Walter Hopps’ 1991 exhibition at The Menil, Robert Rauschenberg: The Early 1950s, changed my art life, basically. Bob and Cy trekking around Italy. Bob and John and Merce collaborating. Bob and Jasper, whoa. Did not hear much about that at BYU’s Art History Department.

Anyway, Merce Cunningham and John Cage’s art collection is now being sold at Christie’s to support the late choreographer’s foundation. Some of the stuff is fantastic, and some is slightly precious.

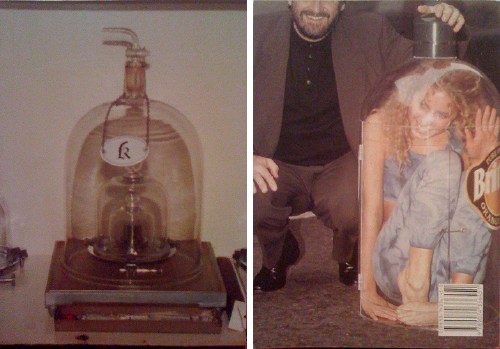

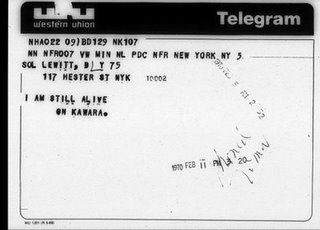

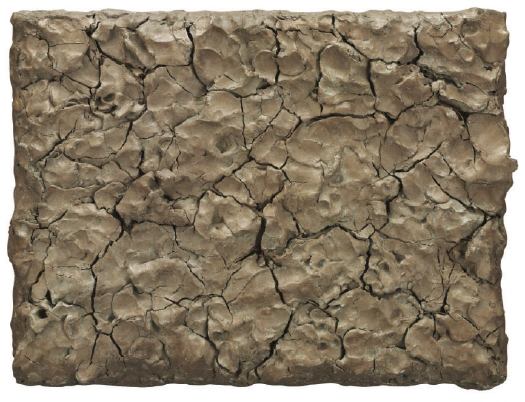

Here’s Clay Painting (For John Cage and Merce Cunningham), Rauschenberg’s 1992 recreation/replacement of the seminal 1953 work, Dirt Painting (For John Cage), which the artist borrowed for a retrospective and never returned. He was working on it when Cage passed away in 1992.

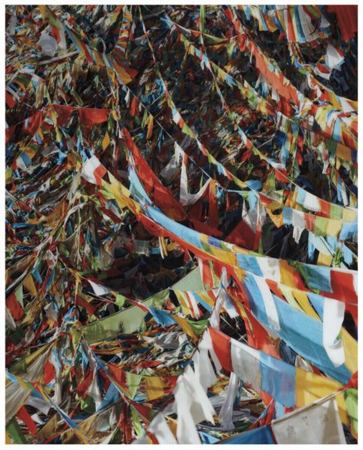

Rauschenberg’s original dirt painting was created after his visit to Alberto Burri’s studio in Rome. But while Rauschenberg has acknowledged Burri and his material aesthetic as a central influence on his later Combines, the original dirt painting, with its notion of growing mould defining the form and composition of the work, probably owes more to the influence of a work like Marcel Duchamp’s Dust Breeding of 1920. Duchamp was an important presence behind the creative thinking of both Cage and Rauschenberg who, in 1953, collaborated on a number of projects, most notably perhaps their Automobile Tire Print — a printed drawing made by Cage driving a truck with a painted tire over a series of paper pages laid down by Rauschenberg. In this later dirt painting, Rauschenberg has chosen to use unfired clay as the material for this newer version of his earlier self-defining painting. In this work which, like many of Cage and Rauschenberg’s works is dependent on the passage of time for its resultant form, the cracks that have appeared in the dried clay this time recall more closely the later Cretti paintings made of earth that Burri was to make in the 1970s.

Can you believe Cage driving the car? Automobile Tire Print is like a Zen scroll painting, action painting, a Newman zip, and Pop Art stunt all in one.

Nov. 10, NYC, Lot 5: Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled, 1953-1992, est. $200,000-300,000 [christies.com]

Also: Lot 6: No. 1, 1951, a 50+yr black painting colabo between Rauschenberg and Cage, est. $800,000-1,200,000

Related: Alberto Burri’s Cretto on greg.org