Like everyone else reading it on OSCAR NIGHT®, Andrew Hultkrans’ 1995 Artforum interview with Kathryn Bigelow gave me hope for the films-by-artists genre, if not quite from the direction people might expect. To hear a double OSCAR® winner say of film noir, “That’s how I moved from art to film, so to speak: I went through Fassbinder on my way to noir.”

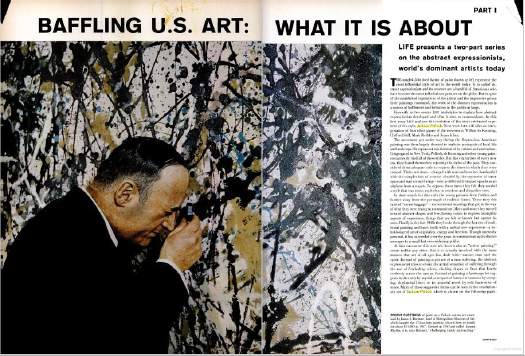

ANDREW HULTKRANS: It’s quite a leap from Conceptual art to the culture industry. KATHRYN BIGELOW: It does seem like a departure. I was studying painting at the San Francisco Art Institute and one of my teachers put me up for the Whitney Program, so I went. This was ’73 or ’74, when Conceptual art really came to the fore. I did a couple of videos with Lawrence Weiner, and I worked with Art & Language, an artists, group who were critiquing the commodification of culture. So I was very influenced by them, and my concerns moved from the plastic arts to Conceptual art and a more politicized framework. And I became dissatisfied with the art world – the fact that it requires a certain amount of knowledge to appreciate abstract material.

Film, of course, does not demand this kind of knowledge. Film was this incredible social tool that required nothing of you besides twenty minutes to two hours of your time.

Wait, Lawrence Weiner videos? No, not that one.

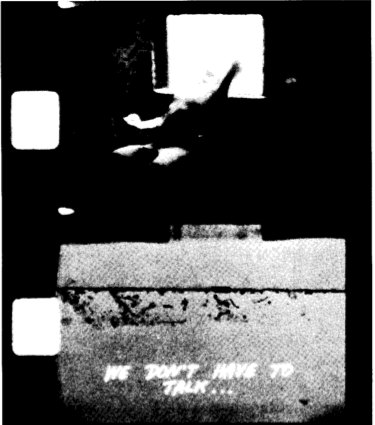

Bigelow appeared with Sharon Haskell in Weiner’s Done To, 1974, which Alice Weiner describes as:

…simple camera frames which are silent and/or unconnected to a complex soundtrack running parellel [sic] to the images. There are brief instances where image and sound meet; however, the majority of the images are overtaken by at times symphonic, at times cacophonous soundtracks which displace the normal filmic viewing experience. The standard film format for going from frame to frame — and then and then and then — is what the film is concerned with.

E.A.I. has a fuller synopsis, and VDB has a tiny clip viewable online.

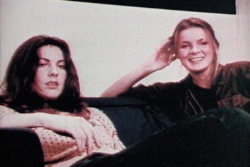

She also appeared briefly in Green as Well as Blue as Well as Red, 1976, [above, vdb clip here] where her off-camera conversation with Weiner is mixed over the shot of two women reading from a red book at a rainbow-painted table.

Bigelow is credited as an editor and production/script consultant on Weiner’s first narrative-based work,Altered To Suit, 1979 [vdb clip]. From Alice Weiner’s synopsis at EAI:

“The mise-en-scene, the whole story, takes place in one location, the artist’s studio. A delicate psychological allegory on ‘a day in the life of’ anchors the displacement of (filmic) reality and the alienation of the (players) self. Devices such as incongruity between the image and the soundtrack, odd camera angles, and plays on objective focus are integral and explicit components of the narrative.

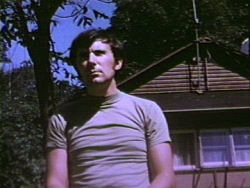

Altered To Suit overlaps with the beginning of Bigelow’s own film work; she made her first short, The Set-Up, which she completed in 1978 while at Columbia.

Bigelow mentioned two other very early, art film-related gigs in an interview with Gavin Smith published in Jessmyn & Redmond’s 2003 anthology, The Cinema of Kathryn Bigelow: Hollywood Transgressor [seriously]: She appeared “for about five seconds” in a Richard Serra video, and she shot some B-roll for a Vito Acconci installation.

