So “Untitled” (Go-Go Dancing Platform), 1991, is unique, but it is not the only one. Now that it has sold “a serious hold” and a $US16m asking price, let’s take a look at the six [!] related works Felix Gonzalez-Torres made. And then decided were not works after all. What are they, where are they, and what is to be done with them?

Author: greg

Beuys Collector Collection Shelf

After working with Joseph Beuys on his multiples for many years, Jörg Schellmann made small editions of four pieces of Beuys-designed furniture in 2008, 22 years after the artist’s death.

Schellmann Art’s description says all these pieces—three tables and a bookshelf, no vitrines, no felt—were originally made in 1953 for an unidentified collector in Dusseldorf. I’m not sure why they’re being so cagey. In 1953 Beuys’s two major collectors were brothers: Hans and Franz Josef van der Grinten. Besides collecting his work, the van der Grintens gave Beuys his first show, in their house, let him move in with them, and represented him in their gallery. Was it somehow not them?

The original table Beuys made was later incorporated into an artwork, and then into Block Beuys, the seven-room gesamtkunstinstallationwerk at the Hessisches Landesmuseum in Darmstadt. A controversial renovation and conservation project, including a March 2008 symposium on what to do with the original jute wallcoverings and carpets, was the immediate context, if not the specific impetus, for the collection. [spoiler alert: they’re still gone.]

Anyhow, I like this shelf more than I expected. And I like how the lighting in this example, which sold for much less than retail at Phillips in April 2020, right in the mouth of the pandemic, shows the ladder-like structure.

If you can’t wait for another to turn up, the form could be replicated in Ikea IVAR components, but not its details. Though the shelves look to be straight up lumber. And built up? The verticals are pinned to the wall, and are rounded, but and the shelves are neither. The desks all have extensive joinery, so though the carpentry details that will keep the whole thing from wobbling itself to death in actual use are not apparent, there must be something. Right?

Joseph Beuys, Royal Pitch Pine, 1953/2008 [schellmannart]

All In A Day’s Work

Hauser & Wirth showing Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ “Untitled” (Go-Go Dancing Platform) at Art Basel Unlimited this week. Seeing a video on H&W’s insta of the dancer hopping off the platform and heading out of the halle, accompanied, like a Disneyland character, by a handler, reminds me of artist Pierre Bal-Blanc’s 1992 video work, Employment Contract.

Bal-Blanc was a go-go dancer for the 1992 installation of Felix’s work at the Kunstverein Hamburg, for a show called “Ethics and Aesthetics in times of AIDS.” Employment Contract is a wordless slice of Bal-Blanc’s life that happens to have a brief go-go dancing stint in the middle of it.

One of the tenets of “Untitled” (Go-Go Dancing Platform), reaffirmed just a couple of weeks ago when the Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation published an in-process version of core tenets for the work, is that the dancer’s schedule is their own, and it is undisclosed. The dancer chooses whether to share their schedule with the exhibitor, and the exhibitor is to take care not to disclose it, and to provide adequate accomodations for the dancer to go about their business. From the viewing, and even the exhibiting standpoint, this work of Felix’s entails a high degree of uncertainty, and a very low probability at any one moment of there being a dancer dancing.

Bal-Blanc turns this sense of expectation entirely inside out. The video camera tracking him as he jogs through the streets of Hamburg gives no hint at all of what is to come; he’s just a guy, jogging, in jorts. The surreal absurdity of him walking into a museum, unlocking a supply closet, stripping down [to silver and black briefs, a kludgey two-tone outfit that would not pass muster with the Core Tenets crowd], and grooving in an empty gallery for several minutes, defies narrative logic. And yet he goes right on with it, and back out of the museum. All in a day’s work.

This question of context and expectation is one of the perennial sources of power for Felix’s work, especially this one. Encountering a go-go dancer in a museum might feel as disorienting as a pile of candy you can eat from. More than 30 years on, Hauser & Wirth’s instagram comments are somehow still full of people still confused or contemptuous of this work as art. And while art world folks have certainly consumed and processed Felix’s work fully, seeing this piece, from this gallery, at an art fair, the least wild thing about it is the dancer.

[next day update]: indeed, it looks like the Core Tenets got updated just in time, because the work that had been on “permanent loan” to the Museum St. Gallen is for sale by the Swiss collectors who’ve owned it all along. Donald Judd would not be surprised. It does make me want to take a new look at the five go-dancing platforms and lighted pedestals listed in the “non-works” section of the CR.

Maurice Darantiere, Ulysses Cover Proof

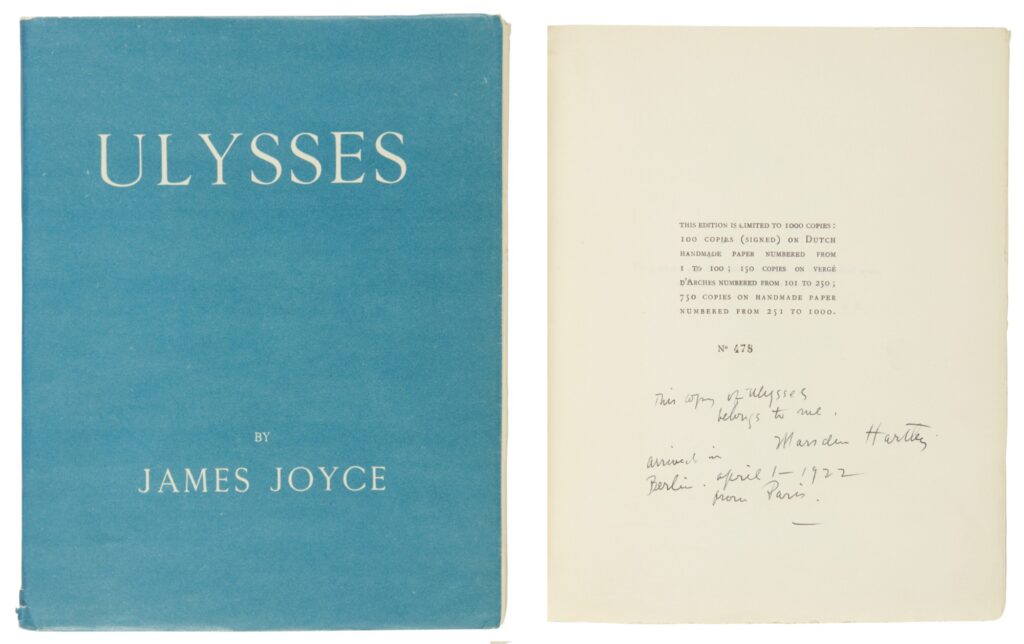

I knew the story about Joyce wanting the cover for Ulysses to be the blue of the Greek flag. But I did not know that he ended up giving the little Greek flag hanging in Shakespeare & Co. to his artist friend, Myron Chester Nutting, to match the color.

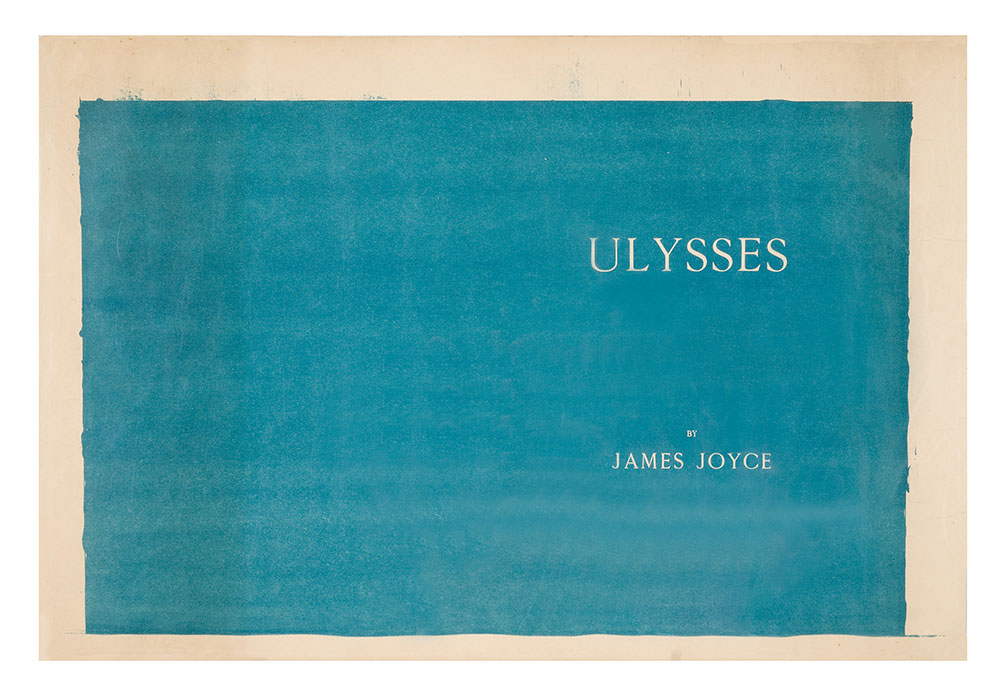

I learned this from The Morgan Library’s online exhibition celebrating Ulysses‘ centenary, which includes the extraordinary lithograph above, the final proof for Joyce’s Ulysses cover, prepared by the Dijon printer Maurice Darantiere.

At first the bleed around the edge and the brushmarks made me wonder if there was an ur-monochrome painting, a Nutting original, but I think not. The stone or the plate was painted with a solid field, which Darantiere printed using ink prepared to Nutting’s specification. The title seems to be set in negative, masked so the unprinted paper shows through.

Maybe I must now make the entire cover, as printed, not just the front. I feel like it should match the dimensions of the book, and the page inside, but those bleeding edges do call to me. Either way, I obviously must make it like this now.

And I have to get the color right. Is it best to match the modern color of Marsden Hartley’s copy? Is it even possible to match the original, given that they’re all 100 years old, too? Do I try to match the proof? Is it a Ulysses conservation standardbearer? Nutting apparently warned Joyce that the blue would fade, and it did?

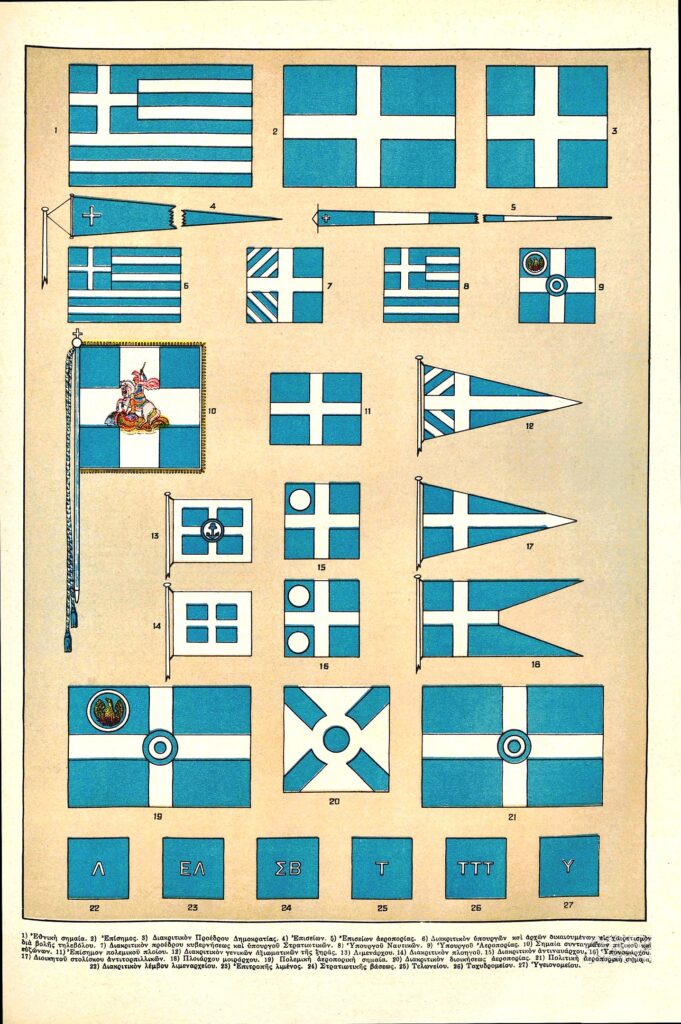

I’ve seen discussion of Joyce’s Greek flag blue not actually matching the Greek flag’s blue, that perhaps the Shakespeare & Co. flag had faded, as well as the books. But Ulysses matches the color of the Greek flags reproduced in this 1934 encyclopedia plate. Honestly, I can see the appeal.

Getting the Right Blue on the Cover [themorgan.org via @mclees-fiona via @joshuajfriedman]

Previously, related: Untitled (Joyce Hartley), 2025

At least Luigi Lucioni got his copy of Ulysses back

Tania Bruguera Terror Chic

Coming in 2005, smack in the middle of the Global War On Terror™, the 51st Venice Biennale may have been #toosoon for Tania Bruguera to drop two editions named Terror Chic. Twenty years and a few revolutions in, let’s see how it’s going.

One edition is what we might now call the Terror Chic Capsule Collection: a group of fifty objects—mirrors, messenger bags, t-shirts, stretched canvases—each printed with what Edition Schellmann calls Bruguera’s “thought-provoking slogan, ‘NEVER FORGET YOUR FIRST REVOLUTION.'”

The other is more interesting: a Terror Chic metal stencil in an edition of 200, “to be used to print slogan on T-shirt, bag, wall, car, or any other object.” Now we’re talking. Bruguera’s stencil hasn’t even sold out yet, but it’s efficiency and durability have surely already spawned several revolutions, as well as a whole trend of fundraising edition stencils.

Meanwhile, if you’re in the market, never forget to shop around. The revolution can be had with a vip discount.

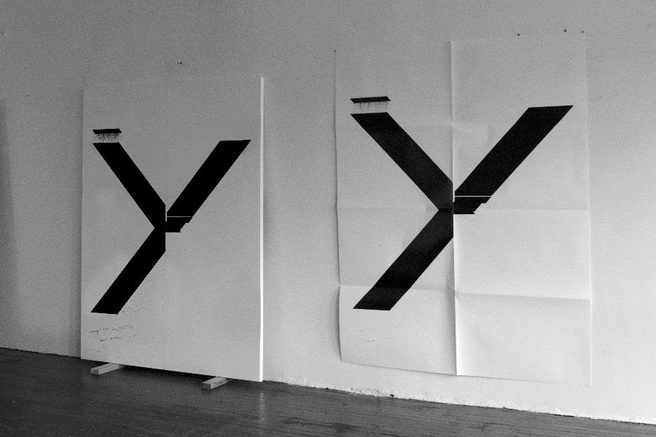

Wade Guyton Beyeler Facsimile Objects

The Fondation Beyeler has just come out with your first Art Basel impulse purchase: two full-scale Wade Guyton prints of paintings showing at the Beyeler right now. Around here we’d call them facsimile objects, but they are very much what Wade does and how he does it.

For six years, from 2014-19, Guyton made full-scale print facsimiles of his paintings as fundraising editions for Printed Matter. They were all posters of earlier black X-on-white paintings, and folding them by hand felt like part of the concept. From the proofs installed at the Beyeler, that does not seem to be the case anymore. These look as flat as the day they rolled off the Epson.

TFW I thought I’d seen these before, not just at the Beyeler, and I was like, “Duh, that’s his MO.” But no, I don’t mean in the “all Guytons look alike” mode. I mean in the sense that I felt like I’d seen these paintings before, at Guyton’s 2023 show at Matthew Marks. The X painting, WG5707, depicts a different scan of a different, earlier X painting than the one at Marks. And in fact, the 2024 Beyeler painting in the 2025 Beyeler print has striations that look like a photo of a monitor of a scan of a transparency of a painting, rather than just a scan of a transparency of a painting.

But the other one, WG5703, the photo of Guyton’s studio floor, is, in fact, the same photo, though not the same painting.

Guyton likes to paint, photograph, and repaint the floor of his studio, and these Clyfford Still-like layered abstractions are the glorious result. But what these two paintings show is not found wear & tear. The tape, the shoe[?] in the lower left corner, the separations [not just layering, it turns out] of color. This is the same photo, in different states, printed on canvas, twice. Three times, actually; the Beyeler already has another variation from 2021.

For a long time, Guyton was known to use the same files [.doc, .tiff], and give attention to the accidents and variations of the printing process. He staged multiple shows with identical layouts of images made from the same monochrome image, bigblack.tiff, and even sent five nearly identical paintings to his five dealers spread out around the Messe at Basel.

But from observing these little differences in the same content, Guyton has expanded his source image folder to include screenshots of the Times, and photos of his studio, his work, and his life. His 2021 show at Marks in LA included images of Guyton recording his temperature. In 2023 there were paintings made of photos of protests, and a Manet ham.

As the vagaries of printing become absorbed into the language of his work, Guyton has expanded what he says by making work of what he sees. His work, his shows, images, and the world around him, have all become animating subjects of his mature process. Mature, but not static; processes are revealed in between the finding and the printing. As these two floor paintings show, the images flowing around him may also be manipulated, altered, and created.

At first I thought the recursiveness was new, too, but I think it was always there; the works, their shifting formats, their nested titles, their numbering system, all make us aware of the artist’s awareness. The beauty of that churn, that cycle, of making and showing and remaking, is a compelling subject for at least a hundred people going to Basel for the 20th or 30th time for buying and selling. One hundred plus ten artist proofs.

Previously, related:

Waderunner

Wade Guyton [Manet] Simulacrum Facsimile Object

It’s the little differences

A Pile of White House Bricks

What’s that, you say?

VERY RARE HISTORICALLY IMPORTANT COLLECTION OF WHITE HOUSE BRICKS?

I AM LISTENING.

Enslaved people made the bricks for the White House from clay on or near the White House grounds at least twice. After the White House was burned in 1812, most of the original 1792 bricks were too damaged to use in the 1814-17 reconstruction. The 1817 bricks were removed during the 1948-52 gut reconstruction of the White House by President Harry s. Truman. 95,000 went for projects at Mount Vernon. 10,000 went to a project at Fort Myer. A New York congressman bought White House bricks left over from the Fort Myer pile, along with 1600 lbs of White House stone, and stored it at some guy’s farm for a while. When came to pick up most of it, he left this lot of 166 bricks. “This may very well be one of the last large groups of White House bricks in public hands,” says the Shenandoah Valley auctioneer Jeffrey S. Evans.

I’m trying to imagine the excitement if these original White House bricks were returned to the White House, or if they were exhibited publicly near the White House today. Or tomorrow.

The bricks will be auctioned June 28, 2025.

Lot 2124 | VERY RARE HISTORICALLY IMPORTANT COLLECTION OF WHITE HOUSE BRICKS, est $10-20,000 [jeffreysevans]

Previously, related: Untitled (George Washington’s Coffin), 2016

[few minutes later update: It’s my brick in a box]

Two Metal Things At Christie’s

According to the Alexander Calder Foundation, there were 61 pieces of jewelry included in the artist’s first retrospective, Calder Mobiles, at the George Walter Vincent Smith Gallery in Springfield, Massachusetts, in November 1938. Was Encircled Star, 1938, among them? Christie’s doesn’t say. All they know is that Anne Bass bought it in 1972, when she was 31.

It is also not clear whether the similar necklace from 1937, in gold wire instead of steel, was not available, or if Bass figured steel was safer for wearing on the subway in the 70s.

And speaking of celebrated metalwork of the ruling class, this rocaille inkwell. Holy moley, how is this real? It has resulted in the following words, a kind of poetry, at once luxurious and terrible, which I reproduce here in French and translation:

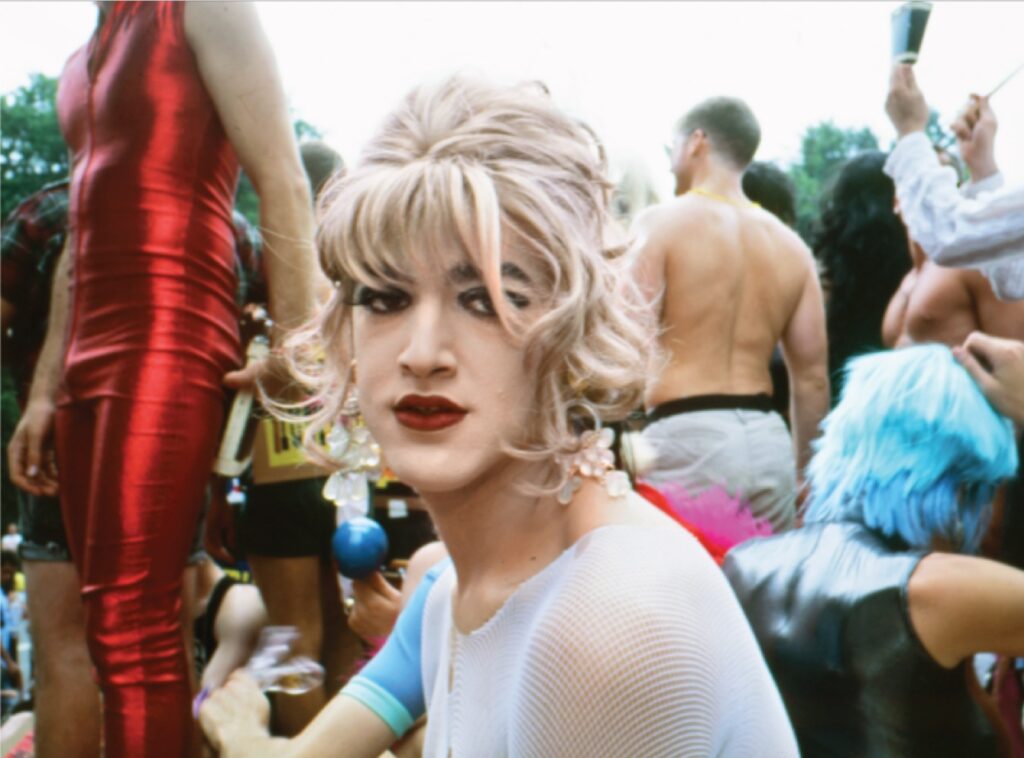

Continue reading “Two Metal Things At Christie’s”Nan Goldin Time-Limited Benefit Prints for Trans Justice

Nan Goldin has published two prints to raise money for trans justice-related organizations: the Leslie Lohman Museum, the Sylvia Rivera Law Project, and the Trans Income Project.

One’s Wigstock era iconic, the other pandemic freshness. They’re available through June 26, 2025. [leslielohman via hyperallergic]

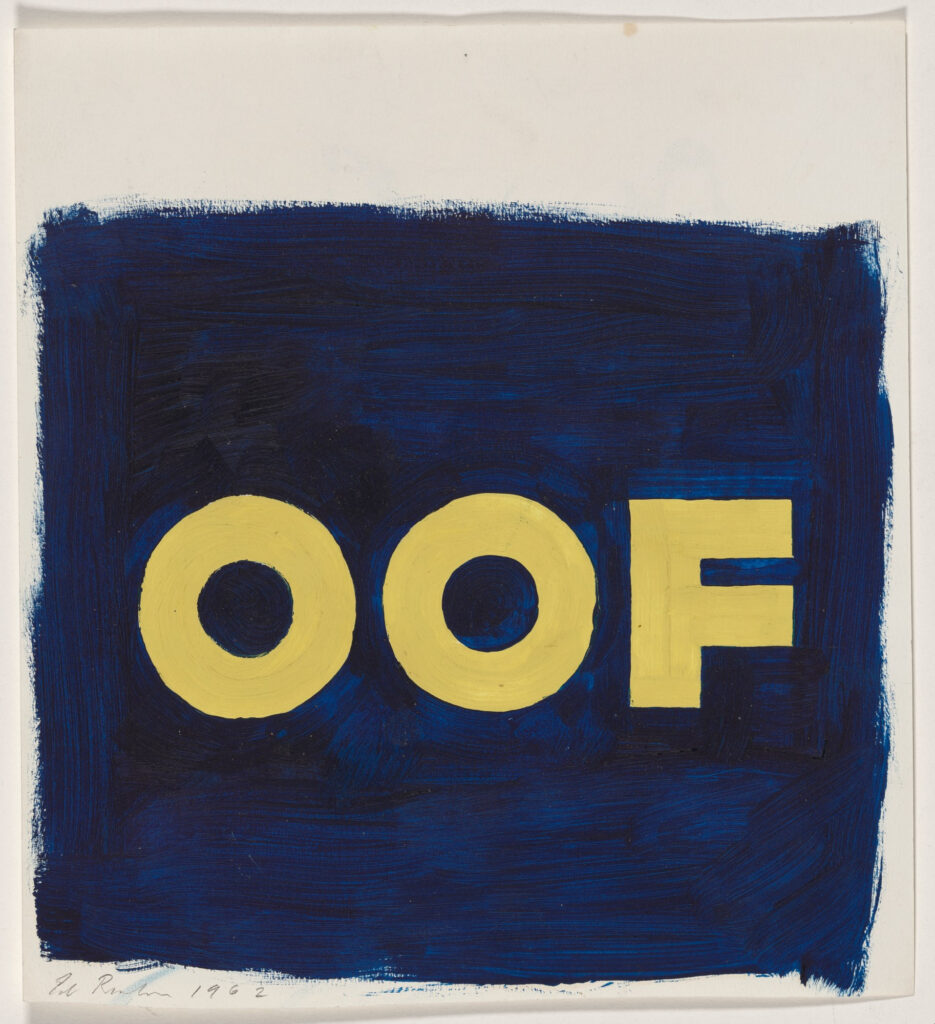

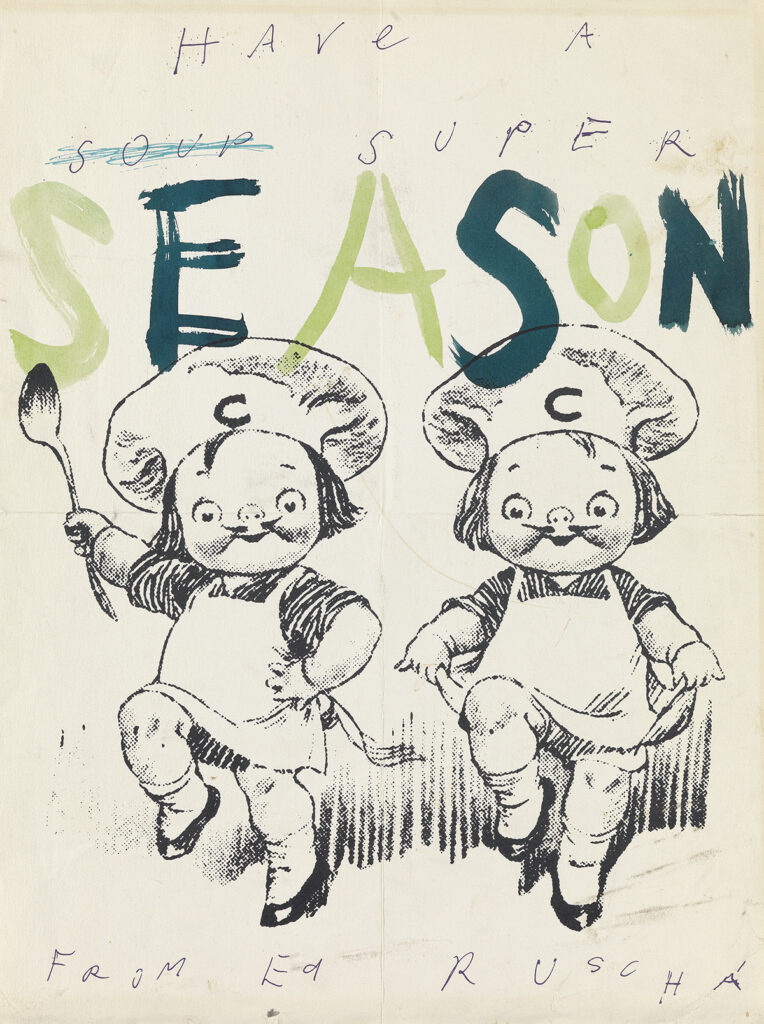

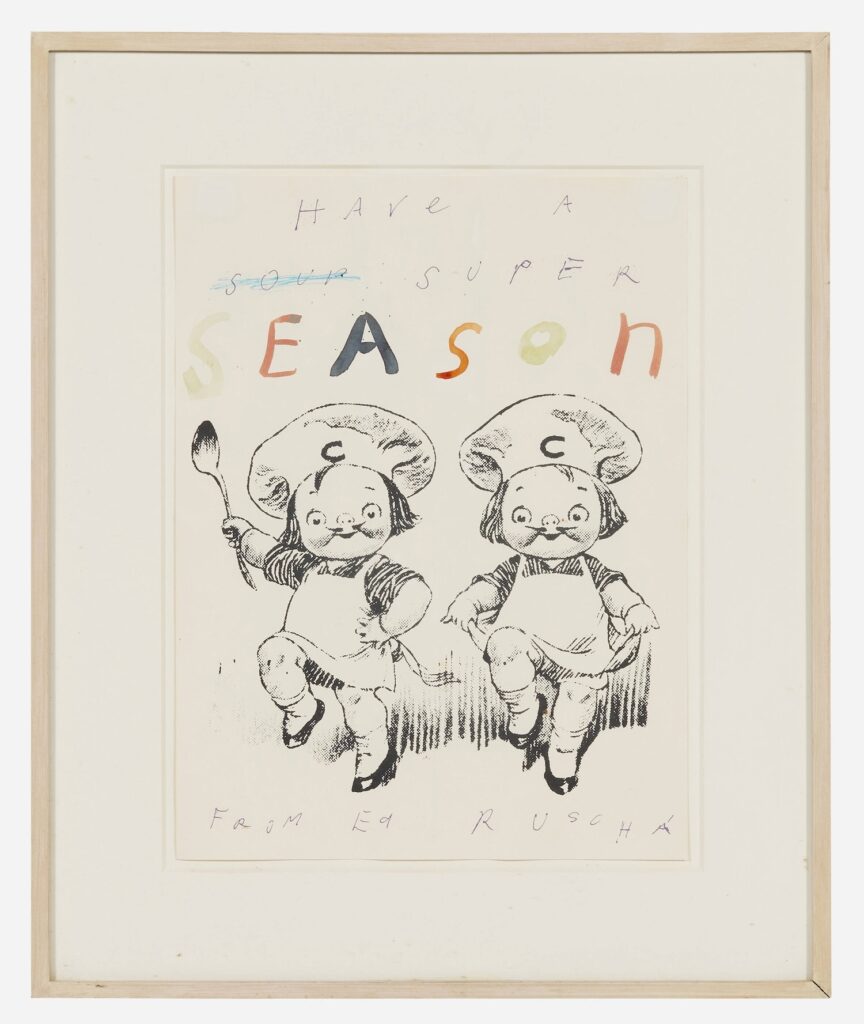

Campbell Kids From Ed Ruscha

The National Gallery has acquired an incredible study for Ed Ruscha’s OOF, but, amazingly, that is not important now. Because on the back is this:

These are the Campbell Kids, used to sell soup. What are they doing on the back of Ed Ruscha’s study? I think they were left over from his 1960 Christmas card.

This one sold at Swann along with a whole stack of Ruscha deepcuts. The Campbell Kids have been lifted from a print illustration, obviously, but seeing them both, it turns out the “From Ed Ruscha” handwriting is printed, too.

Amazingly, there is another one coming up for sale, if the emperor allows it, in Los Angeles in two weeks. So the OOF sheet had the “Have a soup super” trimmed off. How long did Ruscha use his leftovers as scratch paper? Are there Campbell Kids on the verso of any other drawings? So many questions!

What I do know is that this LA Modern image, without the OOF oil soaking through, will be easier to make a t-shirt from. Stay tuned.

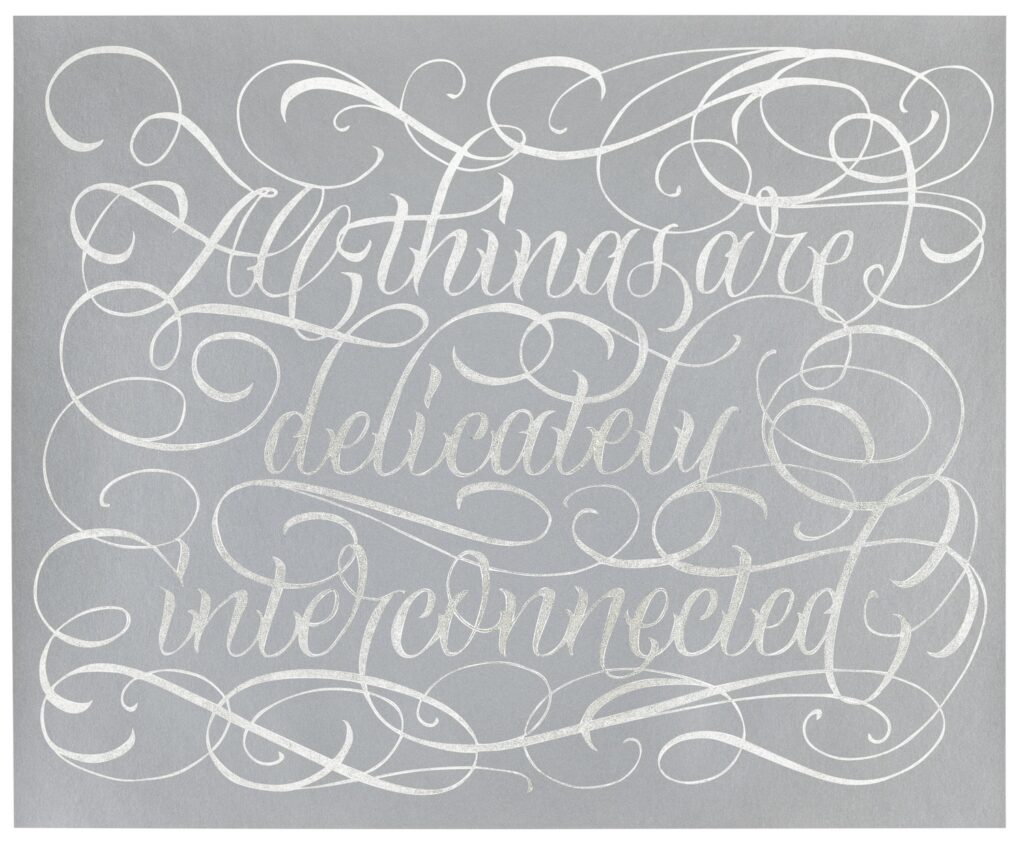

Jenny Holzer Calligraphy

In April 2020 I was not quick enough—nor, tbqh motivated enough—to run down one of the prints Jenny Holzer created for Hauser & Wirth as a fundraiser for Earth Day, which then also became a fundraiser for the WHO’s emergency COVID response. But since then, their unabashed etsy calligraphy has really grown on me, and makes me want to see “Live Love Laugh” carved into an exotic granite bench.

Fortunately, all 100 original buyers were flippers, because they come up for sale pretty regularly, unframed. And, after donating portion of the proceeds to support auction houses in need, they usually get most of their original purchase price back. A good reminder for anyone in the Holzer benefit print racket: the houses and the Hausers always win.

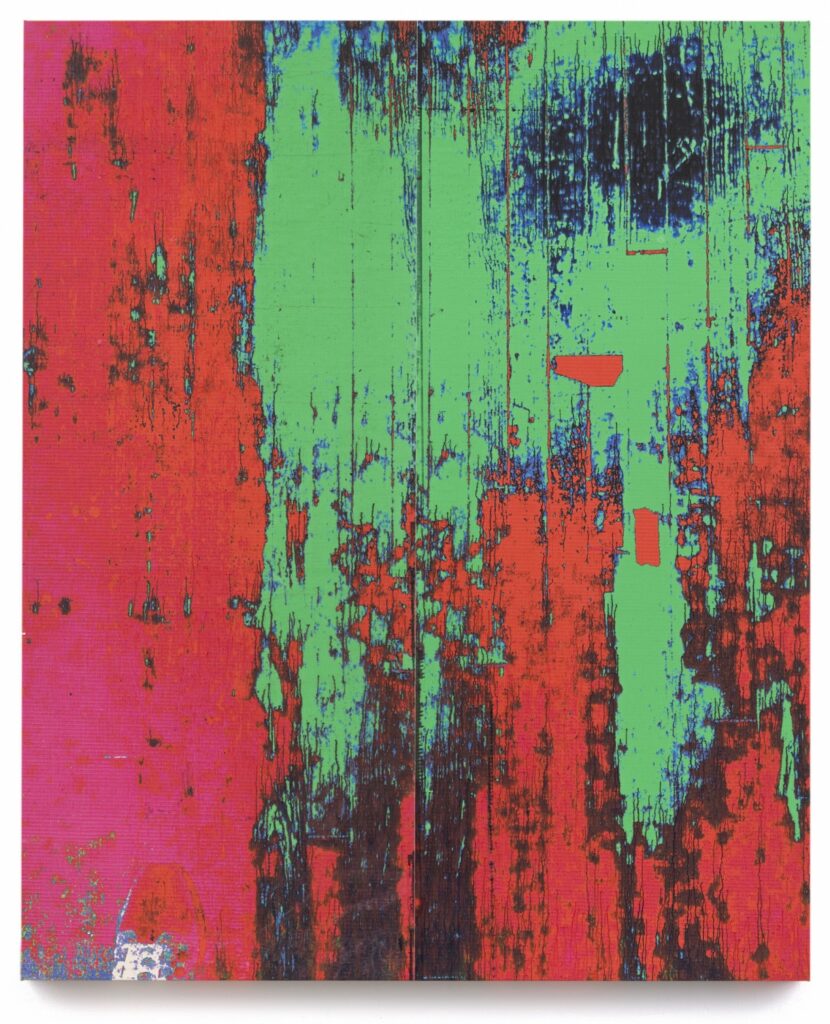

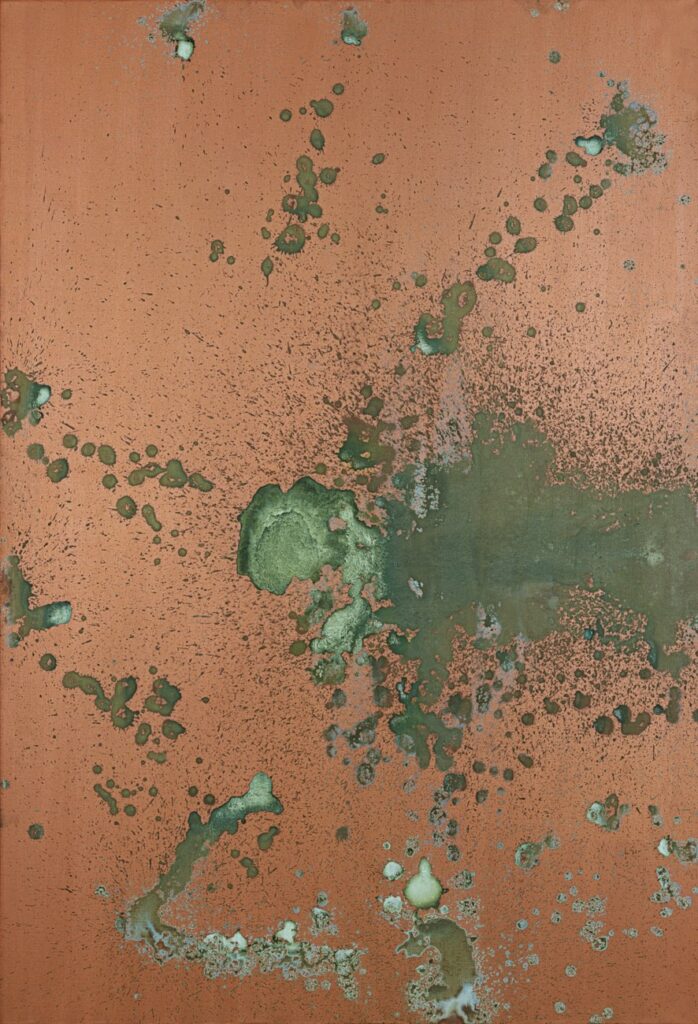

Don’t Piss On Me And Tell Me It’s Painting

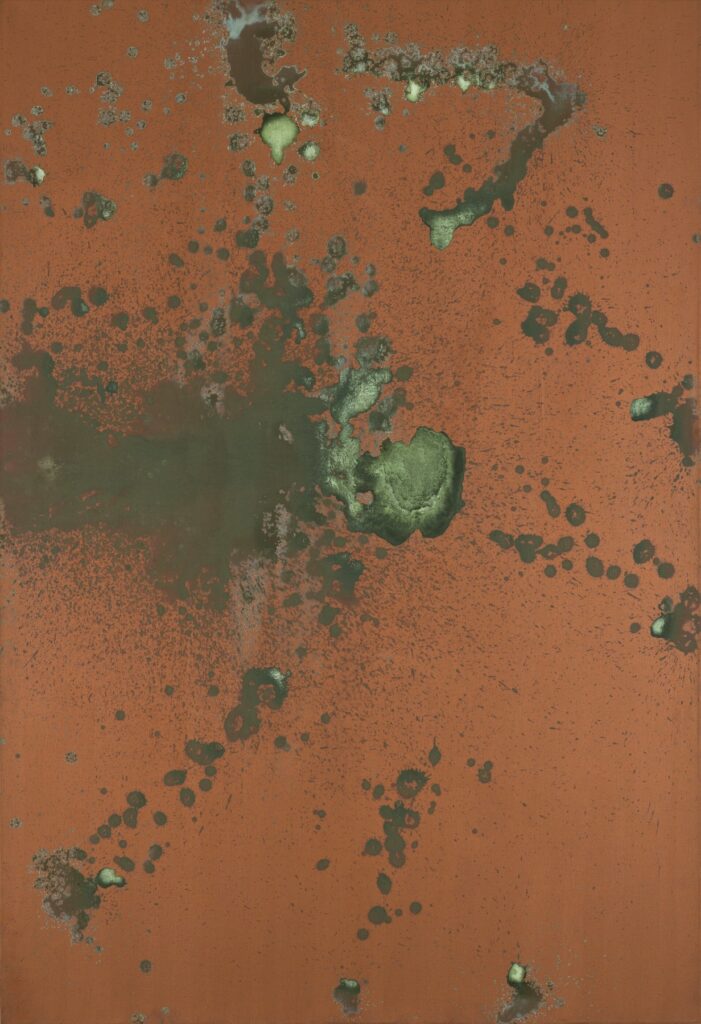

I’ve heard in the long run they stink, but then, so does Versailles. I do like Warhol’s Oxidation Paintings, though. I like how they went from Piss Paintings to Oxidation Paintings as their critical discourse expanded and their market value increased. How a taxonomy developed, where Piss Paintings are just the ones with piss on gesso.

I like how my sporadic attempts to research the Oxidation Paintings reveals that almost every piece of writing about them longer than a caption is the same. They use the same journal quotes about Ronnie Cutrone and vitamin B; the same Pollock, Duchamp, Mapplethorpe references; the same washed up comeback narrative, recovering from the same celebrity portraitist dismissals.

Is this all there is? Or is this all there is that keeps the market open and prices up?

Skarstedt has a show of Oxidation Paintings up right now in Chelsea that includes the painting above, which sold at Christie’s in 2008 for $1.899m, more than 50% above its high estimate. So I guess the text is working?

From the press release: “[The show] offers a glimpse into a moment when Warhol, often perceived as emotionally remote or mechanically detached, engaged with the most intimate forms of mark-making. And it reminds us that beneath the surface, there is always a question of presence, of process, and of transformation.”

Indeed, how were these paintings actually made? If it’s as straightforward as they seem, why did Warhol say it was so difficult? Do vitamins or other intake really affect the color outcome? Has someone tried to replicate these? And how does a painting made on the floor get a top and a bottom? Because Skarstedt is showing this one turned the other way, as Phillips did in 2022 .

[Morning after update:] greg.org hero Christian Oldham reminds us that Sturtevant had a great story about Warhol asking her to make one of his piss paintings, and she said, “Andy I don’t have the right equipment.” The rest I’ll leave to her.

Destroyed Donald Judd

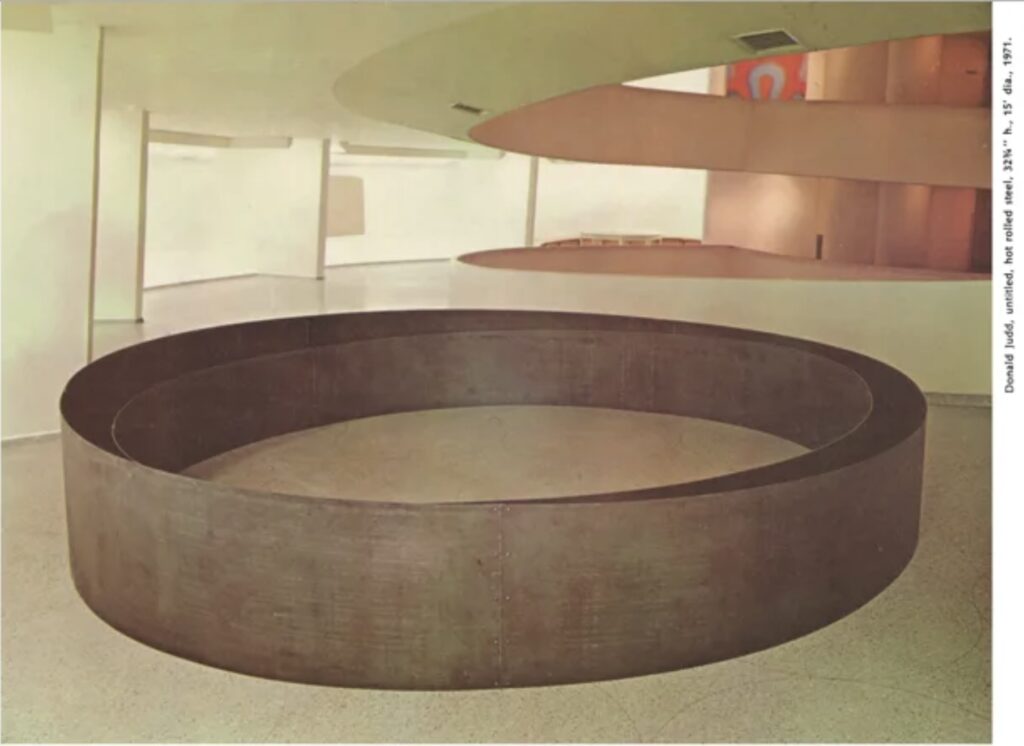

Donald Judd was extremely critical of the Guggenheim for, among many things, not buying art from him and other artists over the years. In 1990, around the time of the Guggenheim’s controversial acquisition of works from Giuseppe Panza, Judd wrote about participating in the Guggenheim International:

The one time that I’ve been involved with the Guggenheim is that for one mass exhibition I made a circular work of steel for the ramp in an attempt to deal with and acknowledge F.L. Wright’s architecture, which the museum itself is now desecrating, meanwhile, contrarily, expanding north and overseas. Despite my warning, this work was sold over a summer by Joe Helman to someone in St. Louis, who in passing on, passed it along to the Guggenheim, which evidently concluded that the work and the owner should remain together and stored it outdoors to irreparably rust. Years went by. Then last year Diane Waldman wrote that the museum wanted me to remake the piece. Well, the museum destroyed a work of art. Should the artist make good? I don’t want to have my work in Count (1940) Giuseppe Panza di Biumo’s Collection in the Guggenheim Museum and in its corporate departments of mass MOCA, Salzburg and Venice. I don’t share the attitudes back of this kind of behavior.

The 15-ft diameter work, above, comprised two concentric circles of steel. The inner one was of uniform height. The base of the outer circle matched the 3% grade of the Guggenheim’s ramp, and so the top appeared to be level. This discrepancy created an interesting tension and instability, even in an old photo. This image ran in an issue of Artforum with Richard Serra’s similarly round, steel, and site-specific work embedded in the pavement on 183rd St in the Bronx, on the cover. [Serra made it for the 1971 Whitney Annual.]

And besides the torqued ellipses, obviously, Judd’s sloped work also reminded me of a steel wedge Serra made for a ramp in what used to be a loading dock at Gagosian’s 24th St space. And the whole point of mentioning it here is that leaving the work outside to rot and then assuming the artist will remake it for you is almost exactly what happened with Cady Noland’s Log Cabin.

This circular Judd is not on the Guggenheim’s collection list at the moment.

40,000 Words By Or About Donald Judd

Donald Judd’s “Una Stanza Per Panza” is a fascinating, rambling, exasperated defense of the primacy of the artist in making and making decisions about his work, threaded through a fierce, bitchy, gossipy rant about the pomposity and presumptuousness of problematic and profiteering collectors. And dealers. And museums. Some museums. The ones who didn’t support working artists for decades, but who then give tens of millions of dollars to a collector who made grand, hollow promises to hoover up works on the cheap.

It was all driven by the years-long conflict with Giuseppe Panza over the terms for realizing artworks, sold by Leo Castelli as certificates or plans on paper. Judd’s understanding was that these were permanent, site-specific installations to be constructed under his supervision. Panza saw them as authorizations to make Judd sculptures when and where he desired, including making local copies for museums, and for sale. The evolving realization [sic] of how far apart these views of art were is a subcurrent of Judd’s 25,000+ word text. Though whatever his position at any given moment or paragraph, Judd never wavers in his own rightness.

