In addition to the world’s greatest artist website, artist Gerhard Richter also makes paintings.

Now these two endeavors come together with the debut of a micro-site devoted to 4900 Colours, the set of 196 5×5 grids of 25 randomly applied enamel-painted squares, mounted on Aludibond panels. 4900 Colours can be exhibited in any of 11 configurations. Above is Version IX, which I chose for its apparent zooming-in-on-pixels quality.

One point of note: the website lists 4900 Colours in the /editions/ folder. Update: the microsite URL has changed; it is now listed in /paintings/

And two points of great relief: the 4900 individual squares were indeed sprayed-on enamel, not handpainted by the finely dressed artist; and there are no drop shadows. I think we are making real progress here.

www.gerhard-richter.com/art/paintings/4900-colours/ [gerhard-richter.com via @gerhardrichter]

Previous coverage of 4900 Colours:

The Making Of, with special guest star Benjamin Buchloh

About facture and that handpainted square

About drop shadows and diagrammatic abstraction

Category: inspiration

The Wildman Of Chelsea

So woohoo, Andrew Russeth pointed back to a Charlie Finch artnet gossip column from 1998, and just wow. I was there, I mean, I remember a lot of that stuff, and it is freaking me out how alien and long ago and far away it all sounds.

One thing I didn’t know or remember, was Finch’s story from John Weber, about how he found a 1961 Robert Smithson painting in his storage while preparing his move to West 20th Street. It was called The Wildman of Chelsea.

Finch’s is the only mention I could find of it online.

But it got me thinking [again]. Smithson’s Floating Island was posthumously realized based on a simple 1970 sketch, right?

And Smithson left plenty of other comparably detailed sketches for projects. Who’s to say that The Wildman of Chelsea isn’t an early work in the series?

What’s to stop someone from realizing Wildman right now, right here? With all the beards and jorts pegged jeans around town these days, it could probably be done and posted to flickr before dinnertime.

Obviously, what’s really needed is a band of historically accurate enthusiasts to start researching this stuff in depth, and then re-presenting it, for both the aesthetic benefit of the public, but also for one’s own experiential edification. It’s like Marina Abramovic’s white-coated MoMA crew meets Civil War re-enactors. For Smithson.

The Robert Smithson Re-enactors Society.

The Hamamatsu Photonics R1449 And R3600 Photomultiplier Tubes

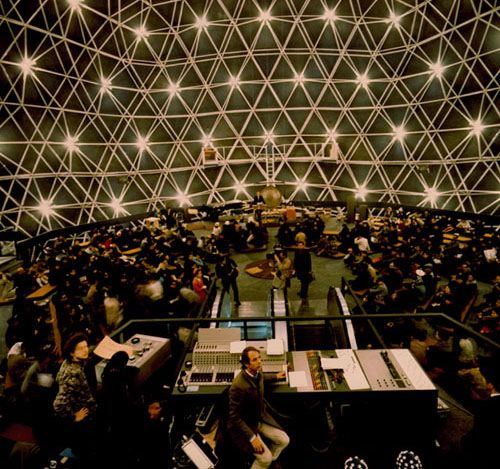

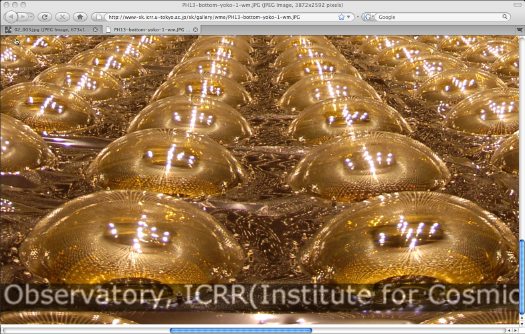

Photomultiplier Tubes, or PMT, are vacuum tubes used to detect electromagnetic energy. In 1979, Hamamatsu Photonics began development of the world’s largest PMT, 25 inches across, which would be used in the Kamiokande proton decay detector being constructed by the University of Tokyo in a mine in rural Japan.

Photomultiplier Tubes, or PMT, are vacuum tubes used to detect electromagnetic energy. In 1979, Hamamatsu Photonics began development of the world’s largest PMT, 25 inches across, which would be used in the Kamiokande proton decay detector being constructed by the University of Tokyo in a mine in rural Japan.

Within a year, Hamamatsu had managed to design a 20-inch (50cm) PMT, and successfully manufactured it by 1981. It was dubbed the model R1449:

Because this was a 20-inch PMT, the biggest question was whether or not its cathode could be manufactured correctly. The days leading up to the completion of the first PMT were anxious. Moreover, in steps such as antimony evaporation, there was no other recourse but to rely on the eyes and judgment of those professionals performing the tube evacuation task. An ordinary PMT can be held in the worker’s hand throughout the production process, but the large 20-inch PMT first had to be secured in place. Then, the worker could perform his required tasks while walking around the outside of the PMT. The workers donned protective helmets equipped with explosion masks, mounted steps to the platform holding a large pumping bench, and began the final fabrication, which consisted of making the photocathode and sealing the PMT.

