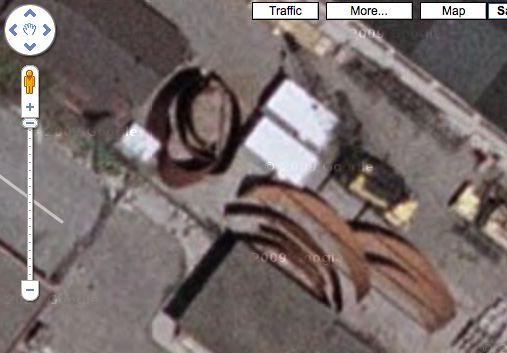

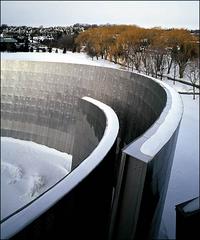

So last winter, after finding Jake Dobkin‘s, and Nathan Kensinger’s photos during my search for Richard Serra sculptures visible on Google Maps, I got a little fascinated with the massive Cor-Ten sculptures Richard Serra stores in a riverfront machine yard in Port Morris, the Bronx. Google Maps showed a Torqued Spiral as well as several long, arced steel pieces [above]. A presumably more recent image from Microsoft Live/Bing [below] only shows the spiral.

After talking to some friends at Gagosian and because there is a giant I-beam with “Bellamy” on it, I’d originally deduced that the Torqued Spiral was Bellamy one of Serra’s first spiral sculptures, which he’d shown in the fall of 2001.

But that turns out to be wrong. Writing about her visit to the stored Serra for the journal Afterall, Mary Walling Blackburn reports that it is not Bellamy after all. Bellamy is currently in England.

The “Bellamy” I-beam on-site [visible in Nathan’s photos], is apparently not a nametag or some such. Instead, they are used for stabilizing the curved pieces during transport and installation. They can be seen in use in Art21’s series of photos of Joe being installed at the Pulitzer Foundation in St. Louis.

So that begs the question: what Torqued Spiral is it, then? Inquiring minds might want to ask the artist next time they see him. I know I will.

Tag: richard serra

IRL: Art On Google Maps Smackdown

Paddy Johnson is taking the search for art on Google Maps to a place it’s never been before: In Real Life.

This Saturday, at Capricious Space in Brooklyn, Paddy is hosting a Google Maps artwork faceoff, a real-world, real-time challenge between two artists, James Turrell and Alice Aycock, to see which artist has more works visible to Google’s Eye In The Sky.

Check out details and get a headstart online at ArtFagCity. Meanwhile, I’ll be checking Capricious on Google StreetView regularly; I better not see you loafing around outside with the smokers.

In Real Life: James Turrell and Alice Aycock Face off on Google Maps! [artfagcity.com]

A Serra Named Bellamy

11/09 UPDATE: Or not. Writing about her visit to the stored Serra for the journal Afterall, Mary Walling Blackburn reports that it is not Bellamy after all. Bellamy is currently in England. There is, in fact, an I-beam on-site spray-painted “Bellamy,” [visible in Nathan’s photos below], but that is apparently not a nametag or some such. [In fact, the beams are used for stabilizing the pieces during transport. They can be seen in use in Art21’s series of installation photos for Joe at the Pulitzer Foundation in St. Louis.] So that begs the question: what Torqued Spiral is it, then? Inquiring minds might want to ask the artist next time they see him. I know I will.

The story of the Richard Serra sculptures stored along the Bronx waterfront is filling out, thanks to Nathan Kensinger, who went with Jake “The Dobster” Dobkin on their recent photoblogging expedition. A couple of highlights:

- Now we know which torqued spiral

ellipsethis is: Bellamy, named after Serra’s late friend and early dealer, Richard Bellamy. Bellamy founded the Green Gallery, though he only started showing Serra’s work in the late 1960’s after the gallery closed. Bellamy passed away in 1998, just as Serra had begun making his torqued ellipse and spiral sculptures. - Apparently, there’s a nameplate welded inside the sculpture. Can’t say I’ve noticed that before.

- Turns out we’d seen Bellamy before, at Gagosian in 2002 and the Venice Biennale in 2001. Considering we had to walk to the end of the Arsenale in the August heat, and then brave a horrible Vanessa Beecroft installation to see it, Nathan and Jake’s Port Morris fencehopping adventure doesn’t sound all that rough anymore.

