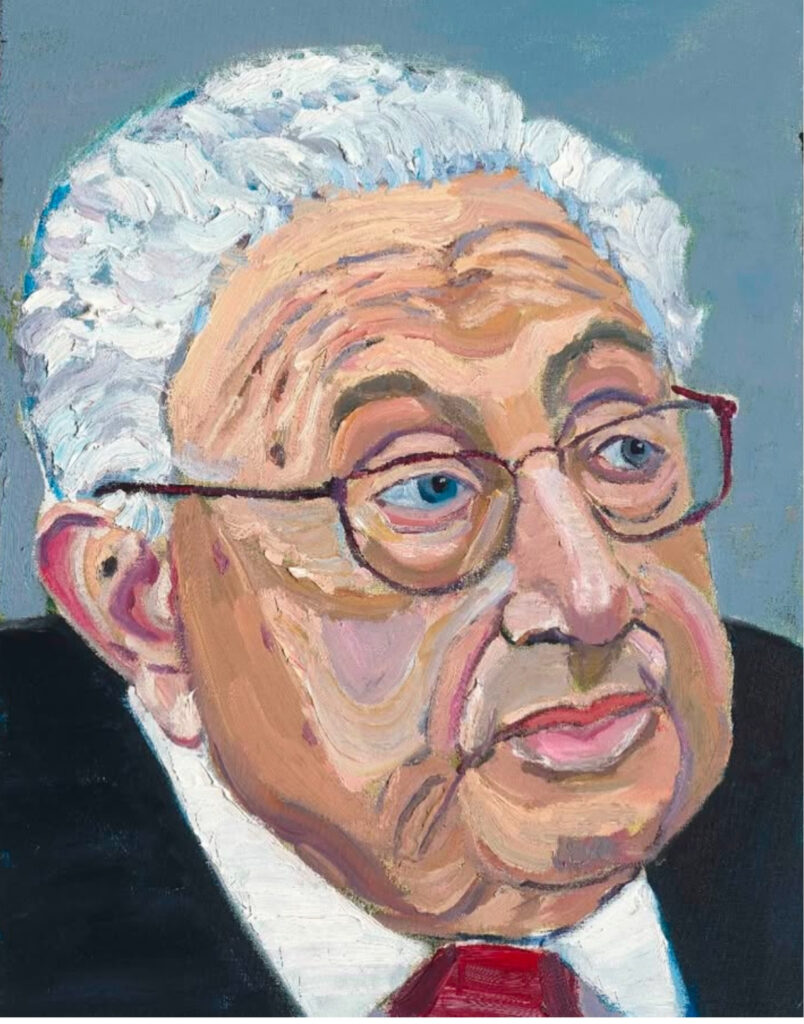

At the beginning of the first Trump administration, I began a project to capture moments of historic significance “in the manner of the most relevant painter of the age, George W. Bush.” Well, that project got gigantic and depressing as hell very fast.

But nothing in the intervening years has changed my view, though, of George W. Bush, who, in addition to giving us this Supreme Court, remains the most relevant painter of our age.

I was not surprised, neither was I pleased—it’s not the kind of thing you can take much comfort in—to learn via Chris Rusak, that Bluesky art critic @dickius.bsky.social shared the same view.

Responding to a prompt for a painting of the age, dickius skeeted, “This painting by G. Walker Bush. It really captures an era defined by the worst people on earth getting away with their crimes — indeed, being rewarded for them.”

In February 2020, weeks after Biden’s inauguration, I went to see Bush’s paintings in person at the Kennedy Center. I wondered then about whether the world would be better off with more paintings like this in it. Today, I can’t imagine a better fit.

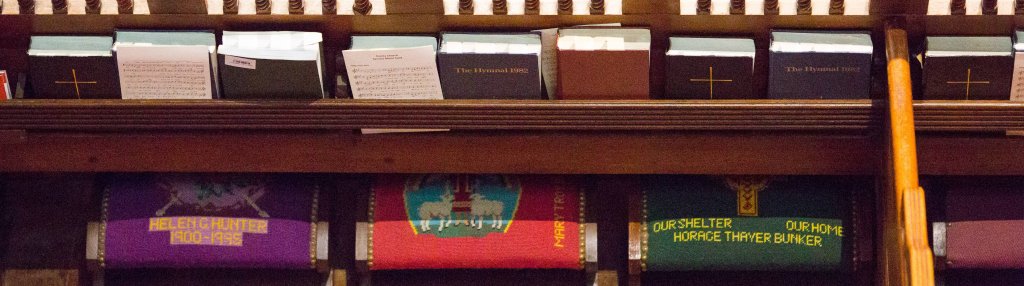

Really, all it took was seeing the sonorous phrase—needlepoint kneelers—and I believed. It was on the cover of a privately published history of a parish’s longstanding ecclesiastical needlework program, which fashion prophet Rachel Tashjian-Wise revealed on a post while visiting family over the Christmas holidays.

Growing up near, even friendly with, but not in commune with the Episcopal Church, I was fascinated to find an entire world–or rather, a very specific and highly developed part of the world I’d previously never knew or imagined—of ecclesiastical needlework. It brings together faith and devotion, but also memory, community building, philanthropy, gender, class, and history, and that’s even before it gets to craft, technique, design, and the material. And it all plays out within the ecclesiastical, managerial, and social structures of the Church.

Basically, parishioners of a church donate time, talent, and resources, to creating handmade needlepoint cushion covers for the kneelers that line the pews of the church. In one place it may be the historic legacy of a dedicated crowdsourcing effort to beautify a new or rebuilt church, or a lifelong effort to memorialize someone. In another it could be a highly organized and socially prestigious fundraising activity. As with any such laborious handwork, needlepoint kneelers seem historically likely to reflect the value of the role, time, and taste of women in the community. It could be a sign of sacrifice or extreme privilege. [cf. prolific needlepointer HM ex-Queen Margrethe II of Denmark]

In the UK, needlepoint kneelers were apparently under threat, a dying art, according to someone who wrote a book about them. Things seem better in the US, a phrase I imagine I’ll be saying less and less going forward. It turns out our [sic] Episcopal church, the National Cathedral, has a needlework kneeler program.

