Ro/Lu is en fuego these days, in case you didn’t know, and I’ve been lucky enough to get warmed by their fire.

First off, they’ve been doing this Simple Chair project, an exploration of how and where our stuff is made. It’s making its second appearance at Mass MOCA. I was planning to just write about it more when I saw the publication [to which I contributed a brief article of my Enzo Mari X Ikea table project], but Ro/Lu just keeps on doing stuff, so I can’t sit silently by.

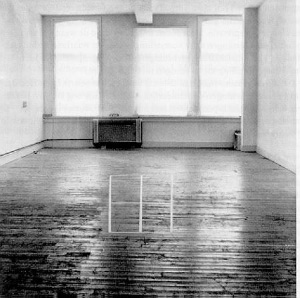

And then, as if reading my mind–or my blog drafts, or maybe communicating telepathically with me through the minimalist/modernist/design/art ether–they posted a link to an awesome-looking 1980 exhibition at The Renaissance Society in Chicago, “Objects and Logotypes: Relationships Between Minimal Art and Corporate Design”.

Whoa. It’s fascinating to see how Minimalism, modernism, and corporate branding were perceived and presented thirty years ago. They all feel digested and processed now, but I get the sense that what curator Buzz Spector is talking about in his essay is not quite the same thing we use those terms for today.

Which may be a way of saying I take issue with many of Spector’s definitions and points, but I’m not quite able to articulate why I think he’s wrong. I mean, I can say that I think Greenberg’s Minimalism-as-“mannerism” does not seem related at all to the principles of usage in corporate visual design. Or that the ubiquitous, homogenizing proliferation of a corporate logo seems like the diametric opposite of Robert Morris’s sculptural gestalt, not its twin.

But Spector’s show still seems like an interesting, important first step for the coming revisiting of Minimalism. And siting avant-garde art practices in parallel to mid-century corporate marketing is pretty compelling to think about. And I really like the idea Spector hangs his show on, that these designers and artists are alike in conflating form and value, i.e., that they “reflect a common faith in the efficacy of form as a means of restructuring society through public exposure to works executed within particular systems of use.”

As I sit here in the middle of a mild obsession with the Netherlands government’s new, painting-inspired rebranding and centralized visual identity system, this idea feels as relevant as ever.

So thanks, Ro/Lu!

Tag: Enzo Mari

Enzo Mari X IKEA + 6-Year-Old =

So I guess you could argue–and you wouldn’t be completely wrong–that no matter how many coats of hand-rubbed varnish it has, no matter how carefully calculated its design, or how flush its finishing nails, how stainless its many steel screws, a dining table which a six-year-old girl can snap apart like a pair of ramen truck chopsticks cannot, in the end, truly be considered a success.

But anyway, it’s not worth arguing, because that’s what happened the other day. And it’s not important or even relevant to discuss exactly how it happened, or who did it. Because obviously, it’s my fault. In fact, if the Enzo Mari X IKEA autoprogettazione table survived a day in our house, it’s only because our family and regular visitors were living in fear, subjected to a constant, low-level psy ops campaign of tense looks and warnings, with suspected leaners getting regularly guided toward the table’s side seats and away from the cantilevered ends.

Because the top clearly broke on Ikea’s butt joint, and not my own is of little comfort; it broke where the fulcrum was–the base. I knew it would/could happen when I decided to make my table top from horizontally built up Ivar shelving instead of the other two options I had: 1) tracking down the original, 200cm long Ivar shelves that had just been discontinued when construction began, or 2) using the thick, pine slab head and footboards from a king-size Mandal bed. The former, I nixed because I decided that building a table from discontinued Ikea parts might hinder the vast revolution in autoprogettazione-inspired Ikea hacking that would surely follow the debut of my project. The latter, well, the bed frame came already finished, and that felt a little like cheating.

Now, of course, with a card-table sized dining table, I’m more than ready to compromise. But Ivar long shelves are still discontinued, and now, it turns out, so is the wood-intensive Mandal bed, which has been redesigned to use no headboard, or a weird, slatty thing you mount on the wall.

That means I’m going to need to re-create the table top as-is, and reinforce it underneath, and hope that it holds. Or I’ll replace it entirely, probably with some slabs of sick, slick, ultra-deluxe 500-year-old sinker pine from the bottom of some icy river somewhere. Either way, I’ll be back in the basement, varnishing something soon.