The color formed from oxygen discharge in the photocathode manufacturing process was visually attractive. When made to react with potassium after antimony evaporation, the tint immediately changed to an ideal color for a photocathode. Cheers arose from the staff gathered around the pumping bench, as it was a moment of high emotion for everyone.

Hamamatsu delivered 1,050 R1449 PMTs to Kamiokande, where they lined a giant tank of ultra-purified water 1,000 meters below the surface.

In 1987, the PMT array at Kamiokande detected for the first time neutrinos given off by a supernova. [It was a discovery for which Professor Masatoshi Koshiba [above], who spearheaded the Kamiokande research, was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2002. Those may be the two most awkwardly constructed sentences in this post.]

Meanwhile, an even larger detector was being planned for Kamiokande. Dubbed Super-K, the new tank, 39m high and 41m in diameter, would hold 50,000 tons of water and 11,200 PMTs. These new, improved PMTs, known as model R3600, were based on the R1449. They cover approximately 40% of the interior surface of the tank. Super-K began operations in 1996.

On November 12, 2001, as the tank was being refilled, a PMT imploded, sending a shock wave through the water, and causing a chain reaction which destroyed around 6,600 other PMTs.

The survivors were redistributed, protective acrylic shells were added, and research resumed. Beginning in 2005, newly manufactured R3600s were installed. The detector reopened in 2006 as Super-K-III.

According to reports at the time of the implosion, an R3600 cost around $3,000 new, an extremely reasonable price for such a magnificently crafted object. I would most definitely like one. Also a convenient display stand. Also, that tank is absolutely stunning. If I were a sculptor of shiny round objects of a hundred feet or more in diameter, I would find it hard to get out of bed in the morning knowing this exists.

20-Inch Photomultiplier Development Story [hamamatsu.com, the original Japanese version is a little more dramatic]

portrait of Prof. Koshiba hugging a Hamamatsu R3600 [u-tokyo.ac.jp]

hi-res images in the Super-Kamiokande photo album [ICCR at U-Tokyo]

Accident grounds neutrino lab [physicsworld]

The Rainbow Bombs

NPR’s Robert Krulwich had a fascinating story the other day that works even better online. Because there are slideshows and video footage of Starfish Prime, the hydrogen bomb the US detonated in space on July 9, 1962.

The launch occurred on Johnston Island in the South Pacific, and was part of an early test of ICBM technology–and an attempt to understand the weaponizing potential of the earth’s Van Allen radiation belts. Just in case Moscow was up to anything funny.

Scott Hansen pointed to Peter Kuran’s excellent-sounding documentaries about atomic testing, including Nukes in Space: The Rainbow Bombs.

Almost a thousand miles away, Hawaii had been primed for a potentially “dazzling” light show. NPR’s lead-in called it “the single greatest manmade light show America has ever created.”

And Starfish Prime delivered. Cecil Coale, who was involved with the launch and monitoring it from Johnston Island, described the flash that turned night to day and the ionizing rainbow that followed:

“It was like a flashbulb…then the sky turned green for a second.

then yellow and blue, “really vivid, unnatural bright color.”

Then red. “it wasn’t shimmering it was glowing red like a neon sign. Then it slowly disappeared, there wasn’t any sound to this at all, it was entirely visual…i think about this every day of my life.”

Listen to the Bomb Watchers [npr]

DOE library of historical nuclear test films of Operation Dominic, Operation Fishbowl, and Starfish Prime [doe.gov]

Blow

This FT essay by Daphne Guinness about buying Isabella Blow’s estate before it was dispersed at Christie’s is a wonderful, sad, incredible thing. [via @artnetdotcom]

All the way back in 2002, I overwrote a long post about Blow, Walter Benjamin, Bill Cunningham, fashion, and street photography. The occasion was Guy Trebay’s writing about street fashion.

Frankly, I’m surprised at how much of it I’d forgotten. Did Benjamin really call the flaneur “a spy for the capitalists, on assignment in the realm of consumers”?? That is awesome, I could totally use that!

What I’ve never forgotten, though, is Cunningham’s expertly serendipitous street photo of Isabella Blow blowing into a fashion show in Paris:

Wilkommen To The German Dome

Daphne, As Photocopied By Sigmar Polke

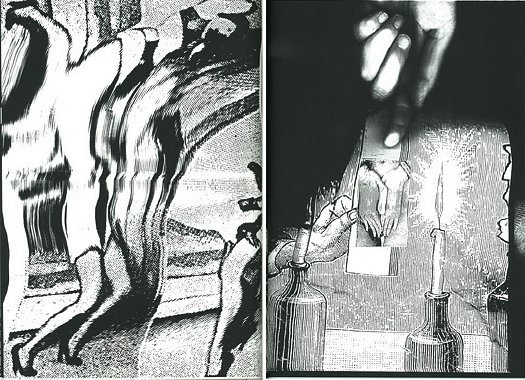

I didn’t follow Sigmar Polke’s work closely. At least not consciously.

