In anticipation of Creative Time Summit II–it’s October 9-10, just a few weeks away!–I’ve been watching some of the talks from last fall’s Summit, organized by Nato Thompson held at the NY Public Library. [For an overview, check out Frieze’s write-up of the quick-fire speechifying marathon.] Like the Oscars, speeches are cut off right on time by pleasant music. It can be kind of harsh [sorry, Thomas Hirschhorn and guy from Chicago’s Temporary Services making his big, final pitch for help] but rules are rules.

So far, I’ve found the longer [20m vs 7m] keynote speeches to be the most fascinating. From the super-low viewer numbers to date, the fan club is pretty small. Anyway, watch these and pass them around:

Teddy Cruz, the Tijuana/San Diego architectural investigation guy has the single most intense 6:30 min talk I think I’ve ever seen. Almost makes up for not being able to see his slides.

Art historian Morris Dickstein’s keynote about Evans, Steinbeck, Astaire, and art of the Depression was interesting and timely, easily the most wrongly underappreciated, too:

Okwui Enwezor’s talk was smart and incisive, unsurprisingly, and made me wish he’d talked longer–and about more than a single documentary photo used by Alfredo Jaar.

But by far the best, the most moving, the one that got my head nodding and made me want to write things down for later, was Sharon Hayes’ reminiscence of moving to New York in 1991, smack into the middle of a teeming downtown art/activist community dealing with the AIDS crisis. It was gripping, and made me remember how important, vital, art can be, not for the the objects it generates, but for the effect it has on people, singularly and together, at a moment and in a place.

Creative Time New York YouTube Channel [youtube]

Category: architecture

Westinghouse World’s Fair Pavilion, Or Eliot Noyes’s Huge Shiny Balls

I love Eliot Noyes as much for his own designs as for his role as catalyst, instigator and patron for some of the greatest modernist objects and buildings of the postwar era.

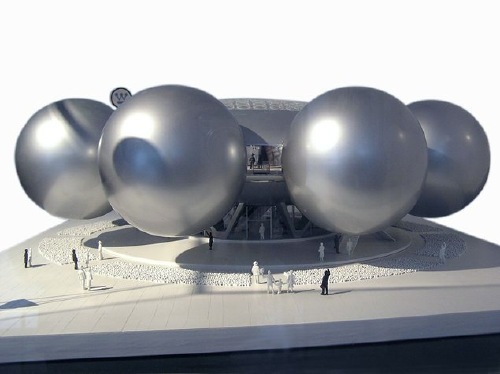

And yet somehow I hadn’t made the connection to his unrealized design for the Westinghouse Pavilion at the 1964 New York World’s Fair, which consisted of eight 45-foot diameter silver spheres floating off of a central domed foyer. Giant silver spheres in 1961? Wherever would the idea for such a form come from?

Thanks to dealer-turned-design curator Henry Urbach, SFMOMA acquired the Westinghouse maquette in 2006, but the museum’s description doesn’t make any reference to Project Echo or any design references at all.

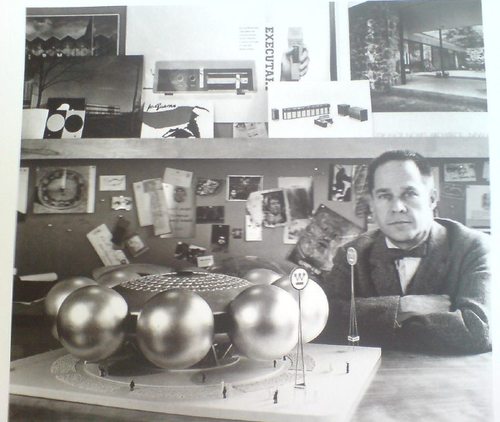

Next, I turned to Phaidon’s sleek-yet-frustrating Eliot Noyes monograph, written by Noyes’s longtime collaborator Gordon Bruce. Though it’s chock-full of info and photos [including the one above, of Noyes posing with his maquette], it turns out to be more bio snapshot than design history. There’s a little about the bureaucratic wrangling that nixed the pavilion [and replaced it with a second company time capsule, to match the 1939 one], but nothing about the design.