And an epic post on the National Altar Guild Association’s blog about starting and operating a successful program feels like needlepoint kneelers, as an institution, remain sound. Besides the amazing new (to me) vocab, every observation or piece of advice from Bid Drake, “internationally known ecclesiastical needlepoint specialist [and] author of the Guide to Church Needlepoint Care and Maintenance” feels hard-won from direct experience: “I strongly suggest that you invite everyone in the congregation to help make the kneelers, then teach them Basketweave on small useful pieces like Chrismons, usher tabs, and collection plate silencers.” “If you only give out a third of the yarn with the canvas and tell the stitchers to take their pieces to the ‘Mistress of the Yarns’ when they need more, you will have an instant check on which pieces are being stitched, and which are buried in closets.” “Your local needlework shop should be able to suggest a finisher — one who loves and respects needlepoint, not an upholster who treats $4,000/yard needlepoint like $10 chintz.” [oof]

There’s so much about this cultural dynamic that fascinates me, and how it results in these highly specific objects. I’ve looked in the past without success for scholarly consideration of similar craft- and gender- and class-coded objects; who’d have thought that what was missing in my ersatz needlepoint history project was God. 🙏

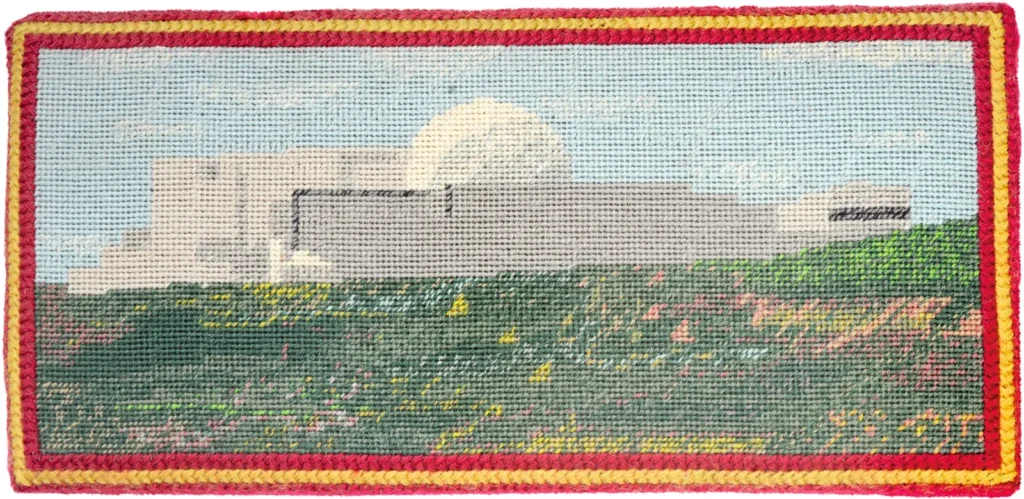

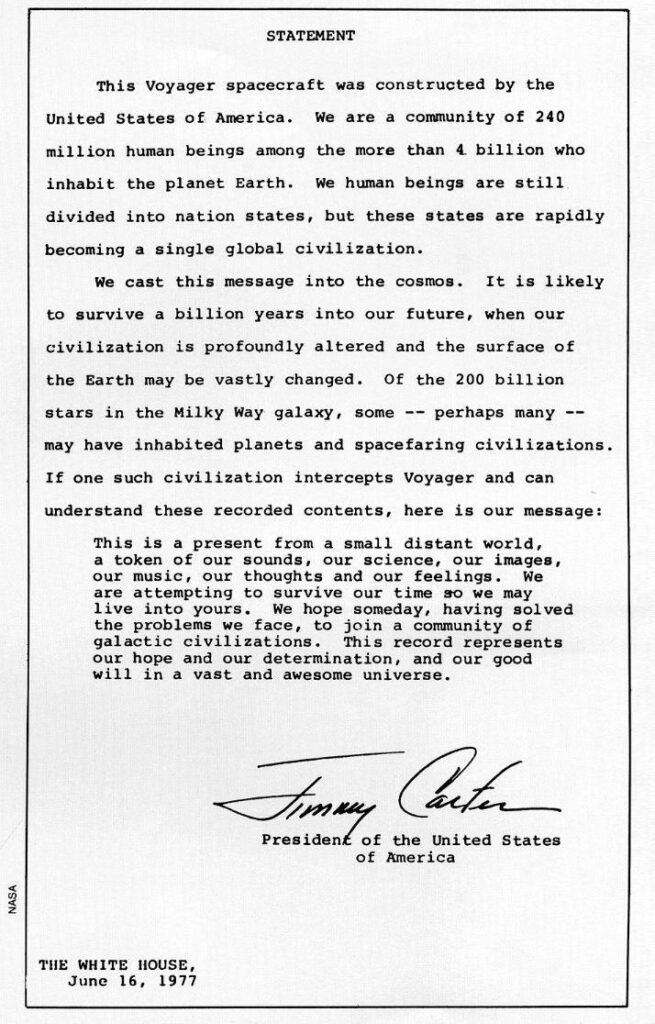

President Jimmy Carter’s 1977 statement to the cosmos, above, was encoded as an image, like a photostat, on the Golden Record attached to the Voyager space probes. A similar statement image was included from Kurt Waldheim, then secretary general of the United Nations.

For whatever reason, neither image is included in the lists of 115 or 116 images that Carl Sagan and his committee selected for the Golden Record. According to Wikipedia, these are the 117th and 118th images on the record.

This Voyager spacecraft was constructed by the United States of America. We are a community of 240 million human beings among the more than 4 billion who inhabit the planet Earth. We human beings are still divided into nation states, but these states are rapidly becoming a single global civilization.

We cast this message into the cosmos. It is likely to survive a billion years into our future, when our civilization is profoundly altered and the surface of the Earth may be vastly changed. Of the 200 billion stars in the Milky Way galaxy, some–perhaps many–may have inhabited planets and spacefaring civilizations. If one such civilization intercepts Voyager and can understand these recorded contents, here is our message:

This is a present from a small distant world, a token of our sounds, our science, our images, our music, our thoughts, and our feelings. We are attempting to survive our time so we may live into yours. We hope someday, having solved the problems we face, to join a community of galactic civilizations. This record represents our hope and our determination, and our good will in a vast and awesome universe.

