hello? Is this thing on? (sms posting) some gd disc 2 day, & nice emails re the movie. Thnx (gotta go. Opening. )

Sergeant! Take this back and gimme that Titanic CD instead

According to this Washington Post article [via Boing Boing], Whitney Houston’s “I Will Always Love You” is Sadaam Hussein’s campaign theme song for today’s presidential referendum. Before it became a the most popular Valentine song in England, it was the love theme for The Bodyguard. I imagine somewhere in the Pentagon, a psyops playlist is being revised; Whitney’ll have to find some other way of contributing to the (Bush, not Husseini) war effort.

With Houston off the (turn)table, I wondered what does Operation MC Hammer play? Most accounts of the 1989 US invasion of Panama universally mention just generic “rock music” or “hard rock music”; in Iraq I, it was “grunge and death rock”, but actual bands and titles are hard to come by. But not impossible. And the throwaway labels, “rock” and “grunge” turn out to obscure more than illuminate the actual operations.

Piecing together the US Military and FBI Psychological Warfare Compilation Tape, it seems that they’re programming more for themselves, not for their opponents. Like Robert Duvall’s Col. Kilgore in Apocalypse Now, who clearly relishes the Wagner he blasts out of his chopper, when the ATF plays “These boots were made for walkin'” in Waco, it’s just a morale booster for their own guys. (Did it drive Koresh mad? Wasn’t he already there? And how many people actually put on those boots and walked out?) When it comes to psyops, you have to wonder whose heads are really being messed with.

The playlist so far:

[Correction: Two readers–neither of them Sandy Gallin–wrote to demand credit be given to Dolly Parton for that Whitney song. They were more worked up than the Klingons who corrected my (only other) previous error (ever). With fans like that…]

Well, I’ll be damned, or How Norman Mailer IS The Center of The Universe

Had a man been always in one of the stars, or confined to the body of the flaming sun, or surrounded with nothing but pure ether, at vast and prodigious distances from the Earth, acquainted with nothing but the azure sky and face of heaven, little could he dream of any treasures hidden in that azure veil afar off.

– Thomas Traherne, The Celestial Stranger, mid 17-th c.

Effusively compared in this Guardian article to the Apollo astronauts’ first views of the earth from space, Christian mystic Thomas Traherne’s writing “can turn your understanding inside out, thrill, surprise and exhaust you” with his revelatory view of the world.

This is a review of Ronald Weber’s 1986 book, Seeing Space: Literary Responses to Space Exploration (Amazon Sales Rank: 2.2 million. Let’s help the guy out.) which wonderfully uses the last line of Thoreau’s Walden to identify the greatest impact of space travel: ” ‘Our voyaging is only greatcircle sailing.’ This is to say that the most important aspect of our travels, whether inward or outward, is that they bring us back to our point of departure with a new appreciation of that beginning place.”

Norman Mailer begins with a complaint that the whole space thing is closed to him: since he can’t talk the techno talk or get inside those astronauts’ heads, all he can do is watch dumbly “from the visitors’ bleachers.” He has an epiphany at the crassly commercialized Plymouth Rock (where only “an immense quadrangle of motel” marks the hallowed spot), and sees the Moon Rock anew. The whole adventure represents “the…reawakening of an older and non- mechanical view of life, one in which we are brought to ‘regard the world once again as poets, behold it as savages.”‘

These ecstasy-riven testimonies– utterly self-contained, yet reaching out to (potentially) affect us all, something we must accept in imperfect transmitted form (unless you’re John Glenn or Lance Bass. Actually, being Lance Bass doesn’t do any good, either.)–may help in understanding Matthew Barney’s Cremaster Cycle.

This seriously ecstatic Guardian review (What IS in that tea, fellas?) attempts to affix Barney’s work in the heavens. It is an omniscient, mysterious creation myth, ultimately incomprehensible to mere mortals. It is at once “dense,” “rich yet fragile,” “of our time,” and “aspiring to be eternal.”

