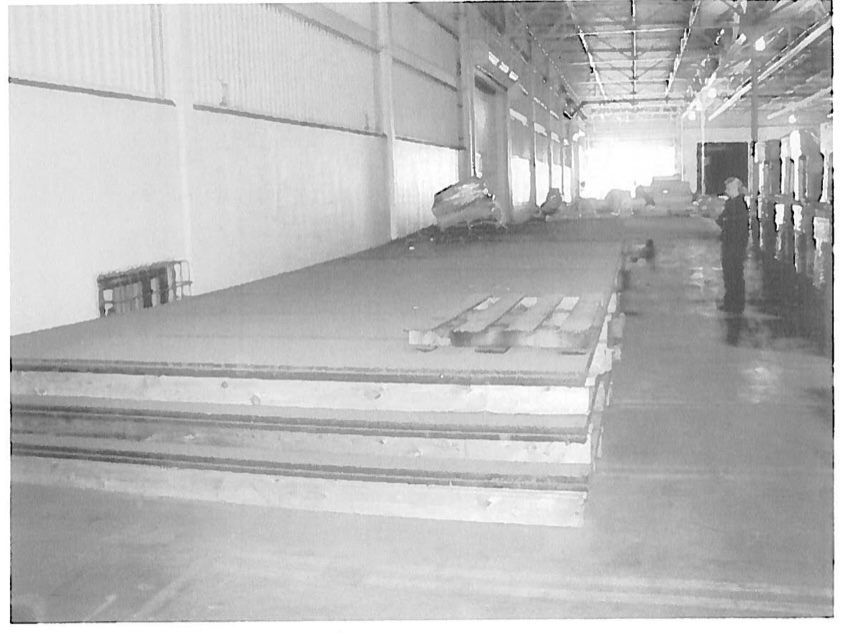

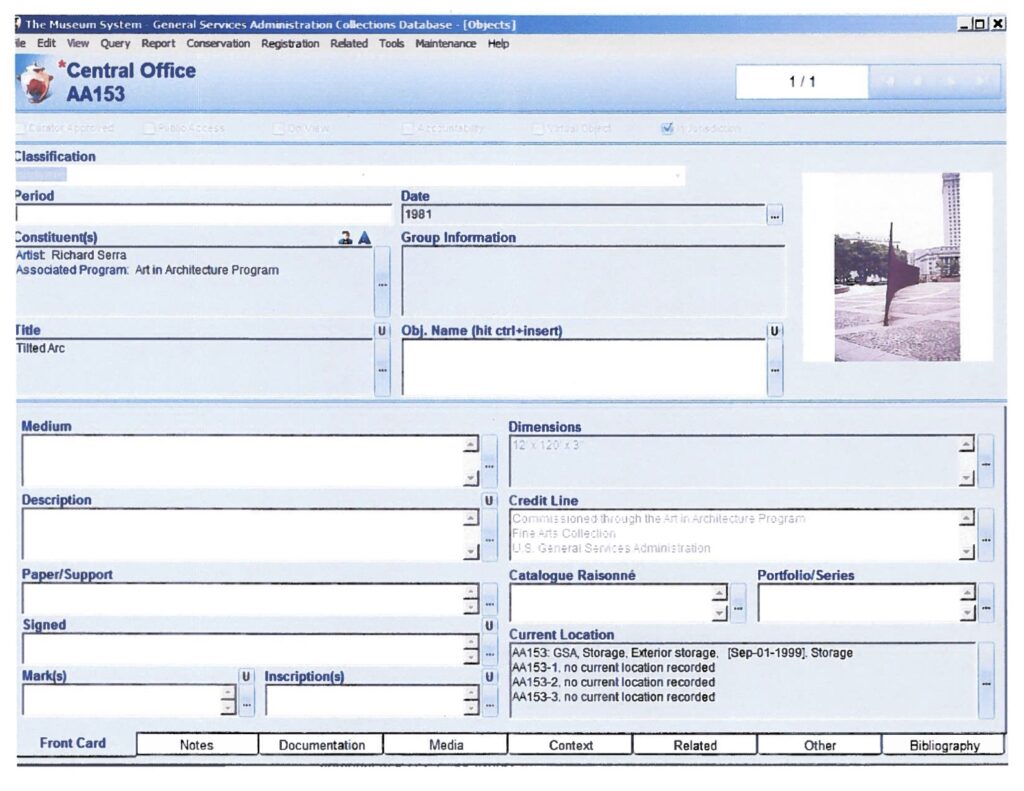

The General Services Administration commissioned Tilted Arc from Richard Serra in 1981 as part of a Percent for Art program. The GSA’s regional manager guided the campaign to have it removed in 1985. It was finally removed at night on March 15, 1989 after Serra’s contract- and free speech-related lawsuit was dismissed. The three Cor-Ten steel plates that comprised the sculpture were taken from the Javits Building plaza in lower Manhattan to a government-owned parking lot at 3rd Avenue & 29th St in Brooklyn. The site was adjacent to the Metropolitan Detention Center. In 1999 the Bureau of Prisons built a new joint on the site, and the pieces of Tilted Arc were sent to a GSA depot at Middle River, Maryland. And there they stayed, on a loading dock, stacked and separated by pressure-treated lumber, as the GSA put it, “indefinitely.”

Which is not the same as forever. The government sold the Middle River site, and Tilted Arc was moved to the GSA’s Fine Art Storage facility in Virginia in the summer of 2005. [18 pallets of relief sculpture molds by Ray Kaskey for the World War II Memorial were also moved, but in different trucks.] It remains there to this day. I saw it yesterday, in fact. [Tilted Arc, that is, not the molds.]

By at least 1993, the GSA conducted regular evaluations of the condition of the Tilted Arc plates. [From the 2001 email thread submitting the first report from Middle River: “The iron curtain is still here.” “Norman reports the sculpture is still on the loading dock and is fine.”] In 2004 it was noticed that they were rusting unevenly due, it was determined, to moisture being trapped in the lumber and held against the otherwise protective oxidized surface.

After an evaluation by McKay Lodge, an art conservation firm which has long held contracts to maintain GSA artworks around the country, GSA issued a statement of work [pdf] to “STABILIZE TILTED ARC.” I find the text below, giving background to the proposal, to be extremely helpful in seeing how the GSA views the artwork:

In 1968 GSA constructs the U.S. Customs Court and Federal Building at 26 Federal Plaza, along lower Broadway in New York City. Due to prohibitive inflation and shifting policies within the agency, no public artwork is funded at the time of construction. In 1979, GSA authorizes the Art in Architecture Program to allocate funds for Richard Serra to create a public artwork for the Federal Plaza, on the corner site adjacent to the U.S. Customs Court and Federal Building (now named for Senator Jacob K. Javits). Serra’s sculpture, known as Tilted Arc, is installed on July 16, 1981.

