There are so many fascinating things about the Gene Davis Giveaway, I almost don’t know where to start. And I’m embarrassed to not have known about it sooner. Gene Davis Giveaway, or Give Away, or as it was called at the time by its creators, The Event, was an amazing art project, part Happening, part Conceptual Art, part ur-Post-Modernist appropriationist market critique, and–yes–part Relational Aesthetics mayhem. And it happened in Washington, DC, in 1969.

The story, as it was fed to Washington Post critic Paul Richards, is that in the spring of 1969, DC sculptor Ed McGowin and art critic/artist Douglas Davis were at a party, trying to figure out how to declare the end of the once-edgy, now “Establishment”-friendly Washington Color School movement. Douglas wanted to “gather [all] the color paintings and destroy them,” and McGowin said no, “let’s give them all away.”

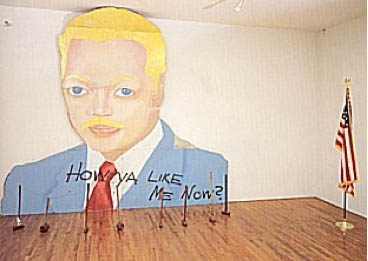

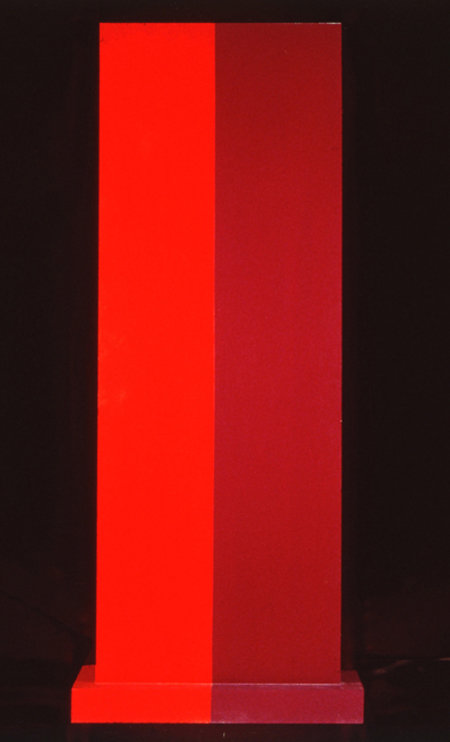

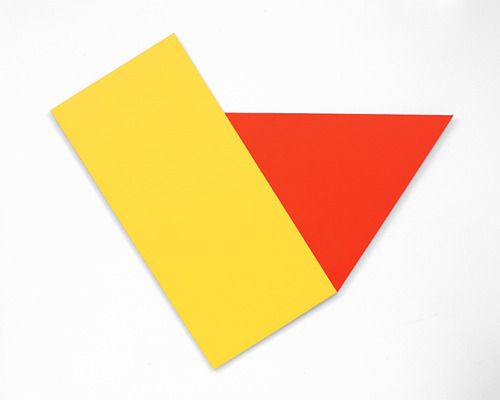

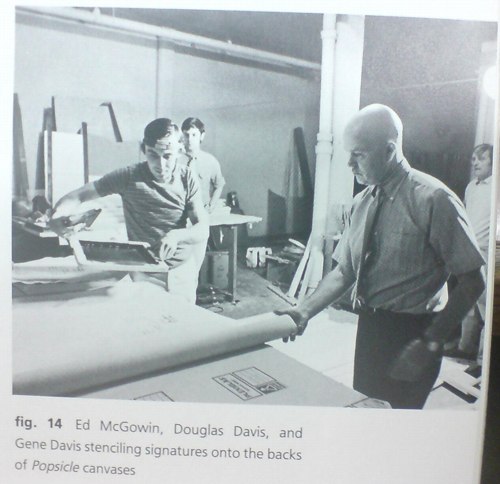

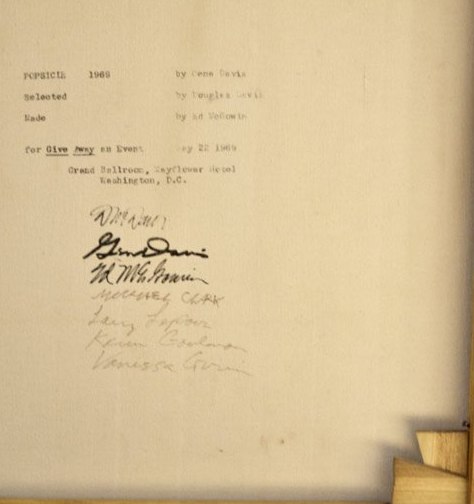

So they approached Gene Davis, who agreed to let McGowin and Davis make 50 replicas of Popsicle, one of his trademark stripe paintings. Davis mixed and supplied the paint, while McGowin and some art students from the Corcoran–including Clark Fox–produced the 6×6-ft paintings. When it was all done, Gene came to silkscreen the three creators’ signatures on the back of each canvas. Sometimes the fabricators signed the works, too.

