I’ve got browser tabs full of sweet, sweet updates and extensions to some earlier posts. I’ll start with Tomasons.

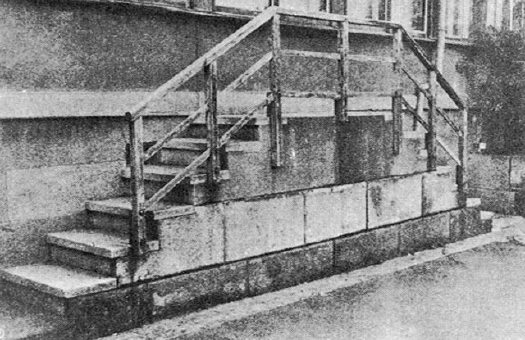

Tomasons [also Thomassons], but really, トマソン, are the inadvertent, useless architectural leftovers, vestiges of a city’s churned and rebuilt history. They were invented/ discovered and documented beginning in the 1980s by the Japanese art/architecture collective Rojo Kansatsu [Roadside Observations] and its co-founder Akasegawa Genpei.

At the time, Japan was in the middle of a crazy, real estate-fueled economic bubble, and the built environment was in constant flux. Akasegawa made Tomasons the humorous, overlooked fodder for a magazine column, the compilation of which became a hit in the 80s.

Now, thanks to Kaya Press, Akasegawa’s Thomasson writings have been published in English. Should be great stuff. [via metafilter]

Previously, 02/08: On Tomason, or the flipside of Dame Architecture

Related: Roadside Observation [neojaponisme.com]

Related from last week: Berthier’s (and Boudvin’s) Door, a fake Tomason in Paris [bldgblog, who else]

Category: architecture

National Houses, Inc.

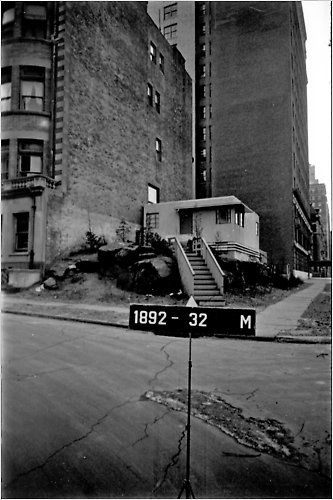

So weird/awesome. A steel panel, prefab, moderne house designed by William Van Alen, and built on top of a craggy boulder at 107th & Riverside, in 1937, seven years after completing his somewhat higher profile project in Midtown, the Chrysler Building?

Christopher Gray has the story–and finds this picture in the Municipal Archives–in

NYT’s Streetscapes column.

According to “A Home in Cellophane,” a chirpy 1935 Time story about prefabs [found via the Van Alen Institute], Van Alen was actually a director of National Houses, Inc., just one of several prefab startups that were going to pull America’s housing market out of the Depression.

The focus of Time’s article was actually another venture, American Houses, Inc., who unveiled architect Robert McLaughlin’s modular, modernist “machine in which to live,” the Motohome, at Grand Central Palace, the same place where Albert Frey & Lawrence Kocher’s Aluminaire House had debuted in 1931. [Aluminaire was extensively re/dis/covered here on greg.org in August 2009. Here’s a contemporary photo by curator Erik Neil of the house, which is currently on the Islip campus of the NY Institute of Technology.]

Aluminaire was a hastily constructed one-off; the Motohome was a product. It went on “sale,” tied with a red bow, and wrapped in cellophane [like the future!] at Wanamaker’s department store on April 1. [The half of Wanamaker’s that didn’t burn to the ground now houses the Astor Place KMart.] There must be some publicity shots or newsreels of this somewhere.

As our country is not dotted with tens of thousands of early International Style or Moderne steel- or asbestos cement-paneled cottages being tended and detoxified by new generations of design-loving caretaker owners, these products failed.

American Houses scrambled to traditionalize its design and materials, and apparently sold around 150 peaked-roof, woodframe Motohomes by 1938. But as of 1991, it sounds like only two of McLaughlin’s original modernist Motohouses were still standing; that was when one was discovered in New London, CT, and preservationists persuaded its owner, Connecticut College [image via] to restore, not demolish it. Now the College is working to restore the other modernist prefab next door, dubbed The House of Steel. [Both were bought and used as rental properties by an adventurous museum director named Winslow Ames, who wanted to test the 1930s media’s prefab hype.]

Van Alen’s National Houses designs did not fare so well. In 1936, his 2-story steel prefab design, called “The House of the Modern Age,” was erected for three months on a vacant lot at 39th & Park. It’s the little white box in Berenice Abbott’s photograph:

The house at 107th & Riverside was an exhibition house, too. And it was obviously torn down, because if it still existed, I’d be living in it. I can’t find any other mentions of Van Alen’s prefab structures being built, much less surviving.

[2022 UPDATE] Did I hallucinate or didn’t at least one of Van Alen’s houses get transported to Westchester somewhere, and I saw it for sale a couple of years ago buried under an epic amount of upscale renovations?

What I do know is that Dan Nichols emailed to say he came across a Van Alen house in Miami. Apparently in 1936, Clarence Beecher, the Florida rep for National Houses, Inc., built himself a company house in Shorecrest, off Biscayne Blvd. It has been subsumed by the local vernacular: stucco and tile roof, but in its heart beats the metal paneled prefab House of The Future.

Please Go To Philoctetes Tonight And Tell Me How It Was

My buddy John Powers has been working on this insane project forlikeever: an artists commentary track–with pictures!–that runs alongside Star Wars IV. Tonight he’s presenting it at Philoctetes, and discussing it along with Colby Chamberlain and Luke duBois, who’s made a sick score.