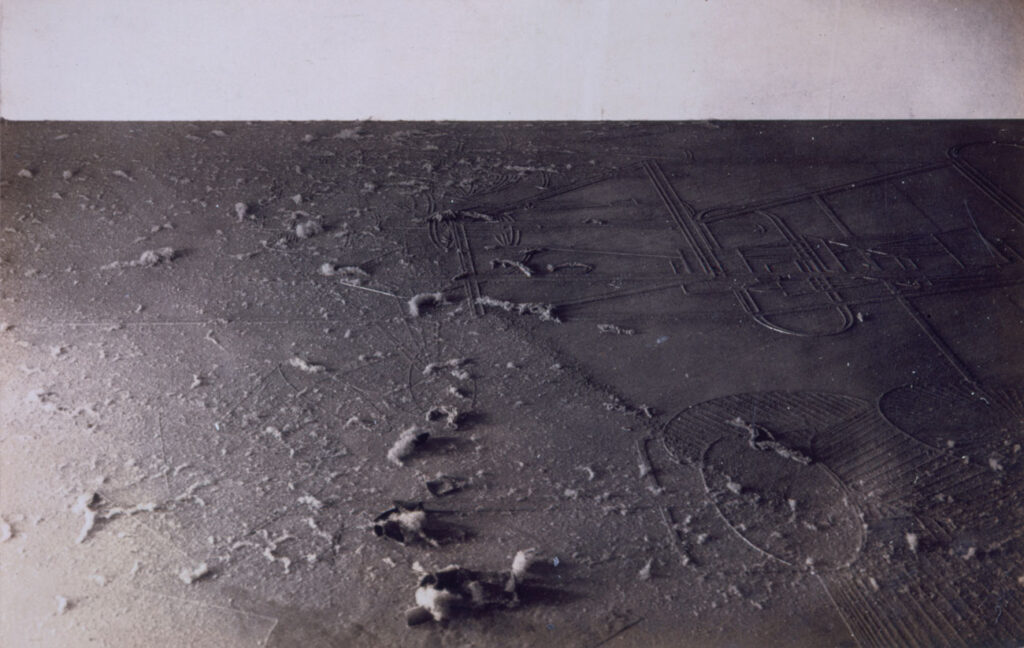

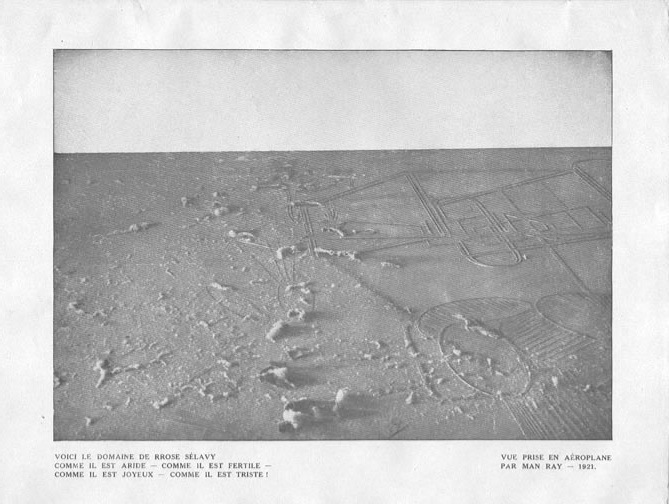

The sculpture was looming and domineering, and an interesting study in the manipulation and compression of public space. Cast in steel, the arc stood 12′ high and 120′ long, and when it [was] on the plaza, it obscured all views of the city beyond the brown metallic wall. [sic obv]

GSA Dismantles Tilted Arc

In June of 1986, the National Endowment for the Arts announces that it will assist GSA to locate a new site for Tilted Arc. However, Serra adamantly reiterates that the sculpture is site-specific, and if moved will be rendered meaningless. [again, sic obv]