Previously: The making of an Ikea X Enzo Mari table, in many chapters

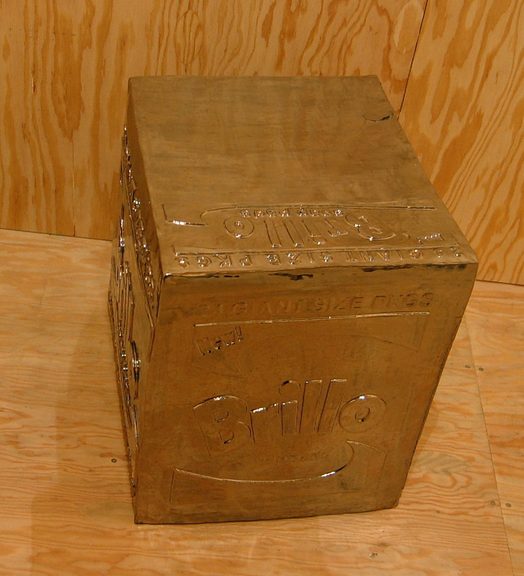

Stainless Steel Brillo

So awesome. Is there nothing that can’t be made better by Rirkrit chroming the hell out of it?

Fear Eats The Soul, Rirkrit Tiravanija, through April 16 at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise [gavinbrown.biz]

Awesome photo of chrome stainless steel Brillo Box and wok, one of many by Andrew Russeth [16miles.com]

Previously: Enzo Mari X Rirkrit Tiravanija

Extensive Brillo Box coverage on greg.org

‘Do-It-Yourself Existential Individualism’

Frieze’s 20-year retrospective of itself continues apace, and wow, it’s like running into an old flame on a train platform.

I hadn’t thought about Daniel Birnbaum’s 1996 essay, “IKEA at the End of Metaphysics” in years, but wow, it’s just all flooding back.

From a Heideggerian perspective IKEA best sellers such as ‘Billy’, ‘Ivan’, and ‘System 210’ do not represent a corruption of everyday life, but have merely formalised what is already there; the IKEA catalogue only makes the tendency towards uniformity more conspicuous. Heidegger’s global ‘levelling’ is not a critique of the common forms of everyday life as such, but of their passive acceptance. At the end of metaphysics, levelling is complete – no one questions the catalogue.

Obviously–well, now it’s obvious, anyway–my own Ikea X Enzo Mari mashup project has its origins in the critical perspective of the company and its ideology which Birnbaum mapped out 15 years ago, and which I absorbed.

Also, I’m reminded how I miss Jason Rhoades.

IKEA at the End of Metaphysics [frieze.com/20/ via ronald jones]

Why Enzo Mari Is Not Your Capitalist Art Market Stooge

Looking at objects and vintage photos in isolation, it blows my mind that Enzo Mari is somehow not a famous, formative artist, but only [sic] a designer. How did that happen? Did he make all his work in secret? Did he never try to show it? Did he just never sell it? Or enter an art dialogue? Did he get muscled out by Fontana and Manzoni for the parochial art world’s Seminal Sixties Italian Artist slot?

But you know what, he was a famous artist, or at least he showed his art for a long time in a series of prominent places, in exhibitions that were considered important and are now considered historic, even. And yet even as some of those events are being revived, revisited, and reemphasized, Mari’s involvement in them is not.

I was going to solve this mystery, and find the answer, using the two dozen or so browser tabs I’ve accumulated in the last 24 hours. But you know what, I think I’m just going to cut ‘n paste my links and let the info sort itself out.

Thing is, there probably ARE people who know exactly how or why Mari the Artist’s career or influence is the way it is; and it’ll be easier to try and track them down rather than engage in armchair speculation. Or I’ll just pigeonhole Hans Ulrich in Miami, either way.

So here’s what I’ve got:

Continue reading “Why Enzo Mari Is Not Your Capitalist Art Market Stooge”

Enzo Mari, Artist

Look, I don’t doubt that Enzo Mari hates the art world as much as he hates design. Even more, probably, since he’s a faithful communist in an era when–Picasso bedamned–it’s really hard out there in the art market for a Red.

But.

Mari is just as resolute about not distinguishing between art and design. And he makes art. Objects. And has, for over 60 years.

