I’ve got a lot of browser tabs to clear before I head to Miami.

Am I not listening or looking in the right place, or is there really not enough discussion about MoCA’s exhibition of drawings by the composer/architect/polymath Iannis Xenakis?

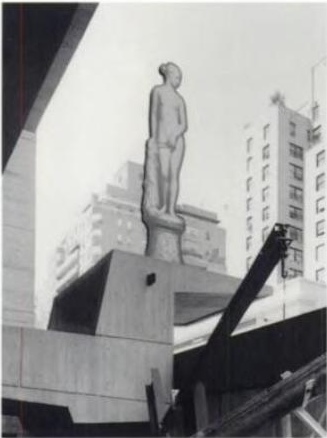

Xenakis was a longtime collaborator with Le Corbusier. Philipp Oswalt credits him with the introduction of light and projection as tools and “subject[s] of architecture” in the dramatic chapel of the convent at La Tourette.

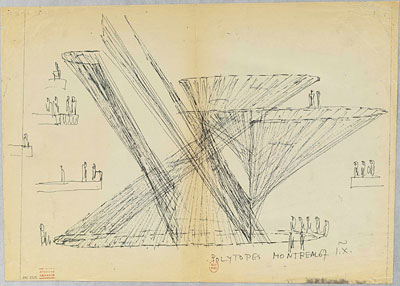

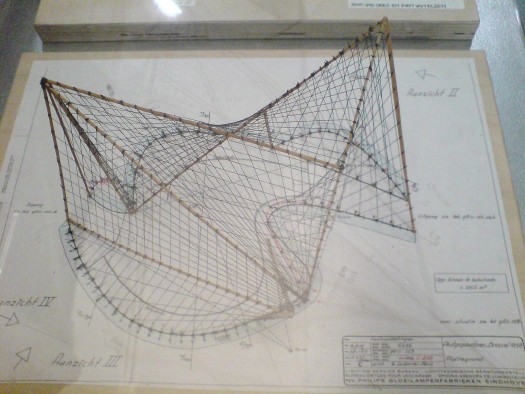

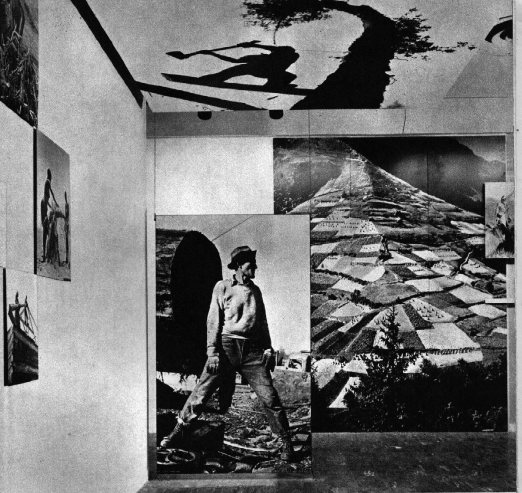

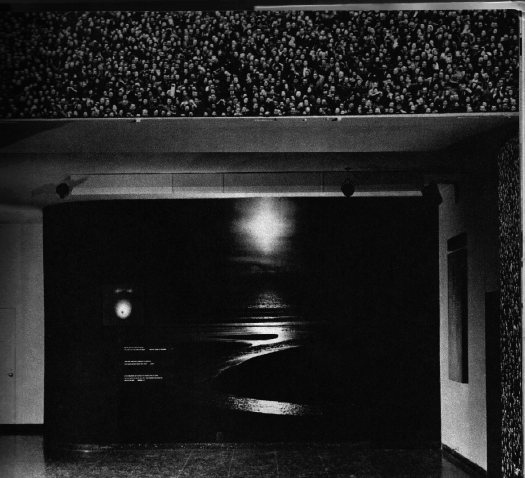

Tools which would come in handy in the multimedia Poeme Electronique, whose film projection cones and soundscapes drove the form of the 1958 Philips Pavilion [top].

Anyway, the drawings include musical scores, which sometimes appear interchangeable with Xenakis’ schematics and sketches for his later independent installations, including the Polytope for Montreal, above, an abstract light and sound environment, which he created around the time of Expo 67. The Xenakis archive is at the National Library in France. Not sure how accessible it is, but LA might be the best/easiest shot.

Related: Philips Pavilion models spotted in Amsterdam

Category: architecture

Jean Nouvel Should Build A Better Bedouin Tent

At least now we know what NY Times museum building critic Nicolai Ourossoff has been up to lately.

Just as I am thinking I need to add Saadiyat Island and the names of the grand new patrons of the arts from Qatar and Abu Dhabi to the greg.org art world pronunciation guide, I find a few things blocking my view of Our Glorious Cosmopolitan Future.

Since at least as far back as Rem Koolhaas bold, neo-Nixonian embrace of CCTV, a policy of architectural engagement has liberated our Western starchitects from the tyranny of conscience, of having to think or worry about the political or ethical unpleasantness of their state clients. I guess that exemption extends to our Western, liberal institutions, too–our Louvres, our Guggenheims, our NYUs, our Georgetowns.

But seeing as how I am not in one of these cultural oases and thus am not at risk of getting fired, deported, or arrested, I’ll just put some of the problematic parts in bold:

The consultant who works in fear of losing his/her job:

“There are religious extremists everywhere in the Middle East — even here,” said an Arab consultant who has worked on several developments and spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of being fired. The sheik, this person said, believes the cosmopolitan influences of the projects may help “open up the minds of these younger Emiratis before they go down that road.”

The international museum franchises walled off in hermetic playgrounds for the ruling class:

The new museums will be embedded in a kind of suburban opulence that can be found all over the Middle East, but rarely in such isolation and on such an expansive scale as in Abu Dhabi. The concrete frames of a new St. Regis hotel and resort and a Park Hyatt are rising just down the coast from the museum district, along Saadiyat Beach. Nearby, a 2,000-home walled community is going up along an 18-hole golf course designed by Gary Player, to be joined eventually by several more luxury residential developments and two marinas for hundreds of yachts. A tram will loop around Saadiyat, connecting these developments to the museums.

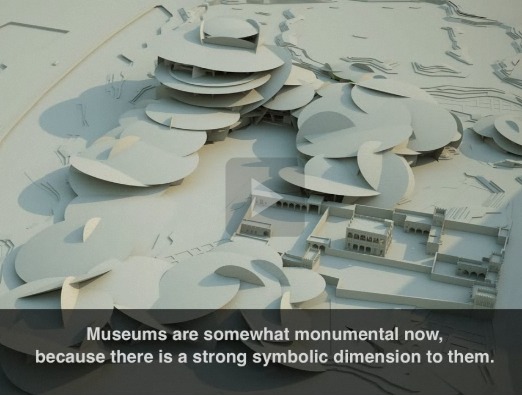

But wait, didn’t Jean Nouvel just say he’d “always wanted” to “make the museum part of the city, not just a building?”