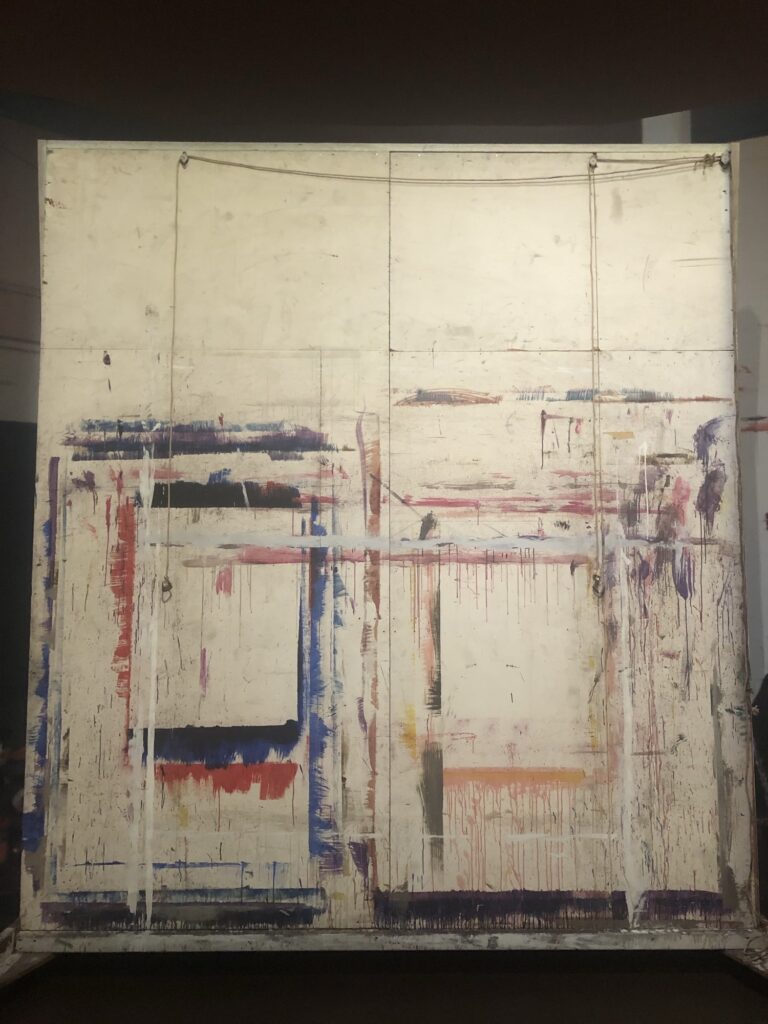

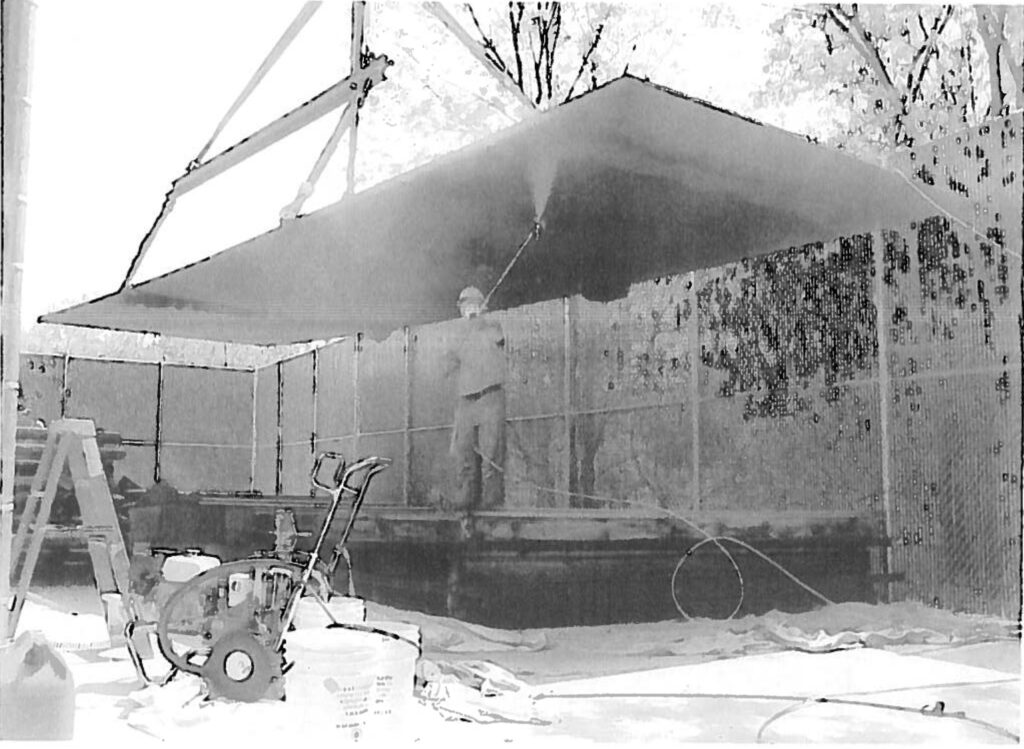

McKay Lodge proposed to treat the plates with a marine anti-corrosion film. They were unstacked, cleaned and sprayed, and restacked. The conservator’s report noted that “the predicted problem [uneven corrosion] had occurred to some extent, but pitting had not yet occurred to a degree that the steel would be permanently marred. Nevertheless, it revealed the importance of coating this steel if it is to be stored for years, and the work was performed just in time.”

McKay Lodge recommended reapplying the film as needed every 3-5 years, and to minimize exposure to rainwater by “fastening a covering of plywood over the length of the newly [re-]stacked steel plates and then tying over this waterproof tarps sufficiently fastened to avoid wind lifting.”