I’ve seen pieces Star Wars and Modernism: an artists commentary emerge in pieces over the months, but tonight’s the first time a big section of it will be screened large, and in public. I’m very jealous of all those who can make it out there tonight:

Star Wars and Modernism, an artist commentary conceived and directed by artist John Powers, explores the original 1977 science fiction film as an object. Juxtaposing video with film stills and historical archives, Powers creates a compelling argument that the visual program of the blockbuster can and should be understood in terms of the art, architecture, and politics of Cold-War America. An essay by Powers published in Triple Canopy, with important editorial contributions by Colby Chamberlain, was the genesis of the project. Composer Luke DuBois created the film’s original score.

Magnasanti vs. Slave City

Holy smokes, this is so incredible. Vincent Ocasla beat (sic) Sim City by spending three years designing and building Magnasanti, a six million person city that runs flawlessly (sic, again, obv) for 50,000 years. The YouTube video is ominously awesome.

It reminds me of Joep van Lieshout’s creepy totalitarian project, Slave City. I’ll find some links when I get off this blog-hostile iPad.

Originally called Call Centre, Van Lieshout began designing Slave City, a theoretically self-sufficient, eco-neutral, and highly profitable city of 200,000, in 2005. Reg wrote about Slave City on the occasion of Tim Van Laere Gallery’s 2006 show. If I remember correctly, Joep talked about Slave City a lot during his 2007 Tate Artists Talk.

Slave City itself is a little reminiscent of Pig City, the provocatively dystopian proposal to concentrate the Netherlands’ sprawling pork industry into highrise farms, which was floated in 2000 by Joep’s Rotterdam neighbors, MVRDV.

This is how we end up building The Matrix, people; one cautionary-but-a-little-too-enticing concept study at a time.

interview with Ocasla: the totalitarian Buddhist who beat Sim City [viceland via @jadabumrad]

The Civilian Camouflage Council

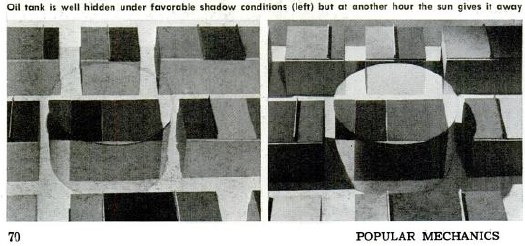

December 1942, the US is at war, and everyone is tinkering in his basement, doing his part to protect the civilian and industrial landscape against the latest technological threat: aerial photo reconnaissance. From a lengthy, fascinating article in Popular Mechanics:

But today civilians around the world, particularly in the United States where the home workshop abounds, are beginning to do what nature forgot: fooling the spy in the sky with camouflage. A recent estimate indicates that more than 5,000 civilians have taken up camouflage research as a serious occupation.

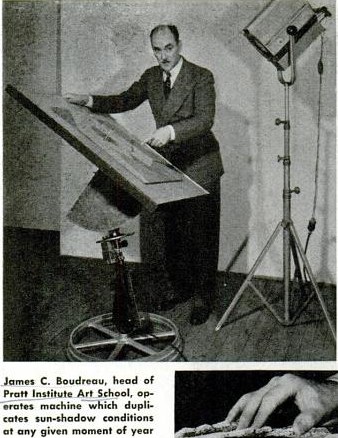

That number did not include the teams of artists and theater designers and architects at various museums, or much of the art and design departments at Pratt, where dean James Boudreau could be seen demonstrating Pratt’s “sun machine,” which “duplicates sun-shadow conditions at any given moment of the year”:

“Since military camouflage is well in hand,” Pop Mech said reassuringly, and while “the government has not yet completely coordinated local civilian camouflage efforts,” the field is “wide open to patriotic and inquisitive minds.”

There followed a primer on basic camo strategies–including Dazzle painting–shadow and lighting, and photo mapping, all illustrated with photos of people photographing painted and sculpted models as if from the air.

Though they were namechecked, the groundbreaking, eerily prescient work of New York’s Civilian Camouflage Council [!] went unremarked.

Founded by Long Island architect Greville Rickard, the CCC had, with Pratt’s Boudreau, organized an exhibit of industrial camouflage designs at the Advertising Club, which opened December 8, 1941. In Dec. 14 review of the show titled, “Art In A Practical Service To War,” the NY Times’ Edward Alden Jewell said,

This is a show that every one should see. It illustrates vitally important defense methods as applied to needs that are immediate all over this country. A fortnight ago such needs might have been looked upon by the public as remote and more or less theoretical. Such is the terrible swiftness with which events have moved, they must now be recognized as of prime consequence.

Jewell then went on to discuss shifts in camouflage as they related to art history:

The progress of the art of camouflage in, say, the last three decades seems not altogether unrelated to certain “key” phases in the development of painting and sculpture. As I understand it, principles oof Impressionism and even of Cubism were examined and to some extent adapted to the uses of the camoufleur during the last World War. But in contradistinction to this trend, teh present trend parallels what in art parlance we designate as Naturalism. It may be said that in the year 1941 camouflage, whether industrial or strictly military, goes with marked singleness of purpose “back to nature.”

The show also included contributions from Stanley McCandless, then at Yale, who is known as the father of modern stage lighting.

In August 1942, the CCC-sponsored Pratt exhibit had been combined with military material and restaged at The Museum of Modern Art. Organized by The Modern’s Carlo Dyer, “Camouflage in Civilian Defense” was one of at least eight war-themed shows The Modern organized and sent on tour in 1942. Doing its part to beat back isolationism!

Fooling the Spy in the Sky, Pop Mech Dec. 1942 [via google books]

One Makakai, Acrylic Pressure Hull, Shipped, Please

I saw a citation in a footnote somewhere, but in the three weeks it took for the Design Review: Industrial Design 23rd Annual, 1977, to arrive, I’d completely forgotten why I’d ordered it.