The temporary workers’ paradise that doesn’t actually exist yet, except as a tourist stop for foreign reporters:

In some sense this village embodies a version of the cosmopolitanism Abu Dhabi says it is trying to create. But even if it is completed as planned, it will house only a small fraction of the city’s hundreds of thousands of migrant laborers; the rest will presumably live in cramped quarters in the city’s industrial sector or in faraway desert encampments. And once the museums are completed, a spokesman for the government development agency told me, it will be bulldozed to make room for more hotels and luxury housing.

And the kicker:

Even many educated Arabs in and outside Qatar — among the museums’ target audience — see a disturbing inconsistency in these grand plans.

“Some have lived here 50 years,” said Fares Braizat, a Jordanian professor at Qatar University who has been working on a census of foreign nationals. “They speak Arabic with a Qatari dialect, but they are still not allowed Qatari citizenship” or any of the enviable perks that go with it: free education and health care, interest-free government loans, preference in hiring, a sense of equality.

Here I would have to take issue with Mr. Ouroussoff’s characterization. Whatever feeling a Qatari citizen derives from his large, exclusive bundle of “enviable perks,” a “sense of equality” is clearly not among them.

But it’s not all bad. There’s something about Qatar’s National Museum that gives me hope:

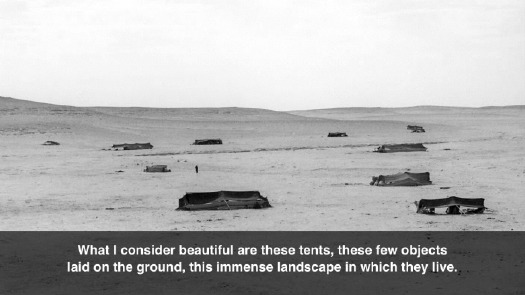

Inside, displays of tents, fabrics, saddles and other objects, as well as enormous video screens that will immerse the visitor in the experience of the desert, are meant to convey both the humble origins of Qatar’s royal family and the nobility of Bedouin life.

If we can get work through our tribalistic present, beyond both Qatar’s exploitative foreign worker practices and American jingoist sneers at the mere mention of Al Jazeera, maybe there will be a shared, globalized, nomadic future where the humble nobility of Bedouin life is celebrated as an aspirational ideal, not just an exotic throwback. Maybe a culture rooted in hospitality and mutual responsibility that subsumes, or at least reconciles the twin forces of rootless disconnection and nationalism which shape each individual’s worldview.

I’m not sure where billion-dollar museums shaped like falconry hoods or hyper-magnified sand crystals will fit in such a culture, but maybe that’s the point.

Building Museums, and a Fresh Arab Identity [nyt]

Why Enzo Mari Is Not Your Capitalist Art Market Stooge

Looking at objects and vintage photos in isolation, it blows my mind that Enzo Mari is somehow not a famous, formative artist, but only [sic] a designer. How did that happen? Did he make all his work in secret? Did he never try to show it? Did he just never sell it? Or enter an art dialogue? Did he get muscled out by Fontana and Manzoni for the parochial art world’s Seminal Sixties Italian Artist slot?

But you know what, he was a famous artist, or at least he showed his art for a long time in a series of prominent places, in exhibitions that were considered important and are now considered historic, even. And yet even as some of those events are being revived, revisited, and reemphasized, Mari’s involvement in them is not.

I was going to solve this mystery, and find the answer, using the two dozen or so browser tabs I’ve accumulated in the last 24 hours. But you know what, I think I’m just going to cut ‘n paste my links and let the info sort itself out.

Thing is, there probably ARE people who know exactly how or why Mari the Artist’s career or influence is the way it is; and it’ll be easier to try and track them down rather than engage in armchair speculation. Or I’ll just pigeonhole Hans Ulrich in Miami, either way.

So here’s what I’ve got:

Continue reading “Why Enzo Mari Is Not Your Capitalist Art Market Stooge”

Museumnacht At ARCAM, Or Greg.org: The Exhibit

When we last considered the techno-militartistic merits of pre-WWII era sound location devices, I wondered where to start. And now I know: the Netherlands.

When we last considered the techno-militartistic merits of pre-WWII era sound location devices, I wondered where to start. And now I know: the Netherlands.

I’m not sure why, but it was acoustic locator-palooza over there. On the wall of the awesome library in Stroom, the visual arts center in The Hague, I spotted a large poster of a guy sitting in a German-style portable locator. And there were two more images in Stroom’s recently published journal, Podium for Observation

Turns out they’re from the Museum Waalsdorp, which is located on a military base outside of The Hague. And apparently, they’re not German-style at all; they were designed in Waalsdorp in 1927 by an engineer named Ir.van Soest. And they have some there. But it’s only open on Wednesdays, and only with advance reservations.

In Amsterdam on Museumnacht, meanwhile, we headed from the Stedelijk to ARCAM, the city’s architecture center & museum, because their current exhibit, “Music.Space.Arch.,” sounded like I could have curated it myself. Or blogged it, more like:

The focus of the exhibition is the suggestion of space as created with the aid of acoustic objects. The spatial experiences relate to various scales, ranging from the intimacy of the individual to the spacious openness of the urban space.

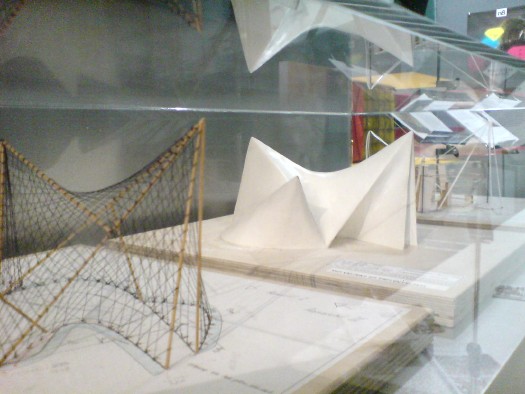

Included among the collected objects are the ‘Side Scan Sonar’, which brings the urban space surrounding ARCAM to the visitor, and listening equipment with which enemy aircraft were detected in the Second World War. With ‘Sound Scrape Shoes’ by Ricardo Huisman, the ARCAM building becomes the source of the experience, while in the presentation of the famous Philips Pavilion of 1958, the proportions are completely different from what we are familiar with.

Acoustic locators AND a re-creation of the Philips Pavilion? How could we miss?

Well.

We literally arrived at ARCAM one minute after the tap dancer had begun her show. Now for me, tap dancing is to real dancing what rhythmic gymnastics is to real gymnastics, or what synchronized swimming is to swimming: an over-aestheticized mutation that is somehow unaware of its own awfulness. And that’s on a good day.

When you have a Dutch punk tap dancer–an alternative tap dancer, in a country where they probably have a Bureau of Alternative–in tasseled pants, dancing in the dark while an assistant shines a flashlight on her shoes, whose “intimate interaction” with ARCAM’s building basically meant pushing the entire contents of the exhibit into the corner so she could erect her hollow tap floor, it is really unforgivable and unsalvageable. And that’s even before the audience participation segment began.

