As part of Rotterdam 2007 – City of Architecture, the city commemorated the 15-minute-long German bombing on May 14, 1940 that destroyed the city center, precipitated the Dutch surrender in WWII–and ultimately provided the occasion for all that new architecture. The area destroyed by the bombs and the ensuing firestorm is demarcated by the Brandgrens, or Fire Limits:

The Fire Limits

14.05.2007

On Monday 14 May, in the evening, Rotterdam 2007 City of Architecture will illuminate the fire limits of Rotterdam’s city centre with over one hundred light beams.

The fire limits mark the areas of the city that were destroyed by the bombing on 14 May 1940 and the ensuing fires that broke out. From 10.45 pm a blaze of light beams on these boundaries will light up the skies, making the true impact of this devastating event visible throughout the entire city.

The bombing ‘only’ lasted fifteen minutes but managed to destroy practically all of Rotterdam’s city centre. Even before the war ended, it was decided not to replicate pre-war Rotterdam when reconstruction began, but to turn the city into a modern, revitalised city. The fire limits highlight the differences between the old and the new in many places in the city centre, which although visible, have never been experienced as a whole before. On 14 May 2007, the art producer Mothership will illuminate the entire fire limits, stretching almost 12 kilometres, turning this historic event into a sight that everyone can see.

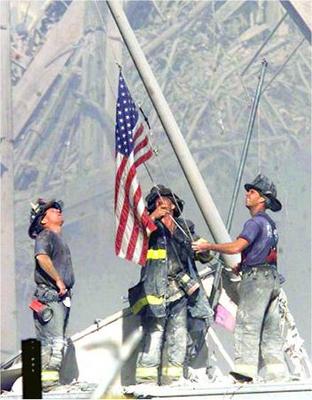

Such a prominent spatial use of spotlights as a memorial these days obviously evokes references to the Towers of Light memorial. Like the World Trade Center version, this project, produced by the art collective Mothership, is intended as a temporary, ephemeral precursor to a permanent memorial demarcating the Brandgrens. But that’s actually not the most interesting part of this project for me.

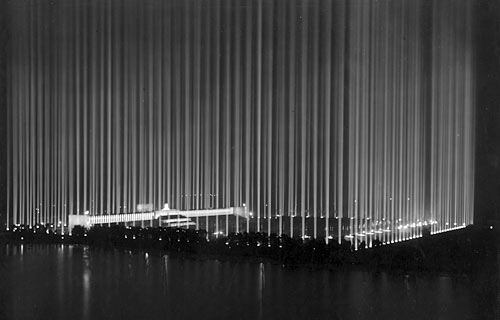

Though the memorial’s official path through the city was only recognized in February, the idea of the Brandgrens has been as integral to the post-war identity of Rotterdam. The Fire Limits [or as Mothership translates with a bit more thesaurian flair, Bombardment Periphery; Babelfish translates Brandgrens as “Fire Boundaries”] is a commemoration of a Nazi attack that uses the Nazis’ own vocabulary of spectacle, specifically Albert Speer‘s 1934 Lichtdom, the Cathedral of Light, at Nuremburg. The rendering [above] reads almost like a direct quote of Lichtdom, in fact.

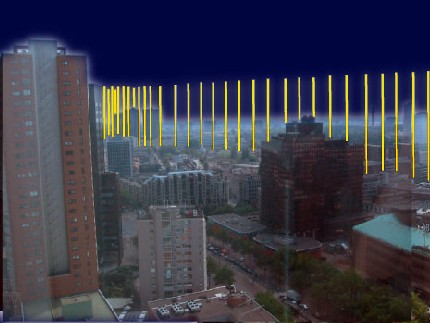

As it turned out, Bombardment Periphery looked uncannily like a re-creation of a nighttime bombing, with evocations of anti-aircraft searchlights, groundlevel glow, and illuminated cloud cover. I’d be very interested to hear what the reaction was to this event [the commemorating, that is, not the attack.]

It’s a bit absurd, but the first image that comes up in my search for night-time air raid photos was from Los Angeles.

In the early morning of February 25, 1942, unidentified flying objects were spotted over Los Angeles, triggering a massive anti-aircraft barrage that killed three civilians [three more died of heart attacks] and sparked a flood of bitter criticism and controversy. No definitive explanation has ever been made of the objects. The incident was inspiration for Steven Spielberg’s comedy [sic], 1941.

The caption for this photo, which ran on the front page of the LA Times, is incredible:

Scores of searchlights built a wigwam of light beams over Los Angeles early yesterday morning during the alarm. This picture was taken during blackout; shows nine beams converging on an object in sky in Culver City area. The blobs of light which show at apex of beam angles were made by anti-aircraft shells.

The obvious question, of course: Is next February 25th too soon for someone to recreate a wigwam of light beams over Culver City?

Bombardment Periphery Gallery [enterthemothership.com]

Rotterdam2007: The Fire Limits [rotterdam2007.nl]

West Coast Air Raid [wikipedia]