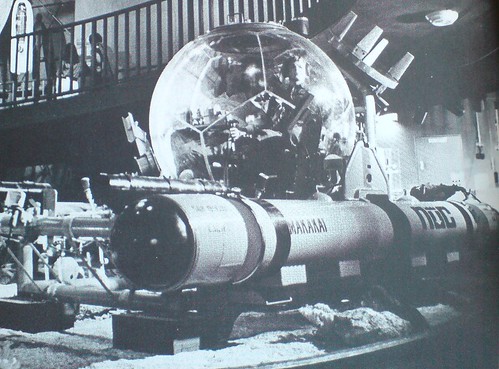

No matter, this insane image of a Makakai deepwater transparent hull submersible (THS) is worth the $2+shipping.

There’s a lot less info online that I’d expect for such an awesome-looking rig, but according to Globalsecurity.org, it was developed at the Naval Undersea Research And Development Center [NURAD?] in San Diego:

Two standard spherical hull designs were available; (a) 66 inch outside diameter and 2.5 inch thickness for 600 ft. operational depth and (b) 66 inch outside diameter and 4.0 inch thickness for 1000 ft. depth. The hulls were fabricated by adhesive bonding of 12 thermoformed spherical pentagons, two of which incorporate metallic hatches.

I’ve just added it to my military industrial geodesic sphere government surplus save search list on eBay. Competing bidders, be warned.

Deep Submersible Rescue Vehicle [globalsecurity.org]

Beckstrand Lodge, 1950

I saw the mention while searching for something else, shocked that I’d never heard of it:

“Beckstrand Lodge, UT, 1950”

A quick search, and there’s no information, no photos, no documentation, no nothing.

Some fruitless Google Map surveying, then some offline inquiries, and sure enough, whatever piece of land was called 60 years ago, it’s not called that anymore on any official records.

So I called a couple of people whose jobs–really, I’d think it’s their job to know this kind of thing. One charged me $10 to tell me what I already knew [see above]. The other thought it was an April Fool’s Day joke. So I began researching myself.

Dr Grant Beckstrand, noted oncologist, and his wife Mildred had a house in Palos Verdes, built in 1940, but it turns out he’d been born in Utah. And you know how it goes: you can take the boy out of Utah… So they built a little place to use for hunting.

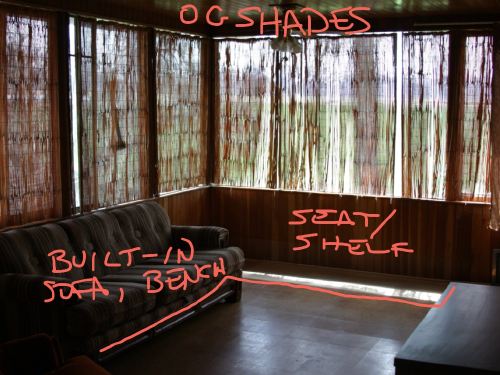

The current owner remembers it being built, though. Said that back then, no one in the county had money to build anything at all, much less a vacation home, complete with imported Italian cork tiles:

The Beckstrands passed away without any kids. They set up the Beckstrand Cancer Foundation with their money. The lodge changed hands a couple of times, but it’s settled down, pretty much as it was, same as the Beckstrands left it, right down to the cushions:

And curtains:

An elderly man from a nearby [sic] town, run out of money, moved in for a couple of years. Helped keep the place up, but had a hard time with the built-in sofa in the living room, so he took that out. Same with the counter by the front door:

Some Pointers, Or What To Do With Neutra’s Gettysburg Cyclorama Center?

The Park Service’s stated goal for Gettysburg is the “rehabilitation” of the battlefield to its 1863 condition by removing modern structures like Richard Neutra’s Cyclorama Center [designed, it should have been noted a long time ago, with Robert Alexander] and the visitors center next to it [already gone] which are built on “hallowed ground.” Which is not quite so simple.

In Gettysburg: memory, market and an American shrine, his 2003 history of the ongoing cultural battle over the site and its meaning, Jim Weeks looked at the controversy over the Park Service plan to create a big, new privately operated visitor center/museum offsite. This wasn’t “Disneyfication,” it was, in the words of John Latscher, the Gettysburg superintendent who spearheaded the deal, “re-sanctifying” the battlefield. [emphasis added on the tiny but powerful rhetorical device that automatically transforms anyone who disagrees into John Wilkes Booth.]

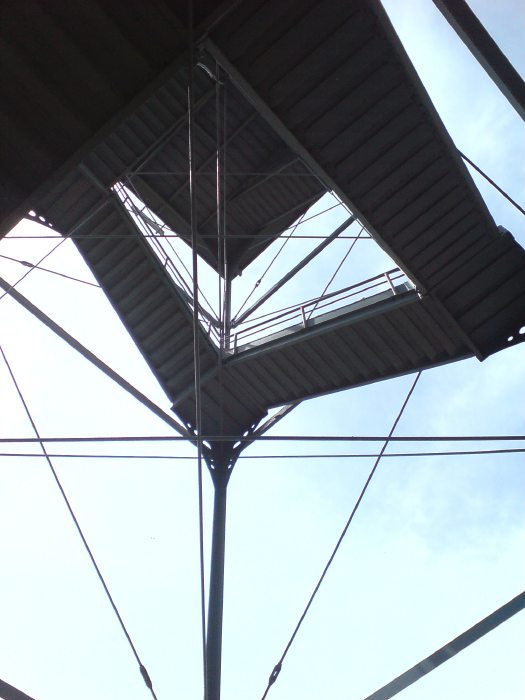

The rehabilitation/re-sanctification plan to remove post-1863 structures does have some loopholes: anything in the middle of the battlefield but on private land across the street, as long as it serves popcorn chicken and/or deliciously dark chocolate pies for a limited time only; the 1392 or 1600 markers and monuments placed by “the veterans themselves,” or whomever; and the three remaining observation towers the War Department built.

Let me go on record that, should it ever be threatened with demolition, I will email every architect and journalist I know to save the observation tower on West Confederate Avenue; that thing is a freaking masterpiece. Let’s get that out there right now, because I don’t find much information or discussion about it at all. [Here’s another of the three, dated 1895, the year the War Dept took charge of the Memorial Park, which is super-short. It looks like there were structural problems, and it was chopped in 1960. Note that it wasn’t torn down completely; I think I’ll come back to that in a minute.]

