For he that hath eyes and was paying attention last year, The Selby let him see. For the rest of us, the show at Sperone Westwater is the first time to see Tom Sachs’ awesome Donald Judd furniture hacked together from particleboard scraps from the IKEA AS-IS department.

Hacked is, of course, not the right word. The chairs are constructed with Sachs’ characteristic attention to craft and process: they show every drip of resin, every bubble and lump in the fiberglass joinery.

For me, the best part is that the pieces date from 2009. And in November 2009, the first issue of Bricolage Magazine, Tom’s zine, included a feature titled, “Ikea vs Judd.” Because as awesome as they are on their own, they’re even better for not being Enzo Mari furniture.

Tom Sachs: WORKS, Nov 4 – Dec 17, 2011 [speronewestwater.com]

Tom Sachs site [tomsachs.org]

6.14.10 Tom Sachs in his studio [theselby]

Tom Sachs studio film, by The Selby [vimeo]

Previously, resonant, not related: Enzo Mari X Ikea mashup

howtospendit.com +rirkrit

Thanks to Awl for reminding me that not everyone is not talking about Rirkrit Tiravanija’s sexy, blingy objects. I’d found this last week, but it was crashing my browser, and it may do the same to yours, probably because it’s designed for folks who trade up their computers with the same frequency Steve Jobs traded his AMG SL65.

The Financial Times’ luxury lifestyle magazine supplement How To Spend It loves Rirkrit’s work.

In “Art Works: Spectacular Sculptures – with a purpose,” Helen Chislet delivers servicey with a smile by revealing the “spectacular and tremendous fun” that can result “when artists are asked to design functional outdoor objects.” Objects like Rirkrit’s “ping-pong table of flawless mirror-polished stainless steel in an edition of ten–a piece of perfectly executed workmanship that carries a price tag of $55,000.” [no correction to my original price mention; if you want to pay 10% more that’s your business -ed.] Objects which are still likely to appeal to the FT’s ideal UK-centered international demo, typified by one garden folly maker’s client base as “City workers relocating to the country, but now includes European royalty and “extraordinary people.”

And the Palm Pavilion at Inhotim gets a starring role in “Artward Bound,” Pernilla Holmes’s round-up of far-flung private art parks, which, I love this:

“So much contemporary art is commodified,” says [Doug] Aitken. “A place such as Inhotim works against that. It empowers the artist rather than curating the artist. It’s a phenomenal template for a modern museum.” Unlimited by budget constraints, bureaucracy, timescales and space, such privately owned modern museums are popping up in spectacular, middle-of-dowhere locations around the globe as moneyed art collectros turn the traditional museum model on its head. Each is as unique as the personality of the person who dreamt it up.

Aitken really does have his finger on the pulse of these things.

previously: relational aesthetics for the rich

the gala-as-art movement [vimeo]

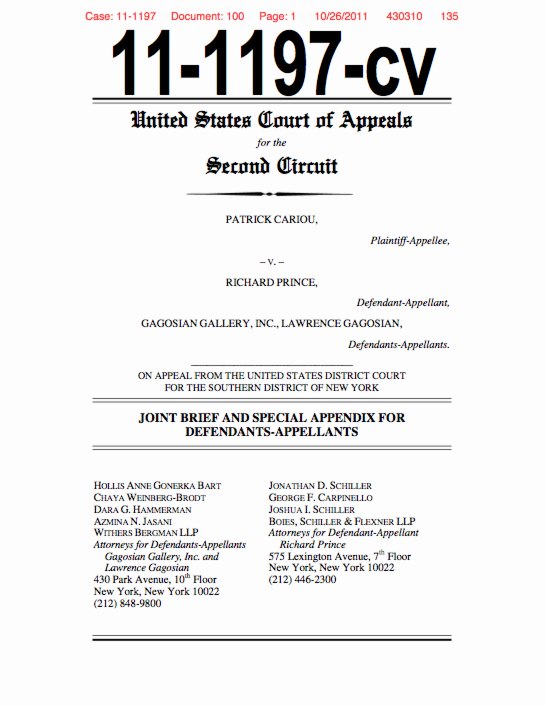

Richard Prince And Friends

I’ve tweeted on this a bit already, but it’s really worth repeating: Richard Prince’s appeal of the Patrick Cariou copyright infringement decision is a really great read. The brief was filed last week, and I finally got around to reading on Halloween night. I find it makes a very clear and persuasive argument for throwing out Judge Batts’ sweeping ruling, and it’s a nice, not too esoteric discussion of appropriation and fair use as well.

Basically, Prince, his new lawyers, and Larry Gagosian argue that Judge Batts wrongly applied the prevailing legal standards for fair use, especially the most recent, relevant case which had been before the same court, Blanch v. Koons.