Like the “great American novels” (Moby Dick and Gravity’s Rainbow are mentioned), Cremaster embodies the “desire to reawaken the language and imagery of ancient, organic patterns of thought [which is] central to modern American art and literature.” Heady stuff. And there’s Norman Mailer again, right in the thick of things, starring as Harry Houdini in Cremaster 2 (the most successful of the series, IMHO). But for all the praise and allusion heaped on it, does Cremaster take us “greatcircle sailing?” What does it say about the place we return to after seeing it?

In Artforum, Daniel Birnbaum argues that “no one makes a stronger case than Matthew Barney for visual art today.”

All that the world most needs today is combined in the most seductive way in his art: Barney’s work is brutal and highly artificial, as Nietzsche came to think Wagner’s was, yet it also offers up the pure joy of the beautiful–which is, I think, not unrelated to what Nietzsche meant by “innocence.”

Whatever Barney’s goal, his achievement is notable. But at what price? Buzz Aldrin wrote candidly of his most significant challenge: dealing with life after returning from the moon. His goal accomplished, his life suddenly lacking direction, his marriage unravelling, he grew frustrated that “there is no experience to match that of walking on the Moon.” For Barney’s sake, I hope he doesn’t mimic Aldrin too closely, cursing his own hairy moon on the screen, “You son of a bitch, you’re the one that got me in all this trouble.”

On Invention learning who his mother is the hard way

to

to

Finished the MemeFeeder project on time. The scene I thought I’d do turned out not to be the scene I’d actually been asked to do, although I only saw the email with the actual scene assignment yesterday. So, no sooner did I complete the shoot, then I found out I had to do it all over again, with a scene I’d never thought about. And, I’d have to do it in <1 day. This, after I completely rethought and shot the 1-minute scene (#3, titled “Commute”) and shot it in a way that 1) didn’t require going to CT and JFK; 2) didn’t require editing, since my Final Cut Pro computer wasn’t available enough, 3) fit the images in the storyboard, and 4) would be interesting. Wanna see what I came up with? Watch it here. (It’s a crappy 1.1mb quicktime file).

to

to

So, I had about 12 hours to come up with the scene above (#7, titled “Escape!”), with all the restrictions above, and on a cold rainy night. So I took a different take on the title, “Escape!” The story is, well, it’s pretty self explanatory. I am pretty happy with it, frankly. I edited it entirely in the camera (using only the “Record” button). Watch the scene here (again, in crappy quicktime).

I have no idea what the MemeFeeder folks’ll think, but you should definitely check out the completed project (which launches Monday, Oct. 14). It’s been nervewracking, but a lot of fun.

On the influence of contemporary art on film, or Gurskyspotting

99 Cent, Andreas Gursky, 1999

Watching Paul Thomas Anderson and Adam Sandler discuss Punch-Drunk Love on Charlie Rose. The overly bright 99-cent store in the clip looked familiar, eerily familiar, and, sure enough, it is the same as Andreas Gursky’s photo99 Cent, down to the giant “99-cents” banners on the back wall.

Anderson also tapped Jeremy Blake to create abtracted hallucinations experienced by Adam Sandler’s character. Although Blake has become best known for his digitally animated abstractions, he is also quite fluent in film; he exhibited an illustrated screenplay, props, and digital “set” renderings in his first gallery show and has created at least one narrative animated short. [Thanks, Travelers Diagram.]

Mark Romanek used a Philip-Lorca diCorcia photo to communicate to Robin Williams his character’s situation in One Hour Photo. “This is everything in terms of warmth and connectedness that your character can never have but desperately would want.” Judging from the pronounced lighting and extremely deliberate framing of the scenes I’ve seen, diCorcia references are not just limited to mood or motive.