[He] needed these slogans and phrases on film loops that would play on the wall behind him during a performance piece he did at Sonnabend in a rubber bondage room he created. The job was to film these slogans. I’d never worked with a camera. I was starving to death. If I hadn’t been at the brink of economic disaster, I think I never would have had all these detours.

I haven’t been able to figure out which Acconci performance/installation Bigelow’s referring to. Acconci showed at Sonnabend in 1972, ’73, and ’75. But 1972 was Seedbed, where the artist hid under a ramp masturbating for several weeks. The 1973 performance, Recording Studio From Air Time consisted of a video feed of Acconci in an isolation chamber/ confessional for two weeks, analyzing a romantic relationship in a mirror. I haven’t found a description of the 1975 show, but MoCA curator Anne Rorimer has written that after 1974, Acconci “dismissed himself as a live presence” and began using video and audio of himself in his performances. If her description and timeline is accurate, I’m guessing this is what Bigelow filmed, and what Acconci showed in 1975.

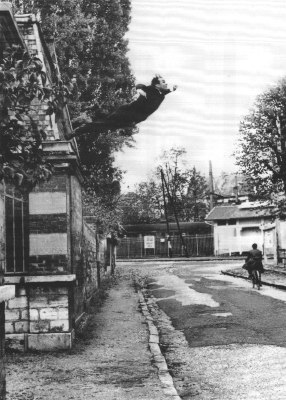

While Googling around to identify the Richard Serra video with Bigelow’s cameo, I found Bettina Korek’s fresh post at Huffington, about Bigelow’s art career. She links to “Breaking Point: Kathryn Bigelow’s Life In Art,” an exhibition at castillo/corrales in Paris which has been on since mid-January and continues through next weekend.

The most likely possibility for the Serra video is his 1974 game show/game theory critique of TV, Prisoner’s Dilemma, in which Spaulding Gray and Leo Castelli are supposedly at risk of getting stuffed in a SoHo basement for 50 years [The video was shot at 112 Greene Street, the first home of White Columns. 16miles.com has an installation shot from White Columns’ 40th anniversary show of stills from Prisoner’s Dilemma.]

Sure enough, sometimes it still makes sense to get up and walk across the room, because Serra discusses it two interviews, with Liza Bear and Annette Michelson, in Richard Serra: Writings/Interviews.

With Michelson, he explains how the angry art world-y studio audience tore down the screen to save Castelli. And in the notes for Bear’s earlier interview, the video’s credits include: “D.A.’s Secretary: Kathy Bigelow.” So there you go.

UPDATE: BUT WAIT, THERE’S MORE! Francois from castillo/coralles emailed with some more information: “Vito Acconci, when visiting the show, mentioned [Bigelow] had collaborated on his installation ‘Pornography in the classroom’, originally conceived in 1975.”

Which should put the issue to rest, except that “PITC” doesn’t seem to fit with Bigelow’s account, either of the work she did [filming slogans and phrases], the installation/performance [bondage equipment, with video projected behind Acconci], or the venue [Sonnabend]:

“Pornography in the classroom” as it’s known today is a slideshow of images from 1970s porn magazines, projected over a single channel video monitor [originally Super8mm film] of an ascending and descending penis, which is accompanied by the artist’s voiceover [“Thar she blows!”] It was shown at Gladstone in 1998, and the Kramlichs [of the San Francisco video art-collecting Kramlichs] bought it. It’s an edition of one, though Acconci apparently retains the master slides and film. The Kramlichs donated “PITC,” along with many other of their video works, to the New Art Trust, a consortium of museums and archives.

In a fascinating-to-video-collectors article in the 2001 Journal of the American Institute of Conservation, Timothy Vitale all but says flatout that the current incarnation of “PITC” is not just artist-remastered, it is completely new media. Neither the slides nor the video show any traces of aging or reformatting. If Bigelow did, in fact, shoot footage for “PITC,” her camerawork has almost certainly been replaced.

Of course, I’d think that, given her lucid discussions of her and others’ conceptual and performance work, I don’t think Bigelow would confuse “phrases and slogans” with “bobbing penises.” My guess is she didn’t work on “PITC”. And if she did, she may not want to talk about it.