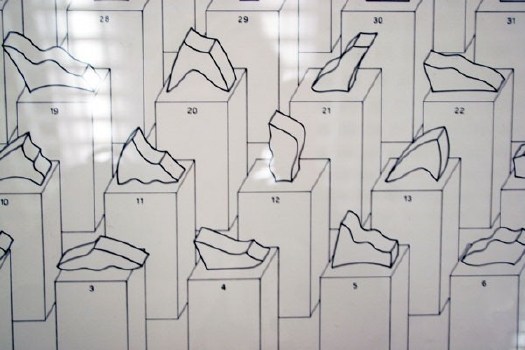

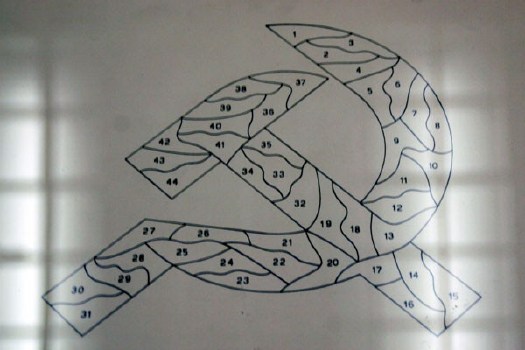

Just check this out, 44 valutazioni, a suite of 44 abstract sculptures Mari exhibited at the 1976 Venice Biennale.

When they’re listed in order the title from each piece becomes the line in a poem by Francesco Leonetti, and when they’re assembled, well, hello, comrade! A hammer and sickle! Old school.

installation images of Mari’s GAM Torino show from designboom‘s extensive galleries.

We’ve brought Group ZERO back, right? At some point, the art world, and art history, are going to have to take Mari’s artworks into account, because, damn. He was doing minimalism and seriality a full decade before Judd and Lewitt.

What are these struttura of which no one really seems to speak? [Except here, in a 30-year-old Italian monograph titled, naturally, Enzo Mari, Designer, which includes a chapter on Mari’s “research of form” and these “instruments of perception”?]

1956, struttura no. 301? Really? The only thing more eyebrow-raising than your date is your estimate: EUR6-8,000 at Dorotheum.

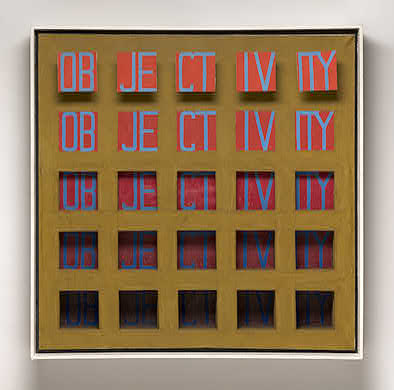

[OK, so maybe six years before Lewitt. Here’s his 1962 painting Objectivity at the National Gallery of Art:]

[I guess I was thinking of Lewitt’s 1967 Dwan Gallery show–and exhibition poster/print–and his 1968 photo object, Schematic Drawing for Muybridge, as seen here in flickr user clarkvr’s snap:]

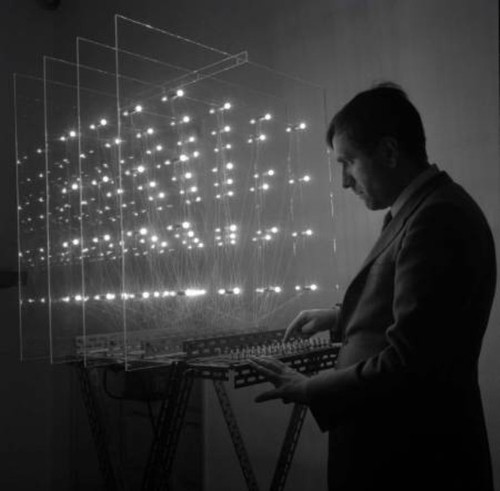

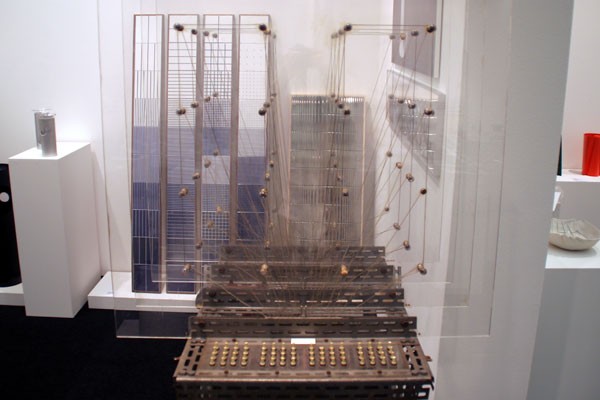

But then there’s kinetic art, too. And what in the world is this? Omaggio a Fadat, 1967, a machine for “creating virtual volume” made from 64 lights, switches, steel, and perspex?

