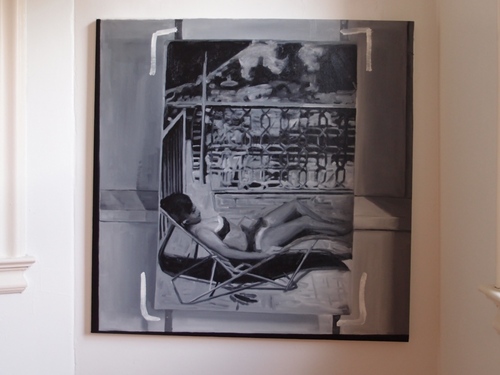

OK, wow, so this is a music video by Michelangelo Antonioni, one of the first/few things he shot on video. It’s a song called “Fotoromanza” from “Puzzle,” the first hit album by the Italian pop singer Gianna Nannini. As you can tell just by looking at it, it’s from 1984:

Here is Antonioni discussing the music video with Aldo Tassone, in a 1985 interview that first ran in the French cinema magazine Positif, but which is published in English in The Antonioni Project’s 1995 compilation, The Architecture of Vision: Writings and Interviews on Cinema

You have shot a feature film and a few shorts on video: how did you find that experience?

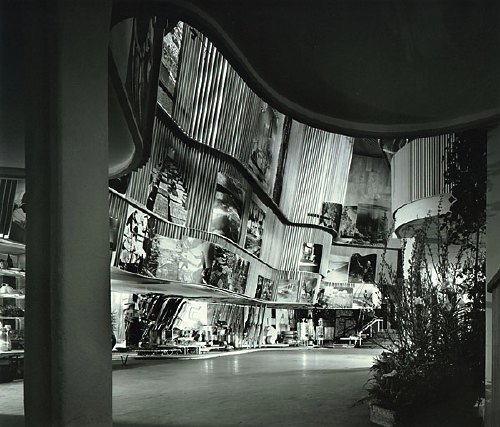

It was a very interesting experience, even if at the time, in 1980, the techniques of transferring videotape to film weren’t highly developed. The copy–on tape–of The Mistery of Oberwald is very beautiful. I don’t understand why the French television didn’t distribute it more widely. In America, the commercial I shot for the Renault 9 [!? -ed.] was judged the best commercial of the year. It cost eight hundred million lire to make. For the video I shot for the rock singer Gianna Nannini (the song is called “Fotoromanza”), I only had forty million lire to work with–and in fact I don’t much like the end result. To make intelligent videos you need serious money.

I think video is the future of cinema. To shoot on video has so many advantages. To begin with, you have total control over color. The important thing is to work with a good group of technicians. Video reproduces what you put in front of the camera with almost total fidelity. The range of effects you can achieve is not even comparable to cinema. In the lab, you always have to compromise. On video, in contrast, you have complete control–you always know where you are because you can play it back at any stage, and if you don’t like it you can redo it.

The Internet tells me this is Antonioni’s spot for the Renault 9. Which looks to me like at least 600 million of those lire went to Jacques Tati:

Which, apologies to the professore, is only the second best driverless Renault commercial I’ve seen.

Sergio Leone and Ennio Morricone drop mic and leave the stage.

[via @filmstudiesff and @Coburn73]

[2022 update: these links have been updated where possible, but at the moment I can’t find Antonioni’s Renault commercial online. Fortunately, this is the only bad thing to have happened on or related to the internet in the intervening 10 years.]