Oddly, there’s no mention at all of the scaled-down pavilion which was eventually built [image via], even though it has the maquette’s signage, and it looks awfully similar to the round gas station canopies Noyes would design for Mobil a couple of years later. [image via agilitynut.com’s great collection of gas station design photos]

update: indeed, Noyes & Assoc. are credited in the World’s Fair Time Capsule Pavilion Brochure, which turns out to be the uncredited source for Wikipedia’s image. That’s the torpedo-shaped time capsule right there, btw, suspended 50-ft above the ground by the three masts.

Eliot Noyes, Westinghouse Pavilion, 1961 [sfmoma.org]

Oh No, There’s A Deutschen Bundespost Type TelH78 Telephone Booth On eBay

I’ve been trying for months to figure out the designer of what I think is one of the slickest phone booths around, the Deutschen Bundespost Typ TelH78 Telefonzelle.

I’ve been trying for months to figure out the designer of what I think is one of the slickest phone booths around, the Deutschen Bundespost Typ TelH78 Telefonzelle.

You know it when you see it. It’s bright yellow, a fiberglass and safety glass box with beautiful rounded corners. It has just the stability, utilitarianism, officialism, and future-forward design you’d expect from a European, state-run telecommunications monopoly in 1980, which is when I think they started deploying them. [Near as I can tell, the type number refers to the year it was designed.] It’s the Helvetica of phone booths.

And it’s disappearing, if not completely gone. I haven’t roamed the German byways to see how far T-Mobile’s awful magenta & glass booths have taken over, but these days, phone booths themselves seem barely more than excuses for street advertisements. A few Telefonzellen, including TelH78s–oh, wow, look at that olive drab one–are being converted into tiny, neighborhood lending libraries.

And now one’s on eBay.de. In beautiful condition, a mere EUR71. For local pickup in Fritzlar, just outside of Kassel. Weighs around 100kg. So beautiful, so tempting.

Telefonzelle der Deutschen Bundespost, ends Aug. 19 [ebay.de]

Telefonzelle (Deutschland) [wikipedia]

The Raum der Gegenwart, Then And Now

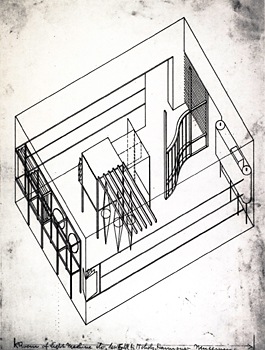

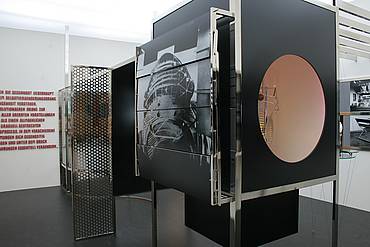

In addition to being the subject of his film and photographic work, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s Light Space Modulator modulated light and space as a sculptural installation, and it served as a Light Prop for an Electric Stage. But in 1930, the artist had also planned on installing it at the Hannover Provincial Museum.

In addition to being the subject of his film and photographic work, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s Light Space Modulator modulated light and space as a sculptural installation, and it served as a Light Prop for an Electric Stage. But in 1930, the artist had also planned on installing it at the Hannover Provincial Museum.

Alexander Dorner, the director of the Landesmuseum, had invited Moholy-Nagy to design the final room in the chronological reinstallation of the museum’s collection, the Raum der Gegenwart, The Room of the Present Day. The room was to have interactive exhibition elements devoted to film, architecture, and design. And at its center: the definitive art work of Moholy-Nagy’s future, the Light Space Modulator, performing inside its light-lined cabinet. Was to have, because Moholy Nagy’s plans were never realized in Hannover.

Frankly, it sounds more like the Room of the Multimedia Future. In the press release for Licht Kunst Spiele, an exhibition of Light and the Bauhaus last year at the Kunsthalle Erfurt, the Room of the Present Day was said to have anticipated “an art which does completely without the hand-painted, auratic picture.” [Anticipated is right; Walter Benjamin didn’t write “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” until 1935. I guess aura was in the air.]

And speaking of reproduction, the curators for that show, Drs. Kai Uwe Hemken and Ulrike Gärtner teamed up with designer Jakob Gebert to finally realize Raum der Gegenwart according to Moholy-Nagy’s designs and intentions. From the photos, the Raum looks like a life-size Light Space Modulator, the Light Prop transfigured into a Light Stage. Or Light Theatre.