What do you get for your steep, 6-7 story climb up the steel cage? A great view, of course. But also understanding. Context. Orientation. It’s the place where people tell stories of troop movements and battle strategies. There is much pointing. All across a vast landscape like this, we saw people orienting themselves, spotting landmarks, and telling stories. They were mapping the action and the meaning, translating history onto the site in front of them.

Weeks’ book notes that observation points have been a popular and vital feature of visitors’ experience at Gettysburg from very early on. Some are natural spots, like the promontories of Little Round Top and the Copse of Trees at Cemetery Ridge. Some were built, like Round Top Park, the War Dept. towers [there used to be five], the Pennsylvania State Monument–and the Cyclorama Center. The biggest observation tower, built on private land, was seized and destroyed in 2000 after an intermittent, 26-year legal battle. Weeks draws the connection between the dioramas and orientation maps, the cycloramas–almost all of which had their origins in commercial/entertainment enterprises–and the site itself; arguably, facilitating this mental transition from representation to site was the major justification for placing the Cyclorama so close to its focal point, the top of Cemetery Ridge, in the first place.

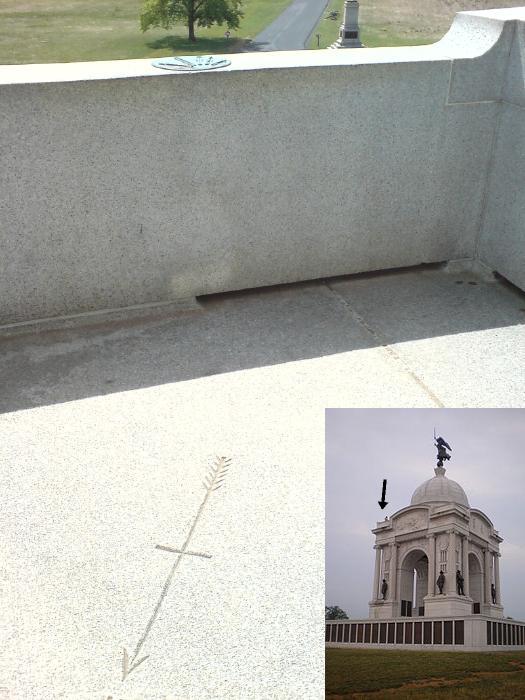

One common feature of these observation points is the orienting device: arrows pointing toward key sites or events. Here is the welded steel plate on the War Dept tower:

Which was the third one I noticed, after [1] the compass mark handcarved into the granite floor and [2] the incredible cast bronze plaques on the parapets of the Pennsylvania State Monument. [Which, by the way, is a gigantic Beaux Art mess, a Columbia Exposition knockoff whose looming, continued presence exposes the whole idea of re-creating the 1863 battlefield to be little more than conceptual cover fire to advance a subjective set of pre-determined alteration strategies.]

These arrows, on these structures, point, I believe, to a possible future for Neutra’s Cyclorama: restore and reconfigure it as an observation and orientation platform for Cemetery Ridge. Neutra already included an observation platform and ramp [see house industries’ photo below]; adapting the empty rotunda for observation would hew close to the building’s original function on its original site, while minimizing the loss of Neutra’s and Alexander’s key design elements.

Then there’s precedent: the Park Service’s stated strategy of 1863 rehabilitation nevertheless preserves several post-1863 observation structures, including the unassailable Pennsylvania Monument and three of the five towers apparently installed by the War Department at the founding of the Memorial Park. One is apparently historical and/or functional enough to preserve even after being truncated to just one story up–roughly the same height as the Cyclorama’s existing deck.

A Cyclorama Observation Platform would also offer something completely unique: accessibility. All other observation spots we saw involved stairs, curbs, or uneven wooded trails. [The Pennsylvania Monument’s vantage point is reached by a single, awesomely treacherous spiral staircase lined with stamped bronze paneling that’d do a SoHo loft ceiling proud.] Much of the battlefield itself–and thus the monuments scattered across it–quickly becomes inaccessible to disabled or wheelchair-using visitors.

An entirely ramp-based observation structure would enhance the battlefield experience for millions of visitors who would otherwise be confined to their cars. [Oh, look! Neutra’s already got two ramps built right in! image above: houseindustries.com]

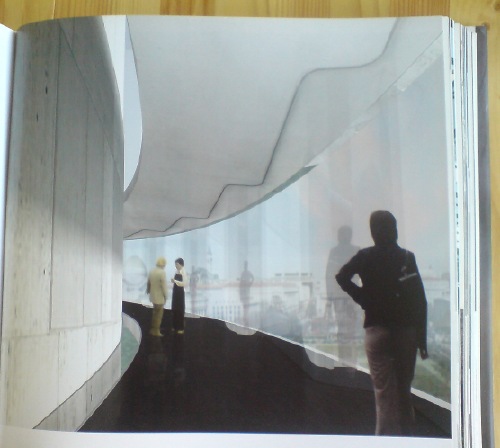

In fact, a speculative observation platform proposal has already been floated. The Boston-based architecture firm CUBE design + research used Neutra’s Cyclorama Center to illustrate a range of alternatives to strict historical preservation. One idea [above]: turning the Cyclorama as “informant” and “information hub,” by making strategic, view-framing cuts in the rotunda. It’s a pretty radical alteration, the kind of thing that keeps traditional preservationists up at night. And as proposed/rendered, I think many of Cube’s solutions go way too far. But they’re spurring discussion, not answering an RFP, and in that, they succeed.

