When I first came across the pixelated Dutch landscapes on Google Maps , I imagined the polygonal camo distortions hovering over the sensitive sites. From the ground, I thought, maybe it looked like a Gerhard Richter overpainted snapshot.

But now I think it looks more like the bright, beautiful gouaches by Louise Belcourt which Sharon featured on Two Coats of Paint recently.

Images: Louise Belcourt’s place in the world [twocoatsofpaint.com]

Category: art

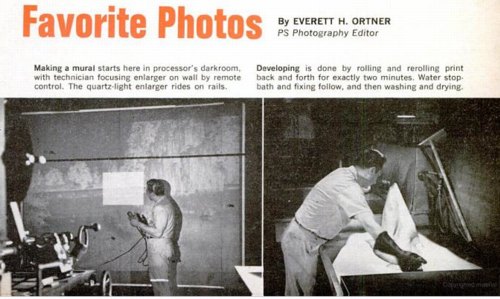

Where To Make A Steichen-Style Photomural: Compo Photocolor

While trying to find out where and how to make a photomural, or at least how they used to make them, I found this slightly ridiculous 1966 Popular Science article about making photomurals in your very own home. And how you basically shouldn’t do it, but instead just mark up a negative and send it off to a photo enlarger somewhere.

Someplace like–hey-o!–the outfit mentioned in a caption, “Compo Photo Color, 220 W. 42nd St., NYC, specialists in murals and exhibition prints who did famous ‘Family of Man’ photo show.” And so it comes pretty much full circle, back to the most famous photomural exhibition of all.

So who is Compo Photo Color? Or was. Immediately available references are pretty scarce, but Compo seems to have been in business from the 1950s until the early-to-mid 1970s. Its principals were a German immigrant photographer Richard J. Schuler and Ernest Pile, and it was eventually consolidated into Wometco Photo Services, a division of the Miami-based movie theater owner. But back to the apparent heyday, in the 50s.

In a 2001 interview, photographer Wayne Miller, who was Steichen’s assistant and co-curator on Family of Man, and who contributed the most images to the show, talked about working with Compo on the prints:

Riess: About Gene Smith, can I ask you to repeat the story that I lost last time about asking Gene Smith for a print of that image in The Family of Man?

Miller: Oh yes. In The Family of Man, after we had made our final selections of what pictures we wanted to have in the exhibition we asked some local photographers if they’d like to make the print for us, or would they give us the negative and we ll have the print made by Compo Photocolor in New York. Actually we wanted Compo Photocolor to make all of them so the prints would have a commonality, and they would match the other prints quality-wise. And they were very good technicians.

But in this case, because of Gene, he wanted to make the prints, he didn t feel anybody could make the print as well as he could. And he invariably spent not only hours, but days in the darkroom. In fact, in a Life story he would disappear in the darkroom and return, and you almost– here he was seemingly weeks or months afterwards, with a beard and other things, and with the final prints. And it would drive the Life people mad.

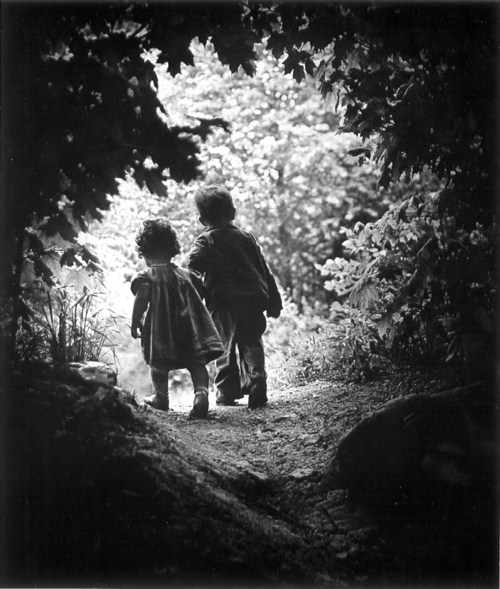

In this case, we had a print that I’d found in the Life morgue of what he [Smith] called “A Walk in Paradise Garden,” something like that, of two children walking out from underneath this frame of bushes. A nice picture, and we wanted to use it at the end of the exhibition. It was going to be about, maybe 30″ x 40″.

I told Gene we wanted to do this and asked him if he’d like to make the print, and yes, he

certainly wanted to make the print. So I arranged for him to get the necessary paper and

chemicals to do this, because his wife Carmen said, “Don t give Gene the money for it, because he’ll spend it on other things.” So after he told me what he wanted, I did get the materials for him. And I gave him a deadline, knowing that he was often not able to meet a deadline, of about three weeks early. So he took this material.