The Raum traveled to Frankfurt for the Schirn Kunsthalle’s Moholy-Nagy retrospective, and it has now settled into the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, where it is part of Museum Modules, a show about, I guess, famous museum exhibition re-enactments. [images via crossroads mag and vanabbemuseum.nl]

Whether that is the Van Abbemuseum’s 1970 Light Space Modulator in there, or yet another replica, I don’t know, but I’ll assume it’s the former. Perhaps the answer lies in “The Raum der Gegenwart (Re)constructed,” a thorough and fascinating-sounding article by Columbia’s Noam M. Elcott, which was recently published in the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians.

update: Yes and no. Elcott’s article is fascinating, though, and he praises the “historical acumen and curatorial courage” of putting the Light Prop in the lighted box it was arguably conceived for. He goes further, arguing persuasively that Light Prop, as an embodiment and producer of cinematic abstraction, is the conceptual center of the Raum der Gegenwart. Very interesting stuff.

Two Degrees Of Project Echo: Les Levine’s Slipcover

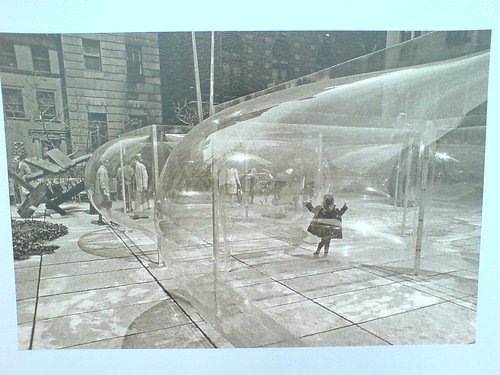

Holy smokes, people, just watch how these things turn out. In April, I spotted this photo at MoMA; it was in the second floor hallway just past the cafe, with no caption, and a date: 1970. I spent a few weeks trying to search up the name of the artist who made this remarkable, undulating acrylic structure in the Garden, to no avail [MoMA’s records didn’t have any more info about the photo.] I looked through the archive of shows, trying to match it, nothing.

Look at that thing, though, it’s like an ur-Dan Graham. an ur-Greg Lynn, for that matter. A more permanent Ant Farm inflatable. Suddenly, it occurred to me to ask John Perrault, who’s probably forgotten more than I’ll ever know about postwar art in New York. Sure enough, he nailed it: Les Levine. Star Garden, but 1967, not 1970.

Turns out 1967 was a great year for Levine–actually, looking through his works at the Center for Contemporary Canadian Art, a lot of years were great years for Levine. The Silver Environment (1961), vacuum-formed mirrored plastic? fabric? The perceptually disorienting acrylic bubble structures like Star Garden or Supercube Environment (1968)?

Disposables (1968) [above], a pop-minimalist grid of vacuum-molds of household objects, sold cheap and meant to be thrown away when their moment is over? Wow, Levine’s Restaurant (1968), New York’s only Canadian Restaurant, operated as a artist project, like Gordon Matta-Clark’s Food or Allan Ruppersburg’s Al’s Cafe, only earlier? Is that really TV test pattern print clothing there in 1978?

And then there’s Slipcover, a 1967 installation at the Architectural League [image via], which ran concurrently with Star Garden: three rooms covered in sheets of mirrored Mylar, where the space is constantly in flux because of the giant Mylar balloons inflating and deflating. The NY Times article shows Levine working on a balloon while one Linda Schjeldahl seals the edges of the Mylar wallcovering. Schjeldahl, Schjeldahl, where have I heard that name before?

Of course! The University of North Dakota’s archives of Gilmore Schjeldahl, founder of the Sheldahl Company!

The Company was the primary contractor for the Echo II Program. There are also files which contain information about the Echo I and II satellite balloons, as well as samples of Echo I and Echo II skins, and a file containing information about an art exhibition by artist Les Levine in 1967, at the Architectural League in New York City, which featured rooms made of Sheldahl’s Mylar laminates.

Billy Kluver, whose company Bell Labs operated the Project Echo satelloons, introduced Andy Warhol to Mylar and helped him make his 1966 Silver Clouds.

Meanwhile, the manufacturer of those satelloons supplied the same Mylar for Les Levine’s 1967 Slipcovers. Who had some help installing from his friend Linda Schjeldahl, the daughter-in-law of the company’s founder. A friend who, like her husband, Peter, was somewhat involved in the New York art world at that point.

All The Named Buildings On The Ocean Road Strip

View Larger Map

Like leisure boats, beach houses in Emerald Isle, NC, where our family has gone for many years, are often given names. It appears that the practice tracks somewhat the expansion of the beach cottage rental directory business.

It may be nostalgia-induced prejudice and my disdain for the neon Floridization of Outer Banks cottage architecture, but it seems to me that older cottages’ names aim for a kind of naturalistic postcard sublime, while the newer, larger, flashier McVillas have punnier, more self-congratulatory, more yacht-like names.

Anyway, on a recent trip, I decided to catalogue the house names along a stretch of Ocean Road, heading eastward, and ending with the best name of all, which is on the house above:

Top Notch

Windy

Sunspot

Impossible Dream

Granted Wish

Skinny Dipper

Continue reading “All The Named Buildings On The Ocean Road Strip”

Len Lye’s Wind Wands Saved The West Village

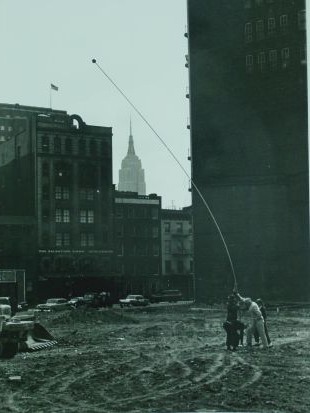

Len Lye called his kinetic artworks Tangible Motion Sculptures, or just Tangibles, because they made visible motion and other phenomena, like the wind. In 1960, he and his wife Ann, along with some other friends, headed over to huge vacant lot near their home in the “West Greenwich Village,” and set up the first Wind Wand. It was a 40-foot aluminum tube with a small sphere on the end to catch the breeze.

Judging by this photo, from the Len Lye Foundation at New Zealand’s Govett Brewster Gallery, where the wand is leaning in the opposite direction from the blowing flag, this Wind Wand was a little too long and heavy to work quite right.

Also, the photo is backwards. That vacant lot, at the corner of Horatio and Hudson Streets, is now a city park. The building houses White Columns. Here is a correct version, followed by the current site on Google Street View.

Which reminds me, I hope the preservationists are taking up the cause of cobra head street lights.

By 1961, Robert Moses had announced plans to raze the West Village, including the Lyes’ house in Bethune St and their neighbor Jane Jacobs’ place and replace it with high-rise residential towers. To prove that their neighborhood wasn’t a slum, local artists rallied to stage a one-day exhibit at St Luke’s Chapel. Though Franz Kline apparently contributed a painting inside, the Times’ small article didn’t mention him, only the presence of Lye’s eight Wands in the playground. Roger Horrock’s biography of Lye quotes an unnamed news source as saying the St Luke’s wands, which ranged “to nearly 30 feet,” were a hit with the kids: “The wands became ultra-modern May Poles just right for a junior bacchanal.”

Lye later installed two Wind Wands on top of their house on Bethune Street, and five at NYU, where he taught. Miraculously, their gentle, hypnotic swaying fended off the forces of flashy, high-rise redevelopment, thereby preserving the West Village forever as a quirky, affordable haven for artists of all sorts. And so it remains to this very day.

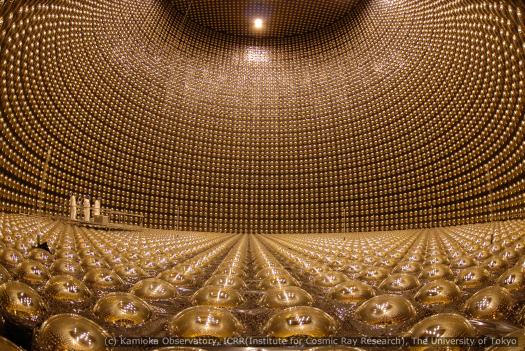

The Hamamatsu Photonics R1449 And R3600 Photomultiplier Tubes

Photomultiplier Tubes, or PMT, are vacuum tubes used to detect electromagnetic energy. In 1979, Hamamatsu Photonics began development of the world’s largest PMT, 25 inches across, which would be used in the Kamiokande proton decay detector being constructed by the University of Tokyo in a mine in rural Japan.

Photomultiplier Tubes, or PMT, are vacuum tubes used to detect electromagnetic energy. In 1979, Hamamatsu Photonics began development of the world’s largest PMT, 25 inches across, which would be used in the Kamiokande proton decay detector being constructed by the University of Tokyo in a mine in rural Japan.

Within a year, Hamamatsu had managed to design a 20-inch (50cm) PMT, and successfully manufactured it by 1981. It was dubbed the model R1449:

Because this was a 20-inch PMT, the biggest question was whether or not its cathode could be manufactured correctly. The days leading up to the completion of the first PMT were anxious. Moreover, in steps such as antimony evaporation, there was no other recourse but to rely on the eyes and judgment of those professionals performing the tube evacuation task. An ordinary PMT can be held in the worker’s hand throughout the production process, but the large 20-inch PMT first had to be secured in place. Then, the worker could perform his required tasks while walking around the outside of the PMT. The workers donned protective helmets equipped with explosion masks, mounted steps to the platform holding a large pumping bench, and began the final fabrication, which consisted of making the photocathode and sealing the PMT.

The color formed from oxygen discharge in the photocathode manufacturing process was visually attractive. When made to react with potassium after antimony evaporation, the tint immediately changed to an ideal color for a photocathode. Cheers arose from the staff gathered around the pumping bench, as it was a moment of high emotion for everyone.

Hamamatsu delivered 1,050 R1449 PMTs to Kamiokande, where they lined a giant tank of ultra-purified water 1,000 meters below the surface.

In 1987, the PMT array at Kamiokande detected for the first time neutrinos given off by a supernova. [It was a discovery for which Professor Masatoshi Koshiba [above], who spearheaded the Kamiokande research, was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2002. Those may be the two most awkwardly constructed sentences in this post.]

Meanwhile, an even larger detector was being planned for Kamiokande. Dubbed Super-K, the new tank, 39m high and 41m in diameter, would hold 50,000 tons of water and 11,200 PMTs. These new, improved PMTs, known as model R3600, were based on the R1449. They cover approximately 40% of the interior surface of the tank. Super-K began operations in 1996.

On November 12, 2001, as the tank was being refilled, a PMT imploded, sending a shock wave through the water, and causing a chain reaction which destroyed around 6,600 other PMTs.

The survivors were redistributed, protective acrylic shells were added, and research resumed. Beginning in 2005, newly manufactured R3600s were installed. The detector reopened in 2006 as Super-K-III.

According to reports at the time of the implosion, an R3600 cost around $3,000 new, an extremely reasonable price for such a magnificently crafted object. I would most definitely like one. Also a convenient display stand. Also, that tank is absolutely stunning. If I were a sculptor of shiny round objects of a hundred feet or more in diameter, I would find it hard to get out of bed in the morning knowing this exists.

20-Inch Photomultiplier Development Story [hamamatsu.com, the original Japanese version is a little more dramatic]

portrait of Prof. Koshiba hugging a Hamamatsu R3600 [u-tokyo.ac.jp]

hi-res images in the Super-Kamiokande photo album [ICCR at U-Tokyo]

Accident grounds neutrino lab [physicsworld]

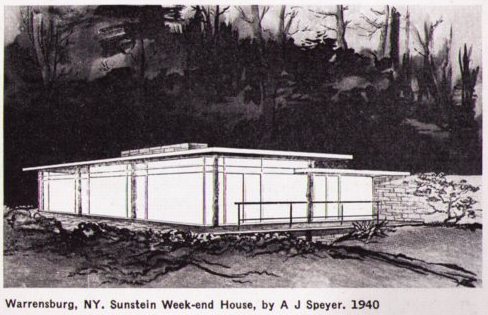

Your Search For A. James Speyer’s Sunstein House Now Returns Three Google Results

In 2008, I discovered this drawing of A. James Speyer’s Sunstein House, a 1940 modernist pavilion in the Adirondacks made of tree trunks and local stone, in an architecture guidebook published by The Museum of Modern Art. Even though the guidebook gave driving instructions, the lack of photographs, combined with utter online silence about the project or the client, made me wonder if the house actually ever got built at all.

Now, while searching for images of the house Gregory Ain built in MoMA’s garden in 1950, I found that the Museum has since published its archive of press releases. And it seems that Speyer’s Sunstein House was at least real enough to be included in a traveling exhibition the Museum organized in 1941 titled, “The Wooden House in America.” [pdf] So the search is back on.

Speyer is probably best known for his work as a modern curator at the Art Institute of Chicago; Anne d’Harnoncourt cited his influence regularly and his innovations in both curation and exhibition design. But he also practiced architecture, primarily in Chicago and his hometown of Pittsburgh. His 1963 house for his mother Tillie Sunstein Speyer is his most widely praised work, but his most famous work is the Ben Rose house, from 1953, which he designed with David Haid. It was Cameron’s house in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. [Which is still for sale, btw, asking $1.65m, down from last year’s $2.3m.]

Anyway, Speyer got all International Style like that because he was Mies van der Rohe’s first graduate student in the US, and the Sunstein House dates from the time he was studying directly with Mies. And it’d predate by a decade Mies’ own first realized American buildings. So we’ll keep on it, and see what’s out there.

Previously: Forest for the Mies: A. James Speyer’s Adirondack Mystery Cabin

Wilkommen To The German Dome

Found The Kocher Studies Building!

Looks like I picked the wrong end of North Carolina. While I was bumming around the Outer Banks, Mondo Blogo was surely doing The Lord’s Work in the mountains. Black Mountain College, to be precise, or what’s left of it.

He and his mom [!] visited Camp Rockmont, the Christian boys camp on the shores of Lake Eden, which absorbed BMC’s homebrewed modernist buildings after the school closed. There are great photos of A. Lawrence Kocher’s 1940-1 Studies Building, a low-slung, low-key, low-budget International Style marvel of corrugated metal siding and ribbon windows. Including this one, which features the old re-bar cross or somesuch.

If you can piece it together from the BMCProject website, the architectural story of Black Mountain College is as fascinating as the art and curriculum. Kocher, the editor of Architectural Record, was the last-minute replacement for Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer. He was also the collaborator on Albert Frey’s first building in the US, the 1931 Aluminaire House, which bears a strong family resemblance to the Services Building.

After discovering that building and pulling it online last summer, I stumbled across a Black Mountain College mystery, a cool, little, unidentified plywood building that I speculated might have been by Kocher. It turned out to be Paul Williams’ Science Building, built in 1949-50 with the help of students Dan Rice and Stan VanDerBeek.

Is there a beautiful, comprehensive exhibition and catalogue for Black Mountain College? Because I really think there oughta be.

Black Mountain Madness [mondo-blogo]

More Is More: Warhol’s Silver Clouds In Mies’ Crown Hall

Bell Labs’ Billy Kluver guided Andy Warhol to the Mylar balloons the artist used for Silver Clouds, his 1966 installation at Leo Castelli Gallery. And at Ferus Gallery. And at the Cincinnati Arts Center.

At the time, Bell Labs was operating both Project Echo satelloons; after Echo II’s launch in 1964 until Echo I’s disintegration on re-entry into the atmosphere in 1968, these two giant Mylar balloons were visible with the naked eye around the world.

Flash forward to this week, when the Mies van der Rohe Society opened the largest Silver Clouds installation ever, somewhere between “hundreds” of balloons and “1,000” at the Illinois Institute of Technology’s Crown Hall.

At current Armory Show prices, that’s up to $5 million worth of balloons!

ANDY WARHOL’S SILVER CLOUDS FILL S. R. CROWN HALL, through Aug. 1, 2010 [iit.edu via c-monster]

video: Warhol and Mies: Floating Silver Clouds [edwardlifson]

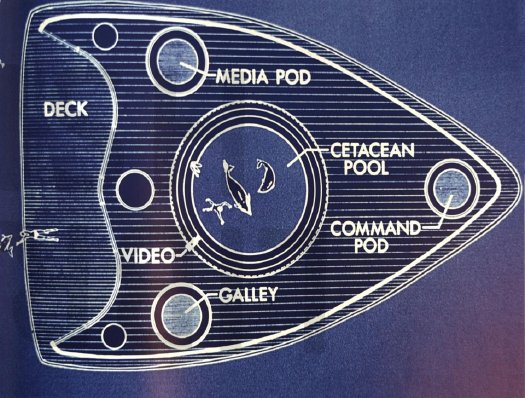

Cue The Dolphin Embassy

The architecture and art collective Ant Farm first proposed The Dolphin Embassy in Esquire magazine in 1974. When they ended up meeting the owner of the Dolphinarium in Australia a couple of years later, they worked it up into a full-fledged proposal, which got funding from the Rockefeller Foundation and a show at SFMOMA.

