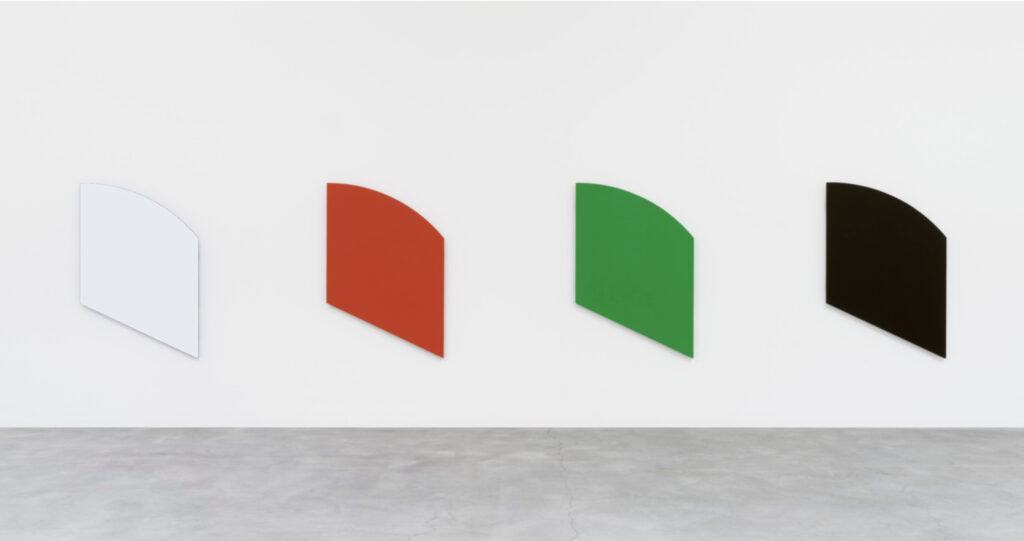

Posting about underseen little grey Richters really brings out the underseen little grey Richters. In a conversation begun on bluesky, Michael Seiwert mentioned seeing several in a very interesting show last Summer at the Hamburger Kunsthalle. Vija Celmins | Gerhard Richter, Double Vision, curated by Dr. Brigitte Kölle, is an intriguing Celmins show that is also a very rare two-artist Richter show.

I love the show’s idea of “juxtaposing such a strong female position with the work of Gerhard Richter, so often presented as a singular phenomenon,” not just to see his work “with a fresh eye,” but because it puts both of them in a larger, richer context. These artists clearly share interests, approaches, motifs, and even biographies, that felt unexpected at first, but feel obvious now.

