I didn’t realize how closely the Modern’s 1932 Murals and Photomurals exhibition and the anti-communist controversy it provoked dovetailed with the far better known confrontation over Diego Rivera’s rejected and destroyed commission at Rockefeller Center.

Rivera had a hugely successful one-man show at MoMA in 1931. Lincoln Kirstein’s exhibition of murals by American artists was, as he said in the catalogue, “Stimulated in part by Mexican achievement, in part by recent controversy, and current opportunity.” The recent controversy, it turns out, was a January 1932 protest by art students from the New School, who objected to reports that John D. Rockefeller Jr. had selected foreign artists, Rivera and Jose Maria Sert, not Americans, to paint murals in Rockefeller Center. Check out this incredible NYT headline:

WANT NATIVE ART IN ROCKEFELLER CITY; Students Protest on Hearing A Report That Rivera and Sert Are to Paint Murals. ARTISTS NOT YET CHOSEN Architect Promises Citizens Will Have an Equal if Not Better Chance for Commissions. FOREIGNERS CRITICIZED Class at School for Social Research Declares Selection of Any Aliens for Building Here “Inconsistent.”

Which means the Modern’s show, which came together in a matter of weeks, was more an attempt by the Rockefellers to blunt nativist criticism in the wake of a Rivera lovefest as it was a helpful promotion of the work of American artists for anyone who might find himself in the market for a few thousand square feet of murals. [And for the record, ascribing this decision to the Rockefellers and not the Museum per se is fine; the show originated in the Advisory Committee, headed by the 23-yo Nelson Rockefeller.]

But this also means that trustees’ objections to anti-capitalist-themed works, and the ensuing threats of a protest and boycott by a dozens of artists in the show, did not happen out of the blue; they occurred in the context of the Depression, where anti-foreign sentiment was as readily expressed as anti-capitalism. And more to the point, it happened in and around a Museum founded by the family that was the symbol of capitalism, who was in the middle of one of the largest building projects in history.

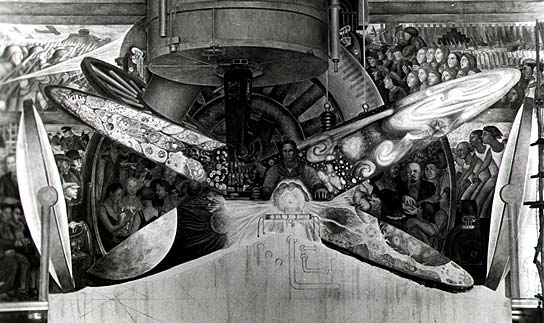

And sure enough, that fall, Rivera was announced as John D. Rockefeller’s pick for a fresco in the complex’s flagship, the RCA Building. It can’t have been a naive decision. The day after Rivera arrived to begin work on the Rockefeller Center mural, his just-finished mural cycle at the Detroit Institute of the Arts, Detroit Industry, came under attack for “blasphemy.” [The DIA had invited local religious leaders to comment on it, and because one small panel in the upper corner depicted a swaddled baby being vaccinated by three wise scientist men, some clerics demanded the work be destroyed. Go figure.]

The Times kicked off its play-by-play coverage of the project by “the fiery crusader with a paint brush,” by noting “DIEGO RIVERA is again the centre of a raging controversy. and his new job at the RCA Building in the Rockefeller Center is likely to provoke another.”

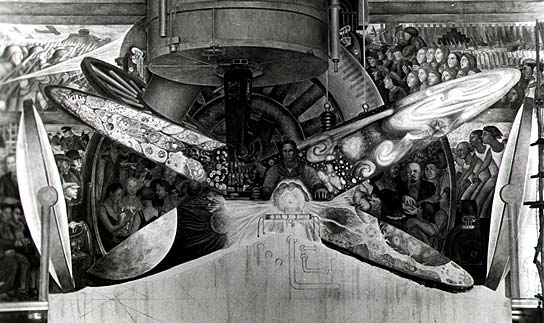

And sure enough, less than three weeks later, after it became clear that that was no random baldheaded, goateed man in the center of Man At The Crossroads with Hope and High Vision to the Choosing of a New and Better Future, but Lenin himself, Nelson Rockefeller was called in to persuade Rivera to genericize the figure. Rivera refused, and he was quickly paid off and barred from the premises. Eager to not have the nearly-completed work photographed, the Rockefellers first covered it with drapery, and within a day, had covered it with canvas. After unsuccessful attempts spearheaded by Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, John D’s wife, to salvage the mural, perhaps to put it in the Modern, it was destroyed. Which prompted workers to protest anew in April 1934.

Now I knew it was a controversy, but I had no idea how heated and seat-of-the-pants the whole situation was, nor what a spectacle. It was on the front page of the Times for days, weeks, even. I also didn’t realize how incredible it was that Lucienne Bloch managed to take the only photos of the mural before it was covered up. Bloch began working as Rivera’s assistant after she was seated next to him at the Modern’s 1931 opening dinner.

The whole photo drama was retold [with perhaps a bit of anti-capitalist gloating?] in Bloch’s obituary in 1999:

Lucienne Bloch, an acclaimed muralist whose most significant contribution to art may have been a series of surreptitious photographs she took in 1933, died on March 13 at her home in Gualala, Calif. She was 90.

She was the photographer whose sneak pictures taken behind enemy lines on May, 8, 1933, are the sole visual record of the great Diego Rivera’s ill-fated Rockefeller Center fresco with its doomed depiction of Lenin.

At a time of economic distress, when capitalism itself seemed vulnerable to competing currents of social change, if anybody was going to pin Lenin on a capitalist wall it was Diego Rivera, the fiery Mexican muralist whose artistic acclaim was matched only by his reputation as a fiercely committed, if renegade, Communist.

If anybody was going to stop him it was John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s son, Nelson A. Rockefeller, who had commissioned Rivera to paint a 1,000-square-foot fresco, ”Man at the Crossroads,” in the great hall of the new RCA Building, the soaring Rockefeller Center capstone now known as the G.E. Building and at the time an especially potent symbol of capitalism.

Rivera used Bloch’s photos to recreate the Man at the Crossroads later in Mexico City.