So we stayed in the corner, where the “completely different” proportions of the Philips Pavilion re-creation turned out to mean three A2-size models borrowed from the Atomium. Fantastic, but tiny. That wireframe’s especially nice.

But the projection on the exterior of the museum of Le Corbusier, Xenakis, and Varese’s Poeme Electronique, considered to be the first immersive multimedia environmental installation, had been turned off, another casualty of the evening.

Oh, and there on a pedestal, behind some people’s butts and under their coats, was a real live Van Soelst acoustic locator. Only it wasn’t from Museum Waalsdorp; it was from somewhere else entirely: the Wings of Liberation Museum in Best. Holland must be the most acoustically located country in the world right now.

And so as we left behind a slightly chaotic-seeming jumble of awesome objects brought together by an amorphous, subjective theory, I realized that the only way to tell this blog apart from a multi-million-euro art, architecture & cinema center is that I’m the one without a tap dancer.

Cage, Yoga, Museumnacht At The Stedelijk

The last time we were in Holland for a Museum Night, it was in Rotterdam, and it was an infuriating mess. All the museums in the city stay open until 2AM and program special activities and events. In 2005, that included an impromptu drum circle on and around some large Donald Judd sculptures in an unattended wing of the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen. When the one guard I finally found wouldn’t do anything to stop it, I went to the front desk and demanded to see the director–who showed up, and finally closed the lower floor.

So yeah, a bit incredulous, but Museumnacht Amsterdam turned out alright. We started at the Temporary Stedelijk, which had, not guards, but actual bouncers at the door, so it stayed very civilized the whole time we were there. They’re in the second half of a major construction project, so the renovated galleries were sparsely populated by works that didn’t need much, if any conservation or climate control. And many of the galleries were just plain empty.

And it was utterly fantastic. It felt like having the entire museum to yourself.

The ersatz yoga studio in Barbara Kruger’s installation was amusing, but the most interesting thing was a performance by members of the contemporary chamber orchestra, Ives Ensemble, of a 1987 John Cage piece, Music For…(1984-87). The composition, for “variable chamber ensemble,” has parts for up to 17 instruments [each titled, Music For _Clarinet_, _Violin_, &c.] and can be performed by from one to seventeen musicians, who are to be scattered throughout a space.

It was created for an ensemble in Pittsburgh, but I didn’t write down the details from the score, figuring [wrongly] that I’d be able to find out more online.

Anyway, the performers–there were six in the version we saw, and they said another member of the ensemble would join them for the two later performances–synchronized their stopwatches while standing on the dais for On Kawara’s One Million Years A.D. [which was off, the empty seats making me think about hopping up there ourselves and just rattling off numbers, for fun], and then they hustled off to find their rooms.

There were a couple of doorways where you could see two performers at once, but mostly, you’d see one, and hear a couple of others bleeding through. We did about three laps of the piece in around 30 minutes. There were probably a couple of dozen active listeners scattered about, and then another couple of dozen folks who we only saw once.

I was initially skeptical of the National Gallery’s decision to play Morton Feldman’s Rothko Chapel in their all-black Rothko installation in the Tower Gallery, but I quickly softened, and the last two times I’ve been there, it’s been a transformative pleasure to be all alone in that space for 20-30 minutes at a time.

Hearing Cage’s work filter through a museum was equally rewarding, and it made me want to experience more of it. I spoke with a few musicians afterward, and they were practically giddy; it was apparently a surprising and fascinating experience for them, too. Which means it’s rarer than museum yoga.

‘Nylon Airhouses’ By Frank Lloyd Wright

I’m thinking I might have to change the name of this blog to Holy Smokes, but holy smokes, did the past ever look more futuristic than it did in the pages of LIFE Magazine, November 11th, 1957?

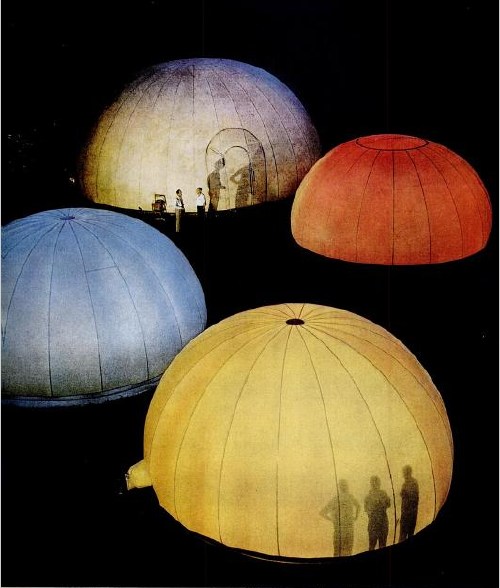

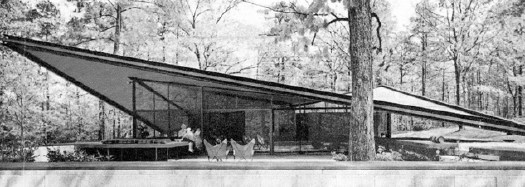

That’s where I found the house of the future of the past, Eduardo Catalona’s Raleigh House, in the issue titled, “Tomorrow’s Life Today – II.” There’s also THE Monsanto House of the Future from Disneyland. There’s an Alcoa aluminum beach cabana thing; the cover’s got a transparent, inflatable pool dome; a three-generation family of mimes, I guess, laying around in black leotards on a candy-colored assortment of foam slab furniture. And then there’s this:

Nylon Airhouses pop up on a university campus in Kentucky. Made of U.S. Rubber Company’s Fiberthin, a vinyl-covered nylon fabric four times as strong as waterproof canvas yet 40% lighter in weight, domelike houses are kept up by air, pumped in by small motors. They are anchored at base by a ballast ring of sand or water…

According to Sean Topham’s Blowup: Inflatable Art, Architecture & Design, this “Fiberthin Village” or “Rubber Village” of airhouses was designed by none other than Frank Lloyd Wright.

Actually, according to Billboard, US Rubber was manufacturing the warehouse-sized airhouses, but the domestic-scale models were being produced by the Irving Air Chute Company of–aha–Lexington, KY. Now that you mention it, they do look rather parachutish.

But why is Billboard reporting on repurposed military technology? Because in the summer of 1957, airhouses were competing against an international chain of “balloon bijoux” for the right to stage concerts in Central Park. What’s “most appealing” about these inflatable concert venues, we learn, is that they promised “the virtual elimination of large crews of roustabouts to set [them] up.”

In 1961, The Rotarian reported that, in addition to U.S. Rubber–which also introduced Keds, by the way, in 1917–a major player in the growing inflatable dome building industry was G.T. Schjeldahl, who also fabricated the Project Echo satelloons. See, it all comes back around.