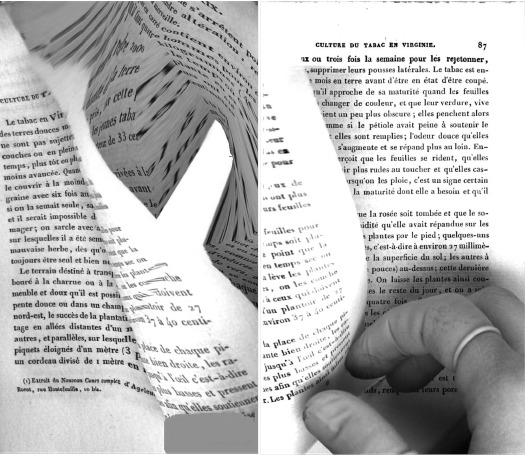

This excerpt from Reiner Speck’s essay about Polke’s 2004 artist’s book Daphne is awesome, even if it sounds a bit like someone’s been huffing toner at the end:

An oversize anthology of sources of visual inspiration, a photocopied book that paradoxically reveals the artist’s hand, a sketchbook for the machine age–Daphne runs and runs, is caught by the photocopier, and runs some more, only to be bound in the end.

Created directly by Polke himself, Daphne is a book with 23 chapters illustrated in large-format photocopies. Each “copy” of the book differs, as each has been photocopied and manipulated individually, pulled from the machine by the hand and watchful eye of the artist.

Process is revealed, over and over again. Motifs accumulate page after page, as do small graphic cycles. The printed dot, the resolution, the subject, and the speed all determine and are determined by the apparently unpredictable and often impenetrable secret of a picture whose drafts are akin to the waste products of a copying machine.

Even if the motifs in this book provide but a brief insight into the artist’s hitherto secret files and archives, it is still a significant one.

For the first time, we witness an artist’s book with such an aura of authenticity that Walter Benjamin’s seminal essay, “Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” bears consequent re-reading.

Produced in a limited edition of 1,000 “copies,” each of which has been numbered and signed by Sigmar Polke.

A thousand copies of a 440 page book [40 pg essay, 400 images], each one manipulated by the artist? How long does that take?

Let’s assume, for logic’s sake, that he made 1000 copies at a time for each A3 page [16.25×11.5 in.], manipulating it around the surface of the copier as the copies fly. The Konica Minolta Bizhub Pro 1050 commercial copy/printing system had a maximum speed of 105 pages per minute. But that’s only for letter-size, and it wasn’t introduced to the market until October 2004. [Newer Bizhub Pro models are up to 160 ppm.]

Which means that the 2003-4 state of the copying art was probably around 50-60 larger pages per minute. Say 50, and we have a nice round 20 minutes of copying time per page, 133 hours of copying. That’s 16.67 8-hour days of nothing but copying. Add in lunch, breaks, maintenance, and you’re looking at three weeks, easy, standing there at the copy machine. Let me repeat the word “copying” again, just for emphasis. Copying.

Now imagine coming up with a suitable repertoire of moves for a page on a glass plate. I mean, how varied can you really get? Do these process-centered motifs and tricks emerge from the book, too? If they could be projected sequentially, like the frames of a movie, the 1000 copies of a single page would compress all of Polke’s moves into a 42-second clip. If the movies for two pages were screened side by side, would they reveal randomness, an identifiable bag of tricks, or perhaps Polke’s carefully choreographed handjams?

Surprisingly, the least expensive copy of Sigmar Polke’s Daphne is on Amazon. $675 [amazon]

More images from Sigmar Polke’s Daphne at Stopping Off Place [stoppingoffplace]

[Inadvertently] Related: Nouveau manuel complet du fabricant et de l’amateur de photos

update: oh no/yeah, it’s a “new york trend”! [thanks, andy]

The Greatest Camo Story Ever Told

Sure, there’s Dutch Camo Landscapes, and Razzle Dazzle, and the Civilian Camouflage Council, but it all pales in comparison to the truly epic WWII camo accomplishments of Jasper Maskelyne and The Magic Gang.

Sure, there’s Dutch Camo Landscapes, and Razzle Dazzle, and the Civilian Camouflage Council, but it all pales in comparison to the truly epic WWII camo accomplishments of Jasper Maskelyne and The Magic Gang.

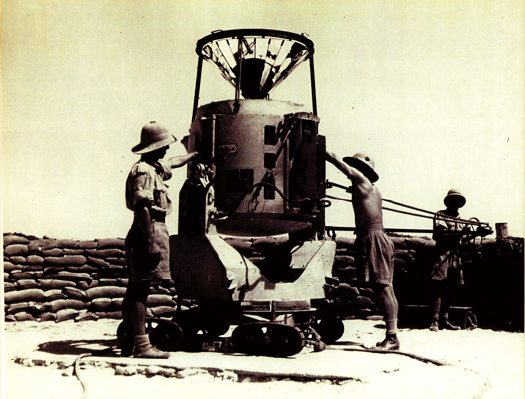

Maskelyne was a British magician-turned-Army camo mastermind who, in 1941, led a ragtag band of desert artists and illusionists who created a series of incredible camo techniques that protected Allied forces in North Africa from aerial reconnaissance and bombardment.