McGowin and Gene Davis screening Giveaway signatures with Douglas Davis looking on, from Douglas Davis’s The Giveaway Box, via Gene Davis: A Memorial Exhibition, 1987

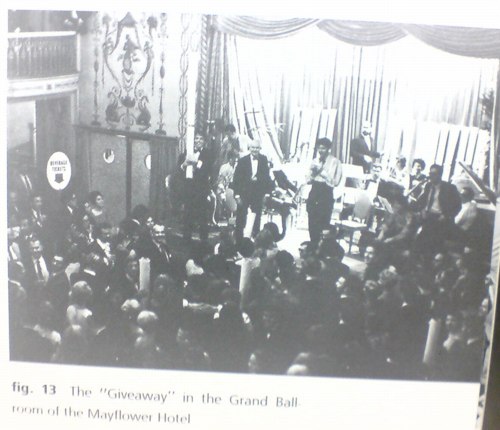

Meanwhile, Douglas invited 500 local swells to a black-tie party in the ballroom of the Mayflower Hotel, where the 50 “Gene Davis Paintings” would be given away, free, to lucky attendees whose names were pulled from a large bowl. [Actually, I think it was 40 paintings, because 10 had been pre-sold to folks who underwrote the production of “The Event.” I’d bet they were exchanged for around $1,000, an attractive discount from the $3,000 price of an “original” Davis painting at the time.]

And that’s how the Gene Davis Giveaway was positioned at the time, and apparently, for long afterward: Gene Davis paintings by any other name that still looked as sweet. At 0% of the price.

In his uncannily prescient and expansive preview of Gene Davis Giveaway in the Post, Richards likens the project’s collaborative “assembly line production” to “a different sort of event that not so long ago celebrated the dominance of another kind of painting.” Which, obviously, I must quote at length:

That earlier event was performed on a Willem de Kooning drawing by Robert Rauschenberg, a painter then unknown [sic]. The drawing had been made freely, almost automatically, in the abstract manner with soft pencil on fine rag paper. Working freely, almost automatically, in the abstract expressionist manner, Rauschenberg erased it.

Traces of pencil marks remained so that the handwritings of both artists were visible when their work was shown as “Erased de Kooning by Robert Rauschenberg.”

Rauschenberg’s gesture marked a point in the history of art. His erasing did not destroy–but underlined–the premise of the artwork it altered. Freehand erasing is to freehand drawing as mass production is to the tedious production of an “original” Gene Davis stripe.

That’s one way of looking at it. There are others. Some see the Giveaway as a publicity gimmick and others see it as a way to get something nice for nothing and still others regard it as a joke. Douglas Davis feels the Giveaway–with its color, its lottery, its glamor, its suspense–is itself a special work of art.

Wow. Exactly! Except that I think Richards’ actual take was one or more of those unnamed “others,” and that Davis & McGowin fed him the rest. When Douglas looked back on Gene Davis Giveaway in 1987 in a catalogue essay for the recently deceased painters’ memorial exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum that re-examined the project in light of postmodernism’s challenge to originality and authorship, Richards poo-poohed it all as “self-congratulatory hyperbole.”

Which you’d expect if Richards thought the Event was a “publicity gimmick” or a “joke,” but not if it were “a special work of art” which just so happened to align with, if not prefigure, the contemporary art world’s next two decades of conceptual and theoretical developments.

By Douglas Davis’s 1987 account, though, there’s no question that he and his collaborators “were in the midst of artmaking,” and that the art was “The Event” itself:

What I remember most about that evening is the roar. The crowd was enormous, virtually filling the gigantic ballroom [above]…The atmosphere approached that of a ritual, yes, but the ritual of Wall Street or striptease. Very early, the chanting began: “Give it away, give it away.” When we finally drew the names of the winners out of a large silver bowl, the yelps and screams of the victors, and the groans of the losers, were earsplitting. I began to feel ashamed of myself. Barbara Gold of the Baltimore Sun was the only critic who sensed the conceptual edge in “Giveaway.” She claimed that the patrons calmed down toward the end, stunned by their own vulgarity, by the shock of recognizing “how totally monetary value could get in the way of the aesthetic pleasure.” “A vague air of sheepishness became pervasive,” she wrote. I hope her reportage is more accurate than my memory. I recall nothing but loud, overbearing greed to the last. Photographs reveal the winners waving their rolled Popsicles in the air as they left the Mayflower, dancing above a sea of black-tied oglers. At least for the moment, free art, having found its owners, returned to the realm of the precious. No, Walter Benjamin, the aura of Popsicle glowed that night in fifty different directions.

Alright, maybe that is a little hyperbolic.

In any case, I think it’s clear that under the Erased de Kooning analogy, Gene Davis Giveaway is really a work by Douglas Davis and Ed McGowin. But that poses the uncomfortable question, what if you erase a de Kooning, but you don’t become Robert Rauschenberg? For all his DC Happenings and on-point conceptualizing, Douglas Davis is less well known for making art than for his 1970s tenure as the art critic at Newsweek, and for organizing the Open Circuits symposium that brought video art to MoMA in 1974.

And while Gene Davis’s market is pretty sleepy, it’s still more established today than either Douglas’s or McGowin’s. And so it is that most of the Popsicles in public are optimistically/delusionally presented and traded as Gene Davis. Because even in 1987, Douglas didn’t realize his project would also prefigure the eventual acceptance of editioned originals and outsourced painting.

So while you can put on a happy conceptual face and say the piece is still working, on another level, it’s gotta hurt when, as recently as 2010, Douglas Davis’s own copy of Popsicle is being sold–along with his Giveaway Box, the trove of ephemera, documentation, and related materials he’d assiduously collected as part of Gene Davis Giveaway–as a Gene Davis. That’s like the A/P right there, the ur-After Popsicle, and it still only makes $11,000.

[2018 update: in 2016 Clark Fox wrote about his experience making all 50 “Gene Davis” paintings in nine days.]