Basically, the idea morphed from an underwater building into an open, mobile laboratory craft [above] to facilitate human-dolphin interaction in the wild. [spatial agency has images of both early designs.] First, they would deploy the awesome power of video technology to create a common language with the dolphins. Then…

Here’s Ant Farmer Doug Michels talking about the project with Connie Lewallen in the catalogue for the 2004 retrospective at Berkeley Art Museum:

The next year and a half for me [from 1977-8] was filled with trying to make the Dolphin Embassy real. There was a lot of time spent with both captive and wild dolphins and researching dolphins, a lot of design time on the boat, and a lot of public relations time communicating the dolphin idea to Australia. Putting it in historical context, we were feeling pretty confident about accomplishing things. The House of the Century had been built, Media Burn had been done, The Eternal Frame–these large-scale productions. Cracking the dolphin communication code, well, how hard could that be?! (Laughs.)

CONNIE: Why didn’t the Dolphin Embassy get built?

DOUG: Eventually, it became clear that it was a gigantic project beyond the scale we could accomplish with the funds we had raised. While we didn’t solve cetacean communication during our mission in Australia, the Dolphin Embassy experience provided a deeper view into the mysteries of Delphic civilization.

A few months ago Andrea Grover posted this great 1976 photo of a TV-toting Michels having a diplomatic summit of some kind with his dolphin counterpart. Not sure what they discussed.

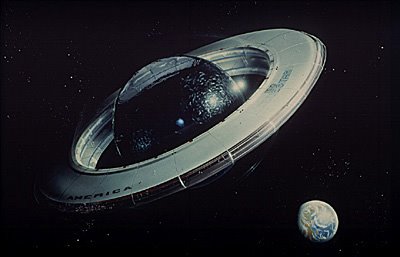

From the disbanding of Ant Farm in 1977 up until his unexpected death in 2003, Michels kept developing the Dolphin Embassy concept. By 1987, it was retitled Bluestar, a joint dolphin-human-compatible space colony with a 250-ft diameter sphere of water “ultrasonically stabilized” within a wall of space-made glass. My merely 100-ft satelloon bows in awe at the thought.

Anyway, I’m reminded of all this now because, with the iPad and all, it may be time to dust off those Dolphin Embassy blueprints.

Speak Dolphin press release at Orange Crate Art [mleddy via boingboing]

Doug Michels, Dolphin Lover [andreagrover.com]

Orbit: Final Conflict

Took me a couple of months, but I finally figured out which, out-of-place alien Washington embassy in the short-lived, suspiciously-generous-aliens-move-into-Earth TV series Anish Kapoor’s wacked out Orbit Tower reminded me of: the one in Gene Roddenberry’s Earth: Final Conflict.

Glad to have that off my plate.

Into Orbit [kosmograd via things]

[images via willwiles and rivenwolf]

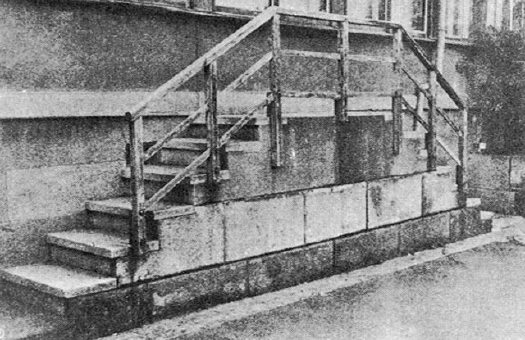

Tomasons And Akasegawa Genpei, Translated

I’ve got browser tabs full of sweet, sweet updates and extensions to some earlier posts. I’ll start with Tomasons.

Tomasons [also Thomassons], but really, トマソン, are the inadvertent, useless architectural leftovers, vestiges of a city’s churned and rebuilt history. They were invented/ discovered and documented beginning in the 1980s by the Japanese art/architecture collective Rojo Kansatsu [Roadside Observations] and its co-founder Akasegawa Genpei.

At the time, Japan was in the middle of a crazy, real estate-fueled economic bubble, and the built environment was in constant flux. Akasegawa made Tomasons the humorous, overlooked fodder for a magazine column, the compilation of which became a hit in the 80s.

Now, thanks to Kaya Press, Akasegawa’s Thomasson writings have been published in English. Should be great stuff. [via metafilter]

Previously, 02/08: On Tomason, or the flipside of Dame Architecture

Related: Roadside Observation [neojaponisme.com]

Related from last week: Berthier’s (and Boudvin’s) Door, a fake Tomason in Paris [bldgblog, who else]