I think I’ve written before that Prince’s work, and his first-round defense, relied very heavily on Koons’s winning argument that an artist’s transformations of size, scale, material, and context were sufficient for fair use. But their briefs almost never cited Blanch and did not make that transformative use argument clearly or well. That has changed.

Prince’s lawyers also argue that Batts overreached and erred by finding all 30 of Prince’s Canal Zone works to be infringing, regardless of what, how, or how much of Cariou’s imagery they contained. And that it’s wrong to force Prince to hand over all the artworks to Cariou when the settled precedent of monetary compensation exists.

I think that, at the very least, the court will find that each painting must be evaluated, and that the court will have to decide Prince’s transformative efforts. While I would love to publish such a document, because it would just be the best kind of worlds-colliding art criticism around, I suspect a check will be cut before the judges take out their rulers.

I could rattle on about this all day, but why not just read it yourself? Here is a copy of Prince’s filing, which I’ll host on my Dropbox own site for a while. The 135-page ruling has a lot of very nice, full color illustrations and clocks in at around 7mb.

[OBVIOUS DISCLOSURE ABOUT GREG.ORG AND THE CREATIVE CAPITAL | WARHOL FOUNDATION ARTS WRITERS PROGRAM, WHICH IS COMPLETELY UNRELATED TO THE FOLLOWING PARAGRAPH, HERE.]

And in even more interesting news, Joy Garnett just gave me a heads up that the Warhol Foundation has actually filed an amicus brief in Cariou v. Prince, warning the courts that if Judge Batts’ ruling were to stand, it would put works by other artists in jeopardy, and would cause “such uncertainty in the field as to cause a chilling effect on the creation of new works.” I expect I’ll come back to this after I read it all, but the Foundation’s brief defends Prince’s work as part of a broad, artistic history of appropriation, quoting, and collage. Should be interesting. The Foundation’s 57-pg brief [pdf] is linked directly here.

Previously: the five most ridiculous things about the Richard Prince copyright decision

The Richard Prince decision? You’re soaking in it!

Richard Prince’s Spiritual America

Size Matters?

“THE WITNESS: This could be a cool book.”

“The Movie is called ‘Eden Rock'”

The View Of Punishment Park From Zuccotti Park

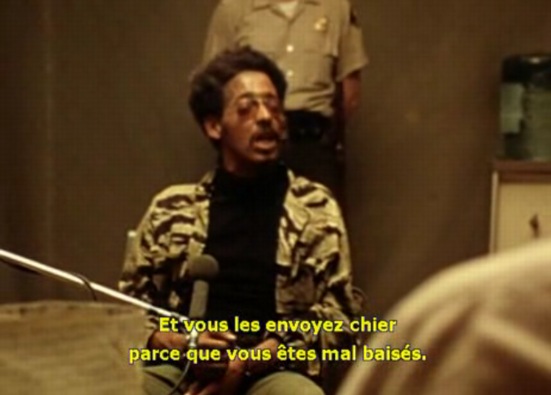

Punishment Park? How did I not know about Peter Watkins’ incendiary 1971, anti-war, anti-fascist, faux-news documentary? I mean, it was the movie Rirkrit chose to broadcast on his unlicensed TV station in the Guggenheim. I sat in Anthology’s rickety seats for the entire 5+ hours of The Commune (Paris, 1871). Is it one of those things that just looks so completely, unrecognizably different in the light of Occupy Wall Street, that–no.

When Punishment Park was finally released on DVD in 2005, it was the peak of a globally unpopular war, which was tainted by torture, unlawful detainment and military tribunals, violations of basic constitutional and human rights, and polarized rhetoric within American culture. So no, I don’t think I registered what Watkins had done.

Which, holy smokes. Here’s how Holland Cotter describes Punishment Park in his 2005 review of Rirkrit’s show:

it is a docudrama about the brutal silencing of antiwar protesters during the Vietnam period. Many of the actors were amateurs. The people cast as activists were, in fact, real-life activists; the police were played by former police officers.

Their lack of theatrical training gives the film a curious tension, making it seem both authentically documentary and stagy. It feels something like that era’s political street theater, which was cropping up all over the United States and Europe at a moment when anger and paranoia were at flood tide. This aesthetic certainly suits the low-tech character of the broadcast facilities, which are pretty rudimentary.

Shooting in an army tent and the Mojave Desert, a British news crew follows two groups of activists/protestors as they are run through a sham tribunal and are given the choice between excessive federal prison sentences and an impossibly brutal three-day race across a vast desert reservation, aka “Punishment Park,” where they are hunted down by National Guardsmen training for the next Kent State.

It’s like Predator and The Tenth Victim gave birth to the sequel of Zabriskie Point, starring the Chicago Seven. It is not pretty.