RIP, President Carter

previously: Off The Golden Record

On The Golden Record [on decoding the images, from 2015]

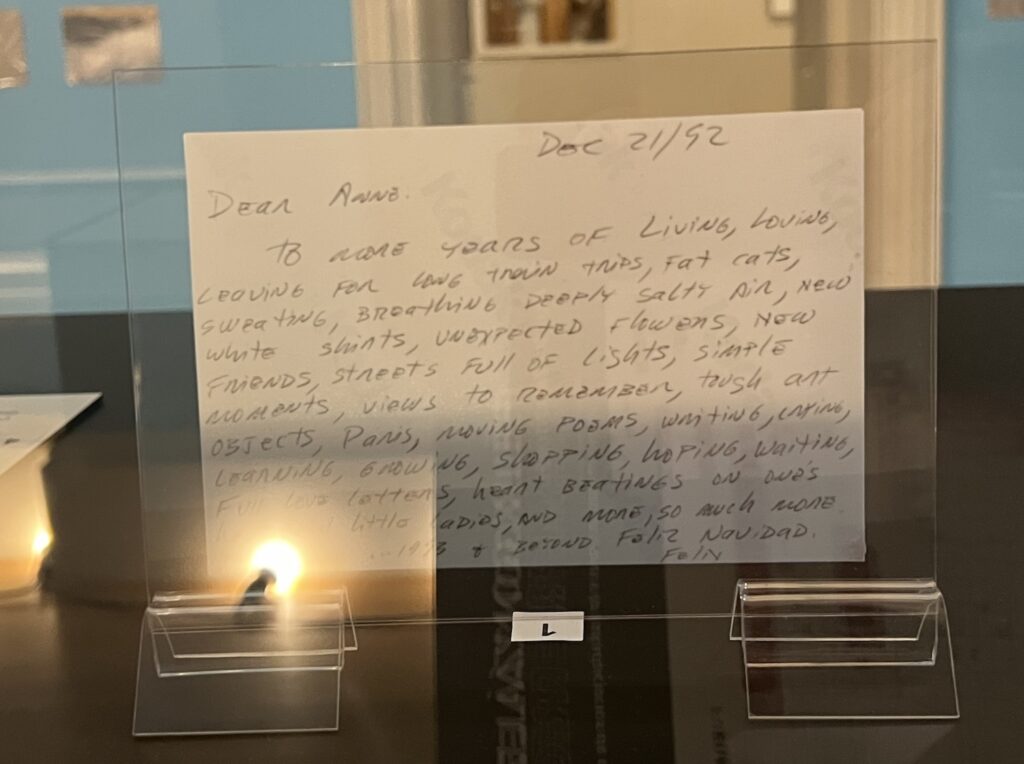

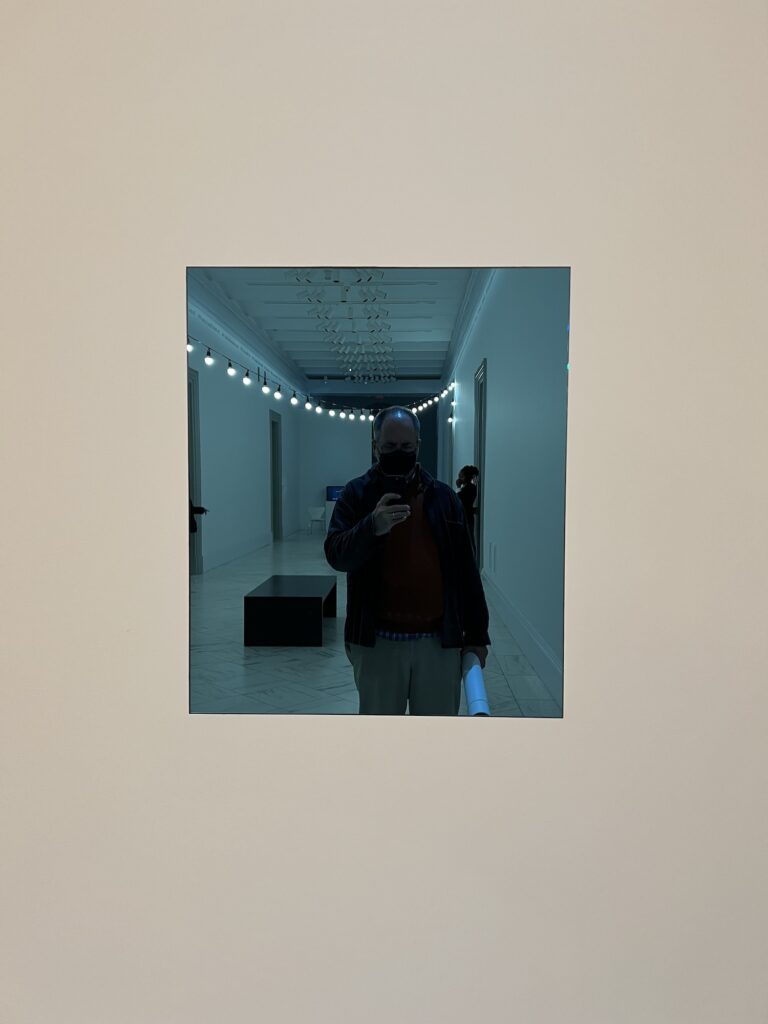

I had wanted to post this snapshot Christmas card Felix Gonzalez-Torres sent to MoMA curator Anne Umland again on the date he wrote on the card, December 21, but I missed it. So I am posting it on the day I imagine he posted it.

Previously, related: Felix Navidad Exhibition Copy

Felix Gonzalez-Torres @ NPG

Alex Greenberger not only has a review of Glenstone’s Cady Noland exhibition, he breaks news about it. And he not only breaks news about it, HE HAS PICTURES. Run, click, don’t walk. I’ll wait.