While you could chalk up the Bruce Weber-ish look of American History X to the general zeitgeist (If you’re shooting muscly, shirtless Aryans in 1998, whose style would you appropriate?), it’s something else when “important” but certainly not mainstream artists’ work turns up. I don’t know what that something is, though, and it’s 1:30 in the morning, so I doubt I’ll figure it out right now. I do know that we’d call the throwaway-sublime landscapes Richters, (but we were just kidding, I swear). And Jonah’s shots got called Vermeers (or Vermers, to be precise) by a woman at our hotel in Albert.

On Arches, Now and Then

The architect Renzo Piano is conspicuously absent from both the discussion and the process of rebuilding New York City. Conspicuous because he has already designed Manhattan’s next important skyscraper, the headquarters for the NY Times [see the model]. Conspicuous because he is clearly one of The Times’ critic Herbert Muschamp’s favored architects (“Piano is a humanist, perhaps the leading exemplar of that tradition in our time.”) Conspicuous because he developed the master plan for what is the only recent urban undertaking of comparable scale, Berlin’s Potsdamer Platz. Conspicuous because his innovative, forward thinking design for extremely conservative clients (the followers or the controversial saint, Padre Pio) is being hailed as a miraculous masterpiece by the Guardian before it’s even completed. (That Muschamp link above praises it, too. While I like Kansai Airport, my favorite Piano work is still the Menil Collection in Houston. It’s subtly but completely transformative.)

For this massive (6,000-person) pilgrimage chapel, Piano reinvented and reinvigorated the use of the arch–specifically the stone compression arch–a technique with a 2,000-year old legacy. Another interesting characteristic is the building’s discrete siting; “In fact,” Piano says, “it will not be visible until visitors are very close.” These remind me of another “pilgrimage site.”

Memorial to the Missing, Sir Edwin Lutyens, 1932

Lutyens’ Memorial to the Missing at Thiepval has been called the “most imaginative and daring use of the arch form.” According to Alan Borg’s War Memorials, the venerable Lutyens took a thoroughly modern approach to an ancient form, infusing the Roman triumphal arch with the essence of even more ancient burial mound architecture. And like Piano’s chapel, the Thiepval memorial is meant to reveal itself (and its lesson on the wages of war) only gradually.

Last December, according to Muschamp, Piano said the architects who could design well for Ground Zero are now only 4 or 5 years old. I don’t think that’s right. Piano also said, (rightly) “Whatever is built, there should first be a great deal of thought and reflection. It’s not only an economic issue but a cultural one. What is at stake is saving the soul of a city, its spirit.”

Lutyens completed Thiepval nearly 14 years after the war ended; he was in his sixties. Considering it’s the exact opposite idea I had when I decided to make a movie about Thiepval, I surprise myself. I wonder if what Manhattan needs is a Lutyens, and if Renzo Piano is it. I hope I’m wrong, because he’s nowhere near the place.

On how I always think I have two more days than I do, sort of a staggered Groundhog Day

Sent off entries to festivals in Rotterdam and San Jose, even though Rotterdam’s short film deadline was last week (I got as close to special dispensation as they’re willing to do in these circumstances, pleading and dropping the heavy name of the festival that accepted the film for December.)

The memefeeder online film project doesn’t have a upload deadline Monday, it goes live on Monday, so I’m scrambling to shoot, edit, digitize and upload that by Friday night. Net net: the storyline I posted a couple of days ago may only be released on the DVD…

There are a lot of thanks to give out. First, Evan of Blogger, who kindly annointed this site and brought it to the attention of some people besides those Googling “Albert Maysles and Glitter“; travelersdiagram, Ftrain, Camworld and boing boing, where I’ve tapped some rich info veins lately; fellow filmmakers Ryan Deussing, Stefan DeVries, and Roosa, who’ve said very nice things; folks at themixture.com, who were also very kind; Tyler at MAN, whose site is a great read despite all the comments I post on it; Eric Banks and Nico Israel at Artforum for alighting (from the heights of print) on the net for a good exchange.

If all these thank you’s sound elegiac, don’t worry; I’m only going to the gym.

Memefeeder scene preparations

to

to

Currently prepping to shoot a 1-minute scene for an online collaborative film at Memefeeder.com. I’m doing Scene Three, “Commute,” for which the first and last shot of the scene has been provided; what actually happens in the scene is up to me.