- And the biggest piece of news from Nathan’s post, is that the Serras parked there are Serra’s. Which, given the storer’s acknowledged love of rust and industrial grit, and now knowing the personal resonance of the particular sculpture, seems obvious. Or maybe not so much.

Anyway, Nathan’s got much more to reveal, and some sweet photos to accompany it. Previously: Serra from the block

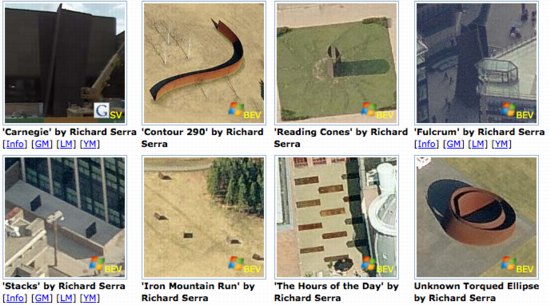

Richard Serra Sculptures On Google Maps

The whole thing about the only human construct you can see from space is the Great Wall of China will be amusing to people growing up in the Google Maps era, where you can’t hide anything from the satellite’s surveilling eye. It’s the geospatial equivalent of explaining TV before remotes and cable: it’ll just make you sound old.

So kudos to Richard Serra for being ahead of the curve [no pun intended] on making work that turns out to be well-suited for viewing from our new conveniently God-like vantage point.

I started to make a list with the Torqued Ellipse in front of Glenstone, Mitch Rales’ foundation in Potomac, and the suggestion from Guthrie of T.E.U.C.L.A., a torqued ellipse in the Murphy Sculpture Garden behind the Broad Art Center at UCLA, described at its installation in 2006 as “the first public work by sculptor Richard Serra installed in Southern California.”

And that reminded me that the Broads have had a Serra titled No Problem in their backyard for a while, which, thanks to Google Maps, is now public. Searching for that image led me to pmoore66’s collection of bird’s eye view Serras around the world at Virtual Globetrotting. If you count Robert Smithson’s Amarillo Ramp, which he helped complete after Serra Smithson’s death [!], pmoore66 has sighted 44 Serras around the world using either Google Maps, or Microsoft’s Bird’s Eye View, plus another four shots on Google Streetview. [Here are the search results on Virtual Globetrotting for “Richard Serra”, but that link looks a little unstable.]

With more than 1,700 entries so far, pmoore66 appears to be almost single-handedly pinning down the modernist canon for architecture and outdoor sculpture. This warrants some looking into. Stay tuned.

The more oblique angles of birds-eye-view seems to suit Serra’s sculptures better, and they remind me of a series of little desk tchotchke-sized versions of monumental sculptures called minuments that I saw in the ICA London bookshop a few years ago. As soon as I can figure out how to get Google to stop spellchecking for me, I’ll get the artist’s name.

Serra From The Block

Someone is storing his Richard Serra sculptures along the East River in the Bronx. As massive, vertiginously curved steel plates are wont to do, they tend to stand out, and so they get noticed or discovered periodically.

Jake Dobkin spotted them recently, and posted pictures of one of the Serra sculptures behind a barbecue and a busted fence. It’s a Torqued Ellipse [1] with the steel plates curled in a bit tighter than normal. Jan included a shot of the works on Google Maps, where they look nice sitting next to a collection of steel gas tanks. It appears that the other sculpture, a collection of six arced slabs in graduated sizes, is the disassembled–and ironically titled–Blindspot, presumably purchased from the artist’s 2003 show at Gagosian.

[Note to self and/or someone else: figure out how many Serras are visible on Google Maps? Former Dia chairman Leonard Riggio’s got one parked on his front lawn in Bridgehampton; Wave is installed at the Olympic Sculpture Park in Seattle; Joe, the first Torqued Ellipse, is in the courtyard at the Pulitzer Foundation; St Louis also has Mark Twain, a much earlier Serra downtown; I’m sure the list goes on.]

The first mention I can find of these ersatz Bronx Serras is from a 2005 NY Sun story about redeveloping public park space along the waterfront in Port Morris. The lot owner, Curtis Eispert, whose main business is storing cranes, quotes the sculptures’ owner: “He says, ‘I love the way it rusts in the salt air.'” [Hmm, it also says, “One piece, a wide band of curved and rusting iron that sold for $2 million, sat on a flatbed truck waiting delivery.” Could Serra be the “someone” storing his Serras in the city?]