Punishment Park may not be a great movie, but it is definitely a fascinating one, one which is difficult to watch, and apparently difficult to like. I think that’s by design, though; it seems calculated to antagonize and/or enrage basically anyone with a political opinion and a stake in the outcome of the American experiment. It deserved a little more credit than it got, though, and certainly better consideration than Vincent Canby was capable of:

Because all literature, including futuristic nonsense like this, represents someone’s wish-fulfilling dream, I can’t help but suspect that Watkins’s cautionary fable is really a wildly sincere desire to find his own ultimate punishment.

Yow.

The freaky thing, I guess, is the way Punishment Park manages to both over- and under-predict the cultural rifts and abuses of power in American politicized culture over the intervening 40 years. I think had I seen Punishment Park in 2005, I would have distanced it as a historic, histrionic artifact. But given the last few years/months/weeks, I can’t help but see parallels and hear echoes between the film, its time, and today.

The other, less uncomfortable thing–I mentioned Zabriskie Point for a reason–is how Punishment Park alters the context of the 60s and 70s for me. I can’t help but see the counterculture and the desert, the military and the desert, war and the desert, art and filmmakers in the desert, quite differently now.

The New Yorker Films DVD release of Punishment Park is available on Amazon and Netflix.

Sarah Sze Street View

Just this morning, while I was watching Sarah Sze’s 2010 lecture at the Smtihsonian American Art Museum, and she was showing videos of her installations for the first time [borrowed, with permission, she said, from various YouTube users, which is nice]. And I found myself thinking, “Hah, try running the Google Street View Trike through that!”

But of course, Google already did.

Street View just announced the release of imagery from The High Line, which was apparently captured by the Trike this spring, just before the second, Northern section opened.

And whaddyaknow, there’s Sarah Sze and her crew, installing her bird city, Still Life with Landscape (Model for a Habitat). That’s Sze and her updo on the left. On the LEFT. Focus, people, focus.

And I do believe that is dearly departed High Line curator Lauren Ross with the lanyard, checking in on things. [Happily, Ross isn’t dead; she just moved to Tulsa.]

These photos are actually in reverse order; the Trike was driving south. I haven’t spotted any traces of a Google Guide yet. But I do notice that with this early morning shoot, the Street View pano stitching algorithm erases the Trike’s shadow. Leave no trace.

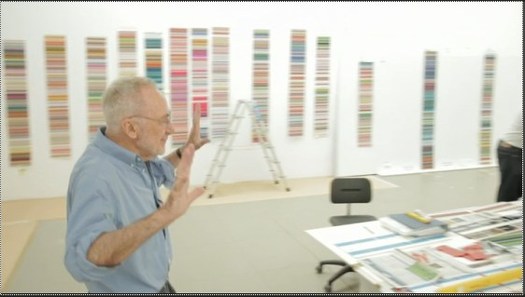

Dazzle Camo Colour Chart

Razzle dazzle camouflage painting was not, as the photographs would have you believe, entirely black and white. [For that matter, neither was WWI itself, but that is a matter for another day.]

In any case, British camoufleur Norman Wilkinson published a camo color chart [sorry, colour chart] in the 1922 edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, which the esteemed camoölogist Roy Behrens re-created using Pantone colors. Sorry, colours.

We had some hints, and Dakis and Jeff already knew about this, of course, but for the rest of us, it’s useful to review.

Roy Behrens’ Camoupedia blog [camoupedia]

Previously: Bedazzled; Dazzle camo design lithos at RISD

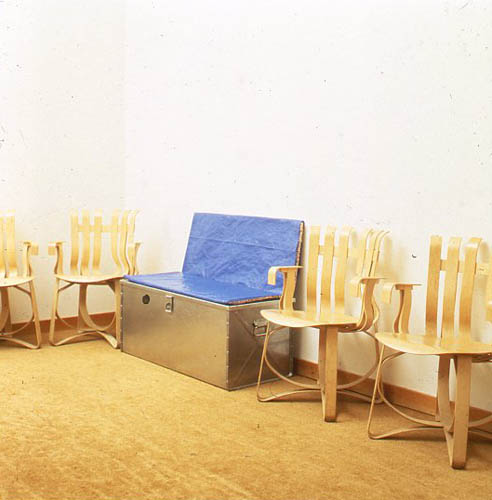

Blue Room And Love Seat, By Jason Rhoades

I love a lot of Jason Rhoades’ work, but only have a little. I wish I’d known about this sooner:

Blue Room and Love Seat is an edition produced with 1301PE’s Brian Butler in 1995, maybe when it was still only 1301.

Anyway, it’s a steel trunk with a cushion on top, for sitting, which contains an inflatable room made from blue tarps. Which sounds delightful, except that it’s inflated by a leafblower, so it’s noisy. And it’s actually inflated by the blower exhaust, so it also pumps noxious fumes into the blue room. Which sort of makes it a portable gas chamber. Which is now kind of depressing.

