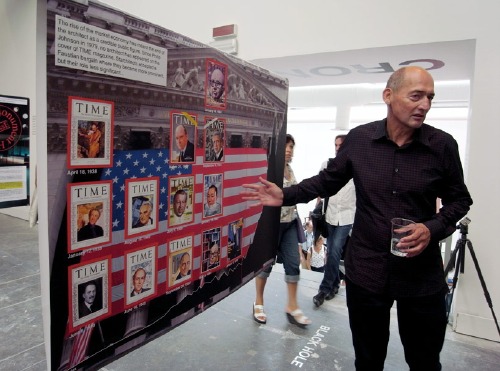

In the 1980s Daniel Libeskind was an increasingly prominent architectural theorist who–I was about to say “who had nevertheless not actually ever built anything,” but the whole thing that’s turning my head upside down is that he did, in fact, build something in the 80s: these machines.

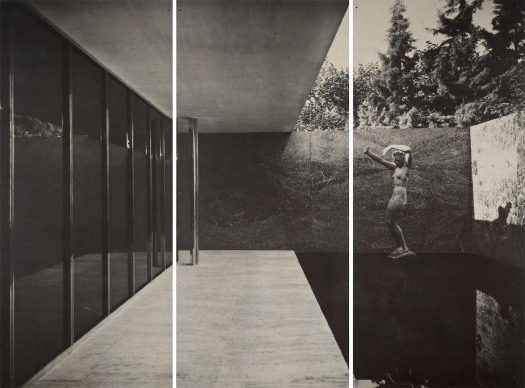

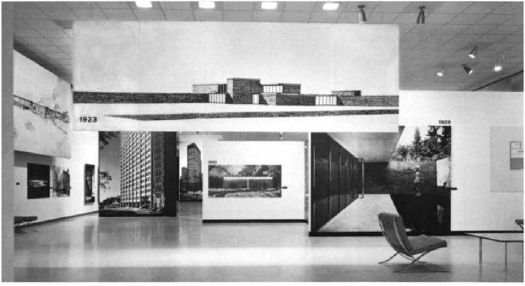

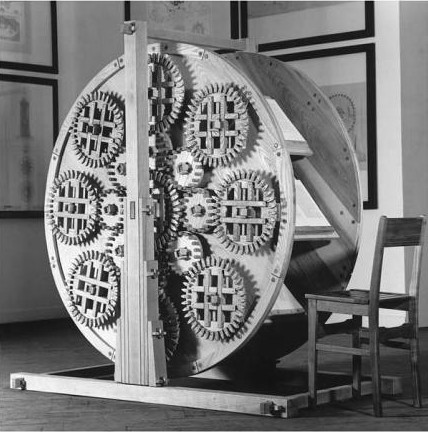

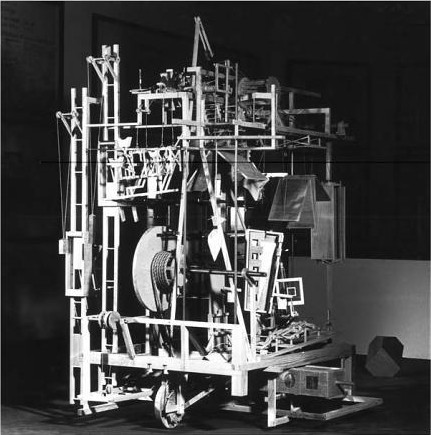

They were exhibited at the 1985 Venice Architecture Biennale as “Three Lessons of Architecture.” There’s The Reading Machine, The Memory Machine, and The Writing Machine, all intended as metaphors concerning the then-hotly debated post-structuralist theory of architecture-as-text.

Because I haven’t sprung for any Libeskind monographs where he discusses the project, for my understanding I rely heavily on Lebbeus Wood’s thoughtful blog post, which also happens to be full of beautiful photos of these incredible machines:

the vogue for a linguistic interpretation of architecture has passed, and the avant-garde has moved on, or at least elsewhere. Libeskind’s machines, inspired by reading and writing and implicitly interpreting texts, as well as memory (treated as text), would be of little interest today if the machines were only didactic illustrations of theory. But they are much more. As objects of design, they have powerful presence, as well as conveying a refined and highly rigorous aesthetic sensibility. As acts of the disciplined imagination of tectonic possibilities–how many parts might be assembled into a compelling whole–they are highly original, exemplary, and instructive. For example, in the diverse, even contrasting ways the same material, such as wood, can be used expressively in the same construction. Or, in the complexity of joints, from fixed to flexible, enabling the total assemblage. Of course, as hand-crafted constructions (a bit too ‘Renaissance’ for comfort, as was Tatlin’s Flying Machine), they are at once nostalgic and visionary, the latter if we believe that technology is not the main issue at stake in architecture