I mean, I know he had a show last year [2008-9, actually] at GAM Torino, but even if you call it “The Art of Design” and include a bunch of awesome sculptures, shoehorning 60 years of stuff into one gallery of a municipal museum is not exactly a retrospective. Look at this Omaggio, for example, if you can:

Also, he curated the show himself. Or designed it himself, using objects selected by his friends. Believe me, I know DIY’s his big thing, but seriously. It’s not like Mari’s an unknown quantity, and his influence is readily acknowledged–hell, he’s a huge influence on me, and building his autoprogettazione table as an art exercise, then devising an exhibition based on his principles of authorized reproducibility have kept him on the top of my mind for much of the last four years, at least–but he seems relegated to the designer’s corner, and his artwork–oh how sweet, the designer makes art, too!–with him.

Or am I missing something? Please say yes. [hmm, after some market-related digging, Mari’s problem may be that he makes Italian art, and only two Italian artists are allowed to become well-known outside of Italy each decade. Not much to be done about that, I guess.]

Sedia Veneziana, Chaise Bordelaise

via la_biennale

So Venice is not a total bust. Raumlaborberlin have installed their 2006 mobile inflatospace sculpture, „Das Küchenmonument,” in the Giardini.

And next to it is The Generator, an on-site workshop for knocking together “sedia veneziana,” which are not just autoprogettazione-style chairs…

via br1dotcom

they’re “future particles of the generator-space-structure,” modular building elements of both social space and structure. autoprogettazione stacking chairs. Awesome.

Which, of course, is related to their exhibition for Arc en Reve in Bordeaux last year, “Chaise Bordelaise.”

“Chaise Bordelaise” consisted of a 3x3x1m pile of pre-cut, reclaimed lumber, instructions, and some tools. Visitors made some chaises, then took them home.

It’s basically an Enzo Mari x Felix Gonzalez-Torres mashup. If greg.org had tags, this post would be giving me a tagasm right now.

Raumlaborberlin: what’s up? exhibitions [raumlabor.net via archinect]

Chaise Bordelaise [raumlabor.net]

related: proposta per un’ auraprogettazione

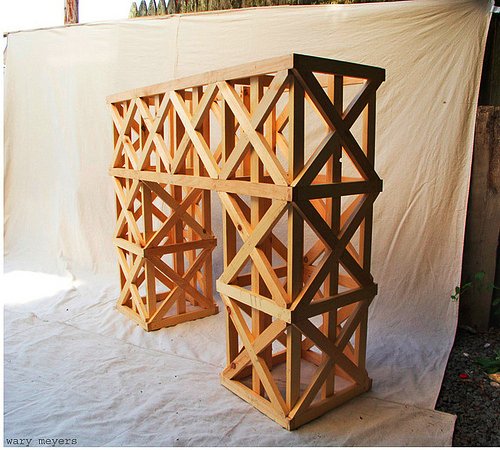

Wary Mari

And thus we see the painful difference between meaning to buy Wary Meyers’ awesome-looking design project book Tossed and Found and actually buying it. I would have been inspired by their Enzo Mari autoprogettazione-esque mantle many months ago. What progettazione have I not thought of in that time? I’ll never know.

Progettazione 1×2 [warymeyers]

Non Realizzate: Proposta Per Un’Auraprogettazione

Apex Art just announced that Courtenay Finn and Gary Fogelson were selected for this year’s open curating slots. Finn’s proposal uses a work by Bruce Nauman as a jumping off point for a show about “the role of reading in artistic practice.” Fogelson’s will tell the incredible-sounding history of alternative, arts, and experimental filmmaking shown in the 1970s on Boston’s WBBI TV. Congratulations to both of them, and get cracking, time’s a wastin’!

I’d had an idea for a show percolating for a while, so I submitted it. As I re-read it now, it’s fascinating how much of it is stuff I’ve blogged about over the last couple of years. In a real sense, the blogging process was central to the development and coalescence of the show’s ideas, if not for the actual proposal, which I wrote up and submitted anonymously, as Apex Art requires.

It tied for 45th place out of 320 entries. 86th percentile, which is alright, I guess, in a B-show kind of way.

Anyway, it was inspired, as the title suggests, by Enzo Mari. It challenges the common conception of aura by applying Mari’s autoprogettazione reproduction strategy to instructions-based art practice.

And because it also includes references to the great gatherer of Unrealized Projects, Hans Ulrich Obrist, I thought I’d go ahead and share my proposal here. If you’re one of the 40 international, anonymous judges who rated it less than 4/5, I do hope you’ll drop me a line and tell me what might have improved it for you.

Many thanks to those folks who gave me feedback and art historical suggestions on the idea as I was putting it together, too. I don’t want to sound namedroppy–until we polish this bad boy up and put on this jargon-laden, Stingelpainting party somewhere else, then I’ll be thanking you often and loudly, I’m sure.

Proposta per un’auraprogettazione

A project for making easy-to-assemble furniture using rough boards and nails. An elementary technique to teach anyone to look at present production with a critical eye. (Anyone, apart from factories and traders, can use these designs to make them by themselves. The author hopes the idea will last into the future and asks those who build the furniture, and in particular, variations of it, to send photos to his studio…) – Enzo Mari, Proposta per un’autoprogettazione, Duchamp Center, Bologna, April 1974

Walter Benjamin’s concept of aura is commonly understood as a quality that distinguishes an original art object from its mechanical reproduction. Recent alternative readings [Samuel Weber, 1996], particularly of cinema–Benjamin’s archetypal medium of modernity–consider aura as something not lost in (re)production, but instead contingent upon it. Aura is generated through contextualized reception via dispersed, multiple ‘originals,’ as literary or musical aura is transmitted via books and scores.

When coupled with Benjamin’s functional reconfiguration of the distinction between author and reader [“through a highly specialized work process…the reader gains access to authorship”], production of an auratic artwork at a [spatial/temporal] remove from the artist herself becomes feasible. The instruction performs such a distancing function.

From Moholy-Nagy through Lewitt, artists have used instructions and plans to challenge the privileging of gesture and authorship. The emergence of Conceptual art saw the concurrent normalization of instruction-based practice and the “dematerialization of the art object” [Lucy Lippard, 1973].

Lippard’s own seminal exhibition 557,087 (Seattle, 1969) was executed remotely using artists’ instructions, which comprised the show’s catalogue. Similarly, Do It (1993-) an ongoing exhibition/archive by Hans-Ulrich Obrist, solicits, executes and disseminates instructions from contemporary artists. [“With Do It in hand, you will be able to make a work of (someone else’s) art yourself.”]

Despite their critique of object/market complicity, instructions are regularly sublimated by capitalist constructs [i.e., editioning, certificates of authenticity] that reassert control and facilitate commodification.

Authorization thus emerges as a crucial and highly contested point of inflection/exchange for instruction-based work. Only five of 168+ instructions in Do It generate objects. One, a Felix Gonzalez-Torres candy pour (1994), was problematized when the artist’s catalogue raisonné [Cantje, 1997] reclassified it as “non-work” and reconfigured fabrication authority only for Do It‘s curators, not its audience.

A more conceptually robust corollary is art that applies a model exemplified by the Italian designer Enzo Mari, whose 1974 exhibition/catalogue, Proposta per un’autoprogettazione, (Proposal for a self-project) included not just blueprints for making 16 pieces of furniture, but explicit authorization to do so.

Mari’s autoprogettazione structure synthesizes Benjamin’s potential for multiple, auratic originals with the critical empowerment of readers-qua-authors, consumers-qua-producers, viewers-qua-artists.

Auraprogettazione will be the first ever survey of this distinctive, exceptional genre: auratic objects, fabricated by whomever, in accordance with artists’ published instructions and authorization. Preliminary research has identified consonant works–painting, sculpture, photography, assemblage, clothing–by at least eleven artists: Daniel Buren, Jan Dibbets, Stephen Kaltenbach, Lia Maisonnave/Ciclo de Arte Experimental, Yoko Ono, Tobias Rehberger, Rudolf Stingel, Joep van Lieshout, Franz West, Zhuang Da, and Andrea Zittel.

Alongside the ‘originals’ exhibition, the gallery may be activated as a site of open, facilitated art production, or as an aggregator/repository of audience-made originals. Additional artists may be solicited to create new, permissioned, instruction-based work. And as with Mari’s original, Auraprogettazione‘s publications in print and online will propagate instructions for the exhibited works.

Whoa, Autoprogettazione X Artek Mashup

HUGE news from on the Enzo Mari autoprogettazione X [Scandinavian Furniture Giant] mashup front:

The Finnish manufacturer Artek will announce ‘sedia 1- chair,’ “the first object from Mari’s thought-provoking project ‘autoprogettazione’ to go into production” with the company. “the first”!

Like the original “manufacturer,” Simon International, run by Dino Gavina, Artek will sell you a stack of pre-cut pine boards, some nails, and the instructions. Look at those wide boards, they’re built up, just like the tabletops on certain other autoprogettazione pieces I’ve seen from the region.

For the full press release/preview, and more shots of Mari building his own damn chair, thank you very much, go to designboom. [thanks andy]

Previously: the Enzo Mari X IKEA mashup saga

On Reading Auras

As you can guess from the mentions of Sherrie Levine, I’ve been studying the issues around copying and reproducing and originality and authorship. And whenever you do that, Walter Benjamin comes up, specifically his concept of aura.

Basically, it’s what an original work of art has that a reproduction doesn’t. Except when it does. It’s what declines or disappears in the process of mechanical reproduction–especially in the cinematic process, which interested Benjamin greatly–but then it comes back sometimes. Somehow.

Just in case quoting or arguing Benjamin at length is tedious or pretentious to the Twitterized reader, I’m putting a few quotes and sources after the jump, for my own reference later. They are:

Sherrie Levine

John Perrault

Samuel Weber

Grant Wythoff

Miriam Brantu Hansen

Lindsey Adelman’s Autoprogettazione Chandelier

I’ve recently stepped up my search for more examples of objects that resonate with Enzo Mari’s autoprogettazione model: artists and designers who offer not just the non-authorial conceit of “made by anyone,” but “permission to make it yourself.” It’s a surprisingly fine filter that keeps a lot of nominally instruction-based pieces off the list.

Anyway, I’ll make an open plea later. Right now, though, I’ll just give NY designer Lindsey Adelman a huge high five for publishing her “You Make It” chandelier. Adelman’s main practice is creating intensely produced chandeliers and lighting made from custom, modular hardware systems and handblown glass. They’re several thousands of dollars, and it shows.

Which makes it remarkably easy for Adelman to be so generous with the level of detail she offers on technique and parts sourcing for a $120 You Make It option; despite the beauty and conceptual similarity, there is no mistaking the one product for the other.

You Make It Chandelier [lindseyadelman.com via @ianadelman]

Related: Enzo Mari X IKEA mashup, ch. 4: Finish Fetish

Enzo Mari X IKEA Mashup, Ch. Last

home stretch, from Thanksgiving 2007 to Thanksgiving 2009.

And it is done. [more pictures here]

A quick recap:

An EFFE table based on a 1974 design by Enzo Mari, but made entirely from unfinished pine components of Ikea’s Ivar shelving system. The vertical and diagonal elements are the square corner posts. [Some revisions were made mid-construction.] Horizontal elements are the pre-assembled shelving side trusses. [The center truss uses two trusses intact, while the end trusses use disassembled pieces.] The top is glued up from four Ivar shelves, which are braced underneath. [compare to Mari’s original design below.]

Though Enzo Mari’s original design calls for the low-grade pine to remain untreated, I decided to finish the entire thing with Sutherland Welles tung oil varnish. Components received five coats of wiping varnish, with sanding in between, before the trusses were constructed [finishing nails and #10 stainless screws]. The trusses and top then received six more coats of medium lustre varnish. The top will get two more, then a final sanding with steel wool.

Not only did the varnish cost more than the wood, all this hand-finishing turns out to be an insane amount of time and effort. Even so, the incredibly uneven quality of the Ikea pine resists a fine finish. This top may be conceptually ideal, but a more practical solution may be required if we decide to use the table daily.

Previously:

Autoprogetazzione: The Making of an Enzo Mari dining room table

Ch. 1: Enzo Mari x Ikea Mashup

Ch. 2: Parts

Ch. 3: Decisions, Decisions, adapting Mari’s design for Ikea lumber

Ch. 4: Finish Fetish

Ch. 5: In Process (Rev.)