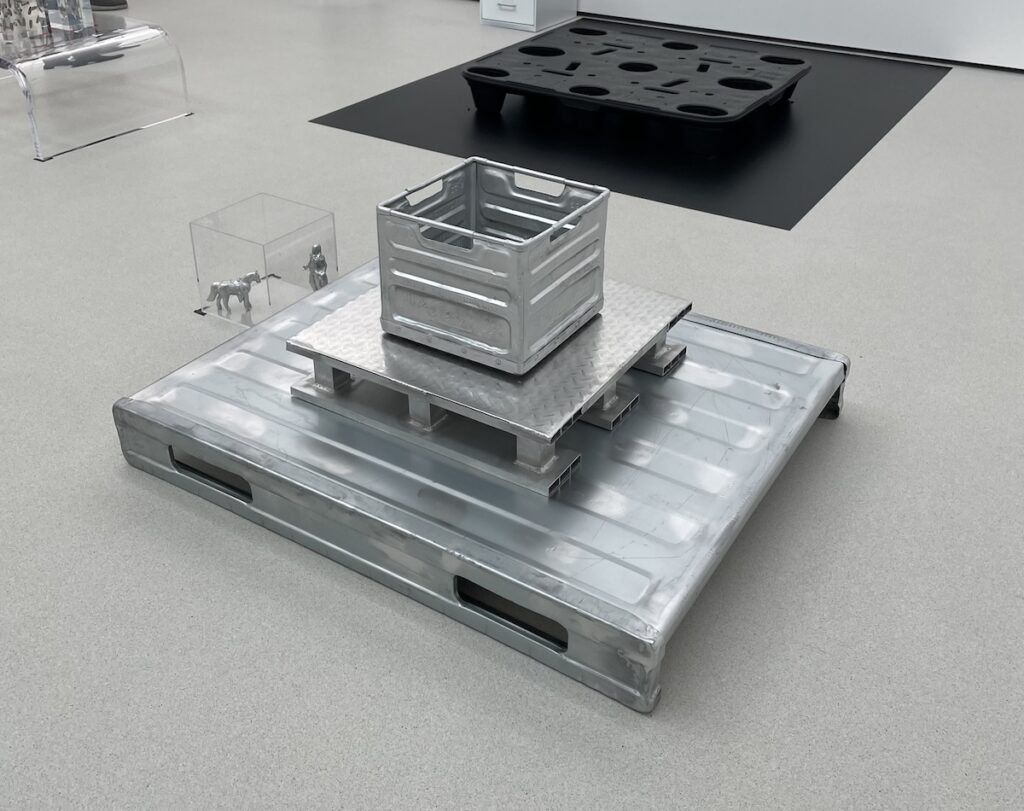

OK, while I think he’s kind of overinterpreted the transgressive unavailability of those black palettes Noland has added to the room otherwise filled by the contents of the artist’s Gagosian show last year, Greenberger is right to notice the slipperiness of the exhibition checklist. There are objects that are on the map, but not on the works list. The stacked palettes are an “element” in this category, and so is another stack of aluminum objects—which turns out to be a 2024 work “on loan” from the artist [scare quotes in the original].

It’s been almost three weeks, and they have not “corrected” their information, and the Glenstone folks get a little coy when Greenberger asks if they will. Now Glenstone is a professionally run and thoughtful institution where the impact of subtle detail is not unappreciated. This incompleteness, this inaccuracy, is part of the encounter; this disconnect between what you see and what you’re told is part of the experience.

[December 2024 update: they have added the loaned work to the checklist. It is “‘Untitled’ 2024, metal crate, metal palettes, courtesy the artist and Gagosian.”]

![clip-on man is a 1989 work by cady noland depicting a cropped photo of a wild drunk middle aged white guy in a dark suit with empty six pack rings clipped to his belt, a beer in his hand, and one left dangling in front of his crotch. the image is screenprinted in black on an aluminum panel, while a grid like a flimsy set of strainer bars sticks out on the right side, roughly forming a square. the work sits on a wood floor and leans against a white wall. the pic is via gagosian but the work is currently on loan from the artist [shhhh] to glenstone. the photo is by a guy named charles gatewood; he took it at mardi gras in the early 70s](https://greg.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/noland-clip-on-man-beachpkg-gagosian.jpg)

Let me add another piece of info in turn, which I don’t know whether to believe myself, but that fits: Clip-On Man, the 1989 work at the pavilions’ entrance, listed as being from a “private collection,” is also a loan from the artist.

In 2017, Beach Packaging Design blogged about Clip-On Man and the source of Noland’s deranged image: Sidetripping, a gonzo street photography book by Charles Gatewood, with a text hustled from William Burroughs, published in 1975 [hey, the same year as that Joan Didion speech!]

I read Sidetripping at Glenstone last time I was there, sitting on Martin Puryear’s elegant bench, facing a tastefully manicured wilderness. Gatewood revels in the underbelly of New Orleans as a degraded destination of American freakdom. Burroughs’ text is a highly baked, freeform riff on the photos, which Gatewood put in front of him while working on assignment for Rolling Stone. In subject, luridness, and bleakness, it felt like a touchstone for Noland’s entire project, if not a straight-up Rosetta Stone. I can see why she’d put that at the entrance of her show. [And name her previous show after it, and her book.]

[NEXT DAY UPDATE: I went back to Glenstone today to see this shiny stack I’d seen before, now disclosed to be a new work from the artist. This Pinkerton’s crate situation is a bit overdetermined, I think. There are actually two similar crates of stamped, galvanized sheet metal in the gallery, each with the name of a different regional dairy, and each threatening the involvement of the Pinkerton’s if you steal it. One looks like this, complete but very vintage. The one Alex says was cast certainly has a pristine finish. It could be sandblasted or remade, for sure. I did find a picture of the previously unacknowledged work on the internet:

That middle pallet is the one with the Amazon ASIN sticker still on it: the Vestil AP-ST-2424-SB, currently listed on AMZN as unavailable, though it can be easily found on other retail sites.

Speaking of Amazon and pallets, that black pallet in the background is of the type also mentioned in Alex’s review. It, too, is findable online, though maybe you need a commercial account to purchase it. I think the “violation of state law” thing is, like the Pinkerton’s warning, a boilerplate assertion of ownership for property that circulates unattended on these mean streets. A cattle brand for corporate assets.

On my way home, I had to return a cursed Amazon purchase, and so made a rare trip to a Whole Foods, where I was greeted by this:

While we wait to hear if these pallets, too, are a previously unacknowledged Cady Noland, we can bring their implication in the monopolistic retail/digital/content behemoth engulfing our world into the unsullied noncommercialism of the Glenstone installation. Also, if, looking back at the Gagosian show it felt like half the non-vintage elements were sourced at The Container Store, remember there is one in Chelsea, right next to a huge Whole Foods. Instead of an artist who has walked away from artmaking, we may have to reimagine Noland as someone making art from the churning world she passes through every day on her way to the gym.

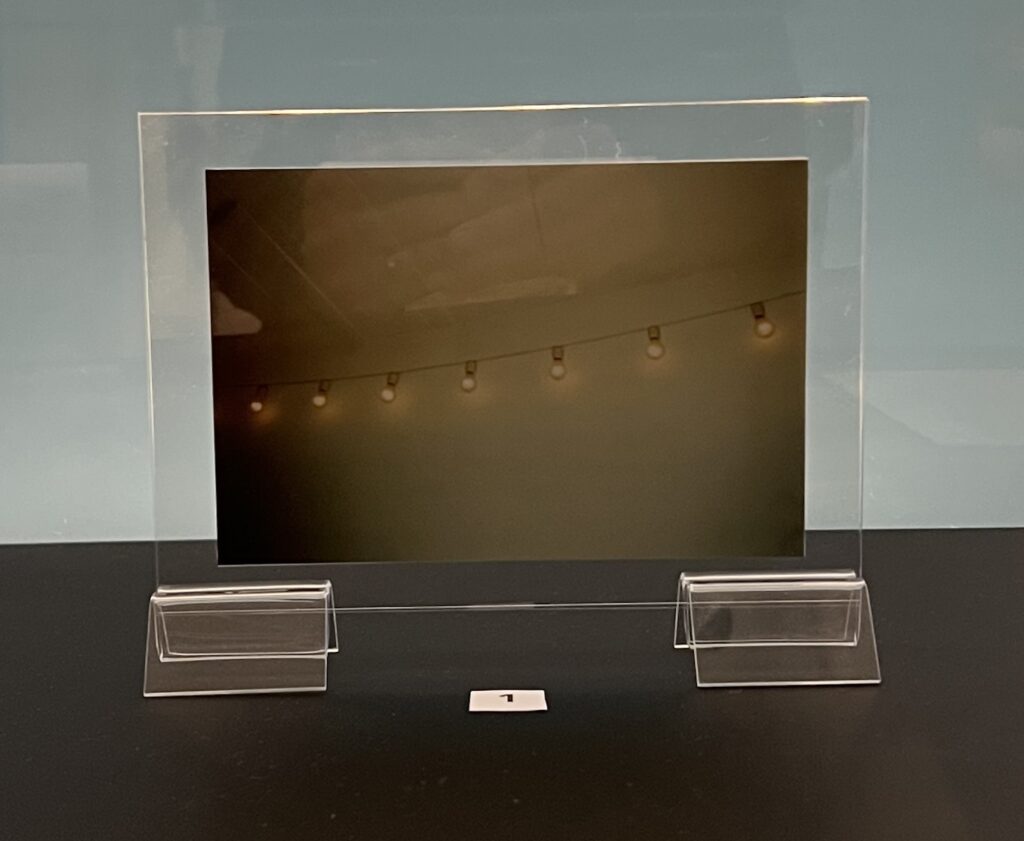

One unexpected thing from the Felix Gonzalez-Torres exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery is the inclusion of a few examples of the artist’s correspondence, the notes and snapshots he regularly sent to friends and colleagues. They’re shown amidst all 55 of the artist’s photo puzzles, which underscores their similarity to the photos and letters Felix used. But only to an extent. By expanding the borders of the pool of imagery and text from which the artworks were drawn, they reveal nuances of the artist’s decisions.

And when it’s correspondence with curators and collaborators, they trace the network of relationships in which Gonzalez-Torres worked and lived. One example is two similar Christmas cards sent to Julie Ault and MoMA’s Anne Umland in 1992. Umland’s lightstring snapshot might be the OG Felix Navidad.

The text reads: “Dear Anne, To more years of living, loving, leaving for long train trips, fat cats, sweaters, breathing deeply salty air, new white shirts, unexpected flowers, new friends, streets full of lights, simple moments, views to remember, tough art objects, Paris, moving poems, writing, crying, learning, growing, shopping, hoping, waiting for love letters, heart beatings on one’s [?], little radios, and more, so much more, …in 1993 and beyond, Feliz Navidad, Felix”

One thing I can’t figure out, though: according to the checklist, this is an exhibition copy, on loan from MoMA. Did the museum decide not to loan a piece of correspondence from their archive? Or did Umland keep the personal card, but give the museum a facsimile? What goes into producing a double-sided photo & handwritten text? Because I feel some new facsimile objects coming on.

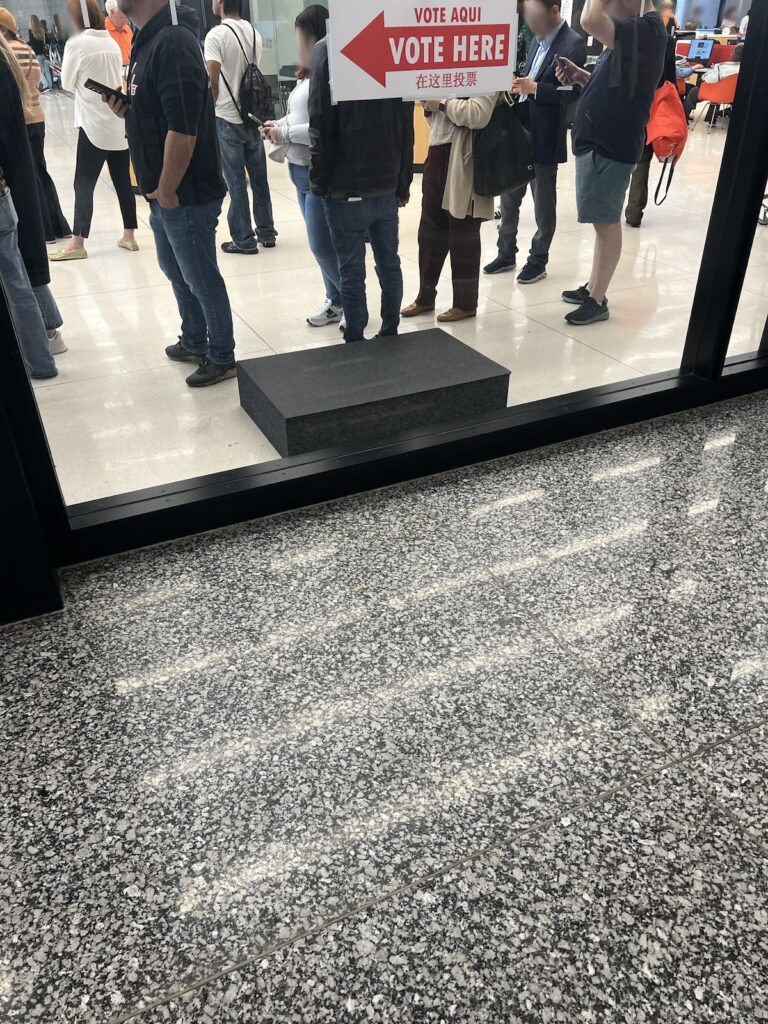

It’s also installed at the National Portrait Gallery, but after seeing the Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation’s instagram, I realized I had missed this 1991 stack, “Untitled” (Party Platform 1980-1992), at the Martin Luther King, Jr. Library. So I went back to see it, and the place was full of people voting.

Oddly, it does not get out much.

Previously: Felix Gonzalez-Torres @ NPG

I’m getting used to not knowing every work David Hammons makes privately, which he may or may not announce until years later. But I am not dealing well with only finding out about public sculptures commissioned more than three decades ago, which turn out to still be chillin’ in the random corner of a park in Atlanta.

TBF, Free Nelson Mandela IS mentioned in the 1988 intro to Dr. Kellie Jones’ 1986 interview with Hammons, one of the rare, foundational texts on the artist and his practice. But it never occurred to me that it wasn’t just a historic occurrence.

Anyway, it is a giant boulder with a “fan-shaped display” of iron bars topped with barbed wire. When it was originally installed, the gate in the prison-like fence was padlocked shut, and the artist had purportedly buried the key under the sculpture. Probably when it was moved to its permanent location in Piedmont Park, Hammons entrusted the key to Atlanta’s politicians, who opened the gate after Mandela’s release from prison.

The sculpture’s wikipedia page doesn’t seem to have been updated since 2012, but by Mandela’s death in 2013, it had been cleared of extraneous, artist-unapproved shrubbery. The interpretation of the Smithsonian’s public sculpture inventory description has the inscription on the work’s back. Would that also have been behind or “inside” the prison fence? I don’t know. The current siting definitely makes the inscription feel like the front, though.