Piercing Neutra’s rotunda in places might still work, perhaps in combination with another of CUBE’s suggestions, to place the Park Service’s historic electric relief map in the building. Or perhaps a large-scale relief map could be made for blind visitors to gauge the scale and detail of the terrain. In either case, a multi-sensory narrative program could be devised that integrates such artifacts with views out of the building onto the actual battlefield. [Something like the light and sound effects on the new Cyclorama installation, which seem to be state-of-whatever-art-these-sorts-of-things-are.]

Another possibility just came to me this morning: the 2006 proposal Olafur Eliasson made for the Hirshhorn Museum, a similarly love-to-hate, modernist concrete barrel on a major civic site. Eliasson proposed wrapping Gordon Bunshaft’s building with a suspended glass walkway that afforded sprawling views of the National Mall, something akin to the exterior escalator tubes at the Pompidou. [images: from the bookshelf-straining insanity that is Taschen’s Studio Olafur Eliasson: An Encyclopedia.]

Maybe an information-filled ramp could spiral up the inside of Neutra’s rotunda–a history of the wounded, perhaps, and their heroism and their tales of endurance and remembrance–and then let visitors out to wind their way down the outside, where they could then descend along the original ramp onto the battlefield itself. At least as far as their wheelchairs can take them.

The Park Service and Gettysburg Foundation claim the current battlefield rehabilitation plan provides great “environmental benefits,” even as the courts find they have failed to undertake the basic impact studies required by law.

Worse than this, though, is the active, and ongoing denial of the equality of us all–by denying equal access to key parts of the battlefield experience, such as observation platforms–on the very battleground of freedom made sacred by the sacrifices of life. And limb.

Next: Observations from/on Towers and The Wound Dresser, set in stone, rest stops on the journey Toward a Cyclorama-shaped Gettysburg Memorial to The Wounded

The Eternal Sunshine Of A Spotless Battlefield

So a quick recap: the National Park Service is determined to demolish the Richard Neutra’s Cyclorama Center, built at the Gettysburg National Military Park in 1961. It was designed to house Paul Philippoteaux’s massive panoramic painting, made in 1884, depicting Pickett’s Charge, and it was sited on Cemetery Ridge, the central target of the assault and the focal point of the cyclorama. [above, a House Industries view from the narrow observation deck and ramp to the battlefield back toward the rotunda, which is largely hidden by trees.] The Cyclorama Center and a nearby Visitors Center were built as part of the Park Service’s Mission 66 program, a 10-year strategic plan to upgrade visitor and interpretive facilities and to make historic sites more car-friendly.

But that mission, and the many modernist-style buildings and structures it spawned, are viewed with disdain by the current Park Service; just as mid-century architecture is becoming eligible for historical preservation status, and as scholarship and critical appreciation is picking up, Mission 66 buildings are under threat of destruction or major alteration in line with current tastes and trends in exhibition and interpretive practice.

As it turns out, the battlefields of Gettysburg have been the site of many strategies of remembrance, commemoration, and visitor/tourist experience. More than 1,600 structures, buildings, sculptures, markers, and memorials have been erected on the site over the last 147 years, not including the railroad station, dance hall, casino, brothel, or souvenir photo studio which were on-site for the massive 50th anniversary/veterans reunion in 1913. Which means that whether officials choose to acknowledge it or not, there is a constant debate at the site about significance, appropriateness, meaning, experience, memory, and history, and that bears directly on the fate and future of the Cyclorama Center.

When I asked about the Cyclorama Center at the information desk in the sprawling, new, historicist, farm building-looking visitor center last weekend, my question was met with brusque disinterest. “It’s just a round building, nothing significant about it,” said the Friends of Gettysburg volunteer.

The Friends of Gettysburg merged with the Gettysburg Foundation in 2007. For almost two decades, the Gettysburg Foundation had helped the Park Service develop and realize the Gettysburg Battlefield Rehabilitation Project, the stated goal of which is to “rehabilitate the land to as close as possible to its 1863 appearance,” in order that the site’s “important physical qualities [will help] tell the story of the Battle of Gettysburg.”

A great deal of a 2007-8 project summary [pdf] talks about altering the terrain–removing or planting woodlands, replanting orchards, redividing fields, repairing roads and paths–which will generate vast “environmental benefits.” “The rehabilitation effort will preserve nature as it preserves history,” promises the Foundation.

But the language makes a sharp shift when discussing parts of the Cemetery Ridge Project:

…in the 43.5-acre area of Cemetery Ridge, many of those features have succumbed to natural vegetative growth and other aspects of evolution. The Cemetery Ridge project was initiated to rehabilitate this highly significant land. This project involves:

- Removal of the original Gettysburg visitor center building, which sits on the hallowed ground of Zeigler’s Grove. This older structure is being replaced by a new 139,000 square foot Museum and Visitor Center, which will open in April 2008. The new center is situated on an area that saw no major battle action, about 2/3 of a mile from the former park visitor center.

- Removal of the 1962 Cyclorama building and the parking lots and roads associated with the Cyclorama building and original visitor center building–all of which lie on soil where nearly 1,000 soldiers fell.

…

- Relocation of seven Civil War monuments to the sites where they were originally placed by veterans of the battle. These monuments were moved during the construction of the 1962 Cyclorama building and surrounding parking lots. [emphasis added]

I’m sure that the Foundation is not impugning President Eisenhower or the previous generation of Park Service officials who paved over the fallen soldiers’ hallowed ground in the first place. And I’m sure that the parking lot set to remain on the site will be only on the unhallowed parts, just like the roads that traverse the Ridge now.

And I’m sure that it wasn’t the Park Service’s fear of antagonizing the local business community that kept them from including the eventual removal of General Pickett’s Buffet, Colonel Sanders’ place, and McDonald’s [above, via jetsetmodern] from the hallowed ground across the street where several thousand other soldiers surely fell.

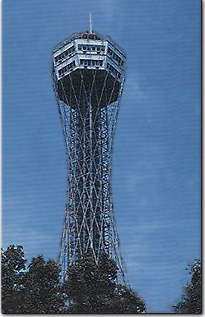

After all, the Park Service had no problem using eminent domain to seize and demolish the Gettysburg National Tower [left]. Built in 1974 on private land adjacent Cemetery Ridge, the controversial 307-ft tower was destroyed with great fanfare in 2000.