On the other hand, there must be at least one left in the edition, because the gallery inflated it last year for a show.

Blue Room and Love Seat, 1995, Jason Rhoades [1301pe.com]

“Musée Los Angeles, Blue Room and Love Seat [1301pe blog]

TV Power To The We, The People

A piece I left out of my Rirkrit’s blingy objects post yesterday may be more important than I originally thought, and for more reasons than its shininess.

Untitled 2005 (the air between the chain-link fence and the broken bicycle wheel) was the Guggenheim installation Rirkrit got to do for winning the Hugo Boss prize. It was a low-power, unlicensed TV transmitter, the blueprints for building your own, and wallpaper full of texts about freedom of speech, the revolutionary power of media, and the political and economic contradictions of the FCC.

I was thinking of mentioning it because it atypically included structures made of both plywood and of mirror-finished steel. The glass and steel vitrine held the TV transmitter, the source of media power, while the similarly sized plywood shed contained the antenna and a TV. The steel cube was closed off; the ply cube had a door, windows, and 2×4 furniture. Oh, and an antenna made in the form of Marcel Duchamp’s bicycle wheel.

The instructions for making your own TV station were printed on posters, made available on the floor in a Felix-style stack. If there were a more explicit evocation possible of contemporary art and the political clashes of the 60s, 70s, 80s, and 90s, I guess I can’t think of what it was. Except maybe for Rirkrit’s collaboration the next year with Mark di Suvero to create an Iraq War-era version The Peace Tower.

Untitled 2005 (the air between the chain-link fence and the broken bicycle wheel), detail, via

And then I found Holland Cotter’s unexpectedly extraordinary-in-parts review of Rirkrit’s 2005 Guggenheim show:

The installation is basically a bare-bones statement of the practical fact that anyone who wants to participate in shaping the communications media that are shaping the world at large can do so. “Everyone is an artist” was Joseph Beuys’s potent rallying cry in the 1960’s and 70’s, which made artists and “the people” one. Mr. Tiravanija, who has learned much from Beuys, adds his own variation: “Everyone is a broadcaster. Make this transmitter at home.”

Hmm, mirrored TV: Untitled 2005 (the air between the chain-link fence and the broken bicycle wheel), detail, via

At the same time, he has customized his own version with a couple of features that are not necessarily meant for replication. One is the glass box encasing the transmitter. Its presence is symbolic, a reminder of how resources that should be available free to everyone become the closely guarded valuables of a privileged few.

Yow, that suddenly puts a polemical shine on Rirkrit’s deployment of chrome; makes me not want to get caught with a shiny ping-pong table when The Revolution comes.

But then, in one sense, it’s already here.

The complicated connection between politically charged art of the 00s and today’s Occupy Wall Street protests grew starker as I read Martha Schwendener’s sharp piece in the Voice [thanks, Tyler] about the implications of #OWS for art, and vice versa:

Art was, for a long time, a utopian model. But with bohemianism eroded by gentrification and the 1 percent end of the art spectrum devoted primarily to vapid, overfunded gestures, you wonder if a recent Columbia University symposium, which described art as “a catalyst and platform heralding justice, solidarity, and a peaceful future” is nostalgia–or just wishful thinking.

Schwendener’s piece read to me like a wakeup call for artists: “Practice [sic] is over. This is not a drill.”

Which made me think right back to Cotter’s opening, clear-eyed for a child of the 60s, a reflection on the very idea of “Power to the people”:

Who were “the people,” anyway? Blue-collar workers, African-Americans in the civil rights movement, immigrant laborers. Students? Some, though even engaged young people tended to want to help the people rather than be the people.

There’s a Rirkrit t-shirt in there somewhere, I can just feel it.

Art Review | Rirkrit Tiravanija: Work Whose Medium Is Indeed Its Message [nyt]

What does Occupy Wall Street mean for art? [villagevoice]

Transactional Aesthetics, Or The Highly Collectable Rirkrit Tiravanija

I’ve been writing this post in my head for months, years, even, but so many pieces have piled up in my browser tabs, it’s slowing my computer down. And plus, this weekend MoMA announced that they acquired and will exhibit Untitled (Free/Still), the original [sic] free-Thai-curry-in-a-gallery work, so it’s time to step back and look more closely at Rirkrit Tiravanija’s art practice. First, by starting with what we are fed. Here is a small sampling platter of familiar statements by and about the artist and his work:

“It’s part of what has been called ‘relational aesthetics,’ ” said Ann Temkin, chief curator in MoMA’s department of painting and sculpture. “Joseph Beuys created social sculpture; it’s the act of doing things together, where you, the viewer, can be part of the experience.”

That’s from MoMA’s press release in the NY Times.