The story: previous instances of missing his ride flash through the mind of a commuter worried about being late once again.

shot 1: a failed attempt to hitchhike in Greenwich, CT

shot 2: missing the bus

shot 3: searching unsucessfully for a cab

shot 4: missing a flight at JFK

shot 5: running for the closing subway doors

Web links I’m using: Planespotting.com’s JFK runway guide, Cached maps of JFK. Apparently, original map images have been removed from the web. No telling yet if the planespotting roads are still accessible. The Pan Am (now Delta) terminal’s rooftop parking most certainly is not

Porn (‘n Chicken) on the Internet? What’ll they think of next?

James “Sweet Jimmy the Benevolent Pimp” Ponsoldt was a co-founder of Porn ‘n Chicken, a Yale timekiller-cum-media spoof-cum-Comedy Central movie. (If that sentence doesn’t get this weblog banned by your corporate firewall, it’ll at least get you a reprimand at your performance review.) Tad Friend’s New Yorker piece contains Jimmy’s description of his latest project:

“It’s ‘Long Day’s Journey Into Night’ set in rural Appalachia,” he said, “with themes of rifts between generations, loneliness, becoming a man, and OxyContin addiction.”

Sound familiar? It took me a second, but it’s Cyan Pictures’ Coming Down the Mountain. Despite what the title may lead you to believe, it has nothing to do with Porn or Chicken. [For fun, try and match the other porny aliases in the article with the crew at Cyan!}

Readin’, Ritin’

Took a couple of short breaks from writing the as-yet unannounced animated musical (henceforth, AYUAM), just to read the paper:

K&K’s process: “Mr. Piesiewicz would propose an idea, he said, and then he and Kieslowski would collaborate on a short-story-like prose version of the eventual script. Then Mr. Piesiewicz would write the screenplay, with ample input from Kieslowski.” Heaven was in the short story stage. Kieslowski’s films have topped my list of influences and inspirations for a loong time. (search the site for Kieslowski, or go to the complete movie index for references. And I met Tykwer in 1999 when he was in the US for the run of Run Lola Run. Nice guy. very low key, very smart, and pretty old for a new director, something I don’t think anymore, obviously. Bonus: The article includes a handy pronunciation guide for all three men’s names. Clip it and put it in your wallet for party talk.

Well, early to rise, at least

Joseph Smith Sphinx, Gilgal Garden, Salt Lake City [image via pjf]

Unable to stay asleep, I read Paul Ford’s excerpt of Benjamin Franklin’s autobiography, wherein I learn that Franklin’s worth more than a Benjamin. At age 79, he recounts his clearheaded pursuit of Moral Perfection, determining that:

on the whole, tho’ I never arrived at the perfection I had been so ambitious of obtaining, but fell far short of it, yet I was, by the endeavor, a better and a happier man than I otherwise should have been if I had not attempted it; as those who aim at perfect writing by imitating the engraved copies, though they never reach the wished-for excellence of those copies, their hand is mended by the endeavor, and is tolerable while it continues fair and legible.

Since it’s much more fun to get (morally) high together, I invite you all to listen in to the semi-annual General Conference of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints which takes place this weekend. A well-spoken crop of 79-year olds (give or take a few years) will be imparting the Word from The Pulpit.

This in turn brought to mind the shiny corporate newness of the giant conference center that recently usurped the more famous Tabernacle as the official seat of the Conference. And for a moment, I was sad to see only one Google citation of my preferred name for the center, the Meganacle.

And which kindred wordsmith, laboring alone until now to propagate this term, accurately points out the building’s resemblance to ancient Babylon or “government buildings constructed during Franco’s era in Madrid?” Terry Tempest Williams, who’s more Word Whisperer than wordsmith, I guess.