Using burlap and sticks, they disguised trucks as tanks, and tanks as trucks, and they created devices to enable tanks to cover their own tracks across the desert sands. But the most amazing achievements are in his 1949 memoirs, Magic – Top Secret where Maskelyne–whose grandfather, also a magician, invented the pay toilet–tells how he saved the port of Alexandria, Egypt from night bombing by building an elaborately lit decoy port, several miles away in the desert. Using incendiary devices and real anti-aircraft artillery, he and his Magic Gang fooled the German bombers with realistic-looking “hits” and return fire; and by morning, his crews would strew papier-mache rubble around the real port, giving simulated damage for the reconn pilots to report back. [below: a German spy photo of part of the port]

The success of the Alexandria decoy was only surpassed by Maskelyne’s brilliant [literally] strategy for protecting a vital supply route for the Allies, the Suez Canal. He designed “Dazzle Lights,” a rotating structure of made up of mirrors and 24 powerful anti-aircraft searchlights that, when set into motion, gave off a “Whirling Spray,”:

[Maskelyne] managed to create beams nine miles long, twenty-four of them from each searchlights [sic] … the magic mirrors were a success, and the next job was to get the device into mass production. With them, we made twenty-one searchlights serve for the entire one-hundred-mile length of the Suez Canal.

That’s right, the Suez Canal was saved from being bombed by the biggest lightshow in history: the 100-mile-long, Whirling Spray of almost two dozen Dazzle Lights.

How is it possible that I did not know this before now? Why is this miracle of modern warfare not taught in our military academies? Our elementary schools, even? How are these mindblowing aesthetic achievements not celebrated as a landmark in the history of art? Why is there no Bruckheimer movie, starring Josh Hartnett as the daring soldier magician? Maybe because the entire thing is bullshit.

In 2004, military historian and magician [seriously] Richard Stokes published the findings of his multi-year investigation into Maskelyne’s claims. They are gathered in the exhaustively paged website, MaskelyneMagic.com. Working with the magician’s son, he had access to Maskelyne’s archives and scrapbooks from the war. Stokes also cross-referenced official records, declassified intelligence reports, and consulted experts and historians in the North African war. And there is nothing in the historical record to support Maskelyne’s fantastical claims.

On Alexandria, the place where he said he built a decoy port doesn’t even exist; neither does the geography he describe match to any in the vicinity of the city. There are no pictures or corroborating eyewitness accounts, and no documentation.

On the Suez front, Stokes demolishes Maskelyne’s claim to have invented Dazzle Lights by pointing to similar, tank-based tactics under development since WWI. Again, no record of Dazzle Lights can be found in the historical source material, and extensive accounts of the actual defense of the Canal provide well-documented alternative explanations to Maskelyne’s. According to Stokes, Maskelyne didn’t actually come up with the Whirling Spray idea until 1942, after the aerial threat had subsided. And he quotes the illusionist’s son: “The ‘Dazzle Lights’ were an idea which was, I believe, constructed only in one prototype and tested on one occasion.”

Which appears to be the scene depicted in the photo gallery on Stokes’ site, where a searchlight is being outfitted with a faceted, mirrored cone extension:

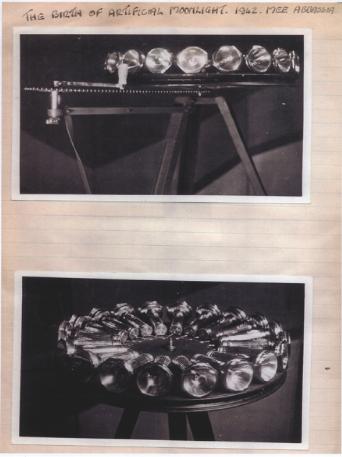

Which means the photo below, showing an awesomely Duchampian folly, 18 flashlights on a turntable, is somewhat confusing to me:

But with a caption like, “The birth of artificial moonlight, 1942,” I’d think that Maskelyne’s imagined heroics are long overdue for [re-]creation.

The War Magician| “”Myth is invulnerable to mere facts” – Barthes [all images via MaskelyneMagic.com]

Previously: Bombardment Periphery, Rotterdam, and Los Angeles’s ‘wigwam’ of searchlights; Forrest Myers’ light pyramid

Nouveau manuel complet du fabricant et de l’amateur de photos

So fantastic. I stumbled across this inadvertent diptych in Google Books, it’s pp. 86-7 of P. Ch. Joubert’s 1844 addition to the Manuels Roret series, Nouveau manuel complet du fabricant et de l’amateur de tabac.