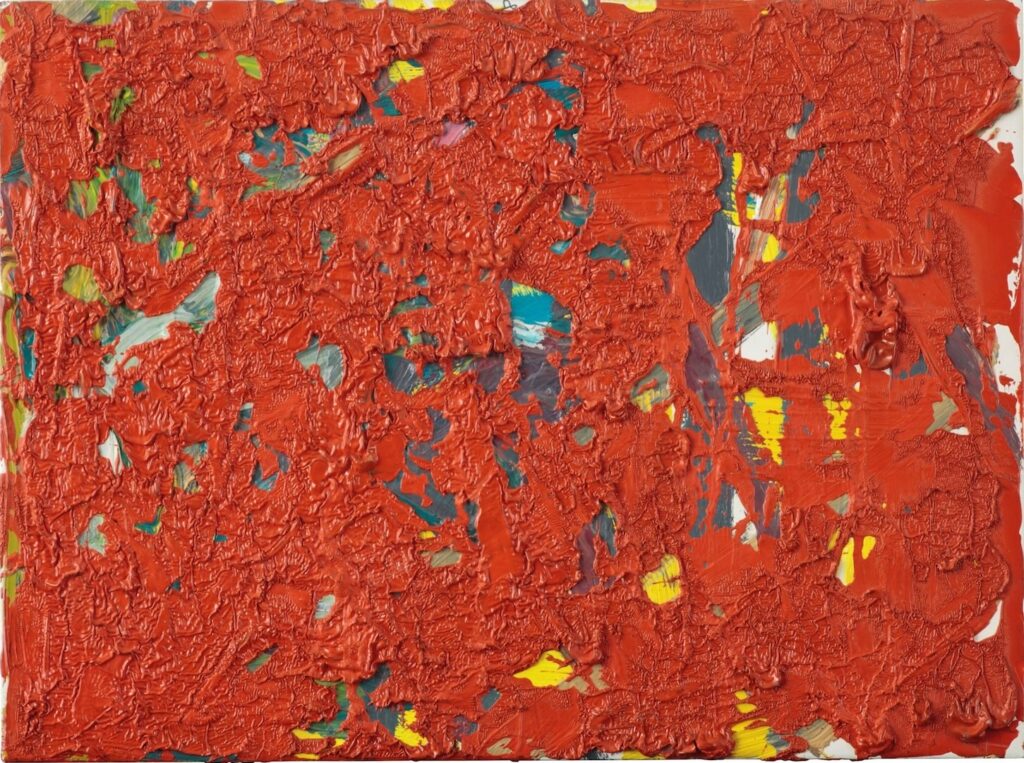

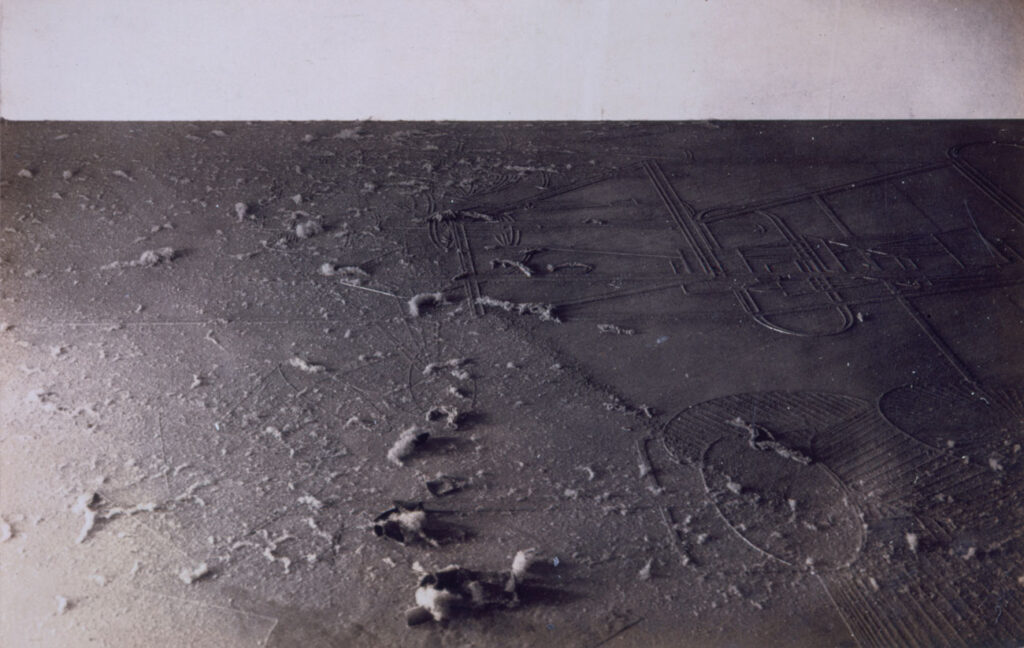

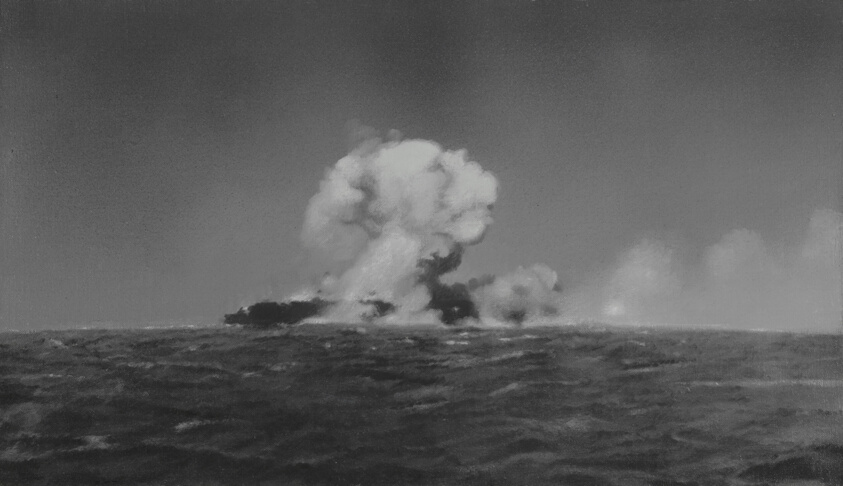

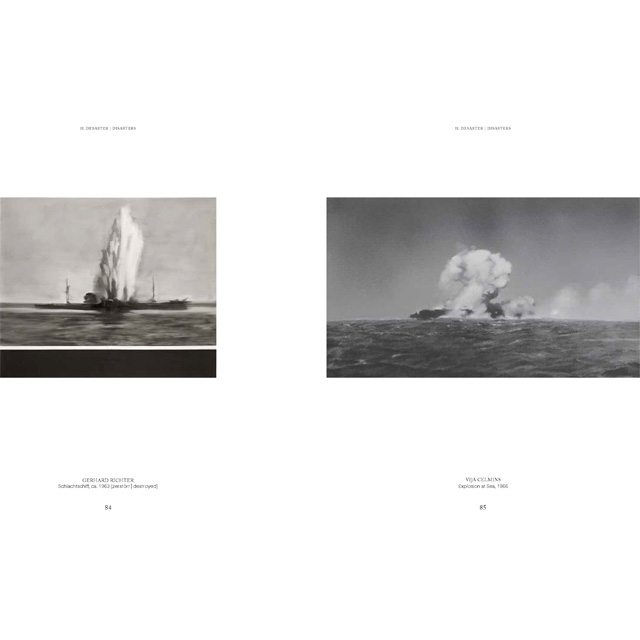

Some of the resonances between Celmins’ and Richter’s practices come immediately to mind: photo-based painting, found/everyday objects, seascapes, fighter planes, grey, they’re all in there. But browsing the catalogue, I was straight up surprised by the spread above, which features a 1963 Richter titled Schlachtshiff [Battleship], and a 1966 Celmins, Explosion at Sea.

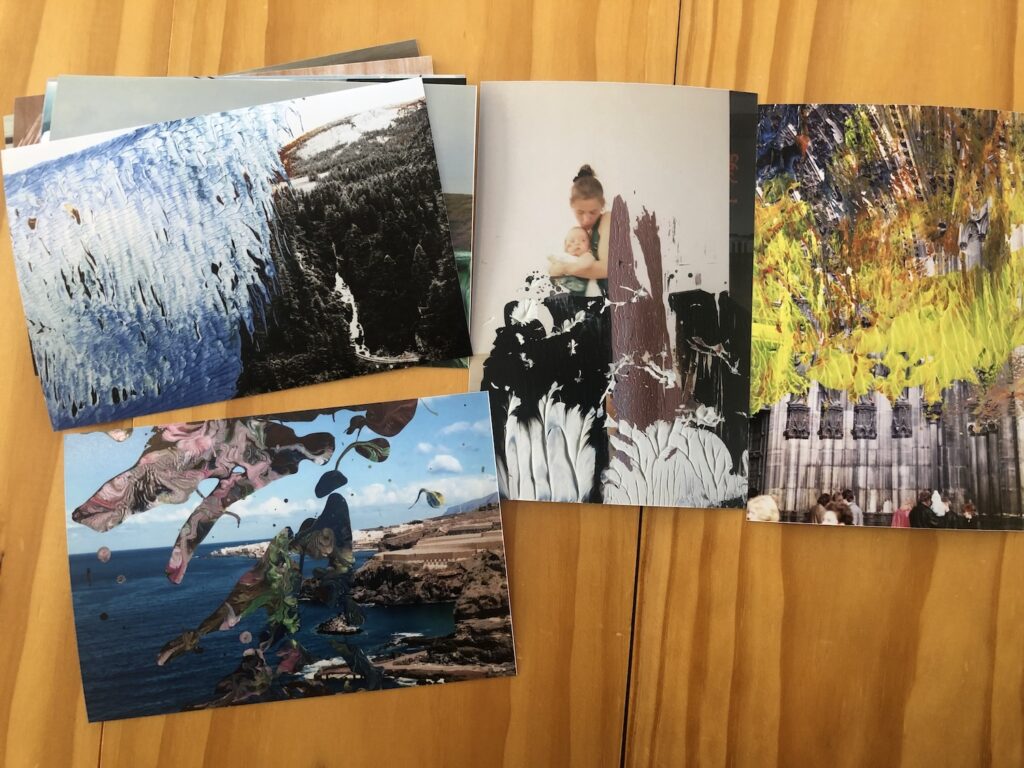

That Richter, though, is one the artist destroyed in the mid-1960s. It was the first of the Destroyed Richter Paintings I had remade in China in 2012, after seeing a photo of it, from Richter’s Archive, in Spiegel. OK, technically, and explicitly to the point, I had Richter’s archival photo painted at the scale of the destroyed painting it depicted, and I have shown and lived with this picture. So it is wild to see it included in this discussion. As Jaboukie might have said if he’d ever posed as Richter on twitter, “Just because I destroyed it doesn’t mean I can’t miss it.” Obviously, I am buying the book immediately.

Vija Celmins | Gerhard Richter, Double Vision, May-Aug 2023 [hamburger-kunsthalle.de]

Previously, related:

2012: Will Work Off JPEGs: Destroyed Richter Paintings

2016: Destroyed Richters at Chop Shop, as tweeted by Roberta Smith