Lacking a serene slate terrace and a morning dew-covered chair from which to watch the fawns scamper, I’ve never read TTW’s books. (Although they sure love her over on the NPR.) But this essay–which includes an interesting story of visiting her ancestors’ graves and “sharing genealogies, a typical Utah pastime,” with fellow cemeterygoers–also gives a great deal of attention to Gilgal Garden, a brilliant and unusual work of Mormon artistic expression I’d always thought we weren’t supposed to talk about. See more photos and the original brochure.

“Don’t rebuild. Reimagine” (as applied to writing an animated musical feature)

My attention has been turned to the as-yet-unannounced feature I’m writing (unannounced because of the desire to confirm clear ownership of the story, because it’s freakin’ brilliant, and because there were some major plot questions in turning it into a kick-ass movie), an animated musical. On the train down to DC the other night, I had a breakthrough, facilitated by my decision to rewrite the script from scratch instead of waiting for the data-recovered version to arrive (or not) from my dead hard drive.

This take-it-from-the-top approach opened the floodgates, let all the pieces fall into place, whatever the metaphor is, it’s working. I laid out all of Act I, have about half the dialogue for Act I, and am now deep into Act II, which is unfolding in my brain with unexpected clarity. Within a couple of days, I should have a completed draft/outline, with some scenes, dialogue, and detail worked in. The questions, problems, or plot points that are still unresolved (or that arise from here on) should be pretty manageable. In a nutshell, it feels great.

Just to show how deluded and misplaced my confidence is, here is a footnote I put at the end of the first paragraph. “Opening scene refs: Aeon Flux; Matrix, Star Wars, War Games, Snow White, Minority Report, Austin Powers, Terminator, a pile of RPG and FPS games.” The Star Trek IV, Sound of Music, and West Side Story references don’t show up until later.

“If I am lonely in a foreign country, I search for ruins.”

The quote is from Christopher Woodward’s book, In Ruins, which was sensitively reviewed in the New York Times. Cited near the end of the review, the line resonated with both the story in my short film Souvenir and my own experience. It reminded me of an overheard comment from almost exactly a year ago, “I just wanted to be a part of it.” The great part of Woodward’s book deals with the “pleasurable pain” ruins evoked as late as the 19th century, when “modernizing” civilization finally yielded a city larger than 4th century Rome or a building larger than the Colosseum.

In the Somme (where parts of Souvenir take place), there are almost no ruins. Unlike Verdun, which the French quickly covered with a bell jar of remembrance, the Somme was pretty much rebuilt, monumented, or plowed under. In reviewing Woodward’s book, Richard Eder writes that modern society (ie., weapons+tactics+building technology) may have made ruins obsolete, to our detriment: “With nuclear weapons or box cutters we are able to annihilate the past as well as the present.”

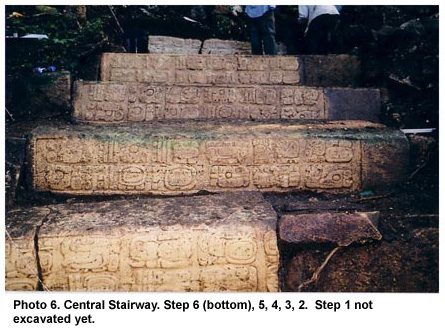

In the review (and presumably, in the book, too), these lessons don’t really jump out, but instead come into view, like a Mayan temple engulfed by the jungle. On September 10th, archeologists reported a major discovery, carvings that reshape the history of Dos Pilas, a Mayan ruin in Gautemala. The carvings came to light after the country suffered widespread devastation last year from Hurricane Iris. Sometimes it’s only in the aftermath of destruction that modern society even thinks to learn lessons from the past. Or as Woodward puts it, “When we contemplate ruins, we contemplate our own future.”

Nothing but blues, guys. (Can I see?)

Like I said, the British…

Every once in a while, I remember that the Guardian has this thing called The Digested Read, where books are reviewed in the style of the book itself. I’m sure every review sends some British demographic laughing to the floor, but with my limited book learnin’ I can only understand a few. Some favorites: