Not sure what this psychedelic Juddy chair/sculpture colabo they're doing with Eric Timothy Carlson is about, but anything RO/LU does has my undivided attention, even if they didn't quote my favorite Joe Bradley review. [via rolu]

January 30, 2011

Not sure what this psychedelic Juddy chair/sculpture colabo they're doing with Eric Timothy Carlson is about, but anything RO/LU does has my undivided attention, even if they didn't quote my favorite Joe Bradley review. [via rolu]

January 30, 2011

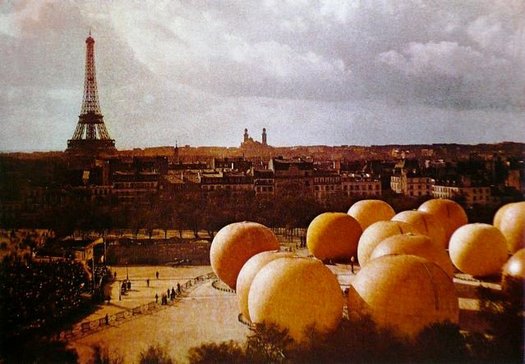

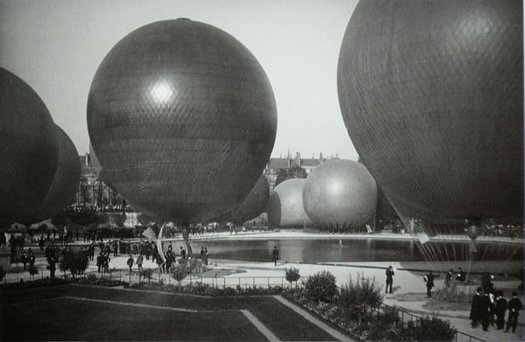

Last week in my interview with Mike Maizels for Pinkline Project, I'd mentioned how the Grand Palais in Paris would be an acceptable art venue for exhibiting my satelloon project. Not only was the grand nave one of the few spaces in the art world that could accommodate a 100-foot diameter inflated aluminum sphere; but historically, it was the site of major, early air shows, and it has held giant balloons before.

As new greg.org reader Erik points out in this awesome color [!] photograph, which was taken in 1909 by Léon Gimpel.

I didn't know Gimpel, but the Musee d'Orsay says I should be as familiar with his work as with his Belle Epoque confreres Lartigue and Atget. They staged a retrospective of Gimpel's pioneering photography in 2008. Apparently, he experimented with distorting mirrors, perspectival compositions, and color photography. He published the first color news photo, using the Lumieres' autochrome technology [the same as above] just days after they introduced it. And though I can't find examples of it yet, his aerial photography sounds pretty sweet:

From 1909 onwards L'Illustration commissioned photo reports directly from Gimpel. He stood out from other photojournalists by producing unusual images. At the first major air show, held at Béthény in August 1909, he went up in an airship and so was able to photograph the progress of the aircraft, not from the ground like the other photographers, but from the sky. So, thanks to Gimpel, readers of the magazine had a stunning view of the pioneers of aviation.

From this date, the photographer started to exploit this bird's eye view in order to set himself apart from other reporters and to seduce the press.

[update: found some via fantomatik]

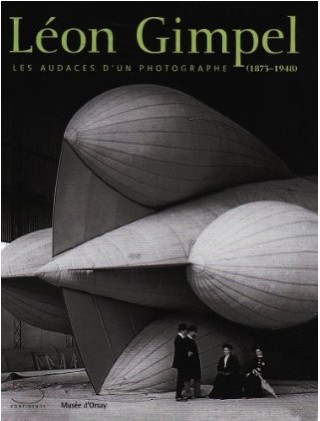

Fortunately, there's a catalogue. Unfortunately, it doesn't look to be readily available in the US. Judging from the cover, though, I could probably ask Ricci Albenda to lend me his copy.

Léon Gimpel (1873-1948), Les audaces d'un photographe [musee-dorsay.fr via ck/ck, the equally awesome tumblr of Swedish designer Claes Källarsson, thanks Erik]

More Gimpel images: La guerre des Ballons de Leon Gimpel [fantomatik]

January 30, 2011

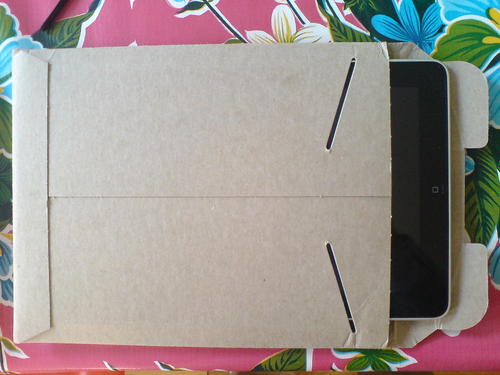

Yesterday I was looking around for something to take my iPad on the train, and I saw that it fits perfectly in the thick cardboard envelope my Cabinet magazine came in.

I love the idea of a found, cheap, repurposed iPad case that provides a decent amount of protection. But I also wonder if this could work even better in a slightly more advanced material. Maybe Kickstart a development plan, test out some small batches in various Kevlars and polycarbonates and whatnot.

Or maybe low-profile, recyclable cardboard is where it's at. You could subscribe, and they'd send you a new iPad case when they start to wear out, maybe every quarter. And maybe entice you with a free magazine inside.

$31/100ct is a pretty good price for 9x11.5 inch kraft mailers. [esupplystore.com]

Amazon's got 100ct for $49, which is alright. [amazon]

January 29, 2011

After dropping in on the National Portrait Gallery's daylong symposium [it's still going on, in fact] connected to Hide/Seek just now, and though I only saw two presentations, whoa--I feel like a cigarette.

Jonathan Katz, co-curator of Hide/Seek, titled his paper: The Sexuality of Abstraction: Agnes Martin, and he rather amazingly addressed Martin's embrace of the substantive stasis of Zen as an alternative to the more prevalent and problematic model of the closet for not addressing her lesbianism. Which she at once did and did not do in some of her formative early New York work, and which she very much did not do when she wrote and talked so extensively about her work.

One particular work, a 1961 drawing titled Cow, for example, has been traced to an illustration in her D.T. Suzuki book, where an oxherder and an ox contemplate a circle in a square. And then Katz read a quote from the artist's statements from one of Martin first shows in NYC, in which she quoted a famously, directly erotic Gertrude Stein poem--but stopped right before the hot parts. And--who knew? not I--he read some other famous-among-lesbians poem where Stein rather rhythmically builds up, and up, and up, to the moment of climax--which is symbolized by a cow. Suffice it to say, Katz's phrase, "Stein's orgasmic cows" is now right next to Gorky's "cosmic vulva" in the modernist discourse. [Holy smokes, I just Googled "cosmic vulva" and Gorky and came up empty. Have I not told that story? My apologies. Let me rest up, and then I'll get right back into it. I'm not 19 anymore, you know.]

Anyway, hot on the heels of Martin's Zen sex koans, Dominic Johnson presented work from his forthcoming book on Jack Smith's 1963 film Flaming Creatures and what he calls the "burden of disgust."

I'd heard the general story of the obscenity controversy around Flaming Creatures, prints of which were seized by police, and became the basis for several criminal obscenity cases and appeals. But I had no idea that when Lyndon Johnson was nominating Abe Fortas to be Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in 1968, conservative senators, led by Strom Thurmond, raised Fortas's criticism of the Flaming Creatures convictions as evidence of liberalism's inherent perversity.

And that to make his point--are you sitting down? You really should be sitting down--Thurmond organized a Senate screening of Flaming Creatures during the Fortas hearings. And he sandwiched Smith's avant-garde piece between a random strip-tease film, and a couple of run-of-the-mill straight hardcore porn flicks. At the Senate. Charles Keating apparently told Newsweek that the film was so disgusting, it didn't even arouse him. This he told to Newsweek.

Sometimes it feels like you think you know the world you're living in, and sometimes, wow, you just don't.

WOW, HAS IT BEEN TWO YEARS? UPDATE I was searching to see about Johnson's Jack Smith book, and I found the videos of the "Hide/Seek" symposium presentations, so I added them here. Good times.

Meanwhile, the book, Glorious Catastrophe: Jack Smith, performance and visual culture, was released last summer. I haven't seen it, or any reviews of it, which seems unusual.

January 29, 2011

So much history-making postwar art missing, so little time!

The Pebble Beach Art Heist had gone cold for a while, but now, thanks to a new website ["made on a Mac"!] it is flaming back to life. And for the first time, we get to see a photo of what is surely one of the Most Important Missing Paintings In The World: the Pebble Beach Pollock.

January 28, 2011

Maybe it was me looking for Tacita Dean's Sound Mirrors that brought me there, but David Williams' 2009 post at Skywritings about Dean, Derek Jarman, Dungeness, gardens, Tehching Hsieh is pretty wonderful:

Everything here has been found, salvaged, re-cycled from this sea-edge place, and is both displaced and quite at home. A manifest testament to qualities of patience, economy, playful invention and a quiet contemplative thusness. For the garden stages a deep acceptance of being here in all modesty and attentiveness. Taking time to make space. Slow time, still moves. A bricoleur Picasso meets the Zen garden.Still looking for that Sound Mirrors piece. I suppose I should just go to the gallery.Jarman bought the house in 1986 for £750; he was scouting for bluebells with Tilda Swinton and Keith Collins for a film shoot. He called it his 'paradise at the fifth quarter', a place where he could walk in the 'Gethsemane and Eden' of his garden and 'hold the hands of dead friends' (Garden).

(Once, when my mother was very ill in hospital, she told me that her mother had just visited her, what a shame I'd missed her. She had knocked on the window, told her that she should 'come out into the garden', it was good out there, and it was time. Her mother had died more than ten years beforehand).

In fact, skywritings is good all over. [sky-writings.blogspot.com]

January 28, 2011

I've been kind of busy, and I didn't want to get fingerprints all over the signed edition, and my few original issues are in storage somewhere, so I'm really only now getting a look at Primary Information's beautiful facsimile copy of Avalanche magazine. I'm on page nine and I'm tempted to blog my way through the whole thing. Just so much going on. Here's a taste from Avalanche No. 1, Fall 1970, from Rumbles, the front-of-the-book, which reads like the alumni news section of Conceptual Art University:

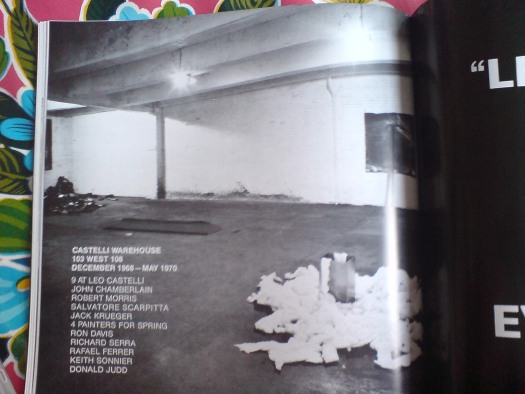

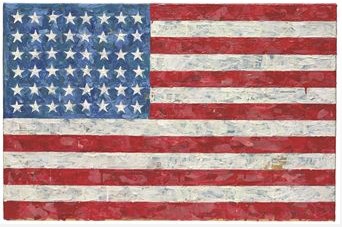

James Turrell, 27-year-old LA sculptor, who has not formally exhibited since his only one-man show of projected light works organized by John Coplans at the Pasadena Art Museum in 1967...In April 1969, Turrell and Sam Francis made a sky drawing using two World War I biplanes, radio-controlled from the ground, as part of Easter Sunday in Brookside Park organized by Oliver Andrews, Judy Gerowitz [!] and Lloyd Hamrol, who participated with elemental outdoor projects...Ooh, an ad for 9 at Leo Castelli, the seminal show Robert Morris curated at Castelli Warehouse--which was not the Castelli Warehouse from which Jasper Johns' Short Circuit flag painting was taken, but still....

Work began this summer on Paolo Soleri's Arosanti, a rural housing complex for two thousand inhabitants on a seven acre site seventy miles north of Phoenix, Arizona...

...

The Museum of Conceptual Art opened on Wednesday, March 18 in San Francisco's Market Street district with a participatino piece in which buckets of paint were given to the guests to paint the walls white....MOCA's latest show, Sound Sculpture As a one night presentation of successive sound events by ten Bay Area artists, was held on April 30...Allan Fish's piece was performed by Tom Marioni. Perched atop an eight foot ladder, he pissed into a galvanized washtub. As the tub filled, the sound dropped in pitch. He was followed by Terry Fox, who scraped a shovel across the linoleum floor and vibrated a thin plexiglas sheet very fast. Jim McCready paraded four girls wearing shiny nylons down a 3x9' long rug. As they rubbed their thighs together a swishing sound was heard....

...

Andy Warhol...now has financial backing for his first Hollywood-based film, Specimen Days, the story of Walt Whitman's experiences as a Civil War male nurse. With shooting set to begin around mid-October in New Orleans, the regulars are ready but the lead is still to be cast. Allen Ginsberg, Mick Jagger, and John Lennon have all turned it down.

...

After his recent New York visit, LA based artist Terry O'Shea has returned to California and plans to execute a large-scale ecological project involving fast-growing plants.

...

The Japanese police detained San Francisco artist Paul Cotton for wearing a pink bunny costume to the Pepsi Pavilion at Osaka's World's Fair. John Perreault gave Marjorie Strider his old Iowa summer teaching job so that he could concentrate on his first book for Abrams, Andy Warhol

Ooh, a big picture of the misty Pepsi Pavilion surrounded by moving sculptures in the ad for Robert Breer's show at Galeria Bonino? Where is Robert Breer these days, btw? That's not a rhetorical question, either.

The trade edition of Avalanche is under $100 at Amazon. The first nine pages, at least, are highly recommended.

January 27, 2011

John Powers just retweeted it now in parts, and he included it in his epic Star Wars Modern piece at Triple Canopy last year, but this quote from "American Painting During the Cold War," Max Kozloff's 1973 Artforum article, is worth repeating again and again:

It signifies a new sophistication in bureaucratic circles that even dense and technical work of the intelligentsia, as long as it was self-censoring in its professional detachment from values, could be used ambassadorially as a commodity in the struggle for American dominance.Reprinted in Artforum, Kozloff's piece was originally the introduction to the catalogue for Twenty-Five Years of American Painting, 1948-1973, James Demetrion's 1973 exhibition at the Des Moines Art Center.

Demetrion would later become the director of the Smithsonian's Hirshhorn Museum.

January 27, 2011

In reviewing Johan Grimonperez' 1997 film, Dial H.I.S.T.O.R.Y., which was exhibited at Deitch, Ronald Jones underscores artists' failure to, well, to matter very much in contemporary culture. And he reminded me of this, which I had completely forgotten:

Paul Goldberger's piece in the New Yorker on Frank Gehry's Bilbao museum made an important claim: 'The politics of the Guggenheim Bilbao', Goldberger writes, 'are evident in a single word, "MUSEOA", that is plastered onto the building's facade in enormous letters'. Goldberger's point is that, 'museoa' is not Spanish but means 'museum' in the language of the Basques. We take from the Goldberger essay that a collision between art and politics was inevitable in Bilbao. As a part of the Bilbao Pageantry Jeff Koons' well known Puppy (1992), the floral sculpture that made its magnificent debut in Kassel a few years ago, was to be erected and brought to life with local flowers. Languidly watching workmen hang pots of flowers over the gigantic pup, the police ran a casual check on the license plate of the truck which had been used to deliver the flowers. The truck and plate did not belong together and that's how the terrorists were found out. When the police began nosing around they discovered that the 'gardeners' were arming the adorable puppy with flower pots containing remote-controlled grenades. After the shoot out, in which one policeman was killed, the florist-bombers, members of the Basque group ETA, escaped. Several have since been arrested.[via frieze]

January 26, 2011

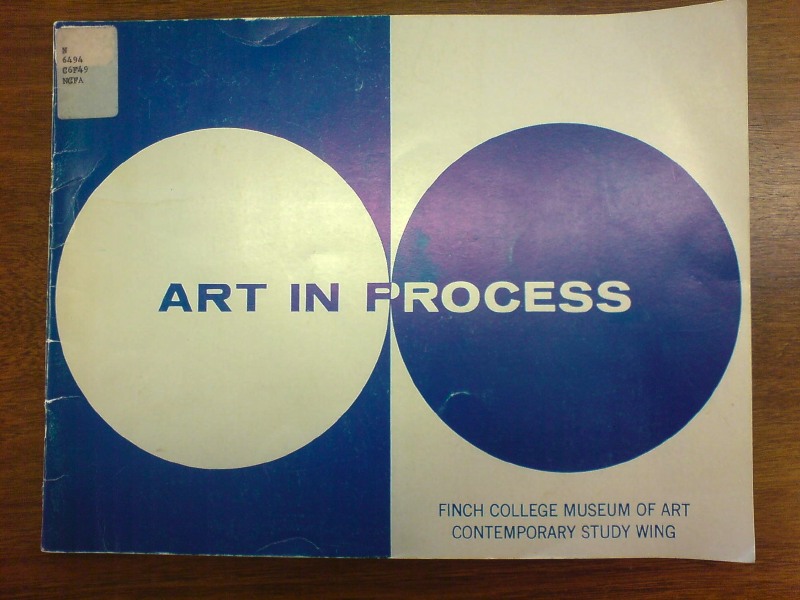

Now we're getting somewhere, even if it's only to the library.

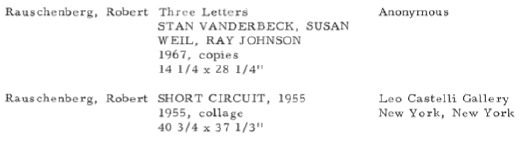

Since the Finch College Museum was originally [and wrongly] fingered as the site of the theft of Johns' Flag from Rauschenberg's Short Circuit, I've been looking for months to buy a copy of the 1967 exhibition catalogue for Art In Process: The Visual Development of a Collage. Well, not so easy. Increasingly desperate and frustrated with the failings of the Internet Age, I decided check the library. Turns out the Smithsonian's Museum of American Art library, right next door to the Archive of American Art, had a copy. Took like two minutes.

Art In Process was a series of topical, process-oriented, teaching exhibitions organized by Finch College Museum director Elayne Varian. They included sketches, models and studies to show how the artist did what he was doing. From Finch, which was on East 75th Street, the show traveled for 18 months to nine other smaller museums around the country in a tour organized by the American Federation of Arts. [Thanks to the original press release, provided by the AFA, the list of venues is below.]

I'm not the only one who had trouble finding the catalogue, though. Paul Schimmel's huge Rauschenberg Combines catalogue said the flag painting was stolen while Short Circuit was on exhibit. That's how he read the entry in Walter Hopps' 1976 retrospective catalogue, which mentioned Finch and the missing flag together.

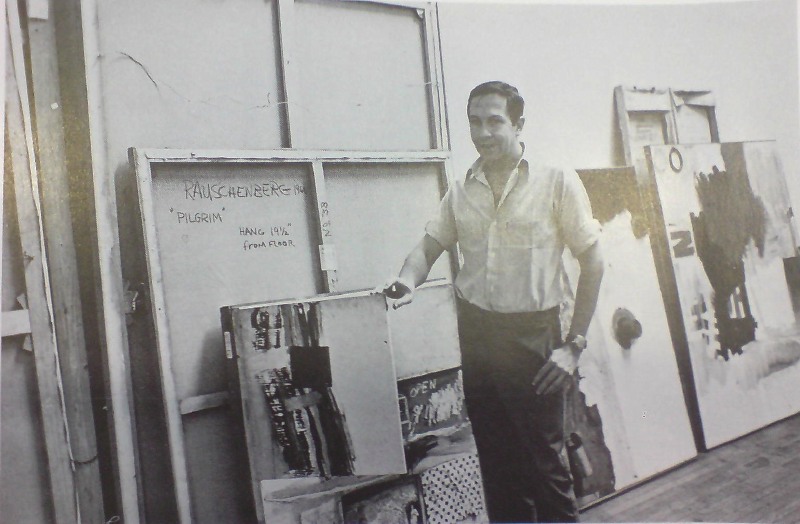

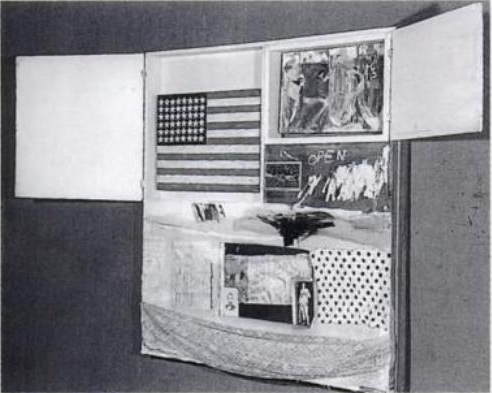

But. Check out what Rauschenberg actually said. Well first, check out that photo!

It's Bob, teasing us with what's behind Short Circuit Door No. 1. Because there is nothing:

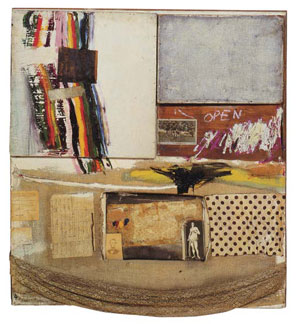

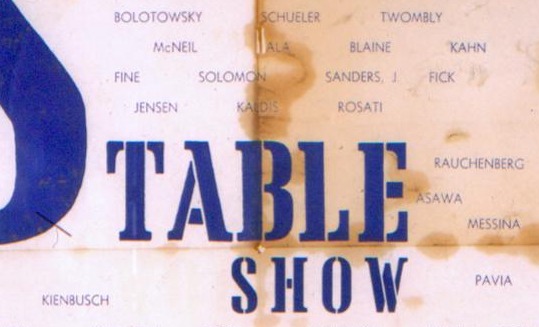

In the third Artist Show at the Stable Gallery, my collage, SHORT CIRCUIT, 1955, was motivated by the protest that there had not been any new artists invited to exhibit. Therefore, I invited four artists: Jasper Johns, Stan Vanderbeek, Sue Weil and Ray Johnson to give me works to be built into my collage. Only two paintings were ready in time to be installed into the major piece. The collage also contains the autograph of Judy Garland, and one of the first programs of a John Cage concert. Because Jasper Johns' flag for the collage was stolen, Elaine Sturtevant is painting an original flag in the manner of Jasper Johns' to replace it. This collage is a documentation of a particular event at a particular time and is still being affected. It is a double document.Give me. Built into. My collage. Only two. Is painting. These are the phrases that jump out at me.

Not only was Art In Process the first acknowledgment of the removal of Johns' flag, almost two years after it happened, it was the first public exhibition for Short Circuit since Alan Solomon's group show at Cornell in 1958. After being the subject of some kind of joint, post-breakup negation agreement between Johns and Rauschenberg, where the combine was not exhibited, published, or even, it seems, discussed, Short Circuit went on a cross-country tour, without the flag, and with the doors nailed shut.

I thought I'd be all Errol Morris about it and date the photograph from the other works in the background, but it doesn't really help: Pilgrim (1960), on the left without its chair; Johanson's Painting (1961), in the middle, with the tin cans, was in Ileana Sonnabend's collection; the other combine painting with the N or Z element, I haven't found yet. [Any ideas? Send'em in!] That watch Bob's wearing looks like the one in the Avedon photo on the cover of Schimmel's Combines, which was taken in 1960. But I'll say Bob's face looks a few years older, at least five, if not seven.

So this photo was probably not, then, taken before 1965. And Johns' flag painting is probably not, then, behind that door. And Bob is probably not, then, toying with the terms of the no-repro "solution" he and Johns devised for this double document.

Other things: Sturtevant's flag sounds like it's in process. Unless that "Sturtevant is painting an original flag" is the same tense as "I am making an animated musical," somewhere well short of "she's delivering it this week," and closer to "well, we've talked about it." Because though a Sturtevant flag sighting was reported in 1971, There were no photos of Short Circuit for Hopps to publish in 1976, and Rauschenberg talking of painting a flag himself because he "need(s) the therapy." And when David Shapiro and Hirshhorn curator Cynthia McCabe scouted the combine out in 1985, they had a "very sad experience" looking at the work, in a "state of real disrepair," with mentions only of the absence of Johns' flag and none of Sturtevant.

No mention of Ray Johnson's inclusion. How classic for Johnson's own collage that it gets subsumed so totally as Rauschenberg's. It's as if only the paintings can hold their own against the combine's powers of assimilation. Resistance is futile. I guess that's the real question here.

For Johnson, though, it's probably the giddy answer. He was also included in Art in Process on his own, so don't sweat for him. If anything, that's how he wanted it. Here's writer/artist/curator Sebastian Matthews:

Over the next decade, Johnson made a series of anti-rectangle collages. It wasn't long before Johnson was mailing out collage fragments "for others to use or send on," letting go authorship (at least in part) and allowing the work to be formed by increasingly random collaborations. No coincidence, then, that Johnson made this creative leap during his transition from Black Mountain to New York City while hanging out with his BMC buddies.That's from Matthews' proposal/thesis for an awesome-sounding show, BMC to NYC: The Tutelary Years of Ray Johnson, which he organized last fall at Black Mountain College + Arts Center in Asheville, NC. Sounds like Short Circuit was as formative and in harmony with Johnson's emerging practice as it was problematic for Johns'. That may be too simplistic, but it's way past time to take a closer look at the rest of Short Circuit, too.

The dimensions: The Finch catalogue lists the dimensions for Short Circuit as 48 x 48 inches, which, since Bob was not seven feet tall in that picture, is obviously wrong.

Another reason for checking the Finch catalogue was to see whether Short Circuit was still owned by Rauschenberg or, if it was still, as Michael Crichton reported, in Leo Castelli's collection. And it doesn't say. But the press release might. Artists, like Al Hansen, were listed as lenders for some works in Art In Process, but works were credited to the artists' dealers. Short Circuit was apparently lent not by Rauschenberg, but by Leo Castelli Gallery. The mounted photocopies of letters to Ray Johnson, Stan Vanderbeck [sic] and Susan Weil, meanwhile, were lent "anonymously." Wait, the what?

January 24, 2011

While I'm obviously no David Hockney, after a year or so, I see a Brushes trend emerging: people sitting in front of me.

On the most recent one, I decided to pare it down.

From the width of the seat, you can see I'm able to fly coach.

Now that everyone's a courtroom sketch artist, I wonder on the state of iPad-based reporting. Is anyone not named Steve Mumford sketch-reporting from a war zone? Is anyone not named Ruben Toledo doing front-row sketches from the fashion shows? [If so, would they acknowledge they're not actually in the front row by including the heads of the people sitting in front of them?]

Or are both of those scenes too fast? Does Brushes require an element of boredom, or at least waiting, downtime, to make it work as a live medium? Or maybe you draw the audience while Marc Jacobs makes everybody wait for Rihanna or whoever to arrive?

January 23, 2011

In 2002, as I was still trying on various kinds of public writing, I tried to capture the transformative experience of listening to--no, experience is the better word--On Kawara's One Million Years.

That post was even titled like a screenplay: "Setting: Fredericianum, Documenta II, Kassel."

image via mightymac

In April 2004, South London Gallery staged a week-long, round-the-clock marathon reading of One Million Years in Trafalgar Square. Many passersby unfavorably compared Kawara's volunteer readers in their glass box to David Blaine, who had, just a few months before, spent 40 highly publicized days in a plexiglass cube suspended from a crane next to the Thames.

In 2009, when David Zwirner staged a reading/recording of One Million Years, Brian Sholis wrote touchingly and with great acuity about the experience of reading the years 79,936 AD - 80,495 AD with his then-fiancee.

And yet only just now, somewhere between finding Jerry Saltz's characteristically gossipy, angst-ridden account of reading in the same show, and watching this comical YouTube video of Martin C. de Waal, a Dutch club kid/stylist/Orlan-style conceptual self-portraitist and his dance remix singing partner Marina Prins [!] getting all dolled up for their reading on the open platform at the Stedelijk--the one we'd been standing on a few weeks ago--do I realize the powerful performative essence of Kawara's piece. And with less than a hundred of an anticipated 2,700+ CDs burned, it's barely even begun.

The effect of living in a post-Marina world, I suppose

January 22, 2011

If you can see the full text of "On Collaboration In Art," David Shapiro's conversation with John Cage, published in the Autumn 1985 issue, (No. 10) of Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics, perhaps you can tell me if it does, in fact, discuss Rauschenberg and Johns' work on Short Circuit as the web-based search appears to indicate?

Thanks!

On Collaboration in Art: A Conversation with David Shapiro

David Shapiro and John Cage

RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics

No. 10 (Autumn, 1985), pp. 103-116 [jstor.org]

update: Thanks to greg.org readers B and G, we know the answer is yes, yes it does, and wow, very interesting. Here is Shapiro asking his friend Cage about Black Mountain and how he perceives collaboration:

DS: So collaboration also implied simultaneity?I was going to add italics for the rather salient language these folks were using, but well, where to stop?JC: That's all it really means to me.

DS: Two things happening at the same time.

JC: That is their relationship.

DS: Bob Rauschenberg often seems optimistic, inclusive, as if he's marrying the whole world, like permitting Jasper Johns's flag to be inside a larger sculpture. It seems like a sign of generosity. He sometimes seems generous in his collaborative spirit. You don't think of it as necessarily emotionally generous to collaborate? Is it not a sign of charity?

JC: No. It's a willingness to have your work experienced at the same time other work is experienced. I'm being careful not to use the expression "willingness to come together," because there's no coming together really. It's two different different things that if they do come together at all, they come together where Marcel [Duchamp] said a work of art was completed, in the observer. But the two people who are collaborating are not observers until they can be. Then, when they are observers, they're no longer collaborators.

Hirshhorn curator Cynthia McCabe was there, too, and Shapiro's wife, the architect Lindsay Stamm Shapiro. McCabe really wanted Short Circuit for the Hirshhorn's 1985 exhibition, "Artistic Collaboration in the Twentieth Century":

CM: We just had a very sad experience looking at the Rauschenberg Short Circuit that Jasper had done with him and Susan Weill [sic]. It's now in a state of real disrepair. It's so important for this exhibition.LS: Where is it?

DS: It's in Rauschenberg's studio, but Johns's flag had been stolen at the place. It had been shown at Finch College. It is like a wing to an altarpiece, and inside was a Susan Weill. I'm sure you've seen it.

CM: There was a little sticker in there, I'm trying to think of which was the work, it says "Cage."

DS: Yes, it has a little collage mentioning a performance that you had done. I think with David Tudor. When David Tudor does chord clusters in the record indeterminacies, was that collaborative or completely mapped out by you, so he's the performer?

JC: He's playing the Solo for Piano from the Concert for Piano and Orchestra.

January 22, 2011

A little Saturday stenography. Alan Solomon wrote "The New Art," a catalogue essay for "The Popular Image," one of the first museum exhibitions of Pop Art, organized by Alice Denney in the spring of 1963 at the fledgling Washington Gallery of Modern Art. [Solomon would go on to restage the show in the ICA in London that fall, sort of obscuring or usurping Denney's and the WGMA's position in the history of Pop.]

Anyway, Solomon, who had just left Cornell to establish the Jewish Museum's contemporary program, where he gave Rauschenberg his first retrospective, and who would soon be the commissioner at the Venice Biennale where Rauschenberg would be the first American to win the International Painting Prize, discussed both Rauschenberg and Johns, along with Allan Kaprow, as key influences on the nascent Pop Artists. Because no one else seems to have put it online, here are some extended excerpts from Solomon's essay:

The point of view of the new artists depends on two basic ideas which were transmitted to them by a pair of older (in a stylistic sense) members of the group, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. A statement by Rauschenberg which has by now become quite familiar implicitly contains the first of these ideas:Painting relates to both art and life. Neither can be made. (I try to act in the gap between the two.)Rauschenberg, along with the sculptor Richard Stankiewicz, was one of the first artists of this generation to take up again ideas which had originated fifty yeras earlier int he objects made or "found" by Picasso, Duchamp, and various members of the Dada group. Raschenberg's statement, however, suggests a much more acute consciousness of the possibility of breaking down the distinction between the artist and his life on the one hand, and the thing made on the other.

January 22, 2011

So I thought I'd check Jasper Johns' bibliography to see if there was a review for Alan Solomon's group exhibition at Cornell, which included Short Circuit.

There was not, but after seeing the first entry for 1958, from Johns' hometown paper, I really don't mind:

"Allendale Artist Paints What He Likes-Happens to Like Flags!" Chronicle (Augusta, Ga.), April 6, 1958. Discusses March 31, 1958 issue of Newsweek.

January 21, 2011

Rather sensibly, IBM tapped Errol Morris to create films commemorating the company's 100th anniversary. Even when a guy delivers slightly underwhelming lines like, "We changed the way the world shops," this one, They Were There, is pretty awesome.

My dad worked for IBM for decades, long enough for me to have a bias for white dress shirts ingrained into my psyche. And I did interview Errol Morris that one time.

And while I can understand why it's not in there, I do kind of wish the company would, when celebrating its history, acknowledge the longstanding, critical role IBM, its technology, and its German subsidiary played in the Holocaust. Because they were there. And that's certainly more important than changing the way the world shops.

IBM Centennial Film: They Were There - People who changed the way the world works [youtube via daringfireball]

January 21, 2011

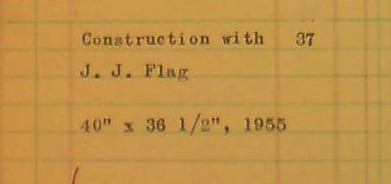

tiny detail of a Robert Rauschenberg registry, dated 1957-9, which I can't reproduce in full because of the terms of access to the Leo Castelli Gallery Archive at the Archives of American Art

Another day back in the Leo Castelli Gallery papers at the Smithsonian's Archives of American Art, and barely further along in my project to piece together the surprisingly complex history of Robert Rauschenberg's Short Circuit.

After finding Castelli's insurance claim for the "loss" of the Jasper Johns flag painting which was originally included in Short Circuit--a claim which makes absolutely no mention of Short Circuit itself or Rauschenberg--and reading Michael Crichton's first published account of what happened, I wanted to see if there was any record of Short Circuit entering Castelli's collection.

There was not.

The folks at the AAA who'd processed Castelli's archive had already warned me that there was remarkably little personal material, and little relating to Castelli's own collection. Nevertheless, there were plenty of traces of Leo's own holdings scattered throughout the files; when Rauschenberg's Bed was discussed, for example, Castelli's ownership of it was at least mentioned.

What I came to see, though, is that especially when compared with other combine paintings from the 1950s, or, other works in Castelli's and Rauschenberg's collections, Short Circuit was almost completely absent from the ever-increasing stream of notes, discussion, and paperwork related to the artist's career.

It'd be weird to lay out all the places that Short Circuit wasn't, but I'll give two examples: until the 1965 insurance claim, it never showed up in the photo reproduction orders the gallery sent to Rudy Burckhardt, who apparently shot all Rauschenberg's [and other Castelli artists'] work at the time. In early 1967, when the gallery was negotiating with the British writer Andrew Forge to publish Rauschenberg's first monograph, Short Circuit was not included in any otherwise comprehensive-seeming works lists or photo lists he received.

I have to think this negation-by-withdrawal is linked to Rauschenberg's breakup with Johns, and to what Johns referred to in 1962 as the "solution of differences of opinion between him and me over commercial and aesthetic values relating to that work." So long as had Johns' flag painting in it, Rauschenberg was to keep the work out of public circulation.

In fact, the only archive mention of Short Circuit at all before Rauschenberg's 1976 Walter Hopps retrospective, is in an early artist's registry. The looseleaf, ledger paper list is dated 1957-59, when Rauschenberg and Johns were together and both having groundbreaking first solo shows at Castelli [in 1958, Johns in January, and Rauschenberg in March].

And technically, it wasn't even Short Circuit; it was listed as "Construction with J.J. Flag," with the dimensions and date, "40 x 36 1/2, 1955."

There's alo a handwritten notation that the work had been exhibited at Cornell University in the spring of 1958. That would be the second showing Johns had referred to in 1962. [The first, the 1955 Stable Gallery show for which it was created, is not mentioned.] The idea that Short Circuit--a work which merged the two artists' signature innovations--was exhibited immediately after their controversial, back-to-back, solo shows would seem like big news. But no. Paul Schimmel's 2005 Combines catalogue only lists the "group exhibition" in a footnote, and I haven't found any other reference to the show online. In 1958, the director of the Cornell Museum would have been the critic/professor Alan Solomon, who was tight with all those Poppy guys. [He'd go on to curate definitional Pop Art shows in 1962.] I've contacted Cornell; we'll see if they have anything on the show.

If there was a "difference of opinion" about publicly displaying Short Circuit, I think we can assume that Johns did not want it shown, and Rauschenberg did. Because soon after the flag painting was removed, Rauschenberg put the combine into Elayne Varian's traveling collage exhibition at Finch College Museum--with the doors nailed shut.

It's funny, all this time I've been poking around this piece, I've thought of it in terms of "getting the Johns back." But when you think about it, the one who got his work back in this caper is Rauschenberg.

UPDATE: Whoa, I just noticed that the dimension mentioned above--40 x 36 1/2"--don't match up at all with those given in Hopps's 1976 catalogue: 49 3/4 x 46 1/2. What up? Is "Construction with J.J. Flag" NOT Short Circuit after all? It is an error, another missing flag/combine combo, or an upending of the original Stable Gallery story? If the Johns flag is 17" or so, there is no way that piece above is 50", or even 46". Gagosian lists the dimensions as 40 3/4 x 37 1/2", which is close enough for me. No sweat, Hopps & co just had bad info.

January 19, 2011

I tried searching the 150,000 million images in the ETH Bibliothek photo archive, too, but I sure didn't come up with one of these:

One thing's for sure, though: if I were ever to show some videos on little screens, I will be definitely be putting my iPads or whatever in some of these things. Just awesome.

ETH Bibliothek Bildarkiv [ba-epics.ethz.ch via anambitiousprojectcollapsing]

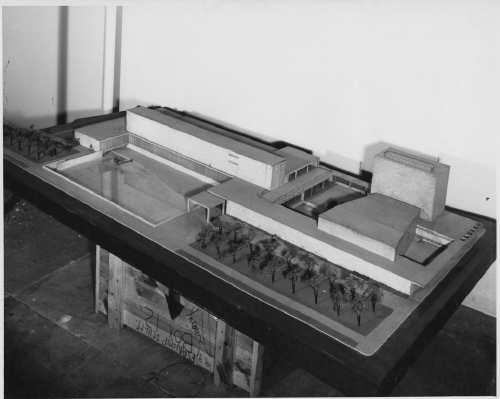

Huh, so I'm poking around online for info on the Saarinens' unrealized design for a Smithsonian Gallery of Art [above is a SI photo of the model, built in 1939 by Ray and Charles Eames, of all people, perched atop, of all things, the crate for a Paul Manship sculpture. And I'm thinking how it's too bad that WWII happened, because otherwise we'd have a sweet modernist art museum on the Mall--hah, as if.]

[According to the Smithsonian American Art Museum's own history, the building never had a chance. It wasn't Congressional budget cuts or wartime reprioritizations that killed the project--it was the rejection of the modernist design by the Smithsonian Regents themselves, and by the Commission on Fine Arts--because it was modernist.]

[Charles Moore, an influential retired Chairman of the CFA called its "sheer ugliness...an epitome of the chaos of the Nazi art of today." Which, yow. The Commission which rejected it included sculptors Paul Manship and Mahonri Young, a grandson of Brigham Young.]

But that's not the point. Point is, a quote stuck out from the book as being both timely and relevant. It's from Holger Cahill, head of the WPA's Federal Art Project [and holy smokes, Mr. Dorothy Miller], which organized artists to make work for public buildings and spaces. He believed art and artists and the public all benefit by "a sense of an active participation in the life and thought and movement of their own time."

I haven't found the original publication info, but since the source of that 1936 quote only appears on Google as a writing sample for an English 201 course, I put the whole thing after the jump. Take a read and try to imagine it as not a politicized, partisanized view of contemporary art:

January 17, 2011

You know what, it's been too long since we had a good, old-fashioned photomuralin' around these parts.

And one that combines a bit of Google Maps-ready, roof-as-facade architecture? And camo? Even better.

I only go to the Museum of the City of New York for their gala, and I'm the loser for it: because I missed "Shaping the Future," curator Donald Albrecht's Fall 2009 exhibition of Eero Saarinen.

The show included the 1939 model for the unrealized Smithsonian Gallery of Art, which he designed with his father Eliel, and which would have sat across the Mall from John Russell Pope's just-finished neo-classical National Gallery.

But it also included some sweet, giant photos, as the NY Times' slideshow shows. Check out the big CBS-eye view of Saarinen's model for Black Rock:

The Google Maps reality is, alas, not so clean. Saarinen's CBS HQ has the usual skyscraper cruft on the roof.

But fortunately, it's right across the street from MoMA, where landscape architect Ken Smith's 2005 Roof Garden is clearly visible. As the American Society of Landscape Architects noted when it gave Smith an award in 2009, the design is rooted in historic concepts of camouflage and the abstracted simulation of natural forms.

And speaking of simulation, check out this giant color photomural from the MCNY exhibition, which almost makes you feel like you're right there in the living room of Saarinen's 1953-7 Miller House [which the family recently donated to the Indianapolis Museum of Art].

Weird, the angle of the Times photo really exaggerates the sense of perspectival space in ways that a straight-on shot like the one arthag took does not.

Review | Eero Saarinen: Shaping the Future [nytimes, for full-size images: Librado Romero/NYT]

January 16, 2011

Maybe it's the CSI-ification of everything, but as I dig through archives and piece together timelines, and interview people--oh, I haven't really mentioned the interviews, have I?--while trying to track down the story of Robert Rauschenberg's Short Circuit and its little, missing, Jasper Johns Flag, I sometimes feel like a character in a John Grisham novel.

Maybe it's the CSI-ification of everything, but as I dig through archives and piece together timelines, and interview people--oh, I haven't really mentioned the interviews, have I?--while trying to track down the story of Robert Rauschenberg's Short Circuit and its little, missing, Jasper Johns Flag, I sometimes feel like a character in a John Grisham novel.

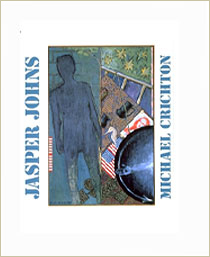

Which is funny, because the greatest book I've found on Jasper Johns so far is by Michael Crichton. Seriously, with his 1977 book, Jasper Johns, created for the artist's mid-career retrospective at the Whitney, Crichton defined the exhibition-catalogue-as-pageturner genre.

After my most recent visit to the Smithsonian's Archives of American Art last week, I had a few minutes to spare, so I ducked into the Museum of American Art Library across the hall to flip through Crichton's catalogue and to see if there was any mention of Short Circuit in the supposedly exhaustive catalogue for Anthony d'Offay's 1996 show of Johns' Flags. [There wasn't, and though it had a couple of good ideas, David Sylvester's essay was uncharacteristically uninteresting.]

Well, flipping through Crichton's book was riveting. I could only read a few pages, but it felt like a mystery, a suspenseful, personal investigation into the artist, his thinking, his process, and his work. It was chock full of quotes from people who know and work with Johns, evidence of Crichtons' conversations and interrogations. I wanted to read every one. And it was only the recurring image of my kid waiting, alone, on the curb outside her pre-school, wondering why her daddy had forgotten her, that forced me to stop. It's an intense, infectious curiosity that I admit I haven't really felt towards Johns' work before.

In the course of this recent, somewhat intense look at Early Johns, I've been struck and sometimes a bit put off by the artist's apparent/reported hermeticism, his opaqueness. Not that I want art spoon-fed to me, or served up like some all-I-can-consume Baselian buffet. But if Johns wants to be obscure, closed, personal, private--yeah, I'll go with closeted--then fine. Far be it from me to pry. And far be it from me to take advantage of that reticence by projecting my own theories and interests and speculations on the artist and his work, as a great deal of critical writing about Johns seems to do.

But while he addresses and acknowledges Johns' seemingly impenetrable work and persona, Crichton also quotes a close friend saying something like, no, "Jasper wants to be understood." [I'll look it up later when my copy of the catalogue arrives.]

the very flaggish, hinged In Memory of My Feelings - Frank O'Hara, 1961, Art Inst. of Chi., via NPG

And that, coupled with the remarks from the curators of "Hide/Seek" that it was the first time Johns has ever allowed his work to be seen in a queer context [that link it to Michael Maizels' discussion of the show], makes me feel that this longer, closer look at this painting--these paintings--is not just alright, but right. And that Johns would agree.

Anyway, the point is, buy this book. No, no, the point is, Johns rewards close, intense looking, and Short Circuit, both in its original state and throughout its fraught, altered history, feels like a key touchpoint in the works, lives, and careers of these artists. And it turns out that no one has gotten its story totally straight yet, not even Michael Crichton.

There is a note in Crichton's Johns story that begins:

As a curious historical incident, a Johns painting was seen at the Stable Gallery in 1956, as part o a Rauschenberg painting.Actually it was 1955. But then there's this bombshell:

Leo Castelli later acquired the Rauschenberg with the two doors. He kept the painting in his warehouse. One day he examined the painting and dsicovered that the Johns flag had been stolen.Wait, what?? Castelli bought Short Circuit? So it was not, after all, in Rauschenberg's personal collection his whole life after all. And I only find this out after I leave the Castelli Archive. I wasn't even looking for this kind of stuff. While it explains what Short Circuit was doing in Castelli's warehouse, it doesn't explain when Bob sold it, or why Leo bought it. Or why or when Bob got it back.

The artist Charles Yoder told me last month that Short Circuit was in Bob's collection--and had Sturtevant's replacement Johns Flag when he went to work for Bob in 1971. [Though the first published mention of Sturtevant I can find is still the Smithsonian's 1976 catalogue, which ended up using Rudy Burckhardt's original, Johns-era photo.] I guess I'll have to get back to the Archive and look for Castelli's own collection records. And his correspondence with Bob. And then look for the 1967-8 Finch College Collage checklist and/or catalogue, to see who was listed as the owner of Short Circuit, which was, remember, still described as containing a Johns Flag behind its nailed-shut doors.]

So this means that sometime between--well, we really don't know when it was, just sometime before June 6, 1965--Castelli bought Short Circuit. And found the Johns Flag missing. But Crichton's not through. "Castelli recalls a final incident in the story," he writes:

Years later, a dealer--we do not need to say who--came to me and said, "Someone has brought me this Johns painting and I don't kno wit, and I wondered if you could tell me about it, the date and so on." I knew immediately what it was; it was the stolen painting. I said, "The painting has been stolen and I would like to keep it right here. I don't want it to leave my gallery." But this person said he had promised the person he got it from, and he didn't feel he could leave it with me, and he said he would have to talk to the other person, and he was very insistent. So I said, "Well, all right." I never saw the painting again."Castelli recalls"! "We do not need to say who"!

Well, this saves me a trip into Calvin Tomkins' archives at MoMA; because I will bet that Crichton's footnote is the source for the secondhand version of this incident Tomkins included his 1983 Rauschenberg bio. And where Tomkins ended broadly--and obviously wrongly--with "and nobody has seen it since," Crichton nails the quote from Castelli: "I never saw the painting again."

Which puts us back to where this whole thing started. Except that I think I now know--because I have been told by people who would know--who that dealer was, and who he was presenting the painting for. And based on some interviews I've done since, I am pretty sure I'm right.

But that turns out not to be the same as figuring out when the Johns Flag went missing, or more importantly, where it went, and where it is now. And even when Crichton quotes Castelli himself as calling the painting "stolen," and I've seen it mentioned [albeit as "lost"] in an insurance report, when Castelli had the painting back in his gallery--and had chance to get it back from someone he obviously knows--he let it walk out the door again.

Michael Crichton died unexpectedly in 2008 while undergoing treatment for throat cancer. His art collection, including the Flag painting he bought directly from his friend Jasper Johns, which he considered his single most important acquisition, was auctioned last Spring at Christie's. Mike Ovitz waxes a little hagiographic, and I deeply don't get the Mark Tansey thing, but the video that Christie's produced about Crichton and his passionate, intellectual engagement with art is really pretty good.

Measuring 17.5 x 26.75 inches, Crichton's Johns Flag [above] is much smaller than the Flag which Castelli first saw in 1958 in Johns' studio, an experience he later called, "Probably the crucial event in my career as an art dealer, and... an even more crucial one for art history." It was slightly larger, though, than the Flag in Short Circuit [13.25 x 17.25 in.]. And it was painted between 1960-66, exactly the time when Short Circuit's Flag was being contested and lost--and shortly before Castelli got it back, and let it walk back out of his door. Crichton's Flag sold in May 2010 for $28.6 million.

January 14, 2011

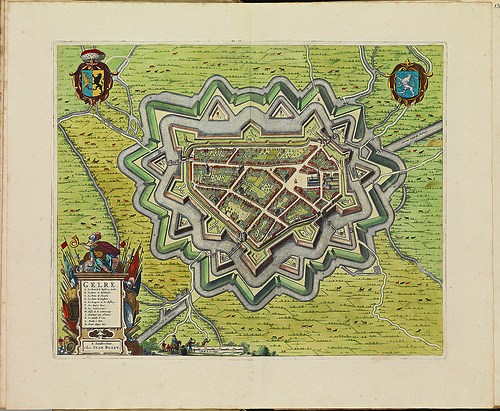

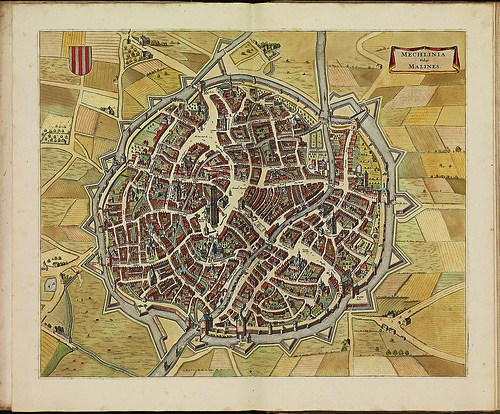

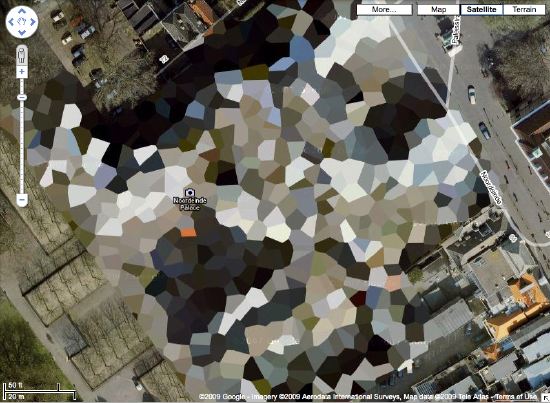

This just in from the greg.org Department of Stunningly Beautiful Digitized Maps of The Netherlands:

Bibliodyssey has some highlights from the National Library of the Netherlands' fresh upload one of the rarest and most beautiful atlases in history, mid-17th century Dutch cartographer Frederik de Wit's Stedenboek, or Book of Cities.

Who knew that the Dutch had such a long, rich, aesthetically awesome history of defense-related polygonal alterations of the urban landscape?

At least maybe now we have some idea where that crazy camo blob in Nordwijk came from:

Stedenboek [kb.nl]

Dutch City Atlas [bibliodyssey]

January 13, 2011

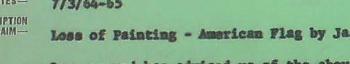

So here is where, after a few months of searching, I basically get caught up to the editors of Johns' collected writings, who noted in 1996 that Johns' Flag painting disappeared from Leo Castelli's warehouse sometime "before June 8, 1965."

After a couple of days of digging through the newly opened Castelli Gallery archives at the Archives of American Art, I found that date on the gallery's insurance claim reporting the "Loss of Painting - American Flag by Jasper Johns valued at $5000 $12,000." [the higher figure is written in by hand.]

The insurance company's memo acknowledging the claim said that "Mr. Mellors is to meet with the assured on Wednesday afternoon regarding the details of the claim."

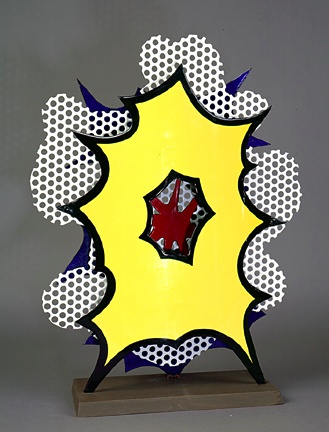

June 8th was a Tuesday, and sure enough after his visit, Mr. Mellors had more to add. A follow-up memo is titled more clearly, "Theft of Painting - 6/6/65 - "Desk Explosion 65" by Lichtenstein." Mr. Mellors, it said, "...when discussing the loss on "American Flag" by Jasper Johns was informed of the above loss by Mr. Castelli."

So what we have now is not just a "before June 8," and a "loss" [although that is still the word used in relation to the Johns], but a date: "June 6" and a "theft." And not just one work, but two.

The only other documentation I could find is a small note, "Call headquarters for 9th Precinct," "Warehouses/ 75 Cliff St/ 25 First Ave" and the name [?] "Kay Kaz."

The 9th Precinct is the East Village, which makes me think it was the First Avenue location. Kay Kaz, I have no idea, and I can't find anything online so far. But this was not Leo's handwriting, so I am assuming someone was taking this information down on the phone.

Frankly, I can't tell if I'm more Law & Order: Art Victims Unit or Columbo, but this is feeling very real to me, trying to piece together what happened, where, when, and with whom, just using a few old memos.

The 6th was a Sunday, so it seems as if someone made a weekend visit to the warehouse, found the Johns missing from Short Circuit, called the police, then called the gallery to give instructions about following up with the police. And then on Tuesday, they filed a claim for the Johns, while seeing if anything else was missing. And by Wednesday, they found a Lichtenstein gone, too.

As it turns out, both works are similarly sized: small and portable. The Johns Flag is 13 1/4 x 17 1/4 inches, and Desk Explosion is 20 x 16 x 4--wait, 4-in? It's a sculpture. An enamel-painted metal freestanding sculpture on a 4-inch deep base, made in an edition of 6:

Small....Explosion (Desk....Explosion), 1964, : image via lichtensteinfoundation.org

Either way, maybe tracking the Johns is now a matter of tracking the Lichtenstein.

So what do we know now? First, that the AAA's Castelli Archive is awesome. I could blog those boxes out for days if the photo restrictions were a little more conducive. Instead, I find them more illustrative of the way that art historical information is still transmitted: in relatively hermetic dribs and drabs.

My previous assumption that the Johns may not have been "stolen" stolen because it was never reported as such turns out to have been wrong. Well, those reports existedtl, anyway, even if the Johns wasn't exactly described as "stolen." [I was also wrong about a couple of other assumptions and speculations I made in earlier posts, which I'll get to separately and soon.] But generally, the information I'm finding does appear to have been found by at least someone, sometime, before. So I wonder what I'm doing: if all these curators and scholars have already been over this before, am I just playing art detective for my own belated educational amusement?

But questions still arise that keep me on the hook:

January 12, 2011

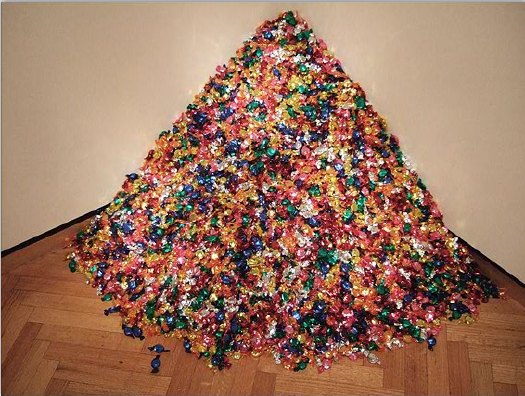

Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), 1991

RB Before I knew you I saw something... You know what I'm going to say?-Ross Bleckner interviewing Felix Gonzalez-Torres in the Spring 1995 issue of Bomb Magazine. This is about as funny as Ross gets. He really is as foolish as Felix is thoughtful. Well worth a read.FGT I dedicated a piece to Ross.

RB Exactly. I thought, this is so sweet, I want to meet him. He dedicated this thing to me and I don't even know him. (laughter) It put me in the best mood. And then someone said to me, "You idiot, why would he dedicate something to you? It's his boyfriend."

Bonus: did you know that by Fall 1994, after five solo shows and with his retrospective set to open at the Guggenheim, Felix had never had a review in the New York Times? [I just checked, and the closest was a paragraph in a cranky 1990 survey of Minimalist revival by Roberta Smith. She called his stacks "almost laughable."]

January 11, 2011

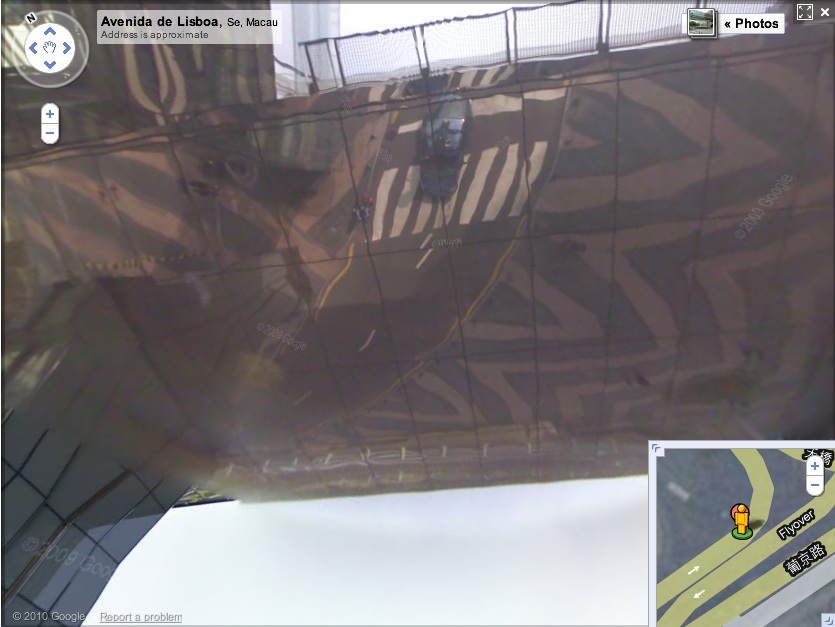

Via one of my Senior Street View Scouts John comes this eerie shot from Simple Ranger's Street View essay of Macau. [Here's the live link.]

Seriously, is that building real? Even if I wander over to look at it up close, my doubts only increase.

And frankly, looking up at the sky and seeing the Google Street View car reflected in the curved, mirrored underside of the Grand Lisboa Casino's elevated pedestrian walkway is not helping.

January 10, 2011

Compared to Germany's digital scrim effect, the Italian Google Street View opt-out regime is extraordinarily, even romantically, naturalistic.

Haha, no. It's a photo from Elmar Haardt's careful and unassuming project documenting Bondeno, a seemingly unremarkable small town in Ferrara. [via the incomparable mrs deane]

January 8, 2011

Reading through the press release for the new upscale family travel site Poshbrood.com, I was surprised and promptly filled with dread by the chance to win a "faboo Mark Cross saddlebag."

Because that means someone has brought the luxury brand back from the dead because, what, zombies are really on trend right now? Because if you have any concept of venerable or luxury or heritage or leather or gift or anything when you hear the name Mark Cross, it has literally nothing to do with anything actually happening or made this millennium. And that residual brand goodwill embedded in your brain is now the intellectual property of a roving band of scavenging garmentos and opportunistic luggage salesmen.

Which, God bless'em, credit where it's due, but also blame, awful, tacky blame.

January 5, 2011

One of the first Japanese sayings I learned was "Chiri mo tsumoreba, yama to naru," "Pile up dust and it becomes a mountain."

At his incredible blog Four Color Process, John Hilgart continues to mine the gap between comic book art and comic book printing. Looking back over his year's collection of images, often tiny details pulled from the seemingly insignificant corners and backgrounds of old comic book frames, he's come up with an excellent and expansive essay. He doesn't, but I'll call it the 4CP Manifesto:

Gone are the page, the frame, the plot, and localized contextual meaning. What remain are the color process and what are generally called the "details" of comic book art. These are the two lowest items on the totem pole of comic book value - poor reproduction and the least important, most static elements of the art itself. Our proposition is that these elements are important and aesthetically compelling.[image: Gotham Dawn, via 4CP]Who is responsible for this art? At the level of a square inch of printed comic book, no one was the creative lead. 4CP highlights the work of arbitrary collectives that merged art and commerce, intent and accident, human and machine. A proper credit for each image would include the scriptwriter, the penciller, the inker, the color designer, the paper buyer, the print production supervisor, and the serial number of the press. Credit is due to all of them, to differing and unknowable degrees, for every square inch of every old comic.

In Defense of Dots: the lost art of comic books [4cp.posterous.com, thanks city of sound for the heads up]

Previously: Four Colour Process [greg.org]

January 4, 2011

Doug Ashford ended the 2009 presentation I just posted about, "Abstraction as the onset of the real," with a slide of this beautiful painting, Untitled, 1950 (May 20) by Myron Stout.

Washburn Gallery had a sweet little early Stout show in 2007, which I'd completely forgotten about. Back when he was still writing about art, NY Times chief art critic Michael Kimmelman reviewed the show:

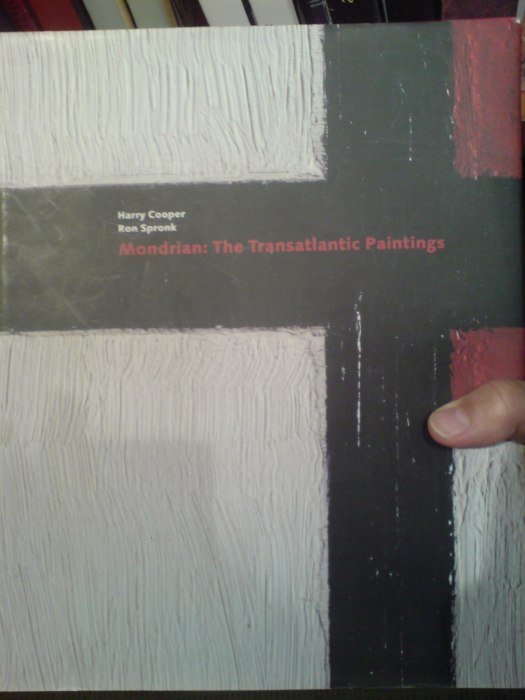

...his mentor remained Hans Hofmann, who helped him see how to construct a purely abstract picture, while his great inspiration was Mondrian, about whom Stout observed that "the tangible and sensational world was still the raw material for the universality which he would create for himself." In other words, Mondrian, like Stout, remained firmly connected to nature and the real world.Things that happened in 2007 can seem so long ago and far away. I need to hustle up some Stouts to look at, pronto.

January 4, 2011

I'm still trying to figure out quite what he said, but whatever it is, Doug Ashford said the hell out of it. Forget speaking or writing like this, I wish I could even think like this. Brains back on, people! Vacation's over!

Over all, our efforts in the Democracy project were to try to see how democracy happens at the site of representation itself, not just where information is transferred or built, but rather at the very place we recognize ourselves in performing images, where we have the sense we that we are ourselves, feel a stability that is hailed and recognized by others. A radical representational moment, whether collective or not, is one that suggests we can give ourselves over to a new vision through feeling, an experience linked to contemplation and epiphany. In this way no public description of another, in frame or in detail, can be presented as politically neutral. So when Group Material asked, "How is culture made and who is it for?", we were asking for something greater than simply a larger piece of the art world's real estate. We were asking for the relationships to change between those who depict the world and those who consume it, and demonstrating that the context for this change would question more than just the museum: a contestation of all contexts for public life. In making exhibitions and public projects that sought to transform the instrumentality of representational politics, invoking questions about democracy itself, Group Material presented a belief that art directly builds who we are - it engenders us.From Doug Ashford's "Group Material: Abstraction as the Onset of the Real," an adapted paper presented in 2009 at the "New Productivisms" conference at Museu d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona, as published online by the european institute for progressive cultural policies [eipcp.net via @mattermorph via @joygarnett]

January 4, 2011

Maybe it was the news, or those long family car rides over Christmas with his cousin's evangelical radio station going the whole way. But Frank Wick has of late been considering The Big Questions of Life, questions such as, "When The Rapture comes, will On Kawara have enough time that day to finish his painting?"

I guess the answer has been there all along in Kawara's audio piece, Kawara's Four Thousand and Four Years, B.C. and Two Thousand and Eleven Years, A.D.. He that hath ears, let him hear.

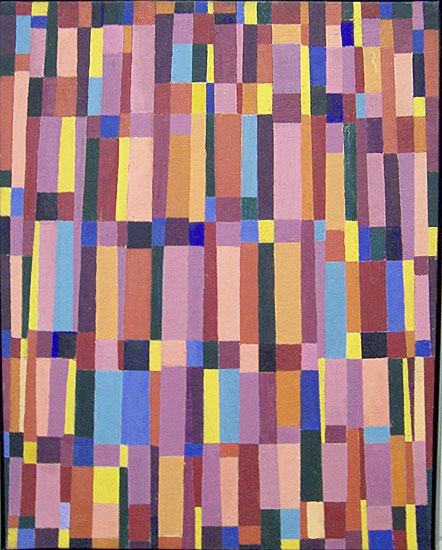

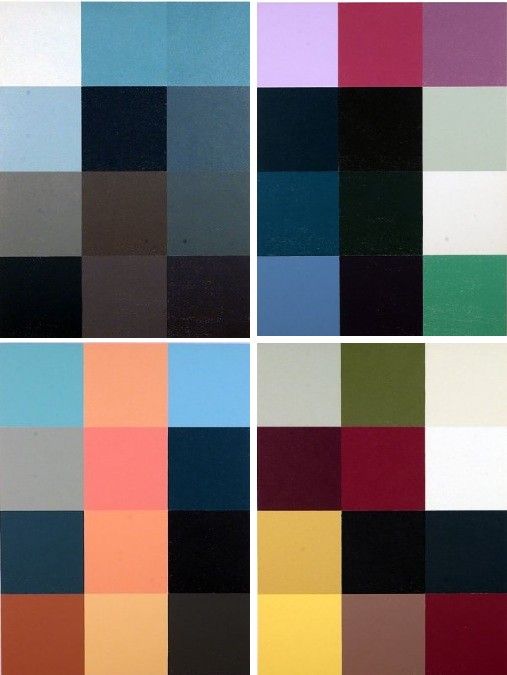

Holy smokes, it's been 15 months since I found the Dutch Camo Landscapes on Google Maps; just over a year since I started systematically screengrabbing them; a little less than a year since Google's particularly beautiful Delaunay triangulation distortion was replaced by a more typical pixelation algorithm; and about the same time since I last posted one of the "What I Looked At" installments, where I tried to figure out how to approach painting these things by studying the techniques of other hybrid, found, hard-edge, geometric digital, photographic, reductivist, surveillant, abstract, or Dutch Landscapes. Folks from Albert Cuyp and Picabia to Arthur Dove and Sheeler to Mondrian to Sherrie Levine [below].

The longer I take to think about how to paint without actually trying to paint, the more I keep accumulating and questioning potentially resonant work. And I wonder: what would it mean to consciously appropriate someone else's technique? if I taped my edges, would there be more of a connection to Odili Donald Odita? If I made little polygonal stencils and squeegeed, would it be too Brillo? Is there an implication in the kind of precise painterly edges of Mondrian as opposed to the surprisingly tentative edges of Sheeler, or the just-fill-it-in forms of Dove? Should I skip the paint, and just blow those bad boys up and print the hell out of'em on the biggest canvas/paper I can find?

It [basically, obviously] boils down to some ongoing uncertainty or doubt or skepticism or insecurity or whatever over whether these things should exist. Emphasis on things and should. Does everyone who makes stuff feel that? It's like Baldessari's classic fortune cookie of a painting, "I will not make any more boring art," but with the make in flux as much as the boring. I just remained unconvinced about the justification for these images as objects. [On the "bright" side, like the unshot film in the director's mind, the unmade artwork does remain perfect--for me, anyway.]

Anyway, all this comes to the fore because last summer, I saw images of some polygonal abstracted landscape paintings by Douglas Coupland, which were part of, or inspiration for, or somehow connected to, the Fall/Winter clothing and home furnishings colabo he designed for the Canadian retailer Roots. They were exhibited and for sale in Coupland X Roots pop-up stores in Vancouver and Toronto.

There was zero info online, so last summer and fall, but I deduced that they were digital reductions of iconic paintings by the Group of Seven, the early 20th century landscape painters who rather self-consciously set out to create a national cultural and visual identity for Canada via its landscape. Coupland's Roots collection was an extension of that national branding project, only he referenced the unifying forces of electrification, television, and moose logos.

At least that's what I gleaned from the web and press releases. I tried in vain to get any information on the paintings from Roots, Coupland, or his galleries, but it was total radio silence. So I ignored them back. Only now, as I check back, do I find that "culture guru" Coupland has a show up of the paintings, through this week, at Monte Clark Gallery in Vancouver. Faux-encrypically titled G72K10, the paintings turn out to be exactly what I thought they were.

"Thomson (Sunset), 2010, Oil on canvas, 58 x 72 inches" image: monteclarkgallery.com

To a point. Because though the captions say things like "oil on canvas" and "acrylic and latex" and "unique pigment print" it is completely unclear whether the images on the dealer's website are of the objects themselves or of their digital sources. Maybe it doesn't matter to Coupland. Here's how the gallery describes them:

By digitizing the likeness of specific works, Coupland has produced large-scale hard-edged paintings on canvas, presenting his own vision of the Group of Seven in 2010.Doesn't sound like he'd use something as retardataire as a paintbrush for a forward-looking project like that. Though it's hard to tell from the jpg, the date on this unidentified type of limited edition print being auctioned next month by the Writers' Trust looks earlier than 2010. Or not.

So while I still can't decide if my painterly obsession is a vice, Coupland's project is at least makes clear that materialist indifference in the pursuit of digitized aestheticism and conceptual slickness is no virtue.

January 2, 2011

A dismal, depressing subject can be made enjoyable by great writing. And the spirits can be lifted by an awesome photo at the end. These are my takeaways from Richard Hendy's travel/history/economics/politics/apocalyptic decline essay on Amakusa, a hardscrabble group of islands near Kyushu, Japan.

Hendy's blog Spike Japan documents the underside and overlooked, and Amakusa certainly sounds like it's had the short end of the stick since forever, basically, and all they have to show for it is a 15-year-old, $120 million Bridge To Nowhere--designed by Renzo Piano.

But this incredible photo gives me hope. I'm transfixed by this pachinko sign. I mean, just look at those lines. The neonya-san who made that is literally drawing with light in space here. Is there a kanji-based, gestural tradition within the Japanese neon signmaking industry? Have Zen brushstrokes been translated or reperformed and fixed in 3D glass tubing? Or maybe it's Action Painting, frozen in time and space instead of dropped onto the canvas in the barn in Springs?

Perhaps Peter Coffin's 2004 sculpture, Untitled (Line after B. Nauman's The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths) 1, isn't abstract at all, but documentary. Perhaps the topic could be addressed by a panel discussion at a future symposium, after Amakusa's calligraphic lighting sector has been revitalized, and the island has claimed its rightful place as the Japanese Marfa for the neon arts.

1 which, hello, is now in MoMA's collection.

January 1, 2011

Tom Scocca posted about the story just before Christmas, but apparently, Mao Zedong was a Bruce Lee fan.

That's how the Chinese press is reporting the story of Liu Qingtang, [刘庆棠], a ballet dancer and close ally of Mao's wife Jiang Qing, who, as the deputy minister, was put in charge of films at the Ministry of Culture.

Mao was encouraged because of cataracts to cut down on his reading, and to switch to film. Liu was charged with programming and procuring prints for Mao's private screenings.

Scocca picked the story up from Raymond Zhou in China Daily, but Liu's account was first published in November in the Yangcheng Evening News, a major daily out of Guangzhou. It was posted online a few weeks later. Here's the Chinese, "毛泽东有多迷李小龙?", and a choppy Google translation, "Mao Was a Bruce Lee Fan?" [It's remarkable how far Chinese-English autotranslation still has to go. We're barely at Babelfish levels here.]

Liu says his story is from 1974:

Mao Zedong's like to watch movies there are several categories: first, the international award-winning film; second film biography, "Abraham Lincoln", "Napoleon," he loves; third is like watching garden scenery film, like most British films. Often, Mao heard good movie, the file will be down to watch, watch movies right away, very happy.. At some point, then, Liu traveled to Guangzhou, and on to Hong Kong, where he had not a little bit of trouble getting prints of Lee's films, The Big Boss, Fist of Fury and The Way of the Dragon, from the wary movie mogul Sir Run Run Shaw.

Where Mao would watch only a few minutes at a time, taking up to ten days to finish another film, he apparently sat straight through Lee's movies, and even demanded repeat viewings. Liu was afraid to send the prints back to HK, in case Mao asked to see them again.

The incorporation of Mao into the Bruce Lee fan club, the American-born, Hong Kong-raised, one-quarter German Lee [who is known by his given Cantonese name, Li Jun-fan (李振藩)] was timed with the premiere on CCTV6 of a documentary, "Legend of Bruce Lee," which debuted at Beijing University. It all serves to retroactively position Lee as an inspiring, nationalistic hero of all Chinese, including the Mainland, where he was unknown during his lifetime.

And it all makes me wonder what was actually going on film-wise in the PRC during the tumultuous waning days of Mao's rule. Because there are some contradictions and gaps in Liu's story as it's reported:

Wikipedia, which has the only actual date I can find so far, says Liu was installed as Deputy Culture Minister in February 1976.

Jonathan Clements' 2006 biography of Mao dates the cataracts to 1974, but also says that Mao was nearly blind, and his slurred speech could only be decoded by his nurse.

As Reeve Wong pointed out to China Daily, Bruce Lee's films were actually produced by Shaw's rival studio, Golden Harvest. It's not clear how or where, but Liu still insists that he got the prints from Shaw.

Given the difficulty in tracking down prints of Hong Kong's most popular films, I have to wonder what "international award-winning films" and biopics Liu was able to get his hands on. I mean, was there a copy of John Ford's 1939 film Young Mister Lincoln laying around a cinema after the Revolution?

And the big question, did he watch Michelangelo Antonioni's epic 1972 documentary Chung Kuo? Antonioni originally shot Chung Kuo/ Cina as a left-to-left cultural gift, with Communist Party participation and supervision. After it came out, though, Madame Mao & her cinematic comrades denounced spectacularly as a capitalist reactionary insult to the Motherland.

A lengthy bio of Liu Qingtang at hudong.com says that in 1976 as the Gang of Four maneuvered for post-Mao power, Minister Liu personally oversaw the production of three "hit films," Back [反击]、Grand Festival, [盛大的节日], and Fight [搏斗] which attacked Deng Xiaopeng.

After Deng regained and consolidated power and began undoing the effects of the Cultural Revolution, Liu followed the Gang of Four into public disgrace, trial and jail. But he's apparently out now, and doing fine, if not quite keeping his dates and titles straight.