It’s beautiful, somewhere between the process-heavy, content-free abstraction of Walead Beshty and the reverential physical investigations of Abelardo Morell, with a bit of those weird Weegee funhouse mirror photos thrown in for good measure.

And yet they’re also entirely of their own time, place, and making.

A few years ago at John Connelly, my buddies Jonah Freeman and Michael Phelan showed some sweet prints of crumpled aluminum foil shot on a flatbed scanner. [Mitterand+Sanz has images] Which could be a great process here. But I’d really love to figure out how to create negatives from these scans and make up some big, old school silver gelatin prints. [thanks GF-R for the heads up on Morell]

Related from last October: Why is Google giving us the finger? [designobserver.com]

Google Image collection of Google Books Finger [via BoingBoing]

‘It’s An Inducement To Memory’

Giuseppe Panza di Biumo, interviewed by Christopher Knight in 1985 for the Archives of American Art:

DR. PANZA: Well, the connection between Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art was made through Rauschenberg, because if you look at Rauschenberg, you see also the sign of the painting. We don’t see only the collage, also the object, the real object. And for this reason, it was natural for me to arrive at the Pop Art. However, when the Rauschenbergs came into my house there was some people which was very interested, but very few, but some was very fascinated by the work by Rothko and Kline, and Tapies, and to see this kind of art so different, so vulgar, made with the objects which are really found by upsetting the container of the trash, was a scandal for these people. [Laughs.] But I felt a great interest in the work by Rauschenberg because I see from the nature of this details, a relationship to something which happened in his past. It’s an inducement to memory, the work of Rauschenberg. Are all the ties made with the connection to something real, which is fading away, because it’s a fact which happened in the distant past when perhaps the artist was young. The quality of this material, which became old because are perishable materials. The paper, the wood, the objects add this kind of distance to the memory, making the object stronger because is alive in the memory. Because it’s a matter of fact, but something which we have strong experience in the distant past, is by the memory in some way changed, became more beautiful, because lose reality and get more ideal reality. This process is very strong in the work of Rauschenberg, especially in the ones made in the fifties.

Just working my way through. Panza’s English doesn’t skim very well, but his descriptions of James Turrell installations are fantastic, some of the clearest I’ve ever read. For example, this account of a 1973 visit to a room in the artist’s house, which I confess, I’ve never heard of–is it a reference to the Main and Hill Studio installations in 1968-70 mentioned in Turrell’s bio?:

DR. PANZA: In Santa Monica, in his house, there was another room which was completely dark. This room was nearby a street corner, with lights in the middle of the street. One side of the room was overlooking a small road with a little track. The other side was looking at the main street with many cars passing through. And there was a lamps of public light nearby; there was some small houses nearby. And Turrell, at the end wall of this room, made holes which was possible to open and to close in different positions of the wall. Opening the hole was facing the streetlight, it was possible to have inside the room only the light coming from the red, the green and the yellow light, leaving [off] the light of the street.

MR. KNIGHT: Of the streetlight?

DR. PANZA: Yes, the streetlight. And the room was filled of, for some minutes, of a beautiful red light. And after, the yellow one. And after, the green one.

MR. KNIGHT: And it would change.

DR. PANZA: And closing this wall but opening another one, it was possible to see only the light projections of the cars which was passing fast in the main street. And this light was coming inside the room like a lightning, filling the room with very strong light, but for a very short time. And afterward disappear; the room became again dark. Opening another hole, it was possible to see only the car coming from the small street, and for some minutes the room was completely dark, but after, some small dim light was coming into the room stronger and stronger. This light had shape, and this shape was going around the room when the car was turning in the main street. And there was a completely different feeling of the light. And opening another one, it was possible to have only the light coming from the far away public light from the street, not the one nearby the house, but one very far. And this light was very dim, but was filling, in a very peaceful way, the room. It looks like the moonlight. It was giving the same kind of emotion, because was visible only the shadow of the objects inside. There was a confused notion of the volume of the space. The room was looking very much larger, almost endless, because there was almost no shadow, a very faint shadow. Everything inside the room was looking like having lost material quality, gaining some kind of ideal entity, which was no more earthly, but heavenly. Something very strange, very metaphysical. And there was a series of this experiences which was very beautiful, made in a very simple way, showing the quality of many kind of light.

This use of only found light, it’s like those seemingly pop/superficial pieces that use reflected light from TVs showing cartoons, like in the Mondrian Hotel’s elevator lobbies, crossed with a quintessentially Los Angeles mockup of the timeless/profundity of Roden Crater. Someone please tell me this still exists.

update: haha, of course not. It turns out it’s the building that used to be called the Mendota Hotel, and the works are his seminal, site-specific, Happening-like Mendota Stoppages. I’d always read Mendota as a studio, not a house [though it was, in fact, both.] Of course it is now a Starbucks.

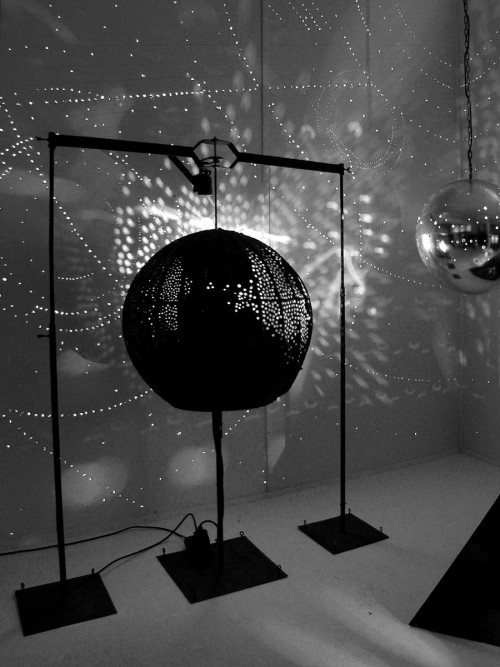

Otto Piene’s Light Ballets & Exhibiting In The Sky

Following on to their 2008 retrospective of ZERO, Sperone Westwater is exhibiting work by the group’s co-founder, Otto Piene. ” Otto Piene: Light Ballet and Fire Paintings, 1957-1967″ runs through May 22nd. [16 Miles has very nice installation shots.]

While I am stoked to see Lichtballet, 1961, above, the piece I’d most like to see, the silver sphere hanging on the right, is not in this show. This photo, by Günter Thorn, turns out to be of Lichtraum [obviously] from “Bilder, Objekte, Grafiken und Lichtraum,” an exhibition last winter at the Kunstverein Langenfeld.

Last year, the Pompidou had a cheeky, brilliant exhibition, Voids: A Retrospective, which consisted of nine empty galleries, each a different re-creation of an artist’s showing of a void. [John Perrault discussed the show at length in March 2009.] I feel I am now tiptoeing backwards into a similar project, a retrospective of artists’ shiny silver balls.

Piene was creating these Light Ballet pieces while the Echo I satelloon was orbiting the earth, its reflection visible to the naked eye. He exhibited them in New York in November 1965, at the Howard Wise Gallery. Sperone has reprinted Piene’s essay from the small catalogue to that show. Here is an excerpt:

In 1959 I played the light ballet with hand lamps, in 1960 I built the first machines, in 1961 they appeared in large darkened rooms at exhibits and in museums: one object, two objects in a large hall, a waste of space, an elimination of conventional attitudes about quantity. The farther the distance between the projecting device and the light-catching confines of a room, the larger are the light forms. And when they are large, the claustrophobia caused by the ordinary cubicity of our interior spaces recedes.

…

My endeavor is twofold: to demonstrate that light is a source of life which has to be constantly rediscovered, and to show expansion as a phenomenal event. Everything is striving for larger space. We want to reach the sky. We want to exhibit in the sky, not in order to establish there a new art world, but rather to enter new space peacefully–that is, freely, playfully and actively, not as slaves of war technology.

A rubber skin, helium and the wind, light, electricity and fireworks seem to me excellent media. The revolving beam of a lighthouse and a balloon in the air are more convincing sculptures than the big chunks that are so hard to move. Calder’s mobiles can be taken apart. Our objects ought to be inflated or ignited or projected. And environments? As far as a laser beam reaches. Are the jet pilots who write vapor trails in the sky the artists of our time, as Gothic stone-masons were the artists of theirs?

Despite their similar shapes, there is one essential difference between Gothic cathedrals and rockets: a cathedral seems to soar, expressing the yearning of its builders to ascend to heaven; a rocket does soar. The same technical difference exists between traditional sculpture and my objects. Previously paintings and sculptures seemed to glow, today they do glow, they are active, they give, they do not merely attract the eyes, they do not merely express something, they are something. A filament glows and warms, a painted halo only reflects light. Energy in a contemporary form produces the living media. Is the filament in itself a piece of art?

Transformation still has two meanings, one technical, one spiritual. He who leaves his house leaves the light on to make it appear inhabited.

Previously: Otto Piene et al’s Centerbeam & Icarus on The National Mall

Whoa, Autoprogettazione X Artek Mashup

HUGE news from on the Enzo Mari autoprogettazione X [Scandinavian Furniture Giant] mashup front:

The Finnish manufacturer Artek will announce ‘sedia 1- chair,’ “the first object from Mari’s thought-provoking project ‘autoprogettazione’ to go into production” with the company. “the first”!

Like the original “manufacturer,” Simon International, run by Dino Gavina, Artek will sell you a stack of pre-cut pine boards, some nails, and the instructions. Look at those wide boards, they’re built up, just like the tabletops on certain other autoprogettazione pieces I’ve seen from the region.

For the full press release/preview, and more shots of Mari building his own damn chair, thank you very much, go to designboom. [thanks andy]

Previously: the Enzo Mari X IKEA mashup saga

Cage Match

I was reading Calvin Tomkins’ 1963 New Yorker profile of abstract sculptor Richard Lippold, who was a favorite of the International Style and High Modernist architecture crowd. Depending on your mood, Lippold’s giant, intricate, and ambitious metal & wire works were breaking Important Art of The Future out of the twee confines of the gallery and museum. Or he was making quintessentially aggrandizing corporate lobby art, built-in Bertoias for barons and bankers.

Most of the article tells the crazy story of the creation and installation of Lippold’s best-known work, Apollo and Orpheus, which tumbles through the lobby of Philharmonic Hall [now Avery Fisher Hall] at Lincoln Center. But this remarkable bit is from May 1962, and the making of his most-seen work, The Globe [later changed to Flight], the shimmering, golden wire sculpture in the Vanderbilt Avenue lobby of the Emery Roth, Gropius & Belluschi’s Pan Am building [now Met Life] behind Grand Central Station:

Most of the article tells the crazy story of the creation and installation of Lippold’s best-known work, Apollo and Orpheus, which tumbles through the lobby of Philharmonic Hall [now Avery Fisher Hall] at Lincoln Center. But this remarkable bit is from May 1962, and the making of his most-seen work, The Globe [later changed to Flight], the shimmering, golden wire sculpture in the Vanderbilt Avenue lobby of the Emery Roth, Gropius & Belluschi’s Pan Am building [now Met Life] behind Grand Central Station:

Lippold was also engaged at this time in a curious negotiation with his Pan Am patrons. He had discovered that the building had been wired throughout for Muzak. Muzak has long been one of Lippold’s particular abominations, and, with his customary directness, he voiced his dismay at a cocktail party given by the late Erwin S. Wolfson, the New York investment builder who had largely conceived and financed the Pan Am Building. If the building had to have music at all, Lippold suggested jokingly, why not let him commission some contemporary music by John Cage? Wolfson floored him by saying, “Go ahead.” At the time, Lippold told a friend, “Wolfson belongs to the new breed of industrialists who respect artists. He trusts them, he’s willing to let them do what they want without interference. But, my God! Think of it! Cage is still too avant-garde for the concert halls, and here’s a chance for his music to be played to an audience of thousands and thousands a day! It will be the first time in history that music has been commissioned to go with architecture–or at least, the first time since the medieval cathedral Mass.” Wolfson said he would take care of persuading his board of directors, and Lippold got Cage started thinking about the project.

Not sure what’s more unsettling: the “new breed of industrialists” gladhanding, or the Richter-meets-Kinkade-style paradox of Cage doing Muzak.

But whaddya know, the project went forward. As one might have expected of an artist working in ambient sound, Cage had invested years of thought in solving The Muzak Problem. In his 1998 article in The Musical Quarterly on Cage’s approach to silence, Douglas Kahn makes an interesting analysis of Muzak’s connection to the development of Cage’s best-known composition, 4’33”. In a lecture he gave in 1948, four years before creating 4’33”, but which he never republished, Cage talked about another silent composition, Silent Prayer:…which would consist of 3 to 4-1/2 minutes of sustained silence (the maximum time being just three seconds short of 4’33”) to be played over the Muzak network.

Unlike the silence of 4’33”, in which not playing is the means for the audience to hear the sounds surrounding them, Kahn wrote that Cage saw Silent Prayer more like an intermission, a “reprieve” from Muzak’s unobtrusive yet pervasive performance.

He also makes a fascinating point about Duchamp’s readymades and the length of Silent Prayer [and, by a 3-second extension, 4’33”], which was based on the standard duration of commercial music.

Back to Pan Am. With the technical assistance of Bell Labs [Kluver? Anyone? Aha, Max Matthews. see the update below.] Cage’s Muzak project had made it to the “elaborate presentations” stage, and by August 12, 1962, the idea was fully developed enough for Raymond Ericson to report the details in the Times:

[Cage] decided to “make use of the things that were right there” in the lobby. This was to include the supply of Muzak, for which Pan Am had a contract; the necessary speakers in the walls, and a set-up of television screens with photo-electric cells for keeping an eye on the passers-by.

Mr. Cage devised a system whereby the people going through the lobby would activate the photo-electric cells. These in turn would release the Muzak music, which would become pulverized and filtered in the process. Even people getting in and out of elevators would have a part in producing the sound. Since the cells would never be activated in the same way, the results would be constantly in variation.

Rather than underscore the pervasiveness of Muzak by giving its unwilling audience a temporary reprieve, Cage would make the pedestrian throngs aware of their collective selves, by giving everyone the power to toggle the Muzak off and on.

Unfortunately, Wolfson, the new breed of industrialist, died in July, and the reason the Times was writing about Cage’s piece was because the old breed of board members had just rejected it. “As one vice president said: ‘The American business man and the esthete do not always see eye to eye.” Really.

Ericson’s kicker makes me want to head up to Bard and start digging through the archive at the John Cage Trust: Mr. Cage does not feel particularly disappointed in the failure of his plan. He believes his ideas are sufficiently in the air to be acted on someday.