Eduardo Catalano’s Raleigh House

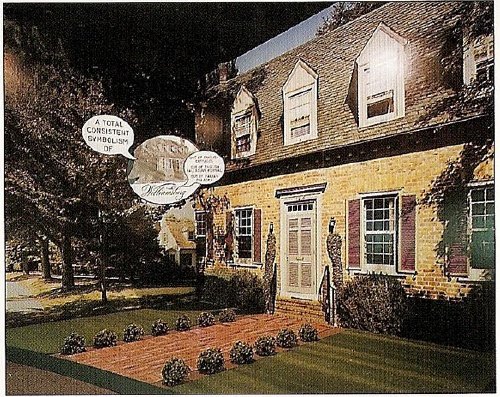

I couldn’t really articulate it at the time, but the overwhelming absence of modernist architecture was an integral part of growing up in Raleigh, North Carolina. The country roads were widened, and winding capillaries and cul de sacs were cut into the pine forests on either side, which were given ever more oblique English-sounding names, and whose lots were promptly filled with tens of thousands of Colonial Williamsburg knockoffs.

But I did date a girl in high school who lived in an early 70s, wood-clad, contemporary-style house. It was just off of Ridge Road.

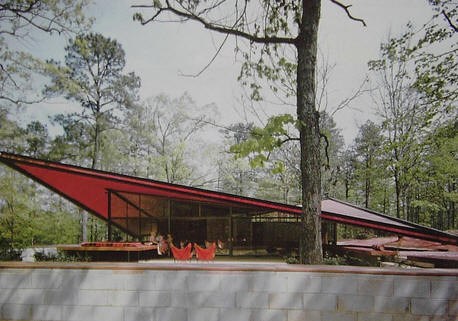

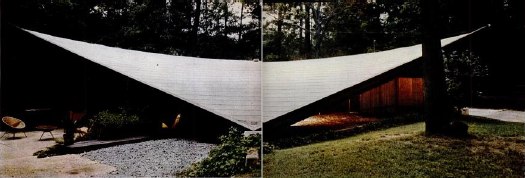

Just off of Ridge Road was also where the Argentine-by-way-of-Harvard architect Eduardo Catalano designed himself a house in 1954, when he came to teach at the just-founded School of Design at NC State. How did I never go to this house?

Catalano’s house was an 1800 square foot glass box underneath an absolutely stunning 3600-sf hyperbolic paraboloid roof which, holy crap. It’s, well for one thing, it was Wolfpack Red.

LIFE Magazine called it the “Batwing House” in 1957, and noted that “the shape makes it possible to have a thin roof with great structural strength [apparently, thin meant just 2.5 inches. ed.]. It is supported on the ground at only two points. Catalano is now trying to arrange mass production of its roof in aluminum instead of costly laminated wood strips.”

Aluminum? How about poured concrete? That’s what Le Corbusier and Iannis Xenakis built the striking paraboloid peaks and folds of the Philips Pavilion out of at the 1958 World Expo in Brussels. How quaint of Brussels and Corbu, to be only 3-4 years behind the architectural innovations of Raleigh, North Carolina.

But Williamsburg will out. Catalano left for Boston in 1956 and sold what he always called the “Raleigh House” to some locals. Who sold it to some people who rented it. Who sold it to a guy who asked Karl Gaskins, the architect who, it turns out, designed my HS friend’s house, to design an addition, which was never realized. And who abandoned it behind chainlink fencing for six years so it could rot. That was from 1996 to 2001, exactly the miniscule window of time when the last vestiges of my intention to move back to North Carolina “someday” overlapped with my own dotcom bubble. When no saviors could be found, the house was razed and the lot divided for two McMansions in 2002.

And Catalano spent the last eight years of his life trying to have his Raleigh House roof, at least, re-created, maybe at the NC State Museum of Art? At the garden of his former school, NCSU? At the former, he was politely rebuffed. At the latter, he faced a surprisingly vocal opposition from professors in the landscape design department.

To these pine tree-pushing philistines, I say, “Whatever.” And I will add Catalano’s house to the list of Things I Want To See, And So Must Rebuild.

Triangle Modernist Houses has the whole happy/sad tale of Catalano’s masterpiece, and a bunch of photos [trianglemodernisthouses.com now usmodernist.org]

The Wound Dresser, Set In Stone

I’m feeling more serious about turning Richard Neutra’s Cyclorama building at Gettysburg into an educational monument to the wounded and a wheelchair-accessible battlefield observation platform.

War becomes history, reduced to its most basic contours, a date, a bodycount, and a winner:

Future years will never know the seething hell and the black infernal background of countless minor scenes and interiors, (not the few great battles) of the Secession War; and it is best they should not. In the mushy influences of current times the fervid atmosphere and typical events of those years are in danger of being totally forgotten.

…

The present Memoranda may furnish a few stray glimpses into that life, and into those lurid interiors of the period, never to be fully convey’d to the future. For that purpose, and for what goes along with it, the Hospital part of the drama from ’61 to ’65, deserves indeed to be recorded–(I but suggest it.) Of that many-threaded drama, with its sudden and strange surprises, its confounding of prophecies, its moments of despair, the dread of foreign interference, the interminable campaigns, the bloody battles, the mighty and cumbrous and green armies, the drafts and bounties–the immense money expenditure, like a heavy pouring constant rain–with, over the whole land, the last three years of the struggle, an unending, universal mourning-wail of women, parents, orphans–the marrow of the tragedy concentrated in those Hospitals–(it seem’d sometimes as if the whole interest of the land, North and South, was one vast central Hospital, and all the rest of the affair but flanges)–those forming the Untold and Unwritten History of the War–infinitely greater (like Life’s) than the few scraps and distortions that are ever told or written. Think how much, and of importance, will be–how much, civic and military, has already been–buried in the grave, in eternal darkness !……. But to my Memoranda.

That’s Walt Whitman’s foreword to his Memoranda During the War, a compilation of his diary entries, which he published in 1875.

In a country at war, so seemingly polarized by political disagreements, it’s odd how easy it is to forget that not only was there a civil war, there was an aftermath, where millions of Americans had to put their lives, their families, their cities, and their country back together again. Is forget the right word for something you presumably knew, or should have known, but really never gave a thought to?

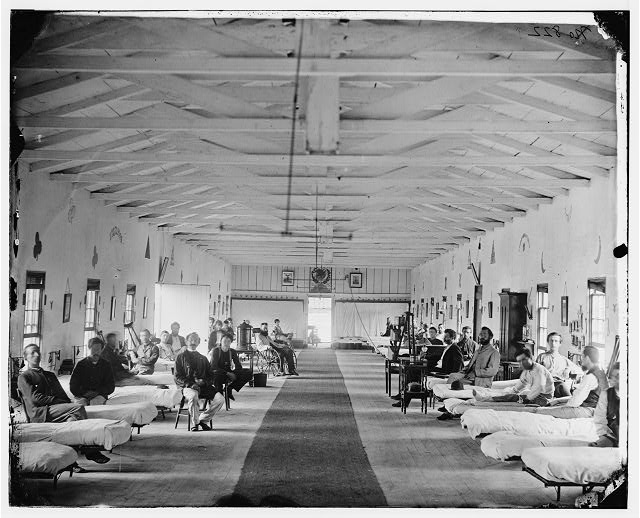

Armory Square Hospital, 1865, via loc.gov

Because I didn’t forget so much as never realized, never put it all together, that the wartime hospitals, where I knew Walt Whitman attended to wounded and dying soldiers, were not in Brooklyn, where the Whitman in my mind lives. They were in Washington, DC, where he’d come looking for his brother George, who’d been wounded in the battle of Fredericksburg. He stayed on, and tended over 80,000 men who belonged to what he called, “The Great Army of the Sick”:

June 25, (Thursday, Sundown).–As I sit writing this paragraph I see a train of about thirty huge four-horse wagons, used as ambulances, fill’d with wounded, passing up Fourteenth street, on their way, probably, to Columbian, Carver, and Mount Pleasant Hospitals. This is the way the men come in now, seldom in small numbers, but almost always in these long, sad processions.

