I’m sure photomural historians out there are chuckling, wondering when I was finally going to catch up on this, but

HOLY CRAP, PEOPLE! ANSEL ADAMS PHOTO MURALS!

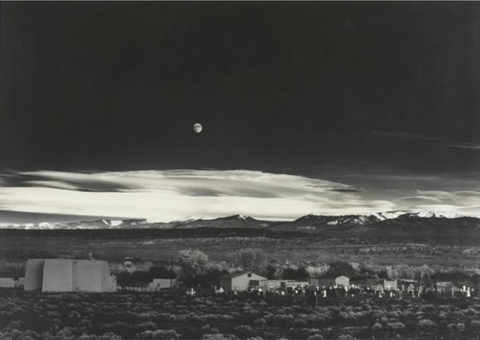

Alright, it’s not quite so unknown. The Polaroid ransacking auction last year at Sotheby’s included a very large print, what Adams called “mural-size,” of the photographer’s iconic image, Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico.

But The Mural Project was actually an Adams thing, a series of images commissioned by the Department of the Interior. Adams traveled around the US, shooting–he took Moonrise on the same trip, and because he hadn’t expensed that day, the photo was his, not the government’s. World War II derailed the project, though, and it was sort of forgotten. Until last year, apparently. When Adams’ original prints were rediscovered in a file somewhere [really?? looking into it. Hmm, this book of the images, which are now in the public domain, was published in 1989.], Interior Secretary Ken Salazar gave the OK in 2010 to install full-scale versions of The Mural Project for the first time. They’re still there, at the Interior Dept Museum. Viewing them requires a reservation.

Adams wrote an essay/letter titled “Photo-Murals” for the November 1940 issue of U.S. Camera [looking into it] in which he argued for large-scale prints, permanently mounted on panels, over wallpaper-style murals. He made such “mural-size” prints for the lodge at Yosemite, and for various exhibitions, but he also took orders for large prints. Most were smaller, around 40×60, but they did get bigger, up to 6×9 feet. The 2003 show of monumental Adams photos Andrew Smith Gallery spent ten years assembling included one such 6×9 print.

But not a screen. Because apparently Adams would occasionally make photo screens, giant prints on multi-panel, folding screens. Which, what?

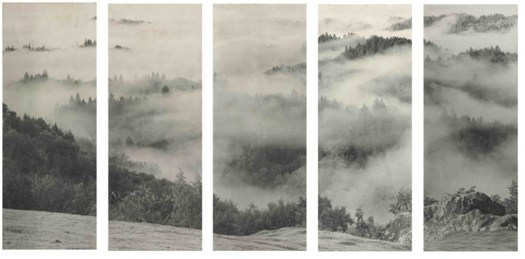

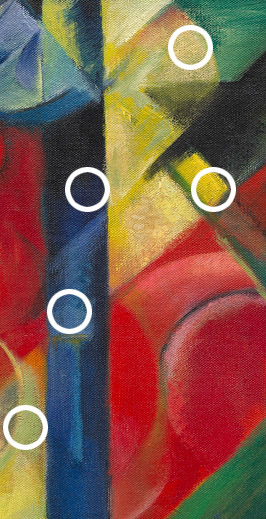

Clearing Storm, Sonoma County Hills, image via christies.com

He didn’t make very many, though; when they sold a big, awesome 1951 screen a couple of weeks ago, Christie’s said there were between 12 and 15, mostly in museums and the Adams Estate. Apparently, he sold one to Interior Secretary Harold Ickes in 1935, though, a deal which according to biographer Jonathan Spaulding, led to the Mural Project commission.

The screen he made for the Skirballs originally had an image on each side; the lot description says how when Jack Skirball invited Adams to come visit in 1981, they were “most anxious to have your opinion on what Audrey has done with the panels of the screen. I don’t want to tell you more until you see them.” It sounds like she remade them into a set of five one-sided panels. No word on what she did with the other image–or what Adams’ reaction was. Even so, the ex-screen sold for $242,500.

Though Adams was always very cognizant of the particular physical qualities of his prints, these screens seem to pose an entirely different argument for the concept of photo-as-object. If murals are related to frescoes, and “mural-size prints” evoke paintings, then Adams’ photo screens–printed to human scale, mounted in angled strips, freestanding in space, where they are intended to be viewed and experienced by moving around them–are akin to sculpture. Photographic sculpture.

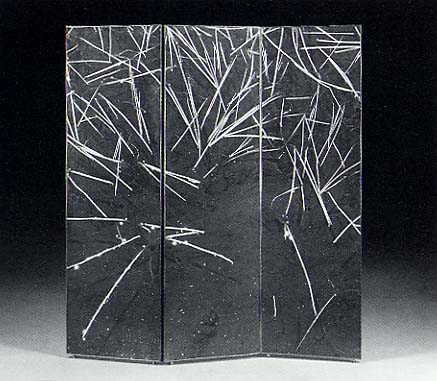

Or maybe they’re also sculpture. Because check out this one, Grass and Pool, a three-panel landscape photo and abstract action painting and freestanding object, all in one, and made in 1935. Oh wait, never mind. The image is from 1935, the screen is from the mid-50s. No need to rewrite the history of abstraction today. It was made for David McAlpin, a banker and collector who, as a trustee at MoMA, helped found the photography department in 1940.

Grass and Pool, sold in 2001 at Christie’s

Adams talked at length with Ruth Teiser about his photomurals and screens–actually, he talked at length with Teiser about everything; she recorded and edited 24 interviews with Adams between 1972-4 for UC Berkeley’s Regional Oral History Project, and later published the 818-page transcript as Conversations with Ansel Adams.

I transcribed some excerpts about photomurals from the Internet Archive after the jump. Adams’ main concern was the quality and character of large-scale prints, a topic which regularly veers into details of what an expensive, annoying, labor- and material-intensive pain in the ass it was to make good, big work.

Continue reading “How To Make An Ansel Adams-Style Photomural / Folding Screen”

People come to an art museum in part to be inspired by the works of art on view there. And we develop an emotional relationship with those works of art and with the artists that created them.

People come to an art museum in part to be inspired by the works of art on view there. And we develop an emotional relationship with those works of art and with the artists that created them.