UPDATE: Apparently, in the Spring 2008 issue of Representations, the University of California Press Journal, Herve Vanel wrote an article about Cage’s relationship with Muzak titled, “John Cage’s Muzak-Plus: The Fu(rni)ture of Music.” which I would buy for something less than the $14 UCP is asking. [UPDATE UPDATE: it seems like I’m the only guy without a subscription, better get on board. Thanks to Douglas and Brian for loaning me their pdf version of Vanel’s article.]

Some interesting finds from Vanel’s paper: Cage had been thinking about a Muzak composition, called Muzak-Plus, in 1961, which I would imagine his friend Lippold would have known about. It was Bell Labs computer music pioneer Max Matthews who collaborated with Cage on the Pan Am Building, not Billy Kluver. But Matthews’ photo-electric switch and mixer design apparently resurfaced as a dance device in 1965 when Kluver participated in Variations V with Cage, Merce Cunningham, David Tudor, and Stan VanDerBeek. Which is like the best Merce & John clip on YouTube.

On the downside, is that renovation related to the 2005 purchase of the Met Life building by Tishman Speyer? Or have security retrofits destroyed whatever spatial integrity the lobby had? Do we know need to wonder what a John Cage piece based on the random, unimpeded flow of crowds into a lobby would sound like before and after September 11?

Wait, ‘Highly Developed Dutch Cartographic Traditions’?

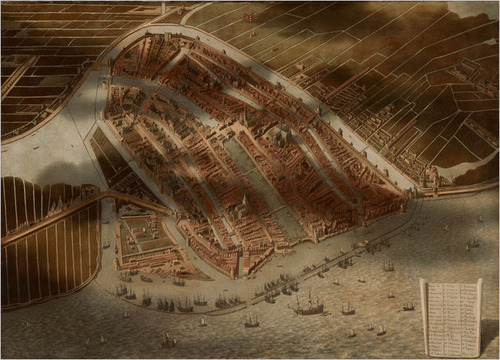

From Ken Johnson’s thrilled NYT review of “Pride of Place: Dutch Cityscapes of the Golden Age,” which was at the National Gallery last winter:

The painters of the golden age in Holland brought the city onto center stage and made the cityscape a genre unto itself.

This urban motif evolved out of highly developed Dutch cartographic traditions. Large, intensively detailed maps included in the show suggest an almost obsessive preoccupation with geographical facts.

One of the strangest pieces is a painting of Amsterdam, seen as if from a hot-air balloon. Seemingly every building, street, canal and boat in town is carefully rendered, and shadows of clouds pass over the city and surrounding fields, creating an almost surrealistic mix of the real and the schematic. (Aerial views from Google Maps come to mind.) Made in 1652 or later by Jan Micker, it is a copy of a similar work from 1538 by Cornelis Anthonisz.

I confess, I liked the exhibit, but at the time I was not sufficiently attuned to the highly developed cartographic traditions of the Dutch. And anyway, the oblique angle on that bird’s eye-view map look more like Bing to me.

At the Height of Power for the Netherlands, the City in Glorious Detail [nyt]

On Thomas Ruff At Aperture

Joerg has an interesting recap of Thomas Ruff speaking with Philip Gefter a couple of weeks ago at Aperture.

I’m a fan of several of Ruff’s series of work–and distinctly not a fan of others, but hey. Here’s a bit about the Sterne/Stars photos, one of several of Ruff’s appropriation series:

Ruff has worked a lot with images that are not his own, be it the stars, the newspaper clippings, or the images of machines he found on a set of glass plates he bought. Each of those series centers on investigating the essence of authorship or reality in photography: The stars he picked as the most objective photographs one could possibly produce (as an astronomer I’m not sure I agree with this)…Here’s a photographer who not just decided to play with images to have them fit his artistic vision – instead, it’s a photographer who has looked at what photographs can do from a very large number of angles…

I love that Joerg’s an astrophysicist/photographer.

Though Ruff uses contemporary plates from an entirely different survey form a different observatory in an entirely different way, his Sterne are definitely an inspiration for my plan to show and reprint the NGS-Palomar Observatory Sky Survey.

Also an antecedent, if not a direct influence: Ruff’s Jpegs series, which blows up low-res web-scavenged images to grand, pixelated scale. Even though the discussion was scheduled to promote Gefter’s new book and the limited edition of Ruff’s Jpegs catalogue [published by Aperture, with an essay by my buddy Bennett Simpson], the jpeg images didn’t make it into Joerg’s notes.

Neither, alas, did much input from Gefter. He’s a very attuned guy, and it was great to work with him on some of my pieces for the Times. So basically, I’m a 360-degree fanboy over this event, and am hoping Aperture will indeed post video of it soon. Or ever.

update: aha, they did. right here. Thanks again, Joerg.

Ein Abend mit Thomas Ruff [jmcolberg.com]

Thomas Ruff: Jpegs