Whitman also visited the hospitals at the Patent Office [now the Smithsonian Museum of American Art] and at Armory Square [above, now the site of the National Air & Space Museum]. His compiled letters to his mother, published in 1897 under the title of an 1863 poem, The Wound Dresser, contain additional details of his experience.

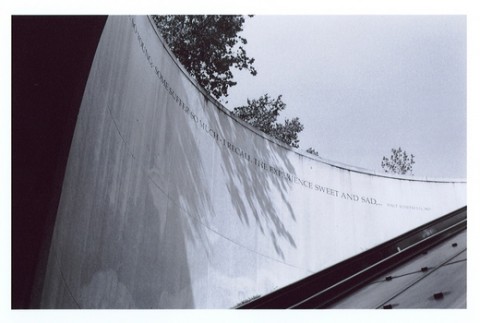

awesome torqued circle image by marc nielsen via flickr

Originally published as “The Dresser,” the poem is the centerpiece of Drum Taps, Whitman’s collection of war-related poems first published in 1865, and included in subsequent editions of Leaves of Grass, beginning in 1867.

A stanza of “The Wound Dresser,” or at least part of one, wraps around the cylindrical granite wall of the entrance to the DuPont Circle metro station:

Thus in silence in dreams’ projections,

Returning, resuming, I thread my way through the hospitals;

The hurt and wounded I pacify with soothing hand,

I sit by the restless all dark night – some are so young;

Some suffer so much – I recall the experience sweet and sad…

– Walt Whitman, 1867

New York carpetbagger and infrequent DuPont metro traveler that I am, I’d always assumed it was installed in the early 90s, an oblique sop of acknowledgment of the AIDS crisis. Ahh, yes and no.

The idea for the poems did originate with a community request to “honor those who cared for people with HIV/AIDS,” [2025 update: internet archive link] but this had been expanded to include caregivers for all kinds of illnesses. And so the D.C. Commission on the Arts and Humanities sponsored a competition for poems as part of the Metro’s Art in Transit program. In 2007.

One would think that a 150-year-old poem by America’s greatest poet could survive a seemingly routine governmental agency arts collaboration unscathed. But I guess the public art doctors felt they must amputate to save the patient. With the last two stanzas cut off the inscription serves as an inadvertent memorial to what must still be sacrificed to make a permanent mark on the official landscape of 21st century Washington:

(Many a soldier’s loving arms about this neck have crossed and rested,

Many a soldier’s kiss dwells on these bearded lips.)

For much, much original Whitman material and even more Whitman scholarship, visit The Whitman Archive [whitmanarchive.org]

Next, related: Toward a Cyclorama-shaped Gettysburg Memorial to The Wounded

Art Is Where You See It: YouTube Play @Guggenheim

Though I had considered entering, and I’d sampled a few of the 125 videos on the shortlist, I had planned to not write about the YouTube Play Biennial at the Guggenheim. But then reps from a couple of the event’s sponsors, HP and Intel, asked if I’d guest post about art, video art, and film in their Facebook group, 24|7 Creative, and they invited me to attend the big gig at the Gugg last week. Here is a brief recap of that experience, and how I see it.

[Holy smokes, this is long now, really, unbelievably long. And with a tragicomic surprise ending, too!]

Continue reading “Art Is Where You See It: YouTube Play @Guggenheim”

Observations On/From Towers

Last May, while solving the problem of Gettysburg and reuniting the opposing forces of History–Civil War battlefield aficionados seeking to “restore” the “hallowed ground” of Cemetery Ridge and the modernists and historical preservationists who wish to stop them from demolishing Richard Neutra’s Cyclorama building–I myself was smitten by the archival/architectural awesomeness of the steel observation tower [below], which was built by the War Department in 1895 on the [equally hallowed, I’m sure] Confederate line.

[My idea, of course, is to adapt Neutra’s ramp-centered structure into a disabled/wheelchair-accessible observation platform, an accommodation which is sorely lacking in the current Park Service program for the site, and then to integrate a museum/memorial to the tens of thousands of soldiers wounded–and disabled–in the battle. We’re so quick to memorialize those who were lost, while forgetting or ignoring those who survived, and have to grapple for the rest of their lives with the effects of war.]

Anyway, two added pieces of information:

While I have not been able to find much in the way of history or documentation for the 1895 towers [there used to be five; now there are 2.5], I have discovered two accounts of a re-enactment of Pickett’s Charge in July 1922, on the occasion of the 59th anniversary of the battle. On July 2 President Warren G. Harding and his wife observed a rehearsal re-enactment by 5,000 marines and veterans from an observation tower [since removed] on Cemetery Ridge itself.

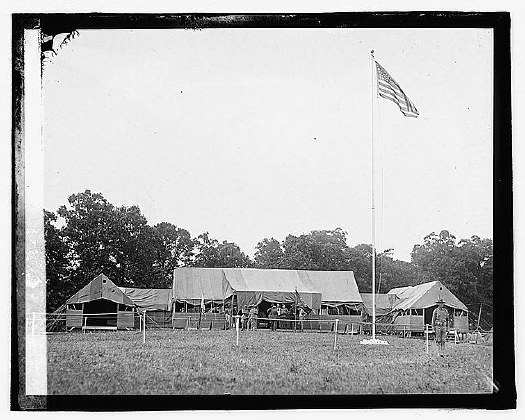

[Bonus architectural note: The President and Mrs. Harding were quartered at the Marine camp in what the New York Times called, “a temporary White House of canvas and wood. The structure is equipped with elaborately fitted sleeping rooms, baths, electric lights and even has a front porch.” A search for photos has already begun. update: and may be over. Is this it, from the LOC?]

Another account, dated July 4th, after the Hardings had departed, comes from Mrs Helen Longstreet, the widow of the Commander of the Confederate forces at Gettysburg. It’s not clear, but I like to imagine that she observed the re-enactment–“staged today with marvelous accuracy in every detail, exactly as I have heard General Longstreet describe it hundreds of times”–from the still-extant observation tower on the field:

As the twilight of this calm July day deepened into dusk I overtook one of “Longstreet’s boys,” a one-armed veteran, trudging wearily “up Emmitsburg Road.”

“Where did you lose your arm?” I inquired. He answered: “In Pickett’s charge; and it was powerful hard to lose my arm and be whipped, too; and what was the use of it?”