After all, the Park Service had no problem using eminent domain to seize and demolish the Gettysburg National Tower [left]. Built in 1974 on private land adjacent Cemetery Ridge, the controversial 307-ft tower was destroyed with great fanfare in 2000.

And then there’s the to-be-resited monuments, part of the “largest collection of outdoor sculpture in the world,” which were not, of course, present in 1863, but which were “originally placed by veterans of the battle.” Which is, of course, the second-most-irrefutable argument after “hallowed ground where soldiers fell.” [I’m sure the hundreds of additional markers placed by the War Department, and all the other non-veteran-related structures that have accreted on the site–including the incredible WWII-era, government-issue observation towers like the one along the Confederate line–will be rehabilitated away in Phase II.

Next: Some Pointers, or What To Do With Neutra’s Gettysburg Cyclorama Center?

‘The Largest Collection Of Outdoor Sculpture In The World’

The significance of the battle at Gettysburg was seized upon almost immediately, both for the vast scale of the casualties, but also because of the strategic and symbolic importance in the North of repelling the Confederate incursion. Dealing with overwhelming death, destruction, and injury immediately overwhelmed the town, and thousands of visitors streamed in to find and help family members.

Efforts to memorialize the battle and secure the battlefield also began immediately. Lincoln’s address just four months later was, after all, at the dedication of the National Solders Cemetery on a fought-over piece of land. Within weeks, historian John Bachelder began interviewing officers and attempting to pinpoint key movements and events leading up to and following the battle. And after the war, he prepared a comprehensive, if unreconciled, report of thousands of interviews and onsite surveys with survivors. Land acquisition also kicked in immediately, and a Gettysburg Battle Memorial Association was quickly formed. Because of its proximity and well-developed transportation, Gettysburg quickly became a popular tourist destination.

Memorials were placed on the battlefield to mark the sites of action engaged by individual regiments in the 1870s, but the pace picked up in the 1880s, as the 25th anniversary of the battle approached. As Wikipedia has it, survivors of the battle returned to the land to remember their individual and collective experiences, and to mark their significant events–battles, movements, victories, deaths–on the site itself:

For the Union side, virtually every regiment, battery, brigade, division, and corps has a monument, generally placed in the portion of the battlefield where that unit made the greatest contribution (as judged by the veterans themselves). Most regiments also have boundary markers placed to show their positions in defensive lines or in the starting lines for their assaults. The placements are not always definitive, due to sometimes faulty memories of the veterans or to the problems resulting from attempts to represent multiple days of battle fought on the same ground, most notably Cemetery Ridge.

When the site was transferred to the War Department, over 1,600 bronze markers were erected, based on the official history of the battle [not Bachelder’s].

The non-profit Gettysburg Foundation calls it “The largest collection of outdoor sculpture in the world.” But it’s even more than that. All these structures, sculptures, and monuments fill the landscape and connote a previous generation’s specific strategy of remembrance. And each, no matter how subjective, seemingly incidental, or retrospectively problematic, now bears the weight of that generation’s history.

Even a fence. At some point in the past, a section [reportedly a quarter of the original size] of the Copse of Trees which was Gen. Lee’s chosen focal point for the Confederate attack was rendered sacred, like a home cemetery, and fenced off from public access. The generic 19th century wrought iron fence, damaged by a fallen tree, but set for restoration, is visible behind this c.1880s War Dept. plaque for the Fifteenth Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry:

The position of this regiment in line of battle

is marked by its monument

235 yards due south.

It charged up to this point and attacked Pickett’s

division in flank as his troops were coming

over the stonewall.

The battlefield sprouted other structures alongside these markers and memorials. In 1884, at the height of the Cycloramas’ popularity, the railroad laid tracks across the field of Pickett’s Charge to its new Round Top Park, an entertainment center on Little Round Top. A casino was added in 1913, the year the Boston Cyclorama came to Gettysburg in time for the Great Reunion, a conciliatory event that brought over 50,000 Civil War veterans together at Gettysburg. The veterans from all states re-enacted Pickett’s Charge, which ended with the exchange of handshakes and speeches. [It wasn’t until 1939, after the 75th anniversary, that the amusement park’s structures, and the tracks themselves, were removed.]

After WWII, Pres. Eisenhower’s development of the interstate highway system was coupled with the National Park Service’s Mission 66, a 10-year strategic plan to increase the accessibility of its sites to cars, and to provide high-quality interpretive services for its increasing throngs of visitors. Eisenhower took particular interest in Gettysburg where, while president, he decided to purchase his first home, a farm, precisely because it was built on battlefield ground. He retired to the house in 1959; it is now a presidential memorial within the expanded Military Park.

Thus is the victory of World War II, and the postwar boom, and our modern entertainment experience culture inextricably intertwined with the memorial to the bloodiest battle of the Civil War. And now we have a brief movie lesson by Morgan Freeman, and an economy where the only jobs in town that don’t involve wearing a hoop skirt are selling Civil War Orange Fudge at the Gettysburg Outlet Mall. But as the railroads and casinos and dance halls–and the Cyclorama itself–show, this spectacle- and souvenir-centered culture is not a transformation or desecration, only an upgrade in technology.

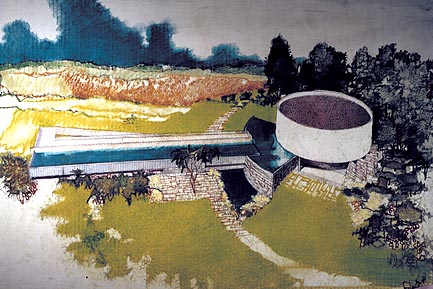

Cyclorama Center rendering, Richard Neutra, via mission66.com

But Mission 66 was too much of a good thing. The Park Service has long strained under its visitor volume; some structures were outgrown, others left to decay because of deferred maintenance. Many, like Neutra’s Cyclorama, were built in a mid-century modernist idiom, which preservationists have been slow to preserve, and which the Park Service [currently] hates. According to Mission 66 architectural historian Christine Madrid, the Park Service considers the modernist structures “a post-war mistake.” And they bridle, not only at their historical significance, but at the very notion that the Park Service is not the author and custodian of history, but just the biggest of its many actors.