Continue reading “40,000 Words By Or About Donald Judd”Johns In Paris

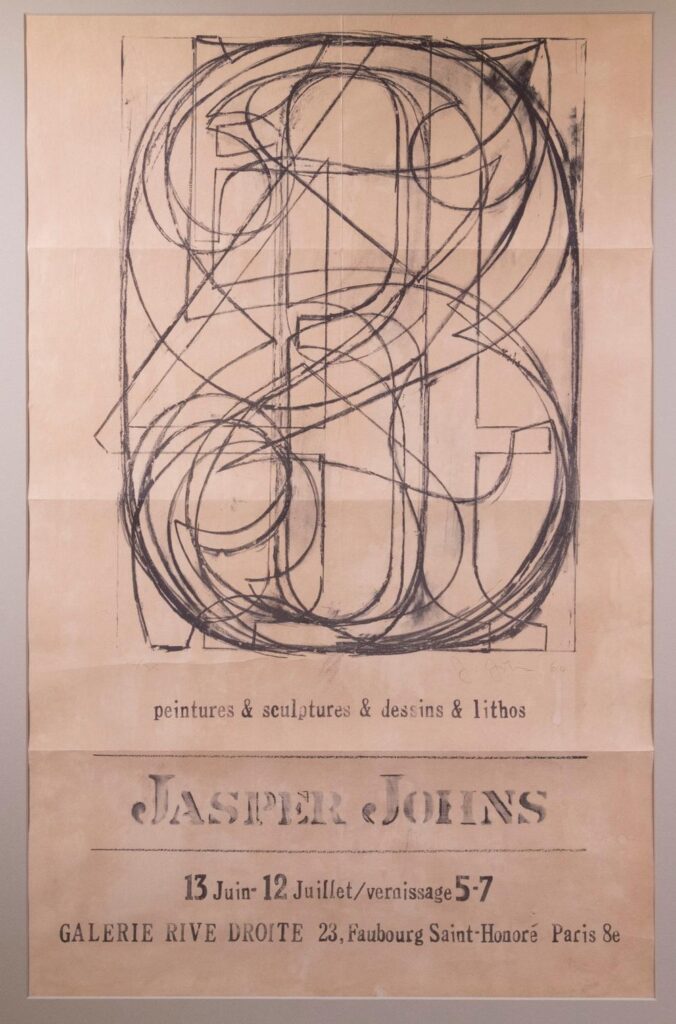

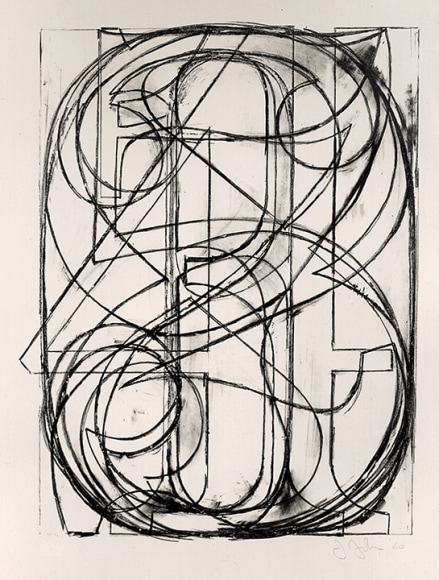

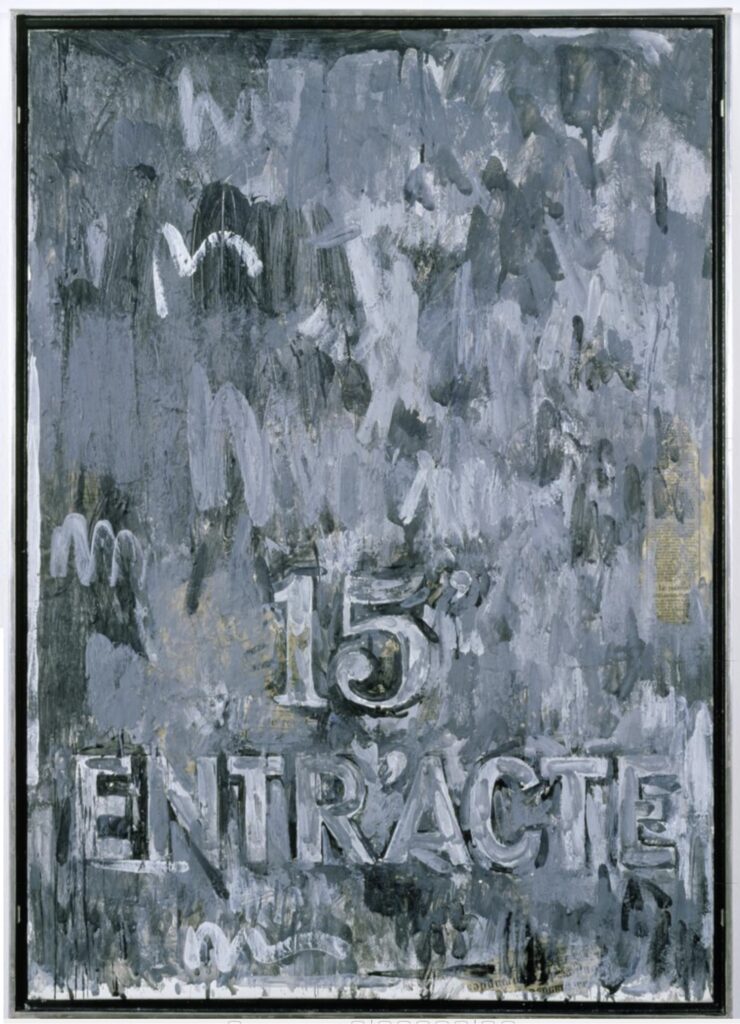

Even MoMA lists it as 1960, and they got their copy from the artist in 1961, so maybe. But the exhibition being announced here, Jasper Johns’s first show in Europe, absolutely took place in the Summer of 1961.

I get the confusion, though. Because the poster—most were actually mailers—reproduces a Johns lithograph, signature, date, edition number and all. 0-9 (ULAE 3), 1960, was published in an edition of 35. And whoever got No. 28 photographed it for this poster. Did the Galerie Rive Droite produce the poster, with Johns’s name in his already distinctive stencil? Or was it made in the US? That freeform accent over the Saint-Honoré makes me wonder. In any case, it has a nearly uniform handmade elegance that belies its offset print reality.

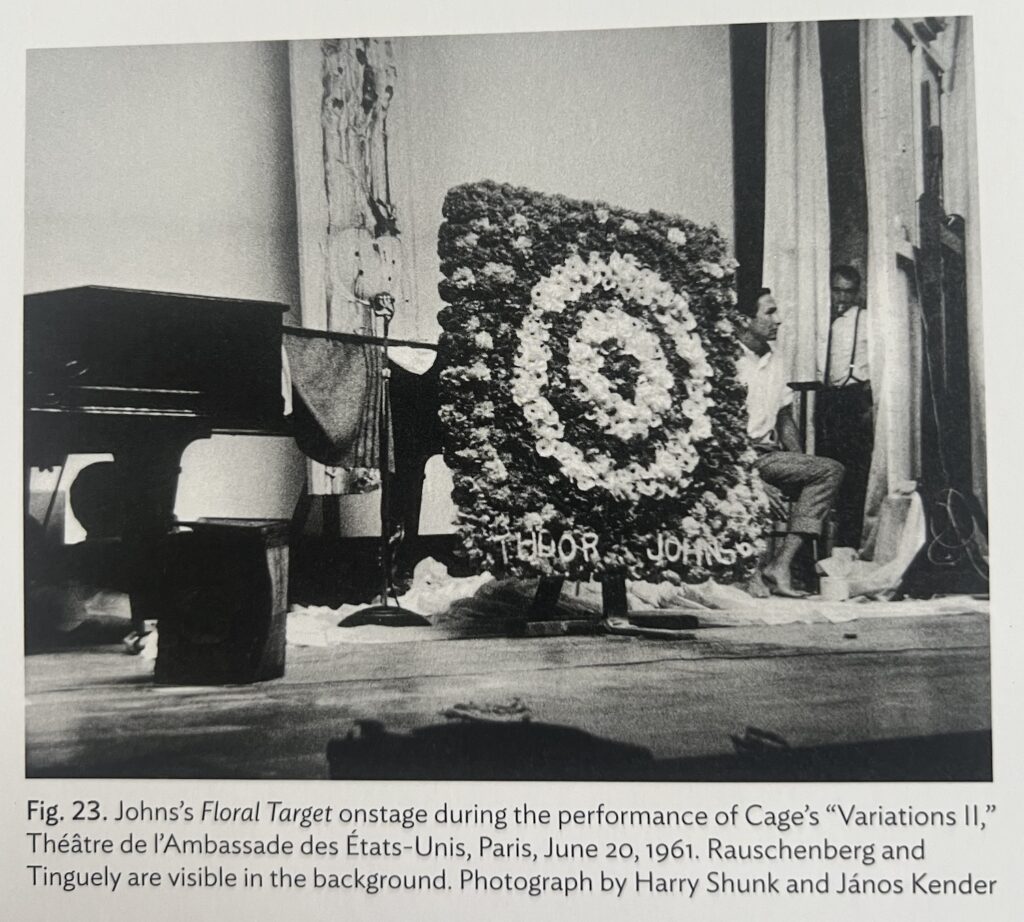

Galerie Rive Droite was around the corner from the US Embassy where, in the week after his opening, Johns, Rauschenberg, Jean Tinguely, and Niki de St-Phalle organized an art-filled performance for pianist David Tudor. June 20, 1961.

Johns sent flowers in the shape of a target* and whipped up a painting in the Paris studio of Alabamian ceramist Fance Franck. Though there was no actual intermission and the action never stopped, Entr’Acte was placed on stage for 15 minutes. Like the Sculp-metal 0-9 collage in the exhibition, Entr’Acte was bought by the secretary at Galerie Rive Droite, Georges Marci.

But was it really? To Google her now, Georges Marci shows up in the provenance of various blue chip artworks, is repeatedly called the “grand dame of contemporary art in Switzerland,” which has to be a self-anointed thing, and is known for opening the first gallery in Gstaad. But I guess people never thought the tapes would be made public, because in her 1974 oral history for the Archives of American Art, dealer Judith Richardson basically called Marci a thief who murdered her husband.

Richardson worked for both Sidney Janis and Ileana Sonnabend, Castelli’s ex. Which meant she worked with many overlapping artists with Galerie Rive Droite, run by Jean Lecarde. Lecarde wanted to open a gallery in Switzerland, and to get around the residency requirements, he transferred all the inventory to Marci’s name. And then she just froze him out and kept it, and he went bankrupt. This is how Arman tells the story, Richardson said. Arman was there, she said he said, when Marci set her depressed Egyptian husband up with the pills he used to kill himself. And then she got all his Coptic art.

Anyway, where were we? Johns found encaustic in Paris, borrowed a studio, and made this painting in like a day or two. While also finding time with Bob to shoot some paintings at St Phalle’s. Eric Doeringer just saw one at the Tate, shot by both Rauschenberg and Johns, and texted me about it. Turns out it was in St Phalle’s show that opened June 30, 1961. A busy summer in Paris.

Previously, related: The Performance Art in Embassies Program

* I have long wanted to see, then make, this flower arrangement, but I can’t remember where I’ve ever seen a photo of it. Somewhere, though. I’ll look.

In her MoMA retrospective, Leah Dickerman had a photo of Rauschenberg painting on stage while David Tudor played the piano. But she also said Johns carried his painting on stage to signal intermission, while Tomkins said Johns refused to go on stage. Both could somehow be true.

I knew I’d seen it somewhere. A closer look at Roberta Bernstein’s chronology shows Johns was booked and very busy in Paris: he made two plaster casts** in Tinguely’s studio; his costumes appeared on Merce dancers June 12; his show opened June 13; Tudor’s performance on the 20th; and he helped install Saint-Phalle’s show, which opened on the 28th. Also, what part of this itinerary did Shunk & Kender plan to be there for? Because it is amazing that they were around for an impromptu concert that came together in a matter of weeks.

** About those plaster casts: they were made from moulages made of the sculp-metal 0-9 and a similar Figure 3 from the Rive Droite show. So a 2nd generation cast. Which Johns used to promptly cast four more 0-9 in aluminum and, in 1997, four Fig. 3 in bronze. I low-key love that this feels like Johns wanting to keep engaged with works of his own that he expects not to see again, at least for a while.