Someone standing near pointed to the Observation Tower and said: “Do you see the flag that floats up there? The stars on its blue field are all the brighter, its red stripe all the deeper, its white stripe all the purer, because you left an arm in front of Cemetery Hill in Pickett’s charge. That was the use of it. That was the good of it.”

And so the tread of marching armies and the roar of cannon over the Summer lands of Pennsylvania call the American people to express the value of the titanic struggles of the ’60s in deeper love and pride of country.

And the other thing, holy moley, have you seen the observation tower built by the Graz/Munich-based landscape design firm Terrain in a nature preserve along the Mur River in Styria, Austria?? 27.5 meters high, double rectangular spiral of black steel and tension rods, plus aluminum staircases.

Not that I thought anyone might be wavering on the architectural merits of observation towers or anything, just, wow.

[images: just two of many at Abitare]

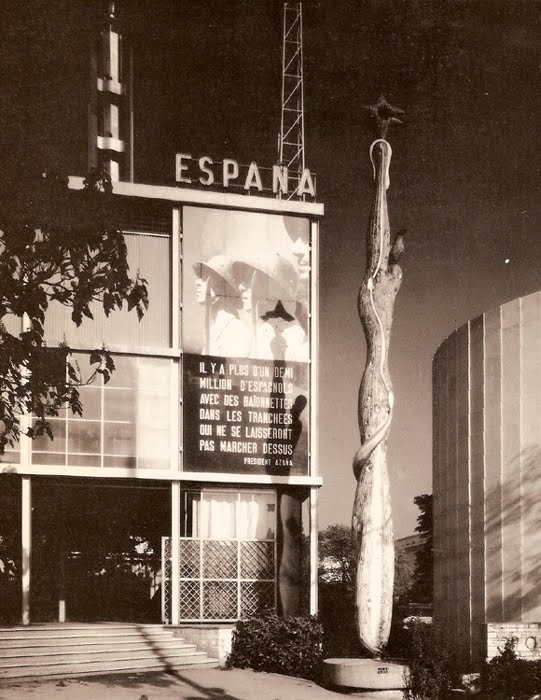

¡Pasarán In! The Spanish Pavilion, Paris 1937

Worlds Fairs turned out to be the perfect venue for photomurals–they were catchy, usually didactic, packed a visual punch, and got the point across to the shuffling masses. And at least in the 1930s, they looked like the future.

So to a government whose future was being immediately threatened, like the Spanish Republic under siege by Franco and his fascist army, a publicity- and sympathy-generating pavilion at the 1937 Paris Expo literally seemed like a matter of survival.

José Luis Sert and Luis Lacasa designed the small, simple pavilion, which didn’t get completed in time for the opening, and which anyway, ended up being overshadowed by the bombastic, dueling pavilions of Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia.

So to get attention, a huge photomural/banner of Republican loyalists was hung over the entrance. [Intriguingly, in two of the three most widely circulated photos from the Expo, including the Le Monde photo announcing the opening, the mural is cropped out or coincidentally obscured by a tree branch.] As kk_redax’s photo on flickr shows, the photomural was changed periodically:

Like breakdancing was to gangs, world’s fairs were designed as a non-violent means for competitive, conflicting nation states to jockey for supremacy. But the Spanish Civil War pushed the Republican government to a new, urgent level of pavilion-building. The war, which was fought on the ground through media, posters, photos and newspapers [and also guns and bombs], also gave birth to modern photojournalism. And the Paris Expo was the site of Spain’s immediate experiement in architecture as military polemic. And then there’s the art.

The Republican government sought to garner international support by assembling modern works by sympathetic artists that express powerful and overt political outrage, including a large painting of an upraised fist by Joan Miro . And unveiled on the ground floor was Picasso’s Guernica.

Painted in 24 days in his new Left Bank studio in the spring of 1937, Guernica‘s duotone palette reflects how Picasso and the rest of the world learned of the Nazis’ devastating saturation bombing foray: via newspaper photos and newsreels. Photography had an even more direct impact on the making of Guernica: Picasso asked his companion Dora Maar to document the painting process, and there’s a scholarly case that “the tonal variations Picasso observed in Dora’s photographs appear to have influenced the development of those in the middle stages of the painting.” Though it sets the bar pretty high for the rest, it’s not much of a stretch to call Guernica the greatest photomural of the 20th century.

But wait, that’s not all! In the Pavilion Guernica was installed next to Mercury Fountain, an abstract, kinetic sculptural tribute to the Almaden region of Spain, which at the time produced the lion’s share of the world’s mercury. Oh, the fountain was by Alexander Calder. While Guernica‘s world travels are well known, Mercury Fountain is a Calder whose relocation was both successful and imperative. It currently sits at the Fondacion Miro in Barcelona, sealed behind glass, in order to contain its toxic vapors.

Guernica, meanwhile, is now encased in glass for its own protection.

…The Spanish Pavilion [pbs.org]

A comprehensive post about El Pabellon Espanol, in Spanish [stepienybarno.es]

The Mexican Suitcase, rediscovered Spanish Civil War negatives by Capa, Chim, and Taro [icp.org]

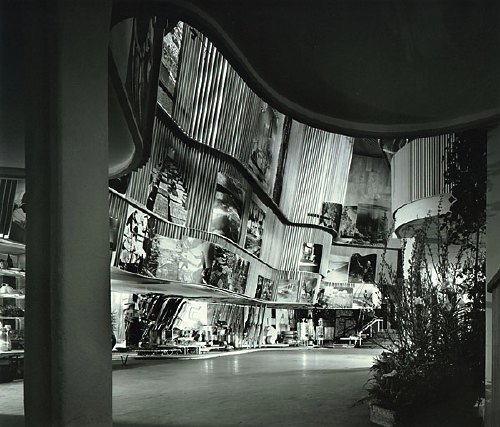

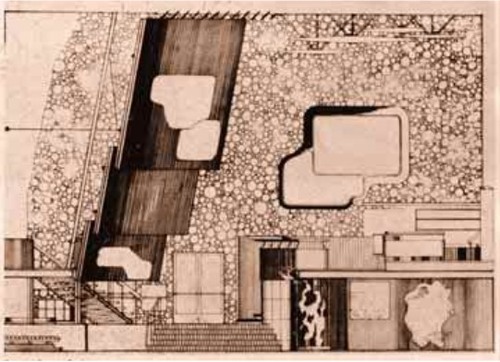

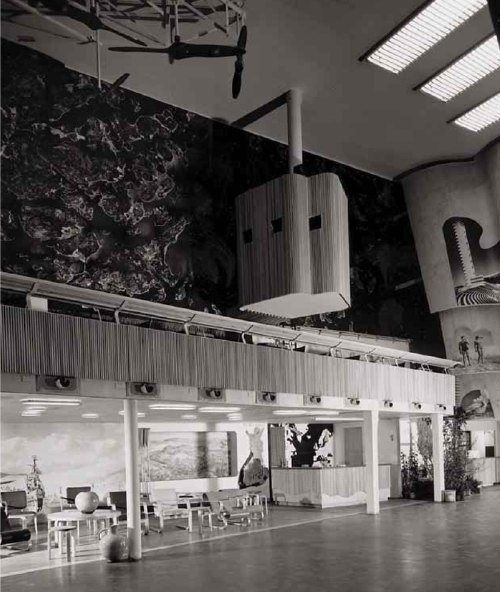

The Enlarged Pictures Generation: Alvar Aalto’s 1939 Finnish Pavilion

image: vintage silver gelatin print, signed, Ezra Stoller, 1939, via morehousegallery

Do turning back another chapter or two in the history of enlarged pictures, photomurals, and photomontages, where do they turn up the most [besides/before the Museum of Modern Art]? Expos and World’s Fairs. Even more than dioramas, and like the grand cyclorama paintings of earlier eras, giant photos were used by architects–in the service of governments and companies–as modernist, machine age, marketing, mass communication, and propaganda. They were basically highly credible-looking billboards.