No one seemed to suggest researching how other Richard Serra sculptures fare while exposed to the elements, or how other Serra sculptures are stored. In 2009, while the GSA was in the process of spraying their steel plates, Serra himself stored sculptures outdoors, on the riverfront, in the Bronx, by keeping them upright. Just today Michelle Young wrote about visiting the Serra sculpture owned by the city of Paris, which is stored outdoors and upright at a municipal depot.

Clara Weyergraf-Serra and Martha Buskirk’s foundational 1990 book, The Destruction of Tilted Arc: Documents WAS Tilted Arc for me, so I FOIA’d Tilted Arc in 2015 because I’d wanted to see where it was, and what happened to it after it was removed. I also wondered if any consideration or analysis had been done relating to Tilted Arc in 2010, when the Jacob Javits Building plaza was being redesigned for the second time. [In 1997 Martha Schwartz’s sinuous bench maze replaced the planters and benches that had been scattered across the original architects’ plinth-with-fountain plaza.] The proposal documents from Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates, who was selected for the redesign, did not show any trace of historical review or evaluation of reinstalling Tilted Arc. The focus, if I recall, was on alleviating drainage and ventilation problems in the parking lot under the plaza.

When I went to see Tilted Arc‘s situation in 2015, it was indeed encased in an armature of some kind and wrapped in blue tarp. The warehouse complex felt obscure, but neither secret nor restricted. In the intervening years, development around the site has accelerated. There is a new Wegman’s nearby, and countless condo and office towers. The warehouse next to Tilted Arc‘s storage area is now a microbrewery, with outdoor seating. While I’ve been not disclosing its location all this time, I’ve heard from multiple people of their visits.

When I went yesterday, the tarp was off, the plywood was rotting and covered with fallen leaves. The protective coating that is supposed to cure to a white film when active was not visible to me. While ignoring the decades of Serra conservation experience now accumulated by museums and collectors around the world, GSA appears to not even be following their own basic policies to keep the work intact. Preserving Tilted Arc by clamming up and ignoring it is not working.

Preserve it for what, you ask? Didn’t Serra himself declare it destroyed? The actual answer to that is, yes, no, and we don’t know. In his introduction to The Destruction of Tilted Arc: Documents, Serra quoted his own statement to a 1984 GSA hearing: “I want to make it perfectly clear that Tilted Arc was commissioned and designed for one particular site: Federal Plaza. It is a site-specific work and as such not to be relocated To remove the work is to destroy the work.” To which he added, “This has been accomplished; Tilted Arc is destroyed.”

So if the US Government put it back in Federal Plaza tomorrow, would it no longer be destroyed? What parameters of that site must be specified for Serra to have considered it a viable work again? Did he say? Did anyone think to ask? [Anyone besides me, I mean. In 2015 I suggested to a mutual friend that he ask Richard to at least document his intentions for Tilted Arc, in hope that it might ever be reinstalled some day. I don’t know if he did, but the time when we can’t ask anymore has come.]

Tilted Arc was removed because an art-hating judge, a Reagan appointee, and Rudy Giuliani wanted to score political points by destroying something that mattered to people they hated. The people angry at the government for chopping it up and destroying it were wrong; that government dismantled it the same way they installed it—look at those tongue & groove joints, it just slides apart!—and they’ve spent 35 years storing, moving, protecting and conserving the pieces of it.

To what end? Serra shut down the possibility of selling it off; no collector or institution would take a destroyed Serra […unless?] So why take this effort if not to preserve the possibility of reinstalling it? How does that play out? Serra himself was obviously never going to ask for it, but he’s gone now. The GSA seems uninterested to pursue it on their own. So who makes it happen? Are Serra collectors in a Whatsapp group chat right now trying to figure it out? Could you imagine a more fitting monument to oligarchs colluding to get the government to do whatever they want than a resurrected Tilted Arc?

Or maybe it’s just a government that does its job, takes care of things, appreciates the arts, recognizes a sculpture’s significance, and creates the opportunity to do something better. The history of Tilted Arc is long, but it bends back toward Manhattan.