You could say his art is all about building “chaotic structures.” Then again, it’s about lots of things; his work is so open-ended and departs so radically from the art market’s orientation toward precious objects, that it’s earned many labels, many – like utopian or chaotic – that only tell part of the story. But one that’s stuck, for better or worse, is French theorist-critic Nicholas Bourriaud’s “relational aesthetics,” the idea of judging the social relationships sparked by an artwork instead of merely considering the object.

That’s Paul Schmelzer, now/again of the Walker Art Center, an early and frequent supporter of Rikrit’s work, writing in 2006.

Tiravanija’s art is free. You only need the experience. In fact, the essence of his work resides in the community, their interrelationships, and chance. Make art without objects, their purpose is a complaint against the possession and accumulation.

The Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León, which owns Untitled (Caravan), a 1999 plywood model of a camping trailer, with kitchen, above.

Rirkrit as quoted by Bruce Hainley in Artforum, 1996:

“Basically I started to make things so that people would have to use them,” he has said, “which means if you [collectors, museum curators, anyone in these roles] want to buy something then you have to use it. . . . It’s not meant to be put out with other sculpture or like another relic and looked at, but you have to use it. I found that was the best solution to my contradiction in terms of making things and not making things. Or trying to make less things, but more useful things or more useful relationships. My feeling has always been that everyone makes a work – including the people who . . . re-use it. When I say re-use it, I just mean use it. You don’t have to make it look exactly how it was. It’s more a matter of spirit.”

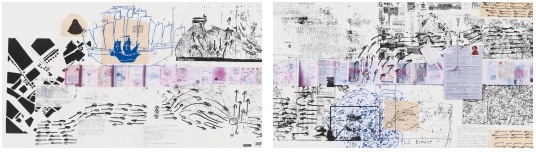

And here’s Faye Hirsch in Art in America this summer, perfectly teeing up her making-of story for Untitled (the map of the land of feeling), [above] an extraordinary 84-foot-long print edition Rirkrit has worked on for the last three years with students and staff at Columbia’s Leroy Neiman Center for Print Studies:

Rirkrit Tiravanija has never been known as a maker of elaborate objects. In a market-riven art world, he has remained, since the early ’90s, a steadfast conceptualist whose immaterial projects, enmeshing daily life and creative practice, have earned him a key role in the development of relational art. At galleries and museums around the world, he has prepared meals and fed visitors, broadcast live radio programs, installed social spaces for instruction and discussion, set up apartments–where he or visitors might live for the duration of a show–and dismantled doors and windows, leaning them against walls. At two of the three venues for his 2004 retrospective, the “display” consisted of a sequence of empty rooms referencing (in their proportions and an accompanying audio) his selected exhibitions over the years.

When Tiravanija does make objects, they are generally of a modest nature–most often multiples and ephemera connected with exhibitions. At his show this spring at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise in New York, for example, he set up a room where an assistant screenprinted white T-shirts with his signature terse, block-print headlines, ranging in tone from vaguely political (LESS OIL MORE COURAGE) to hospitably absurd (I HAVE DOUGHNUTS AT HOME). They cost $20 apiece.

Ah yes, the t-shirts. Not sure if I ended up being the only one, but I was apparently the first to order a complete set of all 24 shirts. So there’s that.

I have been an admirer and follower of Rirkrit’s work since his earliest shows at Gavin’s, and Untitled (Playtime), the awesome, ply&plexi, kid-sized replica of Philip Johnson’s Glass House he built in MoMA’s sculpture garden in 1997 [above] bought him at least a decade of good karma in my book.

And so it’s only very recently that I’ve started to watch and wonder if I’m the only one who– See, this is why Faye Hirsch’s quote is so perfect: because it encapsulates exactly how people talk and write and think about Rirkrit’s work, and it’s perfectly and exactly wrong.

I’m sorry, that’s the overdramatic hook in this post. What I really mean is, as his social, experiential, ephemeral practice, his “art without objects” has taken off, Rirkrit has also been making some of the blingiest, sexy-shiniest, most ridiculously commodified luxury objects around. I love them. Why can we not talk about them more?

Continue reading “Transactional Aesthetics, Or The Highly Collectable Rirkrit Tiravanija”

Here There, There Here, And Everywhere

I’m so blown away by this. RO/LU‘s and welcomeprojects‘ project for this year’s High Desert Test Sites was called Here There, There Here. To call it a contemporary nod to earthworks almost feels backward; it’s like the earthworks movement was building to this.

It’s a two mile [!] strip of white felt run across the open desert outside Joshua Tree. While I was waiting for more photos to turn up, I kept seeing Here There, There Here everywhere:

Richard Long’s 1967 work A Line Made By Walking [spotted on It’s Never Summer, Wayne Bremser’s tumblr]

And then whenever I’d see a contrail across the sky. High fives all around, what a stunning project.