Next: The Eternal Sunshine of a Spotless Battlefield

On Richard Neutra’s Cyclorama Center, Or Gettysburg Memorial: The Making Of

We just got back from a weekend trip to Gettysburg, PA, and I was not quite prepared to be so fascinated by it. Gettysburg the town was attacked the Confederate Army in the Civil War partly because of its symbolic value [as a Northern target], but also because so many roads converged there. It turned out several of the meandering paths I’m interested in converged there, too.

Without knowing exactly where it was, I was interested in seeing the closed Cyclorama Center, designed in 1962 by Richard Neutra. In 2008, after relocating the Cyclorama itself–one of four extraordinary 359-ft long panoramic paintings made in the 1880s by Paul Philippoteaux [three remain]–to a new Visitors Center, the National Park Service began trying to demolish Neutra’s Cyclorama Building. Neutra’s son Dion and other preservationists are contesting this plan in court.

Well, it turns out the Cyclorama’s right on Cemetery Ridge, near the Confederate Army’s key attack on the center of the Union line. Which turns out to make sense, because that site was the focal point Philippoteaux chose for the paintings. This Cyclorama was on display in Boston for many years, until it was relocated to Gettysburg the town in 1913. The Park Service bought it, restored it, and then re-sited it to the very site it depicted, in time for the 100th anniversary of the battle.

The Park Service’s reasons against keeping the Cyclorama Building are partly logistical–it couldn’t accommodate the current number of visitors and cars; partly technological–the state of the Cyclorama art now involves multimedia light and sound elements, as well as 3D dioramas, which were apparently present in Boston, but not in subsequent installations. But its main argument is curatorial–it’s now considered inappropriate to place such interpretive structures directly on the site itself. The contemporary building thus thwarts their attempt to restore the battlefield to its pastoral, pre-1863 condition.

The first argument is undoubtedly true, but it doesn’t preclude the NPS from adapting the building to some kind of other, lower-impact use. The second argument is true, too, and I’d guess that they feel they’re getting the most out of their Cyclorama Experience now. Plus they now get to charge $10.50 for a ticket.

It’s the third argument that turned out to be so confounding and complicated, because the battlefield is literally jammed with markers and structures, not just monuments and memorials, that have been put there by successive generations as part of the remembering and memorializing process. The Cyclorama and its building are among the most important chapters in the post-war history of Gettysburg, and the Park Service’s plan to destroy the building would be highly questionable even if it hadn’t been designed by one of the country’s most well-known modernist architects.

Just about a month ago, a federal judge found that the Park Service had failed to study or consider the impact of demolishing Neutra’s building, which they had lobbied to keep off the National Register of Historic Places.

I think I’ll be breaking this up over several posts.

Next: ‘The largest collection of outdoor sculpture in the world’

Otto Piene’s More Sky

Alright, all y’all who didn’t tell me about Otto Piene’s classic of the books-written-in-longhand era, More Sky: what else have you been hiding?

Alright, all y’all who didn’t tell me about Otto Piene’s classic of the books-written-in-longhand era, More Sky: what else have you been hiding?

Otto Piene literally opens up new horizons here in both art and art education. His book is a plea for more scope, more space for art–for making public property artful and making art public property–for freeing the arts from the tight economic bonds that give the curators and the collectors a near monopoly. He writes, “The artist-planner is needed. He can make a playground out of a heap of bent cans, he can make a park out of a desert, he can make a paradise out of a wasteland, if he accepts the challenge…. In order to enable artists of the future to take on planning and shaping tasks on a large scale, art education has to change completely. At this point art schools are still training object-makers who are expecting museums and collectors to buy their stuff….”

The first part of More Sky covers “things to do” arranged alphabetically, A-M (Piene will take up N-Z some other time.) Like city planning, clothing, collaboration, electronic music, elements, engineering or government, graffiti, graphics, green toad jelly.

All these notes cohere into a larger statement in support of an environmental art for social use, the interaction of art and architecture and the city and the open landscape, a total ecological and elemental aesthetics.

The last part of the book, “Wind Manual,” gives a practical demonstration of things to do in just one area. But it’s a big one–the whole sky–and a lot can be done in it, making use of the wind; making human clouds, rain, rainbows; and making things that fly and float. This section is made up almost entirely of full-color illustrations of some of the things that man the artist can do to purify the skies polluted by man the money-maker and rendered fearsome by man the war-maker. The illustrations show different kinds of flags, banners, ribbons, wind socks, wind sculptures, riggings, kids and other things.

The first part was written plain, in the Spring of 1970, with no trace of artspeak jargon. And the second is plainly drawn and colored. (Piene is more versatile than most contemporary artists: he can do his abstract light-ballet things, and he can span rivers with man-made rainbows, and he can draw a recognizable picture of a bull.) The “Wind Manual” was originally drawn for instant use in schools and colleges in Pittsburgh–it was created as part of a Piene-guided public art project called Citything Sky Ballet.