Eispert also mentioned an “‘artists’ loft'” [the Sun’s scare quotes, btw] across the street, so “artists” must be aware of the Serras, too. Sure enough, In August 2006, a group of artists put on a show inside the Torqued Ellipse. Lan Tuazon and Marie Lorenz curated Invisible Graffiti Magnet Show, which consisted of magnetic works attached to the Serra for one Sunday morning. The exhibit persists, of course, as a press announcement and a flickr photoset. Above: works by the collective Dearraindrop and Matt Lorenz. Below: an LED throwie constellation by Virginia Poundstone.

Actually, ignore the “artists’ loft”; after reading up on Marie Lorenz’ fascinating Tide and Current Taxi project, I’m sure she spotted the Serras from the water, not the land.

Port Morris, scroll down for the Serra links [bluejake via x-ref]

Bomb the Serra! [triplediesel]

richardlovesmagnets’ photoset [flickr]

[1] 2/17 update: OK, now we know it’s a torqued spiral, not a torqued ellipse. photographer/filmmaker/Jake Dobkin accompanier Nathan Kensinger revealed that the sculpture is Bellamy, a spiral first shown in 2001.

A Favorite Kippenberger Made From A Favorite Richter

The Martin Kippenberger retrospective closed yesterday at MoCA, which means it’s just a few weeks away from opening at MoMA, which means I’ll finally be able to see one of my favorite-from-afar Kippenbergers in person.

The Happy Ending To Franz Kafka’s Amerika is always fun. And I love the Metro-Net subway stairs and vents for the trains that connect the world–the NY-style ventilation grate in the front lawn of LA’s Schindler House on Kings Rd still conflates those two cities for me.

“Haven’t you people ever heard of coasters??”

But the one I’ve been waiting to see is Modell Interconti. It’s a coffee table that Kippenberger made in 1987, and the top is made from a Gerhard Richter Grau painting. Kippenberger bought the painting as a Richter, then sold it as a Kippenberger, promptly destroying–or at least disappearing–a significant percentage of its market value.

Though I’m sure he didn’t take too big a hit. Richter’s grey paintings have never been as pricey as his less boring work: the blurred photo-based paintings, the gloppy aerial landscapes, the hard color grids, the squeegees. Which is part of why I like the grey paintings so much; they can be so successful at eliminating the extraneous elements and letting you focus purely on the paint, the surface, the object. And the range is anything but boring. Those giant grey glass paintings at Dia:Beacon create a space as seductive and perceptually disorienting as any Serra.

Ten years after Kippenberger made Modell Interconti, you could get a slightly smaller Richter grey painting at the Armory Show for around $10,000. Which was probably the price of a major Kippenberger by then, too. So within a decade, Kippenberger had caught up with Richter’s market. And now a major Kippenberger–like, say, Modell Interconti–is surely worth more than a small, demure Richter. At least it was pre-meltdown.

Modell Interconti, 1987, collection Gaby and WIlhelm Schürmann [image: swo.de, link broken (2016)]

The MoCA photo used by the LA Times is probably better. [latimes]

2016 update: Chin-Chin Yap’s case study of the moral rights associated with Modell Interconti, from July 2009 [artasiapacific]

If I Were A Sculptor, But Then Again…

Yes, I do have a ton of other things I should be doing, but I can’t seem to get Project Echo out of my head. I really want to see this, 100+ foot spherical satellite balloon, “the most beautiful object ever to be put into space,” exhibited on earth. But where?

When MoMA was designing its new building, a lot of emphasis was placed on the contemporary artistic parameters that informed the structure. The gallery ceiling heights, the open expanses, the floorplate’s loadbearing capacity, even the elevators, everything was designed to accommodate the massive scale of the important art of our time: Richard Serra’s massive cor-ten steel sculptures.

And they did, beautifully, until just a few days ago.

But is there anything more anti-Serra, though, than a balloon? Made of Mylar, and weighing a mere 100 pounds? And yet at 100 feet in diameter, a balloon of such scale and volume, of such spatially overwhelming presence, it dwarfs almost every sculpture Serra has ever made?

The original Echo I was launched into space, but it was explicitly designed to be seen from earth. It was an exhibition on a global scale, seen by tens, maybe hundreds, of millions of people over eight years. People from the Boy Scouts to the king of Afghanistan organized watching parties. Conductors stopped mid-outdoor concert when Echo passed overhead.

L: Hayden Planetarium = 87-ft diam. R: Pantheon = 142-ft. HEY!