The ‘Renaissance’ feeling is not off the mark, and by design. To make his argument for the end of humanist architectural history and for a reincarnation of sorts for [his] universe of architectural reference points, Libeskind went way back, both in terms of design and technology, using period technique to build important unrealized machines from history.

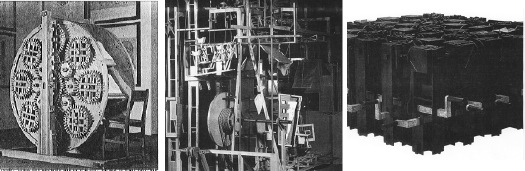

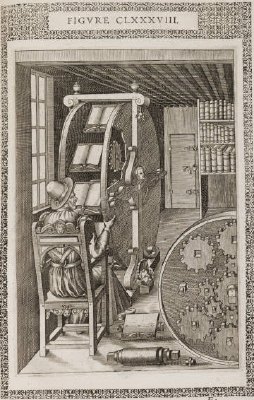

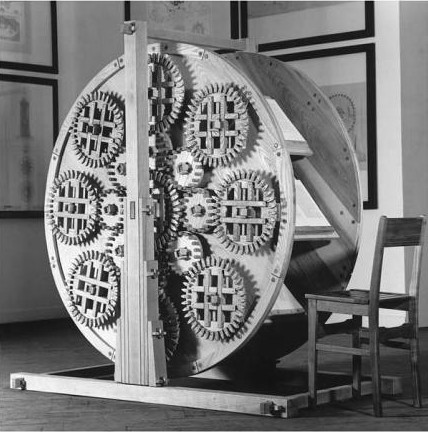

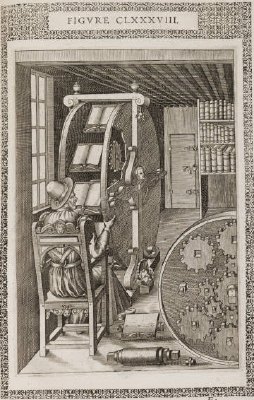

The Reading Machine, for example, is a fabrication of the “Reading Wheel” published in 1588 by Agostino Ramelli in his enormously influential engineering and design folio, Le diverse et artificiose machine del capitano Agostino Ramelli. It was designed to let a scholar keep his place while moving from tome to tome, a giant, creaking set of browser tabs. In a paper on “Three Lessons” presented in 2007, Ersi Iannidou [pdf] describes the making of:

Libeskind, determined to retrieve the experience of constructing such a machine, chooses to recreate not only the object, but also the experience. He works as a craftsman, bearing total faith in the craft of making. He builds it with hand-tools, solely from wood, with glue-less joints, dawn to dusk, in complete silence. When finished, he makes eight books–he writes them, makes the paper, binds them; just one each–and places them on the wheel. Each book contains just one word or phrase repeated anagrammatically: idea, spirit, subject, power, will to power, energia, being, created being…[it represents] ‘the triumph of the spirit over matter, of candlelight over darkness’. It teaches an ‘almost forgotten process of building’, namely, handicraft.

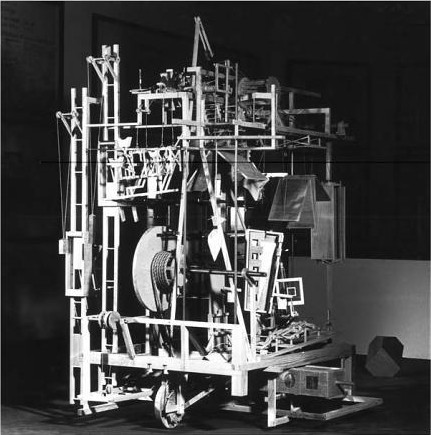

The Memory Machine is Libeskind’s interpretation of Giulio Camillo’s “Memory Theatre,” a 16th-century structure where, upon entering, a person’s mind would be filled and inscribed with a knowledge of the universe. Some historians have argued that Camillo’s idea influenced the construction of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre, which may or may not have been why Libeskind based his design on a period stage set apparatus.