The MIT Press

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Cambridge, MA 02142

Otto Piene’s More Sky is available the 1973 edition with the fun, blue cover, and a print-on-demand version with a boring black cover. So heads up when you buy. [amazon]

The Judd Conference

I cannot go to Oregon for the weekend, but I would pay cash money right here and now to watch a livestream of the Judd Conference, the Univerity of Oregon’s day-long exploration of Donald Judd’s fabrication methods. The official title is, “Donald Judd Delegated Fabrication: History, Practice, Issues and Implications “:

From the outside a Donald Judd piece is seamless, hiding all traces of its construction. But behind the final piece is a rich history of the artist’s intent and his method for fabrication. Join us for a groundbreaking discussion of Judd’s art, lead by contemporary art scholars and Judd’s longtime fabricator, Peter Ballantine. The day-long conference in Portland, Ore., will look at Judd as an icon of the American minimalist movement, as well as issues of authenticity and fabrication that continue to have lasting implications for artists today. In addition, the conference will explore the artist’s connection to the Pacific Northwest, where he created a site-specific piece in 1974 for the Portland Center for Visual Arts (PCVA).

Arcy Douglass is running a Judd Conference blog, and of course there’s a Judd Conference Twitter [@juddcon].

Douglass also wrote an article a little while ago about Judd’s large-scale plywood work executed at the Portland Center for Visual Art in 1974. Like the incredible Plywood Slant Judd installed at Castelli in 1976 [which was re-created at Paula Cooper in 2001], it was a site-specific, architectural construction determined in part by the dimensions of the plywood itself.

On second thought, maybe it is best to be there in person. Not just so you follow Peter Ballantine around as he visits his secret local sources for vintage plywood and Oregon Pine. But to get some straight answers about what the hell was going on with this corner of the PCVA installation. Great Caesar’s ghost! [via artnet]

Art Fleet: Domes & Trucks & Art Things That Go

While researching the National Gallery of Art’s Barkley L. Hendricks paintings, which were purchased by J. Carter Brown with money from Michael Whitney Straight, I came across one of the crazier space-meets-art moments in the history of exhibition design: Art Fleet.

While researching the National Gallery of Art’s Barkley L. Hendricks paintings, which were purchased by J. Carter Brown with money from Michael Whitney Straight, I came across one of the crazier space-meets-art moments in the history of exhibition design: Art Fleet.

In an amusingly transparent move to manage his own complicated story, Straight wrote a biography of Nancy Hanks, the founding chairwoman of the National Endowment for the Arts, who had been appointed by Richard Nixon. [Straight himself had been approached to found the NEA by the Kennedy administration, at which point, he disclosed his history as a KGB spy. He became the deputy chairman, instead, a post which did not require Senate confirmation.]

Anyway, Art Fleet. We begin in San Clemente, 1970:

In the same spirit of loyalty to the president who had appointed her, Nancy committed the Endowment to supporting a project entitled Art Fleet. She had asked the president, when she met with him in San Clemente, what he would like the Arts Endowment to do. He had replied that “it was extremely important to get the arts out into the country.” Nancy had agreed. She was reminded of the technical problems involved in moving art masterpieces around the nation. She dismissed them. As Bill Lacy, our program for Architecture and Environmental Arts, recalls, “Nancy contended that if we could put a man on the moon, we could surely send the Mona Lisa around the country.” [p.149]

Surely, why not, but seriously, why?

And what do you want to do with the Mona Lisa again?

Continue reading “Art Fleet: Domes & Trucks & Art Things That Go”

Alcoa Forecast: Spheres Of Tomorrow

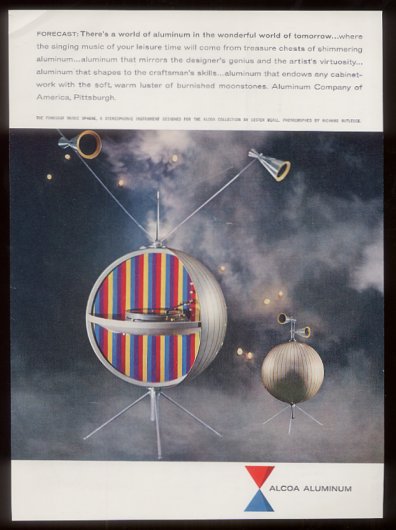

They’re both under-known, and so they probably deserve their own posts, but the uncanny similarity of these two Alcoa Forecast program designs requires me to put them together.

Greta Magnusson Grossman was a Los Angeles-based Swedish industrial designer. According to the notes at the 2008 Drawing Center exhibition of her never-before-seen technical drawings, she was highly influential on her fellow Southern California colleagues in the 1950s-60s, including the Eameses.

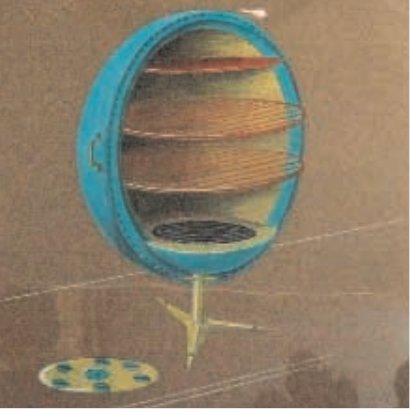

That show included a sketch [above] for the personal aluminum oven she designed for Forecast. A small photo of the wacky, ball-shaped oven appeared in a collaged Forecast ad in the Dec. 28, 1959 issue of LIFE Magazine.

[update: whaddyaknow, the new blog The Modernlist reports that the Arkiteturmuseet in Stockholm has the first-ever Magnusson Grossman retrospective right now, through May 16. Definitely check out that crazy Grossman House.]

Graphic designer Lester Beall, meanwhile, is better known, at least by my criteria: I recognize his awesome, constructivist-style photocollage posters for the Rural Electrification Administration from MoMA’s design collection. His portfolio site says he designed the Music Sphere for Alcoa in 1956, which seems remarkably early.

An unsourced tear sheet for a Forecast Collection ad on eBay says it’s from 1969, which is remarkably late. I’m going to guess it’s really 1959. But the real question is why the future doesn’t have even a tiny fraction of the giant, shiny aluminum ball-shaped appliances we were promised?

“Aluminum that mirrors the designer’s genius and the artist’s virtuosity”? “Aluminum that endows any cabinetwork with the soft, warm luster of burnished moonstones”?? I think we have found Project Echo’s official stereo!