Queen Victoria Silk Newspaper

Well that’s kind of fantastic, like Victorian- era Rauschenberg.

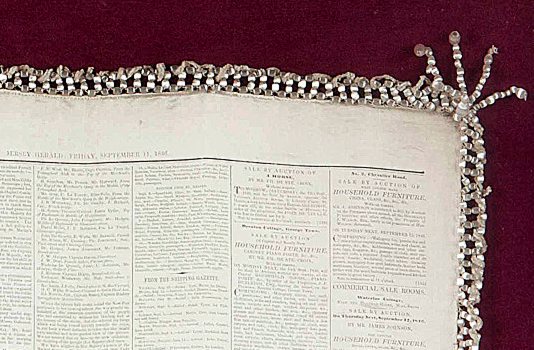

Apparently, to commemorate Her Majesty the Queen’s to the Isle of Jersey, The Jersey Herald printed copies of the September 11, 1846 edition of the newspaper on silk panels, which were then stitched together with beaded pearls. Here’s a detail shot:

Did they only make the one copy? Is this the only printed silk newspaper facsimile out there? Can I find these in any boot sale of dead queen paraphernalia, or only Malcolm Forbes’s?

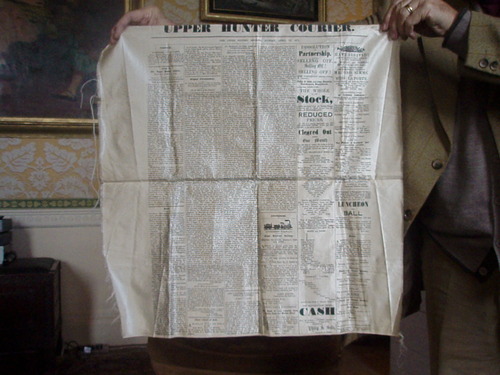

UPDATE AFTER TEN MINUTES OF GOOGLING So printing newspapers on silk is/was a commemorative thing. The first copy of the first issue of the Grand Rapids Times was printed on silk in 1837 and presented to its largest subscriber/investor, while additional souvenir copies were printed on cloth. A silk copy of an 1852 edition of the San Francisco Daily Whig came across book conservator Nicole Wolfersberger’s desk [and into her flickr stream] a couple of years ago. The Upper Hunter Courier made a silk presentation copy of their paper for Lord Belmore after he came to open a section of railway in Scone in 1871. It was not nearly as nice as Queen Victoria’s.

And in 2007, the Jiefang Daily Press Group gave the V&A a copy of the 2005 silk front page which was carried into orbit on China’s second manned space flight.

The Forbes Collection at Old Battersea House – Sale 338 – Lot 415

TWO PRINTED COMMEMORATIVE SILK FACSIMILE NEWSPAPER SHEETS

Est. £500-800 [lyonandturnbull.com]

Previously: Rauschenberg Currents Event

Artforum Reviews Jacob Kassay Press Release

Huh. I guess Artforum’s back-of-the-book review section does not purport to ignore the art market’s overdetermining forces any more.

Ben Carlson’s review of Jacob Kassay’s show this summer at L&M Arts in Los Angeles is framed around the burning question, “Does Kassay’s work properly account for the auction hype and thus, its own presence in this high-end gallery?”

But L &M Arts’ interest in this young painter is no mystery: Regardless of their merit, Jassay’s silvery-reflective monochromes made a splash at auction last fall. Anticipating the cynics, the staff penned a press release that was quick to distance Kassay’s older output from the new work he made for this show. Calling attention tot the differences in surface treatment, it announced that his most recent paintings would feature a “surprising yet deliberate lack of reflection.”

[part where 29-yo Kassay is chided for not taking better hold of his secondary market and is as yet found to be no Ryman or Kelly omitted]

Offered a chair at the high rollers’ table, Kassay could have made only one compelling move–a wager with the potential to break the bank. Of note: His Paris dealer, Art: Concept, has already offered public assurances that the artist is not about to meet the market’s demand for more of the same. In fact, had Kassay overperformed (or overproduced) this summer, he might have presented a distance from these overdetermining forces or even productively embraced them…It appears, however, he’s chosen to ignore them altogether. [ellipsis original]

Some day, maybe the discussion of what we see when we look at Kassay’s distorted, mirror-like work will not be characterized by such a surprising yet deliberate lack of reflection. But that day is not yet.

Previously: On Jacob Kassay and collaboration

#OccupyMarkdiSuvero

Joie de Vivre, Mark di Suvero, Zuccotti Park, detail of image via ourtravelpics.com

Or maybe #OccupyJoiedeVivre, then? Either way, please tell me I’m not the first or only one to think of this. Actually, please tell me someone’s already working on it.