What would an Echo satellite do to the art space it would be exhibited in? Are there even museums or galleries who could handle it? Or is the physical plant of the art world still organizing around the suddenly smallish-feeling sculptures of, say, Richard Serra?

Echo satelloons were first seen–or shown, isn’t that why there’s a giant NASA banner draped across it?–in a 177-foot high Air Force blimp hangar in North Carolina. There are plenty of non-art spaces where an Echo could be exhibited, but that misses the whole point.

What art spaces in the world are able to physically accommodate an 10-story high Echo? A gallery or museum would need unencumbered, enclosed exhibition space of at least 120 feet in every dimension:

Suddenly all these atriums and rotundas you think are just grossly oversized turn out to be too small. I guess the art world’s space limitations will be the constraining parameter for my Project Echo exhibition.

Maybe the only thing to do is to show it in a non-art-programmed space after all. Grand Central Station’s concourse is 160 feet wide and 125 feet high in the center. And as a bonus, a US Army Redstone rocket was exhibited there in mid-1957 [via wikipedia]. It was lowered through a hole cut in the constellation-decorated ceiling.

And then there’s the Pantheon, which is built on a 142-foot diameter sphere. As readers of Copernicus, Walter Murch, and BLDGBLOG will know, the Pantheon “may have had secretly encoded within it the idea that the Sun was the center of the universe; and that this ancient, wordless wisdom helped to revolutionize our view of the cosmos.” What better venue for displaying a satellite which indirectly helped revolutionize our view of the origins of the cosmos? And not that it’s necessary, but it even already has a hole in the roof.

Unless I do it outside, Maybe in the Piazza San Marco, where Gregor Schneider’s 46-foot, black, shrouded Venice Cube sculpture was supposed to be installed during the 2005 Biennale. But would a recreation of a relic of American military and media propaganda be any more welcome in Venice than a replica of the Kab’aa? [So I just follow Schneider and install it two years later in the plaza in front of the Hamburg Kunsthalle? I’ll get right on that.]

Or maybe the answer’s right in front of me, and I just don’t want to admit it. Here’s what I wrote last winter about the Sky Walkers parade staged last December by Friends With You [and sponsored by Scion!]

It’s what I’ve always said Art Basel Miami Beach needed more of: blimps.

The only art world venue which can accommodate a 100-foot satelloon is an art fair.

Also of interest: A 1960 Bell Labs film, The Big Bounce, produced by Jerry Fairbanks, tells a very Bell-centric version of the Project Echo story. That horn antenna is something, though. [archive.org, via Lisa Parks’ proposal to integrate satellites into the traditional media studies practice]

Huge Props

So if you’re going to see the Richard Serra exhibition at MoMA–and you should, it’s really quite spectacular–you should see it when the museum is closed, because then you have the whole place to yourself.

A friend John and I went last Tuesday morning, and we started on the sixth floor. By the second room, it was obvious that the experience of the show was really incredible. Serra’s an artist who, by design, almost prevents you from seeing multiple examples of his work; they’re site-specific–not just permanently installed in or made for, but actually about the site and the experience of being in it. By the second Serra, then, you realize you’re in rarified territory. And the first three room-filling works you encounter at the entrance of the sixth floor space really makes this clear.

The silence was shortlived; there was a crowd of middle school students sitting on the floor in the next gallery, which was crowded with very early works. I wanted to go grab each of these kids by the shoulders and shake him, saying “Do you know where you are? Remember this!” But I figured they’d figure it out by the time they got downstairs.

Was it Peter Schejldahl who mentioned how sad and domesticated the corral of prop pieces looked? I’m afraid he was right. I’m also afraid I couldn’t imagine any other way MoMA, with its constant crowds, could show the precarious work. These delicate, human-scale pieces are not the Serras around which the new building was designed, and it shows. [The hands-down best prop piece I’ve ever seen, by the way, was in the office of a dealer on 24th street. It was a square metal sheet held up by a roll that sat on the floor like a lead umbrella. The fleshy soft surface was in seductively pristine condition, too, a testament to a life in careful storage, I guess.]

The massive second floor galleries, where Serra’s early lead and timber scatter piece seemed so lost in front of the Twombly when the museum reopened, now seemed complete. The torqued ellipses and ribbons of Serra’s late/current period are, as John aptly pointed out, our real Peace Dividend. They’re made possible–and made–by advances in Military Industrial design software and manufacturing. Prowling around NASA in the past, I’ve seen utterly utilitarian instruments, objects, and components whose stunning aesthetics would drive a hundred MFA’s into the web design business.

