In 1961, Hazleton Laboratories, a pioneering biological sciences testing company based in Falls Church, Virginia, was growing rapidly. For one of their expansions, executives and scientists were given allocations to buy cutting edge abstract art for their offices.

Which was fortuitous because, as a group of forward-thinking Hazleton wives in McLean told their husbands, their bridge club was actually sponsoring a very promising young abstract painter named Bidwell. Perhaps after a bit of vetting by some galleries in the District who know this kind of art, the company might consider collecting Bidwell’s work?

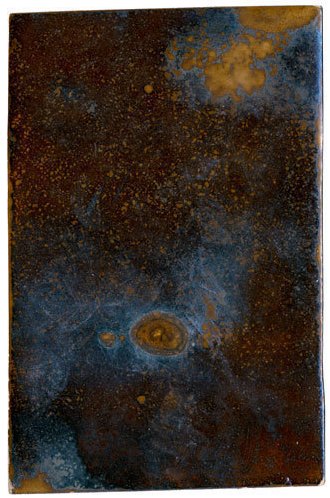

So the wives took Bidwell’s paintings to three galleries in DC for evaluation. One canvas, “Snow in July,” which was executed with housepaint and a stick in an action painting style reminiscent of Pollock, was said to exhibit a “tremendous sense of design and color,” and might sell, the dealer said, for as much as $150. I believe that is “Snow In July” on the left in the photo above, being held by Mrs. Jiro Kodama. The painting Mrs. Lewis Van Hoose is holding is unidentified.

The bridge club arranged a private showing of Bidwell’s work–and then revealed to their husbands that the whole thing was a scam. For six months, the women had taken turns painting the works themselves during their bridge games. Their original plan was not just to sell the work to Hazleton, though; according to the front page story in the Washington Evening Star, it was really to “show how modern art can be phony.”

I first learned of the McLean bridge club’s “artistic slam” from Nina Burleigh’s 1998 book, A Very Private Woman: The Life and Unsolved Murder of Presidential Mistress Mary Meyer. She cited the Star article as an example of postwar Washington culture’s derisive, even philistine view of modern art. The suburban wives’ parodic production is almost a perfect mirror of the amateur-yet-serious pursuit of abstract painting by the Georgetown wives Burleigh cast as Meyer’s peers.

Of course, there are many problems with this story, at least as it comes down. Conflating McLean and Georgetown makes as much sense as Greenwich and Greenwich Village. And the Bidwell exercise only came to light after the fact, and was only ever depicted as a generalized condemnation of modern art’s scammy bankruptcy: the wives declined to name the actual galleries they claimed to have visited, and the reporter, Gilbert Gimble, didn’t bother to check, or to question the wives’ misrepresentations of the work. And no actual art experts were asked about the project; it was all just a sensible, amusing, suburban pin in the “high-brow” art world’s balloon.

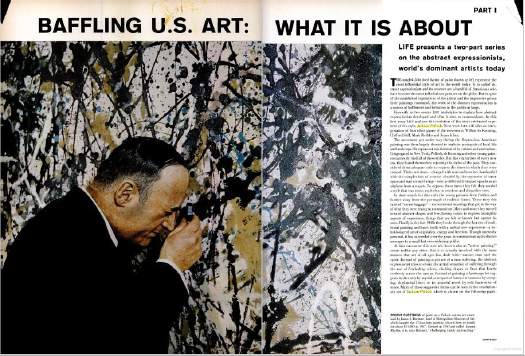

But as contemporary critique, the Bidwell incident was hardly novel, or even up to date. By 1961, Abstract Expressionism had been presented as America’s official Dominant Art Form–or at least LIFE Magazine’s–for over a decade. LIFE kicked off the “debate” over whether Pollock was “America’s greatest living artist,” way back in 1949. But even in 1959, they were still publishing multipart, pseudo-analytical service pieces for understanding “Baffling U.S. Art”.

What if, instead, Bidwell were taken at face value–or at least at the face value afforded by decades of art critical hindsight? Are there feminist implications to the reality that parody was apparently the only means available for these women to engage the prevailing cultural discourse? [Their next collaboration, they said, would be “to write a sexy novel.”] Or that the only way for women’s art to make the front page of the paper is as farce?

Reading about the bridge club’s actual process and project, I’m struck by how it resonates with the works of later artists and collectives, from Paul McCarthy to Matthew Barney to Karen Finley to Gelitin and Reena Spaulings and Bruce High Quality Foundation.

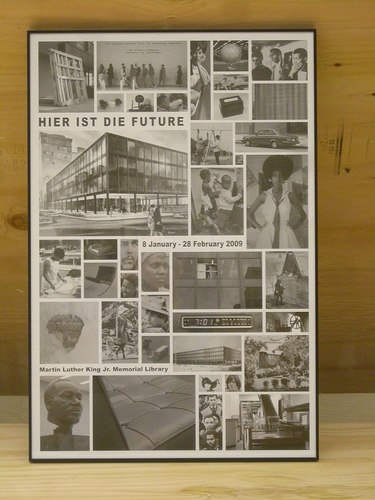

I’ve included the entire text from Gimble’s article after the jump. It ran on page A1 of the March 14, 1961 edition of the now-defunct Washington Evening Star, and is available via microfilm at the DC Public Library. Make of it what you will.

Continue reading “Bidwell And The Lost Virginia Abstract Expressionists”