None of which is necessarily a bad thing in itself, of course. It’s interesting to note, though, who was creating and using them, because for the most part, it was not artists.

Alvar Aalto’s Finnish Pavilion at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York turns out to have been a stunning and especially instructive example of enlarged photos integrated with modernist architecture. That’s it up top in a photo by –let’s just say I could just as easily title this whole series, “Everything I Know About Photomurals, I Learned From Ezra Stoller.”

In a plain, rectangular building, Aalto wrapped a second floor exhibition space with an undulating wood-slatted wall, inset with three rows of giant photos [Aalto’s section plan above, via domus, I think] to create a dramatic, infotaining, 52-foot high atrium. A mezzanine restaurant [below] allowed for closer viewing of the photos, which showed, from top down, “Country,” “People,” and “Work,” which culminated, naturally, in the bazaar of real Finnish products underneath.

And what’s that box up there hanging dramatically off the wall, besides the key to the photomurals’ media context and appeal? It’s a projection booth. Films, presumably on the subject of Finland’s awesomeness, were projected onto the atrium wall above the exit. I can’t help but see the effectiveness and popularity of large-scale photos as inextricably driven by architects’ attempt to harness the modern media magic of the cinematic experience. And as antecedents for the now-ubiquitous, immersive projection and installation art works. Like steampunk Pipilotti Rist.

1939 Finnish Pavilion info [designboom]

The Family Of The Family Of Man: Steichen, Miller, Rudolph, Stoller…

I’m on a bit of a photomural binge at the moment. In email, Dr. Olivier Lugon, he of the awesome article about Stephen Shore’s Signs of Life photomurals, points out two things about Edward Steichen [and, let’s give the man credit, since he’s all over and in that show, Wayne Miller, though with these brackets, where do I put the apostrophe s?] ‘s 1955 show, The Family of Man.

First the good news: The sole [?] remaining copy of the traveling version of The Family of Man was donated to Luxembourg, the country of Steichen’s birth, and it is on permanent display at Chateau Clerveaux. Except that it just closed two weeks ago for two years, for renovation and conservation. So, book your post-Maastricht2012 roadtrips to Luxembourg now!

Now the bad news, which is also good news: The installation photo I linked to purporting to be from The Family Of Man is, in fact, not. It is from a 1945 exhibition Steichen did at MoMA titled Power In The Pacific, which was designed by George Kidder Smith.

I say good news, though, because it pushes the photomural story back a decade, and it helps flesh out the context and function of enlarged photography as a mass communications, i.e., propaganda tool. Power In The Pacific was comprised of photographs taken by the Naval Aviation Photographic Unit, which was under the command of Capt. Edward Steichen, and which included Lt. Wayne Miller. Ansel Adams would have been in there, too, but he wanted to delay enlisting for a couple of months, and Steichen wouldn’t have it. Adams went on to photograph the Manzanar Japanese-American internment camp, photos of which were exhibited at MoMA in 1944. [Now those are some photomurals I’d love to see. Except, well, let’s put that in another post.]

Power in the Pacific opened in January, while Steichen was still on active duty, and traveled around the country. [I did not realize this until just now, but Steichen reported to the head of the Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics, Rear Admiral John S. McCain, Sr. Small world.] Many of the Naval Unit photographers’ work was included in Family of Man.

Which, I just couldn’t resist scanning in a couple of Ezra Stoller’s magnificent photos of Paul Rudolph’s installation from the original Family of Man catalogue.

photos by Homer Page, Brassai, George Silk (on ceiling)

photo by Pat English used as wallpaper framing an unknown landscape.

As seen in Stoller’s photos, Rudolph’s show is an apotheosis of the enlarged photo and mural as an architectural element, a maker of spatial experience. It’s easy to say that photomurals and photomontages are architecture, or marketing, or propaganda, and not art, and it’d be true. But it’s also true that photography itself was not art at the time, either. As for photomurals and giant, painting-sized photos, they were merely the things exhibited in the Museum of Modern Art.

Stephen Shore’s Photomurals, I Mean, ‘Architectural Paintings’

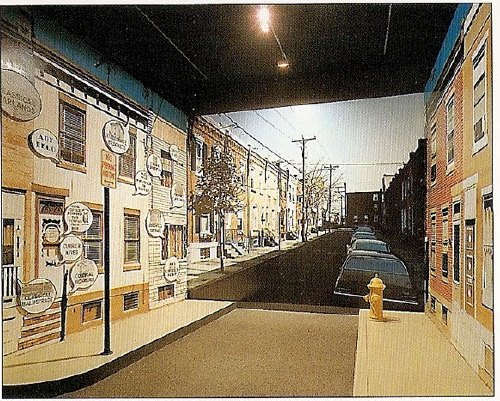

that sidewalk, that exit sign, that door. installation image of Stephen Shore’s images, 1976

So yes, I’ve got a million other things to do, but thanks to this Mies thing being auctioned, and Michael Lobel’s article on photography and scale–and by implication, photography and painting, pace Chevrier’s forme tableau–I’m become slightly obsessed with the history of photomurals.

From what I can tell so far, I have the field largely [sic] to myself, but there is definitely some interesting work out there–and some interesting writing about it. And who should turn up as one of the innovators of these scale-blasting photomurals, but the master of the snapshot himself, Stephen Shore?

Just this past May, Swiss art historian Olivier Lugon published an article in Études photographiques titled, “Before the Tableau Form: Large Photographic Formats in the Exhibition Signs of Life, 1976.”

Signs of Life: Symbols In the American City was a groundbreaking and somewhat controversial show held at the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery as part of the US Bicentennial celebrations. Conceived in 1974 on the heels of the publication of Learning From Las Vegas by Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour, it was, depending on who you asked, an exultation, an examination, or an elitist excoriation of commercial and populist vernacular architecture and design. They filled the gallery with iconic roadside signs, and they created dioramas of archetypal American living rooms to give all Our Stuff the museological treatment.

And to photograph it all–and to create giant, deadpan photomurals of the American residential streetscape–Izenour selected a young photographer whose seemingly unstudied roadtrip snapshots had just been shown at the Met, Stephen Shore.