Serra seems like one of the few artists to make a sustained, legitimate attempt at actually engaging the means of production of the Cold War. And when you consider the price tag of the new MoMA as a purpose-built context machine for these works compared to, say, the Pentagon’s weekly expenditure in Iraq, the ROI is off the charts.

All that said, my favorite piece in the show was not, in fact, one of the sexy, transporting, transformative curved mazes on two, but a much earlier piece on six. [It could be, but it’s not To Lift, the 1967 piece made of sheet rubber, which is easily the most elegant.] Circuit II, [1972-86] is a giant prop piece which has been in MoMA’s collection for a while. Four straight steel plates are wedged into the corners of a room, creating an unsettling, compressed void where they would intersect. Circuit II was installed when I first moved to New York; it was in the Philip Johnson annex gallery known as the basketball court, which, at the time, had been the largest space in the Modern. The simplicity of the execution and the visceral spatial experience left a real impression on my fragile little just-graduated college mind. It was a kind of non-academic awe that my skeptical art history professor’s cursory lessons on contemporary art had not prepared me for.

I’d like to say I felt that sensation again, but to be honest, the new sixth floor galleries are so high, and the beautiful skylight overhead was so open, Serra’s once-overwhelming plates felt a bit quaint and conceptual, the idea of awe instead of awe itself. Or maybe it’s just me. Maybe it’s not so much the work, but my own spatial nostalgia, the kinaesthetic memory of it, that I’m loving so much, that thrill of paradigm-shifting discovery when you’re young and stupid–and your paradigms are due for several hefty shifts. Maybe Richard Serra’s works are not just shapers of space; after you’ve encountered them once, they become manipulators of time, too.

Richard Serra Sculpture: Forty Years [moma.org, thanks alex]

The Ingredients In The MoMA Artists’ Cookbook

Seriously, where do they find this stuff? In the 25th issue of the inimitable Cabinet Magazine, Jeffrey Kastner has a few tasty excerpts from The Museum of Modern Art Artists’ Cookbook, by Madeleine Conway and Nancy Kirk, published in 1977.

The day I got my magazine, I quickly ordered one of the few copies of the cookbook I found online [Abebooks, the Museum edition is much more expensive, but the spiral bound trade edition seems easier to cook from.]

Definitely read Kastner’s piece for some great quotes about food and meals from various artists, including some who are still household names, and others who are decidedly not. The book is as quaintly provincial as you’d expect, a fascinating time capsule of circa 1970’s culinary sophistication.

Will Barnett enthuses over “a small shop on Spring Street where they make the best bread in the world.” Louise Bourgeouis likes to entertain after the galleries close and before the jazz clubs open, serving foods “that are largely unfamiliar to most Americans but are a delicacy in her native France,” such as endive and fennel. Helen Frankenthaler worries where in the city to get red lettuce from California. Alex and Ada Katz have a thing for fresh chanterelles, “the essence of conspicuous consumption.” So many things that have since been thoroughly absorbed into the mainstream of American food, whether by expansions of taste or distribution.

The other thing that caught my eye is the mix and age of the artists included in the book. It’s unrealistic to judge a museum’s curatorial program by the cookbooks it publishes. If it the list of recipe contributors is indicative of anything, it’s probably the social networks of the authors and who they could get to respond to their solicitation.

Still as I scan the list of recipe contributors, who the subtitle bills as “thirty contemporary painters and sculptors,” I can’t help but think of The Modern’s ongoing relationship with the contemporary art world, which has come under increased criticism the last few years.

There’s a definite New York-centricity to the list. And the youngest artist included, Red Grooms, was 40 years old at the time, born in 1937. [The next youngest is Richard Estes (1936).] Were younger artists in their 30’s–like Nauman, Serra, Marden, Elizabeth Murray, for example–not on MoMA’s speed dial at the time? What about artists not included, Pop artists like Rauschenberg and Johns, or Minimalists Flavin, Judd, or Morris?

Between the middle age and the omissions, I can’t help but wonder if MoMA’s complicated, incomplete, and variably unsatisfactory interactions with the art of the moment isn’t a new phenomenon brought on, supposedly, by corporatization, but something persistent, recurring, endemic? I’ve read interview transcripts of Robert Smithson and Allan Kaprow inveighing against Bill Paley and his CBS friends at the museum.

