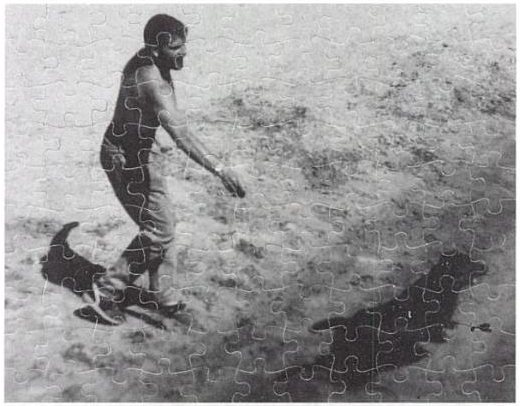

These are mostly for me, just kind of gathered here without order or comment for the moment. I’ve been thinking about Alberto Giacometti lately, and his sculptural, spatial pursuit of that moment when a figure comes into view.

Arthur C Danto in The Nation 2001 about Sartre in 1948 on Giacometti:

Sartre says something even more striking about Giacometti’s figures. “The moment I see them, they appear in my field of vision the way an idea appears in my mind.” This is a way of explaining the somewhat ghostly feeling of his figures, as if they were persons whose bodies had been all but erased. Giacometti was legendary for destroying his work–his studio floor would be found littered with broken plaster in the morning, after undoing a night’s work. I think this was the result of an impossible effort to eliminate whatever gave them the solidity that belonged to their material condition as sculpture.

Rosalind Krauss in Artforum 2001 quoting Sartre in 1948 on Giacometti:

“Giacometti,” Sartre wrote, “has restored an imaginary and indivisible space to statues. He was the first to take it into his head to sculpt man as he appears, that is to say, from a distance.” And because this is man as he is perceived, it is fitting that these sculptures should all be vertical, since Sartre equates perception with walking, traversing space, doing things, just as he links imagining with the body’s repose. If one dreams lying down–as in the sculptor’s earlier, Surrealist, s leeping women–one perceives standing up.

Michael Kimmelman in NYT 2001 on Giacometti’s MoMA retrospective:

In the 1940’s and 50’s, when he made extremely thin heads, flattened on both sides like pancakes, Giacometti talked about the effect of looking at somebody straight on, then from the side. He was rejecting the Cubist idea that it was possible to keep different views of the same person in sight at the same time. ”If I look at you from the front, I forget the profile,” he said. ”If I look at you in profile, I forget the front view.” Which is precisely what happens: if we move 30 degrees left or right off-center of these heads, the face becomes a profile. Back six inches, the profile disappears. If we move: the work is about our distance from the figures, our position vis-a-vis the heads or striding men or standing women.

Kimmelman in the NYT 1996 reviewing David Sylvester’s incredible book, Looking at Giacometti:

The issue for Giacometti became the pursuit of what he called likeness. Roughly, it had to do with trying to represent the real experience of seeing, apart from artistic conventions: on the simplest level, conveying the actual swimmy sense of distance and engulfing space when viewing figures across, say, a broad street, or conversely, the vertiginous foreshortening you get when standing face to face with someone. Likeness also had to do with something less tangible but still real: the intense sensation of the shared gaze between living artist and living model. Mr. Sylvester contrasts Giacometti with Matisse in this respect. “The Matisse sculptures present a figure seen whole and entire now, in an instant of time, in any instant of time, meaning outside time,” he writes. “The Giacometti sculptures seem to present figures as they are perceived while time passes.”

I’ve GOT to get Sylvester’s book out of storage this weekend. That, and Herbert Matter’s photobook of Giacometti’s sculptures. I have my Bonnefoy, of course, which is beautiful to look at, but nearly impossible to read. Just, wow, what is going on there?

image: City Square, 1948, via moma.org