Lugon quotes Venturi & Scott Brown’s explanation of the show [I’m translating back here from French, so it’s probably off a bit]:

“The idea was to cross the model of the billboard, this image made for distant, fugitive, distracted perception of the driver, with that of the newspaper, which is a density swarming with information.” The art museum is thus invaded by two different but interdependent media regimes: the advertising billboard’s principle of rapid distraction, and the extreme informational concentration of the newspaper, two opposing models for aesthetic contemplation, where the distance of the viewer from the image is either too far or too close.

Despite working at like 100x his previous [and, for the most part, subsequent] scale, Shore’s illusionistic photo backdrops manage to capture the banality he loves. Banality in a good way, of course. I think this street is my favorite:

Maybe because he wasn’t a fetishy print guy–Shore rather famously sent all his film to Kodak to be developed, just like civilians–he readily embraced the print quality of the photomurals. Which–I love this–turned out to be paintings.

Lugon explains that the Signs Of Life photomurals were made with an expensive, state-of-the-1976-art, 4-color airbrush-like printing system from the Nippon Enlarging Color Company, which had been licensed for the US by 3M. Who marketed it to trade fairs and restaurants as Architectural Painting. With the public and art world attention from Signs of Life, 3M brought Izenour on to promote the new medium for use by artists and museums.

In 1977, Popular Science ran an article explaining how Architectural Painting technology worked. A specially prepared color negative was scanned and split into CMYK, and the quick-drying paint was applied in overlapping strips, inkjet-style, by a computer controlled, scanning sprayer. 3M technicians then touched up the finished print by hand. All in, it cost $10-25/sf.

Expensive enough to be the second largest line item on Signs of Life‘s budget, and sexy enough that Venturi et al. used it again almost immediately. For their controversial [i.e., steaming hot mess, according to Robert Hughes, who I’ll happily believe just this once] exhibition design for the Whitney’s Bicentennial blockbuster, 200 Years of American Sculpture, the architects installed a 27-foot-tall cutout photo by Shore of Hiram Powers’ iconic marble, Greek Slave, on the canopy of the museum. Ezra Stoller says it was “inspired by Caesar’s Palace,” which I’m sure was a compliment:

Once again, I start programming a bonus DVD for “The Original Copy,” Roxana Marcoci’s current show at MoMA on photography and sculpture. But I think the real story here is painting and photography.

Jean Francois Chevrier gets credit for the term forme tableau, which he used to describe the large-format photographs which began to assert a place on the wall and in the discourse that had previously been reserved for painting in the 1980s [and since]. Then Lugon mentions how Sherman, Prince, Kruger, etc. had appropriated the photography of commercialism–advertising and movies [Untitled Film Stills began in 1977]. And now here’s Shore, right there in the thick of things, making giant photos with his new-fangled, trade show backdrop printing techniques–which turn out in the end to actually be paintings. [And sculpture. And architecture.]

The kicker, though, is one of the complicating factors for why I’m finding photomurals so interesting right now. And I write this as a guy who has two of Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ Parkett billboard/photomurals because, once you install one, it’s up, it’s done, it’s gone: they managed to thwart the market. Here’s Lugon:

The photomural reveals itself to be extremely vulnerable. Its own installation, its dependence on conditions of fixation and lamination make it enormously fragil: with rare exceptions, it does not survive its exposition. It’s one of the fundamental points that distinguishes it from painting: its incapacity to become an object of collection.

When it was developed in the 19th century, photography constituted precisely a pure image for collecting: one acquired it to conserve, because it was capable of bringing all objects in the world together into a system of thesaurisation and generalized comparison, but it’s difficult to show. Small and grey, taking poorly to the wall, and with a surface that deteriorates in the light the more one views it. The grand format photos of the interwar years reversed this logic: photography became the image of exposition, but it renders it improper for collecting.

Only the forme tableau would succeed in crossing these two qualities, to make of photography an image at once for exhibiting and collecting–two criteria indispensable for accessing fine art’s economic system.

I guess I’ve gotta call Stephen Shore now and see if that’s really true, about his photomurals, I mean.

What I Didn’t See

The other weekend, I pigeonholed former Washington Post art critic Paul Richard after his talk, titled “What I Saw,” at the National Gallery of Art. I said that I’d been interested to hear his take on public art over his 40-year career, and he answered back, “What public art?” “I guess that was my real question,” I said.

Richard then made a quick and familiar explanation that public art is outdoor art, outdoor art is sculpture, museums in town focus on painting, and so sculpture generally and outdoor sculpture specifically is marginal[ized].

I had this exchange in my mind when I watched the Post’s current art critic Blake Gopnik effuse over his “favorite new discovery,” a massive Alexander Calder sculpture that has been sitting on one of downtown Washington’s busiest intersections for almost 30 years.

Gopnik said that in a series of Post web videos called, “The Wonders Around Us.” He opens another, featuring the chair-shaped granite sculptures of the late Scott Burton, thus: “I’m at the Sculpture Garden of the National Gallery, looking at works I don’t often look at–the ones they keep outside.”

In another video, discussing Richard Lippold’s 100-foot-tall steel starburst sculpture Ad Astra, in front of the National Air and Space Museum, he ends on what he imagines is a poignant and/or ironic note:

Amazing how you look at this thing, and you realize that almost no one but you is looking at it. Not a single head turned up to look at poor Richard Lippold’s magnum opus.

[Let’s ignore the fact that if Lippold has a magnum opus, it’s probably Orpheus and Apollo, which glitters across the atrium lobby of Avery Fisher Hall. Gopnik was going for pathos, and couldn’t very well call Ad Astra a “masterpiece” so soon after calling it a TV antenna.]

Days later, Gopnik was writing about Hirshhorn director Richard Koshalek’s proposal to renovate the museum’s sculpture garden on the Mall and add indoor exhibition space to/under it, since the current sculpture setup is “dormant,” rather than “lively,” and [anecdotally, at least] is always empty.

Which may be true, but that’s not [quite] the point. And [for once or twice] I don’t want to pick on Gopnik; in this case, I think his forthright ignoring of outdoor sculpture is probably in sync with the general population of DC. The city is stratified and carved up into ghettos for tourists and locals alike. Commuters, whether in cars or trains, on bike or on foot, rarely venture off their routes.

Outdoors, art, or sculpture in a drive-by situation quickly becomes invisible, receding into the landscape passing outside the window. But is that actually just a DC thing? I don’t think so. Is it even just a city thing? Is it even just an art thing? How quickly does something become invisible, and why? What happens to art in such a context? Has someone written about this with intelligence or insight?

Is it even just outside? We like to think that art rewards close or considered looking. But how long do most people look at most artworks in most museums? [answer: for less time than it takes to read the label next to it.] Do professional art lookers sit through every blackbox video installation they enter, or do they only watch long enough to “get it”?

When I started, I thought I was writing this about DC, its critics, its particular context, sculpture, outdoor art. See how the circle keeps expanding to include everything? Now I’m a little bummed out.