What seems more interesting is how formally resonant this sculpture is to Hammons’ other works of the time. Like, specifically, Rock Fan, the giant boulder topped with antique fans Hammons installed at Williams College in 1993, which is only the biggest of his rock- and fan-related works, if not the only politically topical one.

The full/official/original title of the work is Nelson Mandela Must Be Free to Lead His People and South Africa to Peace and Prosperity. Which, with meddlesome South Africans in the news lately, makes me wonder if Hammons would make a JAIL ELON MUSK sculpture, perhaps in a park in Pennyslvania.

A lot of bangers in the mix at States of Change, a limited-duration, open edition photo print fundraiser to support State Voices, a growing coalition of grass roots organizations around the country that work to preserve and expand voting rights in the US.

A lot of really good artists have put in some very solid work for an important cause at a critical moment. But NGL, these kind of prints are nice, but small—digitally printed on 10×12 paper—and unsigned. So a little slight in themselves. But what they are designed for is to shake $100 or more needed dollars from you. So just pick your favorites and go for it, while you can.

States of Change is open through November 4, 2024, to US citizens and legal permanent residents. [statesofchange.us]

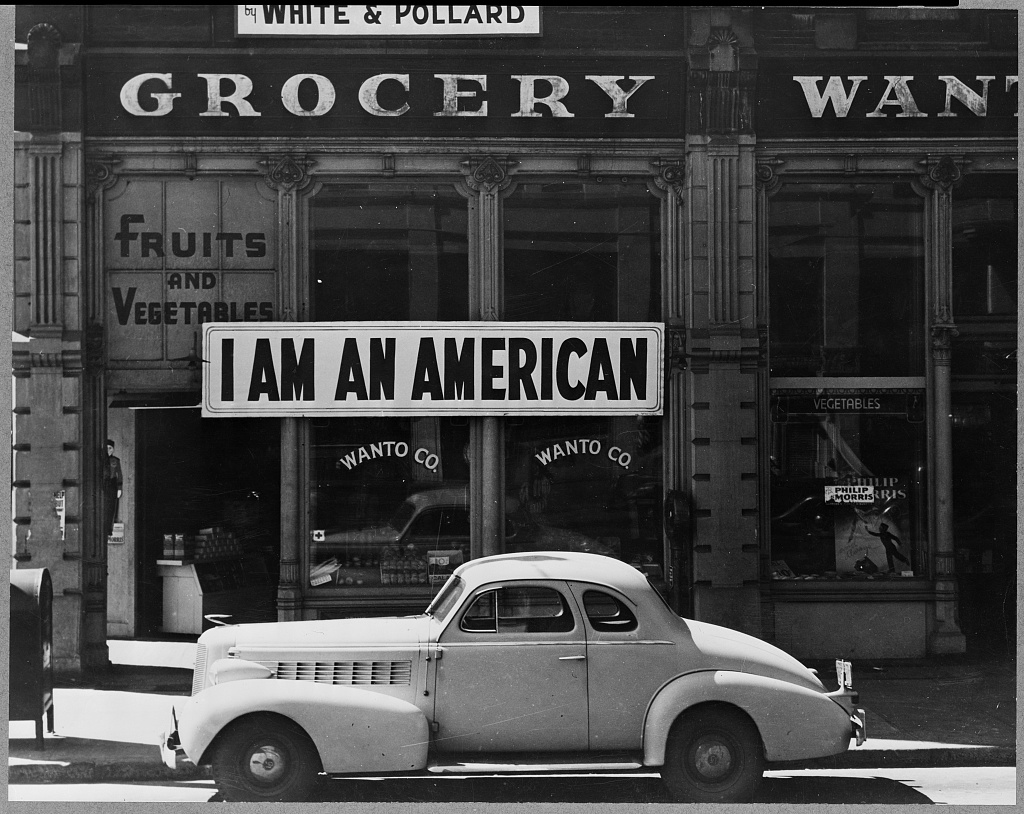

To recognize that censoring Dorothea Lange’s photos of American citizens being incarcerated without charge or cause by the US government because of their race has a long history absolutely does not help when they do it again.

The Wall Street Journal reports that “[U.S Archivist, Colleen] Shogan and her top advisers told employees to remove Dorothea Lange’s photos of Japanese-American incarceration camps from a planned exhibit because the images were too negative and controversial, according to documents and current and former employees. Shogan’s aides also asked staff to eliminate references about the wartime incarceration from some educational materials, other current and former employees said.”

It’s among a whole host of controversial, conservative, and censorious demands Shogan and her team have made as part of the renovation of the National Archives Museum. Every reported change whitewashes American history with explicit conservative slants, and silences or erases non-white Americans.

Just as the racism-fueled shameful injustice of Japanese American incarceration during WWII was ordered by FDR, this cowardly censor running the Archives was appointed by Joe Biden.

[next day reactions update: via @shannonmattern.bsky.social comes Charles Pierce’s context-setting on Shogan’s pre-emptive cowardice in the face of, of all people, Josh Hawley]

Prevously, all too related:

2018: A Brief History of Blogging About America Imprisoning Children, 6/X

2011: I Am An American

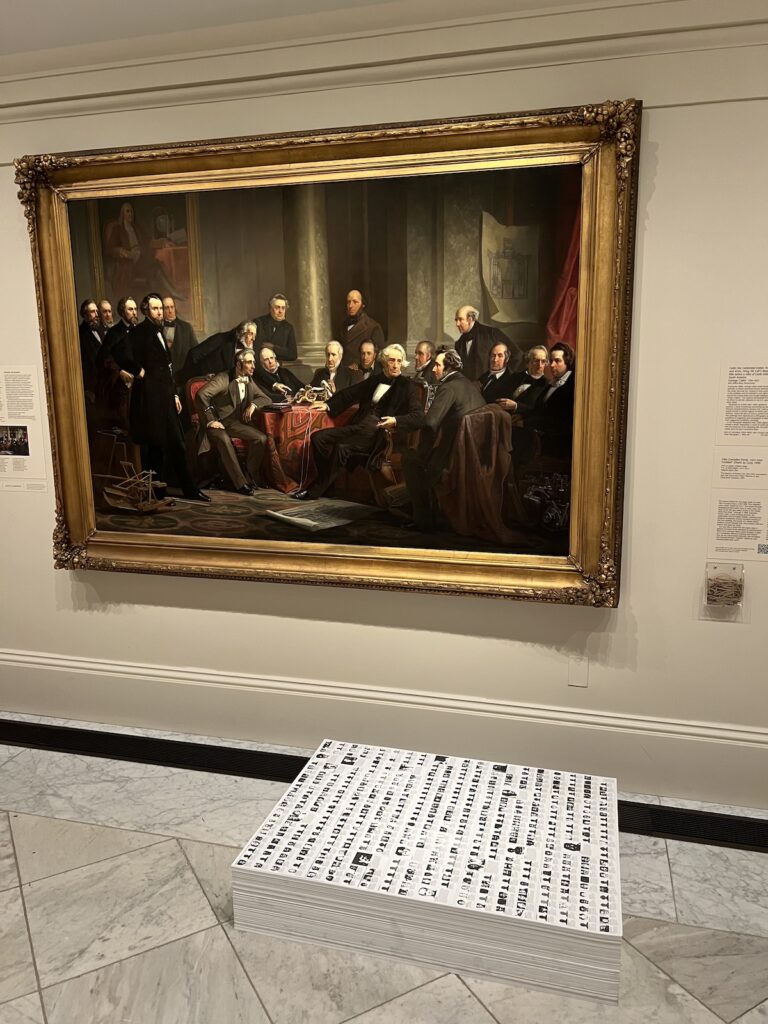

Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Always to Return, at and around the National Portrait Gallery is excellent in several precise and unexpected ways:

The inclusion of all 55 of the artist’s puzzle works [first shown like this at Art Basel 2019, including with five exhibition copies, which I didn’t know was a thing here.]

The inclusion of strong non-signature works like “Untitled” (Fear), above, and “Untitled” (A Portrait), the artist’s only video work.

The inclusion of two variants of the portrait [sic] of flowers on Gertrude Stein and Alice B Toklas’ grave. [n.b.: There are more.]

But the most intriguing and effective thing was the threading of Felix’s work throughout and among the collection of the NPG. It worked in small, even tiny ways, like reuniting a little Eakins portrait of an ancient Walt Whitman with a candy pour, “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), which had been shown together at the NPG’s 2010 Hide/Seek exhibition of queer portraiture.

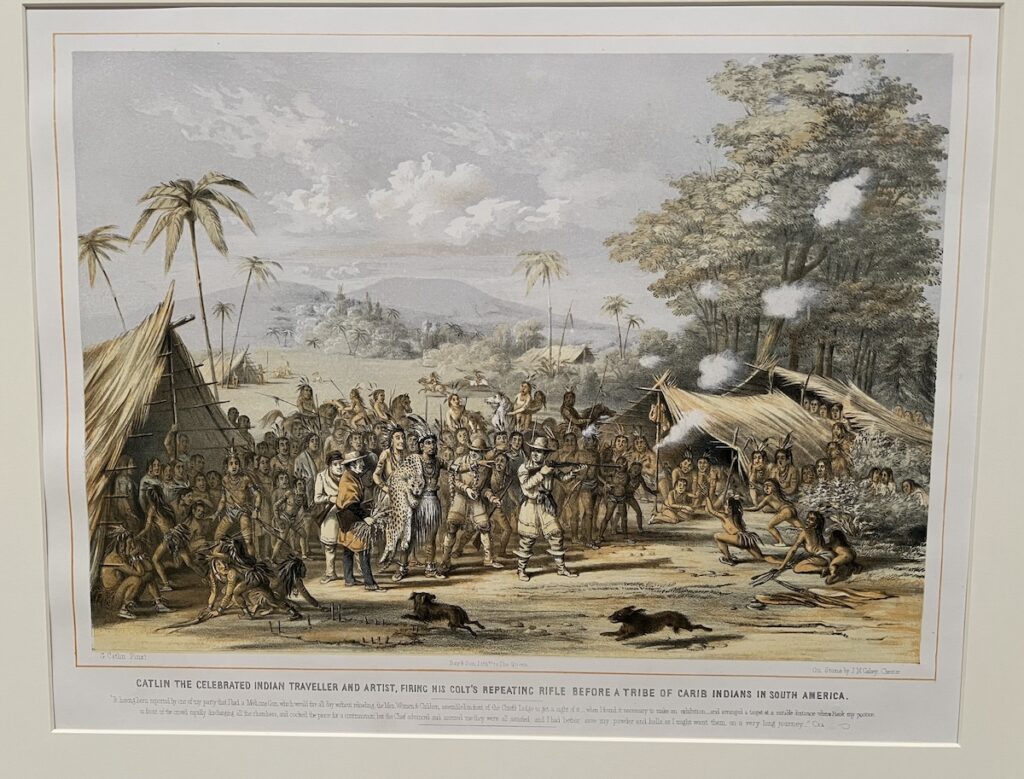

But it hit hardest and most unexpectedly in the most intrusive installation: “Untitled” (Death by Gun), the stack of photos of Americans killed in one week of gun violence, on the floor of a heavily trafficked hall gallery, in front of two works that felt like the NPG’s 19th century bread and butter.

The painting turns out to be Christian Schussele’s 1862 Men of Progress, an amalgamated portrait of various American inventors, including Samuel Colt, inventor of the revolver pistol that made shooting people easier, quicker, and more convenient.

Next to them [in a way I could have photographed all three together, had I only realized the complexity of the connection] is a print after a George Catlin painting, where the artist shows off a Colt rifle to a group of Carib Indians. Turns out that after the economic failure of his massive “Indian Gallery” project, Catlin accepted a commission for a series of paintings for an aggressive marketing campaign promoting Colt’s new guns. That went well. For the gunmakers, at least.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Always to Return runs through June 2025 or until the end of the republic, whichever comes first [npg]