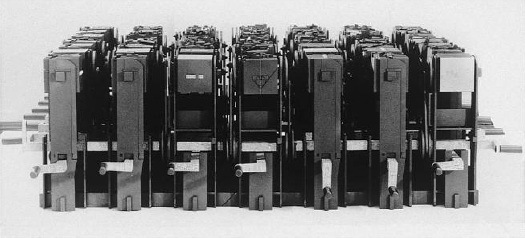

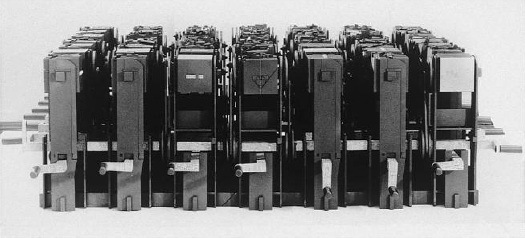

He makes a leap to modernity with The Reading Machine, which is an interpretation of Raymond Roussel’s “Reading Machine.” 49 square columns were rotated in impossible-to-follow ways by a series of handles, signaling the removal of the human architect from the industrialized city. Libeskind has since waxed, as he does, spiritually about the piece,

…which was designed to generate a new understanding of the ever-living city. This construction, a veritable spiritual experiment, involved reincarnating an experience of a medieval ascetic world, by constructing a machine in a monastic way, using no modern equipment, no electricity, but the discipline of craft, candlelight and the power of faith in the future text of architecture. The machine dealt with the organized chaos in which permutations of names of saints, both true and apocryphal, emblems, reflections and cities were symbolically and physically made mobile by turning the ‘circle into square’. It took twenty eight simultaneous rotations to turn the machine’s faces toward the unexpected image of a reawakened site.

Mhmm. Ioannidou quotes Libeskind as calling The Writing Machine “a quadripartite computer operation,” which begins to hint at at least one reference that I can’t find anybody making: to the difference engines of Charles Babbage, which were the early 19th century, mechanical ancestors of computers. Keep that in mind while reading Libeskind-via-Ioannidou again on the making of:

The Writing Machine is an industrial apparatus; so the architect becomes an industrialist, architecture a nine-to-five job. For the construction of this last machine Libeskind sets up a business, buys a clock, and focuses on the bare minimum of technique. He works hard–nine to five at the start, later overtime–speaks ‘small talk’, smokes cigarettes, does not mingle work with other issues–especially having fun.

I think we are to understand here that Libeskind not only built these things, but that he built them in deeply meaningful, experiential ways. They’re the not just by-products of his Method Architectural Theory, but its literalization. The Architectural Word Made Flesh. Or wood, as the case may be, but still.

As a guy contemplating the historically accurate bricolage-style refabrication of, among other things, a 1960 satelloon, I can appreciate all this seemingly conceptual performativity. Well, some of it. The part that isn’t a Renn Faire version of the Woodwright’s Shoppe. But the bigger problem for me is I’m not sure I like where this is heading.

Read Woods’ description of the seemingly unintended architectural consequences of post-structuralism’s decoupling of form and function and tell me that it doesn’t ft Libeskind’s disastrously clichéd building projects to a T:

What began as a radical concept affecting the very core of architecture, is compromised, we might say reduced, to commercially marketable and client-acceptable styles–a fate much the same as idealistic modernism suffered in its time.

So knowing what we know now, and faced with a worldwide blight of Crystalline Shard™ museum annexes and condos, can we see the warning signs of Libeskind’s epic failure in these machines? Are there other lessons to be learned from “Three Lessons”? Should I not let myself like these fantastical contraptions quite so much?

I don’t know yet. But it reminds me of the takeaway from 1939: The Lost World of the Fair, the book David Gelernter wrote while recovering from being attacked by the Unabomber, how we basically ended up with the future we were promised at the World Fair–including TV and car-based suburban sprawl–and it sucks.

On a more practical note, I’ve tried to find out more about the actual making of Libeskind’s machines, and to figure out where they are now. But since Libeskind’s studio only responds to “credentialed media,” I’m left to assume that all three machines met the fate of The Writing Machine, which Libeskind says was destroyed in a fire at the Palais des Nations Palais Wilson in Geneva in 1987. Too bad, because at the rate he’s going, they were the best things he ever built.