But isn’t rebelling against authority what the kids in any era do? Just as longing for the good old days is a pasttime for the aging/aged? These kinds of cultural criticisms resist self-awareness. But by comparing snapshots of the past to the present, we can see how and where our cultural constructs have changed. At least 12 of the artists in MoMA’s 1977 cookbook–Indiana, Grooms–have receded from the current art world dialogue; the names of some, like Raphael Soyer, Audrey Flack or Ernest Trova, would draw blank stares from most of the art-engaging world today. Meanwhile, endive and arugula are available at McDonald’s.

Some Iceland Photos: Richard Serra

I went to Iceland a couple of weeks ago, and I just put some photos up on flickr from the trip.

This one is of Afangar, a sculpture/installation by Richard Serra. The tops of these squared off basalt columns are level, but one column is 4m high, while the other is 3m. The distance between them, then, is determined by the slope of the land.

Serra placed nine pairs of colums around the periphery of one half of Videy, this island in the Reykjavik harbor, and some of them are quite close together; others, like these, are far apart.

The main feature as you walk, though, is bird droppings. When I first visited Videy in 1994, it was November, and except for a couple of Icelandic horses, I was alone on the island. This time, though, the place was teeming with sea birds, and the faint trail through the grass was chock full of tern turd. When you’d inadvertently get too close to an invisible nest, the birds would get really agitated. One nest was right next to the trail, and we didn’t see it until the mother flew out from underfoot and startled us. A lot of the Serra columns on the leeward side of the island are topped with a crown of guano, but the windward side is pretty clear.

It surprised us to see Olafur Eliasson’s Blind Pavilion from the 2004 Venice Biennale perched on top of the hill above the ferry dock, though. Apparently, they installed it there in early 2005 as part of his show at the National Museum. It looks like a gun turret up on there, though.

Torqued Eclipse*

“Ms. Luce gave the design team at Nissan a steel wall to hide works in progress.”

And then Mr Serra gave Ms. Luce and the design team at Nissan a good legal shellacking.

Architecture and Carchitecture [nyt]

* I KNOW, it’s Mitsubishi. Come up with a good hed using a Nissan model, and I’ll change it.]

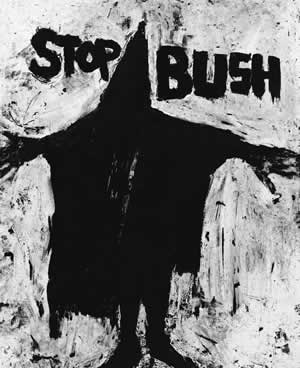

The Mellowing of Richard Serra

[via MAN] What’s shocking about Richard Serra’s poster for pleasevote.com–a thick paintstick silhouette of the hooded Abu Ghraib prisoner–isn’t his use of text or figurative representation, both completely absent from the rest of his work (with possibly one 1960’s exception).

And it’s not his political activity. He’s always been an active liberal, and his art challenges both easy commodification and conservative notions of authority. And who can forget his legal battle with the GSA and anti-NEA zealots like Jesse Helms which culminated in the destruction in 1989 of his sculpture Tilted Arc (besides pretty much everyone, that is)?

No, what shocked me was his positively statesman-like restraint, which stands in contrast to the horrible image in his drawing and to current levels of Administration discourse. With STOP BUSH, Serra–who’s well known for his angry temper–let’s George off easy.

In 1990, he made an etching as a fundraiser for North Carolina Senate candidate Harvey Gantt, who lost after his opponent ran some race-baiting ads that have become recognized dirty tricks classics. The title of that piece (sorry, mom) was Fuck Helms.

Praise for Artforum.com and blurbs re Richard Serra

Let me offer unqualified praise for the editorial acuity of Artforum’s links recommendations.

Two quotes from Calvin Tomkins’ good Richard Serra article in the New Yorker:

According to Richard Serra:

Abstraction gives you something different (from figuration). It puts the spectator in a different relationship to his emotions. I think abstraction has been able to deliver an aspect of human experience that figuration has not–and it’s still in its infancy. Abstract art has been going on for a century, which is nothing.

About Richard Serra’s usually high degree of professionalism and realistic approach to commission negotiations (from his longtime European dealer, Alexander von Berswordt): When he calls someone a motherf***er, that doesn’t help, of course. But he rarely does that without a reason.