Previously, related: on Hide/Seek and the controversies around its censorship

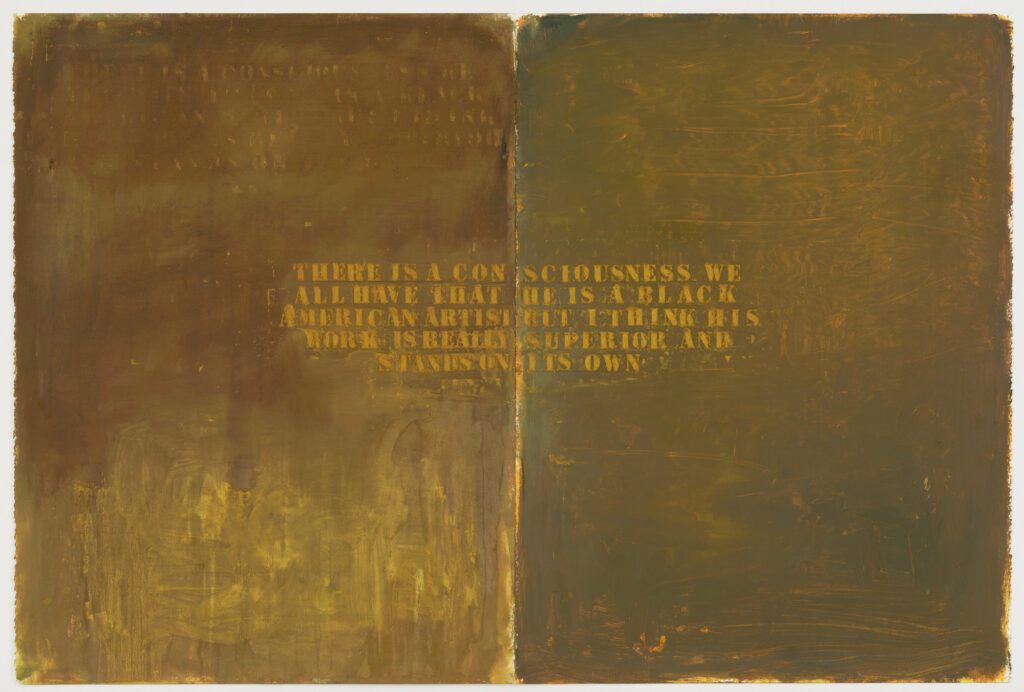

Some time in 1988 before November, Glenn Ligon made Untitled (I Am A Man), which is called his first painting of a selected text, based on a 1968 civil rights protest poster he’d seen as a student in the local office of Congressman Charlie Rangel.

In November 1988, Jamaica Art Center visual arts director Kellie Jones’ proposal of sculptor Martin Puryear to represent the US at the São Paulo Bienal was announced. Puryear was the first Black artist to represent the US at an international exhibition. [He went on to win the grand prize and a MacArthur that year.]

One of the ten members of the Federal Advisory Committee on International Exhibitions, which made the selection, was Hirshhorn Museum chief curator Ned Rifkin, who actually said, to The New York Times, “There is a consciousness we all have that he is a black American artist, but I think his work is really superior and stands on its own.”

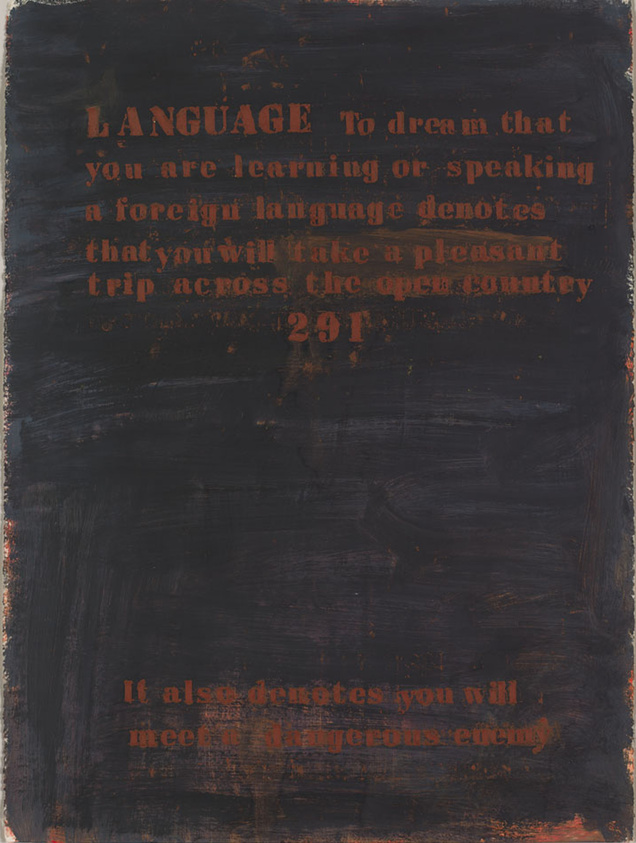

Also in 1988 Ligon was working on stenciling found texts, on paper. Including quotes from “dreambook” pamphlets, street handouts that coupled dream interpretations with advertisement for an underground lottery his father worked at.

And also condescending quotes by major museum curators published in the newspaper. Untitled (There is a consciousness we all have…) comprises two sheets of the same size as the dreambook painting above. It shows an early example of Ligon stenciling a found text multiple times. In a composition similar to No. 291 (Language), faint and effaced versions of Rifkin’s quote can be seen on the top and bottom, respectively, of the left sheet, while the right sheet seems to bear traces of marks made by pushing the stencil itself.

So it is that I only heard of this quote, and this work, this morning, while reading Kriston Capps’ extended reflection on the Hirshhorn in the Washington Post occasioned by the museum’s 50th anniversary. Capps’ reference sent me on a search for the work and the quote, and the curator and the context.

And I thought this is how it must have felt to first encounter Ligon’s work. Much is made of Ligon’s choices of text and the resonance of their sources, but it feels worth noting how much of that information exists apart from his paintings. Though he eventually began mentioning titles in his own titles, early sources like dreambooks and Ned Rifkin were untraceable and unrecognizable, at least to someone who didn’t live them. So their first reference is Ligon, who put them there, not the source he got them from. Which makes Rifkin’s quote even more outraging, offensive—and, for a young Black artist reading it, dispiriting.

In 1991 Ned Rifkin left the Hirshhorn for the High Museum in Atlanta, and Ligon was in his first Whitney Biennial. In early 1993, presumably before he showed Notes on the Margin of The Black Book at the Whitney Biennial, the Hirshhorn acquired their only Ligon works to date: a door painting, Untitled (Black Like Me #2), and Untitled (Four Etchings), both from 1992. The painting was loaned to the White House for four years beginning in 2009. The National Gallery of Art acquired Untitled (I Am A Man) in 2012.

In 2018 Andrea Fraser published 2016 in Museums, Money, and Politics, a 933-page report documenting the 2016 political expenditures of all the trustees of 125 museums across the United States. More than half the $6.4 billion poured into the 2016 US elections came from just a few hundred people, and, Fraser finds, most of them also dominate the country’s art and cultural institutions.

It is described as “like a telephone book,” by which I hope they don’t mean “so obsolete half the people alive right now have never seen one.” Well, now’s your chance. Fraser’s 2016 has been released as a PDF, available at the Wattis Institute. It includes texts by Fraser and Jamie Stevens, who led a year-long season of events and exhibitions at the Wattis focused on Fraser’s work.

It is still available in print, too, and I hope a suitable number of copies will be secreted away around the globe to show future historians of the 21st century that at least some people were aware enough to put out exhaustive reports.

Andrea Fraser, 2016 in Museums, Money, and Politics, published by Westreich Wagner, CCA Wattis, and MIT Press, in PDF and print ($125) [wattis.org]

Previously, related: Why Does Andrea Fraser’s Work Make Me Cry?

For folks looking for less disturbing McDonald’s-related pictures at the moment, somehow Joel Meyerowitz, of all photographers, is here to oblige. [via @mlobelart.bsky.social]