Ch. 6: Ikeaness

Autoprogettazione Updates From All Over

Sheesh, as if I wasn’t painfully aware of the nearly finished Enzo Mari x Ikea Mashup table sitting behind my sofa, I get this, from Peter Nencini, [above] which frankly just hurts:

A couple of weeks ago we reassembled 32 studio tables, originally built last year to Enzo Mari’s Autoprogettazione plans, published in 1974.

I’ll assume that they’re not putting twelve coats of hand-rubbed tung oil on theirs. At least I can hope my next 31 tables will go much more quickly.

Then there’s Wallpaper magazine swooping in with Autoprogettazione Revisted at the Architecture Association in London, where AA students and a few name designers show off their Mari-inspired hacks, and there’s even a lecture by Mari himself, which is alternately animated and tedious, and thanks to the on-the-fly translation, twice as long as it would normally be.

But even as I worry a bit about missing a trend–or worse, finding myself caught up in one–I’m reading the AA’s catalogue and instructions for the show–because yeah, I’d totally make Kueng-Caputo’s awesome lamp, wouldn’t you?–and I find this:

Mari was ultimately disappointed with the original response to Autoprogettazione, believing that ‘only a very few 1 or 2% understood the meaning of the experiment’…Enzo Mari hoped that the idea of Autoprogattazione would last into the future. Autoprogettazione Revisited reveals that it has done just that. Not all of the artist/designer responses in Autoprogettazione Revisited can be duplicated by the enthusiast, but they are inspirational and without a doubt follow the Mari principle that ‘by thinking with your own hands, by [making] our own thoughts you make them clearer.’

I’ve always understood Mari’s project to be a critique of the self-important distinction between the “artist/designer” and the “enthusiast.” In his lecture, Mari actually said that of the many thousands of requests for Autoprogettazione plans, only 1-2% of them were from design professionals. I can totally imagine the head of an architecture school gallery thinking that those two tiny, so-enlightened populations are the same, but I’m not at all sure Mari would agree with her. [thanks andy for the links]

Enzo Mari x Ikea Mashup, Being Mashed Up

ikea x Mari mashup being mashed up, originally uploaded by gregorg.

I realized I’d been putting off the actual assembly of my Enzo Mari table, daunted by the impending exactitude and fearful of the commitment of actually screwing all the pieces together.

Which seems to fly in the face of Mari’s original “just hammer it together” intentions for the autoprogettazione series.

I knew that without jigs and a flat surface and proper squaring equipment and such, I was invariably going to misdrill something, and then I’d be trying to redrill holes 1/8th of an inch to the left somewhere, and–

The joint that really made me nervous was the first one I’d have to do, drilling a 5/16″ hold through the center of all the side truss pieces [right about where the knot is in this photo] AND through the ends of the center truss, so that I could thread a carriage bolt through, and hold the entire table together properly. Forever.

Rather than risk screwing this up, I decided to piece each truss together with a steel bookend, and then hammer and wood glue enough joints to hold it. Then I’ll drill and screw the major joints after it’s together.

The carriage bolt and wingnut assembly method is a nod to the original autoprogettazione kits of precut wood, which were produced in 1973 by Simon International and sold briefly as the Metamobile Series.

I hadn’t thought of how much those simple wingnuts changed the nature of the autoprogettazione concept. They’re the difference between project and product.

The Metamobile kits weren’t just precut wood; they were also predrilled. And that required the construction of jigs, the use of some workshop- or factory-grade hardware, and probably even an assembly line, or at least some batch work. In other words, they were exactly what the autoprogettazione series was supposed to not be: mass produced.

Furniture sold as a kit of parts that comes ready to assemble, with just one tool, just follow the slightly baffling instruction diagrams exactly, and voila! Sound familiar? Enzo Mari beat me to an Ikea mashup by about 35 years.

Related: 14 June 2000, Lot 103: ENZO MARI, A PINE DINING TABLE

“designed 1973, manufactured by Simon International for the Metamobile Series, the square slatted top on open understructure secured by wing-nuts”, sold for £5,875. [christies.com]

Dec 15, 2006, Lot 2: ENZO MARI, AN EXTREMELY RARE “EFFE” TABLE

“Manufactured by Simon International, ca. 1974. from the Metamobile series…Acquired directly from Dino Gavina, c. 1975,” sold for $14,400 [sothebys.com]