Mark di Suvero’s giant steel sculpture, Joie de Vivre was built in 1997 and stood for several years in the exit plaza for the Holland Tunnel, then at Storm King, and in 2006 it was installed in its new home, Zuccotti Park. Whether its art historical significance is fully appreciated, or whether it’s called “The Big Red Thing,” di Suvero’s sculpture has become an icon of the Occupy Wall Street protests.

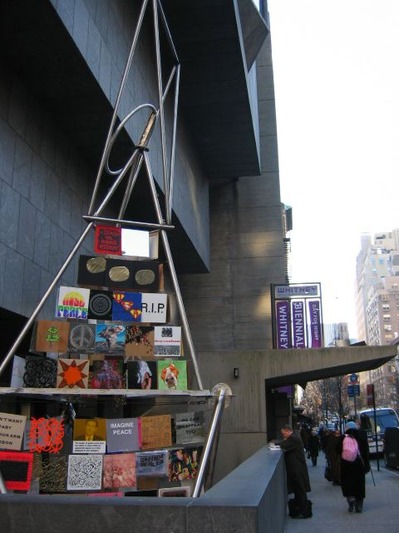

The Peace Tower, 1966, image via newsgrist

Which is good, because di Suvero himself is an icon of artistic involvement in political action, activism, and social justice. In 1966, along with Irving Petlin and others, di Suvero designed The Artists’ Tower of Protest, also known as The Peace Tower, one of the earliest and largest artist-organized protests against the Vietnam War.

The Peace Tower stood on a vacant lot on the corner of Sunset and La Cienega Boulevards in Los Angeles, which Petlin’s Artists Protest Committee rented for three months. They solicited 2×2 art objects from 400 artists, which were installed onsite. Documentation of The Peace Tower is currently included in Pacific Standard Time at the Getty.

Peace Tower @Whitney Biennial, 2006, image via wjff

In 2006, Rirkrit Tiravanija worked with di Suvero and Petlin to re-create The Peace Tower as a protest to the Iraq War as part of the Whitney Biennial. The new tower was festooned with 180 2×2 panels created by invited artists, including many artists from the LA original. [And Joy Garnett, hello!]

So it would seem to me, that when you’re organizing a global protest against injustice at the foot of a Mark di Suvero sculpture, shouldn’t you organize it on the Mark i Suvero sculpture? And shouldn’t you do that, NOT by climbing the sculpture and demanding cigarettes be delivered to you by police cherrypicker, thereby precipitating the fencing off of said sculpture and the park space around it, but by tracking down the artist himself and enlisting him in a call for artists to create 2×2 panels that will be installed on Joie de Vivre itself?

And though it might be hard to measure–or identify, for that matter–the impacts on policy of the war protests in 1966 and 2006, circumstances almost seem to demand an incarnation of a protest tower in 2011-12. And at the very least, art people, doesn’t this make 10000x more sense than marching on the Frick?

Related: Jeffrey Kastner’s remarkable interview with Irving Petlin, Mark di Suvero and Rirkrit in the March 2006 Artforum [artforum via findarticles]

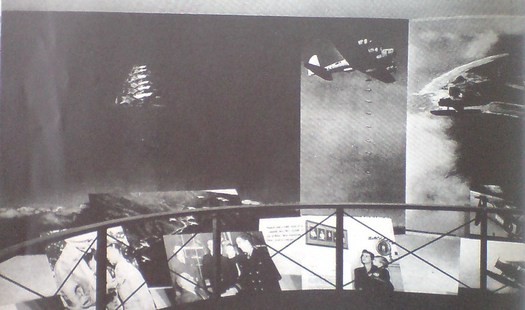

On Gerhard Richter And Comdr. Edward Steichen

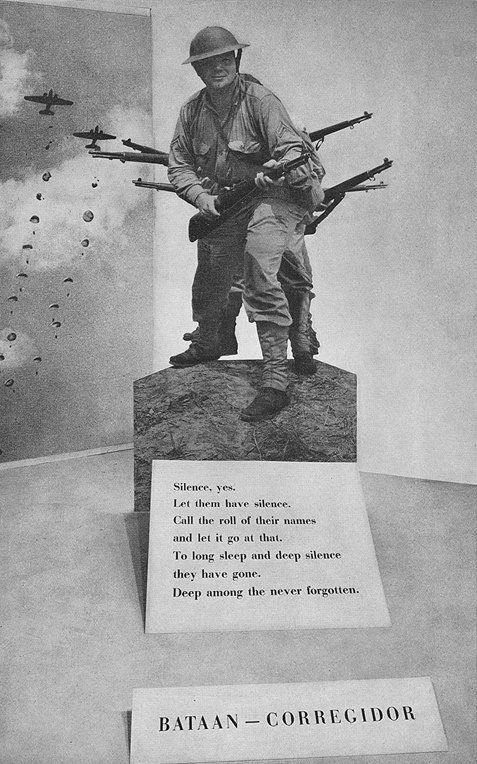

See, this is why I wonder about whether Gerhard Richter, “shocked” by seeing Edward Steichen’s MoMA exhibit Family of Man in West Berlin in 1955 while he was a student, ever went on to research Steichen’s earlier photography exhibitions, such as the 1942 Road To Victory.

