The stories of Jasper Johns’ Flag is almost as famous as the artwork itself. In 1957, Leo Castelli had come for a studio visit with Robert Rauschenberg, only to find Jasper Johns’ work there, and offer the younger, unknown artist a solo show on the spot. That 1958 show, Johns’ first, ended up on the cover of Art News. Alfred Barr bought three works out of it for MoMA. When more conservative trustees balked at the possibility that the till-then-unknown artist might have unpatriotic intentions, Barr leaned on Philip Johnson to buy a fourth, Flag.

And of course, there’s the story of how Johns made it, which MoMA lays out succinctly:

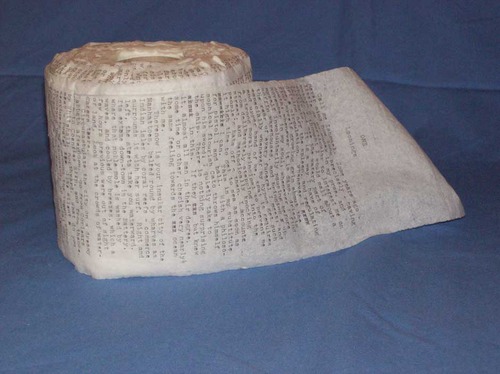

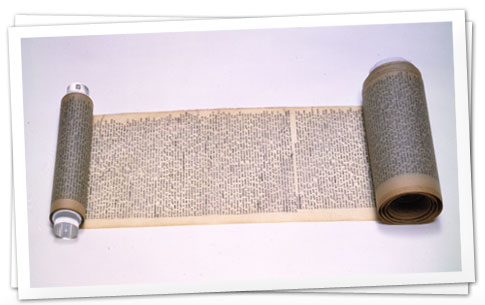

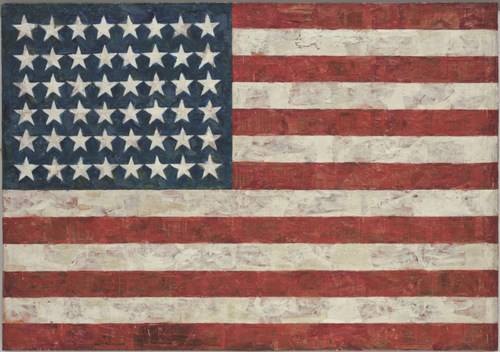

“One night I dreamed that I painted a large American flag,” Johns has said of this work, “and the next morning I got up and I went out and bought the materials to begin it.” Those materials included three canvases that he mounted on plywood, strips of newspaper, and encaustic paint–a mixture of pigment and molten wax that has formed a surface of lumps and smears. The newspaper scraps visible beneath the stripes and forty-eight stars lend this icon historical specificity. The American flag is something “the mind already knows,” Johns has said, but its execution complicates the representation and invites close inspection. A critic of the time encapsulated this painting’s ambivalence, asking, “Is this a flag or a painting?”

But what’s not exactly so clear is when Johns actually made Flag. It became so famous and influential so quickly, and its story is so fantastic–a dream! a flag! a magazine cover! MoMA!–that the pre-1958 history gets compressed into a largely uninvestigated corner.

MoMA’s listing officially, and oddly, notes the date for Flag as “1954-55 (dated on reverse 1954).” So 1954-55. But perhaps 1954. Not an idle difference, I think. But there’s more.

From an awesome footnote in Michael Crichton’s awesome 1977 Whitney catalogue:

Occasionally his working methods cause curatorial problems. One long-standing question concerns the date of his first Flag painting, originally purchased by Philip Johnson in 1958, and now in the collection fo the Museum of Modern Art. The painting was dated 1954, but Johns argued that it was done in 1955. Recently someone noticed that the collage included newsprint from 1956, and the museum wanted to change the date accordingly. Johns stated that the picture was damaged in his studio in 1956, and that he repaired it that year, but that the painting was still properly dated 1955. He also points out that certain early works include collage elements that are old–much older than the paintings themselves–thus obviating entirely such direct methods of dating. [p. 65]

So this painting, “his first Flag painting,” has 1954 written on the back. The artist argues for 1955. Some collage material visibly dates from 1956. And then the artist warns against attempting to date a work by the date of the collage elements. But isn’t the issue here not that it could appear to be earlier than it is, but that it’s actually later than the artist claimed? Twice?

I would think that contemporary analytical tools exist that can test whether Flag was repaired as Johns claimed. Or maybe close looking is sufficient. Crichton set up this curatorial dating problem with one of my favorite quotes from the catalogue:

A note of caution: Often John’s [sic] “laborious efforts” to cover actually draw attention to what has happened. One may speculate that the layered meanings in a Johns work have their analogue in the layers of paint and wax that sometimes conceal, sometimes reveal, what lies beneath. That is one way to look at it. Another way is to recognize that he is a painter whose interest in process leads him to reveal the process–as an action over time–to the viewer. That is, a series of events and decisions led to the final picture; Johns often seems as interested in the sequence of steps as he is in the final result–at least, he often tries to show “what happened” along the way. It may be exaggerated to say that a Johns painting contains its own biography, but that kind of idea is present in many pictures.

Maybe it’s the artwork’s instant iconic status, or maybe it’s the power of the alluringly iconic image it depicts, but lately, it feels like I’ve begun taking closer looks at Flag for the first time. And it’s pretty surprising.

One thing’s for certain, though: Flag is not Johns’ first flag painting. [cont’d]

Jasper Johns, Flag, “1954-55 (dated on reverse 1954)” [moma.org]

Fred Orton’s 1996 book Figuring Jasper Johns is one of the few in-depth analyses I’ve found of Flag. [amazon]