Because all around the life-size photo cutout of a GI on Corregidor is a whole series of giant aerial photos of US bombers and fighter planes at work. Over the skies of Germany.

And though Atlas shows Richter took a specific image from a newspaper for his first airplane painting, it does look very much of a type–and of a scale–that Steichen was using, too.

Bombers, 1963, image: gerhard-richter.com

And then this one which, like the one behind the cutout, is clearly taken from the ground–and, just as clearly, from the business end of a bombing run:

Airplanes, 1963, image: gerhard-richter.com

Loads of death, tons on tons of annihilation, out of

the sky and down down down on the enemies of

the free world–killers with wings–dropping

polished cylinders to let loose tornadoes of hell

and ashes on the hideouts of the “New Order.”

Carl Sandburg’s rather plush poem/captions for Road To Victory sound a little different in this context.

In comparing photography’s postwar cultural positioning to the prewar modernist era in relation to the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher, Blake Stimson wrote,

Photographers once again assumed a special role for this reconstruction, this production of a new, new vision and new, new man. Such was the mission adopted programmatically by Edward Steichen for The Family of Man, for example,

So whatever Family of Man‘s photographs may have told Richter “about modern life, my life,” once he came West and started painting, I’m not so sure he was still buying it.

Gerhard Richter On The Family Of Man

The Tate video of Nic Serota and his team in Gerhard Richter’s studio is nice for many reasons: it includes some squeegee action scenes from Corrina Belz’s Gerhard Richter Painting [which I’m trying to get a copy of; Is there anyone in London who can pick up a DVD for me? Or in the UK anywhere who can accept a shipment and forward it onto me?]

For filming, they moved the model of Tate Modern’s galleries into the main studio room, which was full of strips of the Strips series [and hey-ho, a bent strip too, what’s up with that?]

But the most interesting thing to me, anyway, is this exchange from Serota’s interview of Richter, about leaving East Germany:

GR: We had also the possibility to go every a year at least twice to West Berlin, to saw movies and exhibitions. It was the first time I saw the wonderful Family of Man

it was a famous exhibition.

NS: This was the exhibition made by Edward Steichen

GR: Uh-huh, and this was a real shock for me, this show.

NS: Why?

GR: Yeah, so, to see these *pictures,* and I only knew paintings, I was very interested. And they showed so much, and they told so much, these pictures, these photographs. They told so much about modern life. my life.

NS: So was this the moment when you discovered photography? Or the power of photography?

GR: Let’s say the power, yeah, of what photography can do.

Serota delivers that question with an intensity that makes it feel like a scoop, and I don’t think his reaction is [just] for the camera. I haven’t found any previous mention of Family of Man either by Richter or in relation to his work. Steichen isn’t in the index for the collected writings. There’s no mention of it in Christine Mehring’s study of Early Richter. And though Elger’s bio for the period in question–Family of Man opened 17 September-9 October 1955 at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste–mentions Richter’s trips to West Germany during what was his last year studying mural painting at the Academie in Dresden, there’s no mention of the photo exhibit itself.

Serota delivers that question with an intensity that makes it feel like a scoop, and I don’t think his reaction is [just] for the camera. I haven’t found any previous mention of Family of Man either by Richter or in relation to his work. Steichen isn’t in the index for the collected writings. There’s no mention of it in Christine Mehring’s study of Early Richter. And though Elger’s bio for the period in question–Family of Man opened 17 September-9 October 1955 at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste–mentions Richter’s trips to West Germany during what was his last year studying mural painting at the Academie in Dresden, there’s no mention of the photo exhibit itself.

As for Richter’s nascent interest in photography, the artist did tell Rob Storr that he received copies of Magnum magazine from an aunt in the West. And Elger notes that his family photo album was “one of the few belongings Richter would take with him when he fled to the West.” But the artist now adds Family of Man to the list of his early photographic influences. It makes me wonder what the show actually showed Richter about photography’s power, and whether the artist went on to study Steichen’s other MoMA photo exhibits, the ones that didn’t travel to Berlin.

Image above: Edward Steichen in the Berlin installation of Family of Man, 1955, via moma.org

Tate Channel | Gerhard Richter (21:58) [tate.org.uk via @aodt]

Previously: The Family of the Family of Man: Steichen, Miller, Rudolph, Stoller