Now the print we had that I’d gotten out of the files had been handled a great deal and it had some cracks in it. It was dog-eared, and it wasn’t a fine print at this point. So at the same time I gave these materials to Gene I sent the print from the Life files over to Compo Photocolor and asked them to make a copy of it, make a negative, and make a print to size. Just so we wouldn t get stuck in case he didn’t come up with the print. Later, when he did do it, we could always replace it. And sure enough, the deadline came and went and we had to put this copy print up on the wall. Because Gene hadn t shown up with his.

A couple of weeks later Gene shows up with these photographs rolled up under his arm. We went up to the museum exhibition space in the morning because the museum didn t open to the public until noon. And I took this print that we had down off the wall, and he unrolled his prints. He had half a dozen of them there, different qualities, and he laid them out beside this print. I was worried about this because I know how he struggles and works so hard on it. He will darken this or lighten that, and he ll use ferro cyanide to bleach little bits. And the delicacies with which he treats a print are just great, they re very great. So I was interested in seeing how it would work.

He laid his out, and he stood back there and looked at these prints. And he walked around a little bit and looked at them some more. Finally, he said, “You know, I think the print you have on the wall is the best one. Let s use that one.” [laughter] So he rolled his up and went along.

That I think points out the fact, I believe, that when you make a photograph, a print of a

photograph of larger than normal size, it picks up a new quality other than one of maybe an 11″x14″ or something. But one like this, maybe 30″x40″, it has a new quality to it.

You know, it didn’t occur to me at all until just now, but Paul Rudolph designed the installation for Steichen’s Family of Man, which was photographed by Ezra Stoller, in January 1955,

the same year Robert Rauschenberg was collaging photos into such giant combines as Rebus. Hmm.

On War-Era Murals

The question or theme or whatever hadn’t crystallized for me, but when Tyler linked to the previous two posts about Lt. Comm. Edward Steichen’s wartime propaganda exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art, he noted that “there’s a lot of art historical work yet to be done on the impact World War II had on art and artists.”

It’s an interesting way to consider my fascination with the aesthetics and paradoxes of photomurals: their apparent historic status as something other than artwork, much like the photographic medium they’re derive from; their powerful scale, which creates a certain kind of all-encompassing viewing experience that is typically associated only with the later works of revolutionary “high art,” namely the Abstract Expressionists; and of course, the abstract and modernist aspects of the images themselves.

I’m not ready to go beyond the grand theory of “this looks like that,” but I keep seeing and finding resonances between photomurals, which were born in the Depression and came of age during WWII, and some of the major developments of postwar art.

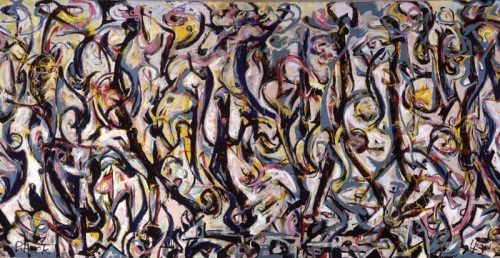

Mural, Jackson Pollock, 1943, collection: UIMA

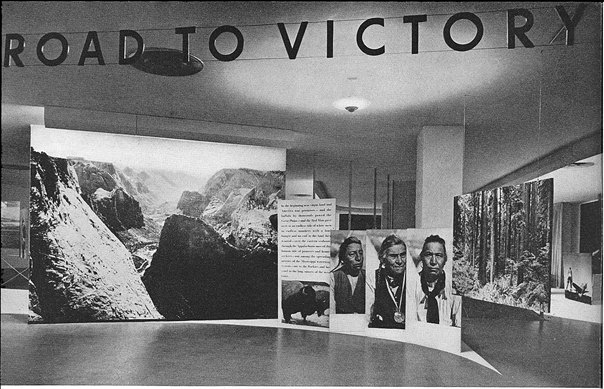

I mean, I’m re-reading Tyler’s interview with Pepe Karmel about Jackson Pollock’s Mural [above], which was painted in 1943, and there are moments where I can’t help thinking about the 15- and 40-foot images in Steichen’s 1942 Road To Victory show:

It’s an important painting for Jackson Pollock because it’s the moment that announces his future as a painter of large, mural-scale paintings that become environments, and furthermore paintings that are in this distinct, all-over style that changes people’s idea of what a painting might be.

…

It’s like Barnett Newman’s Vir Heroicus Sublimis or Pollock’s own Number 1, 1950. You have to be there. You have to be standing in front of it and feel it filling up your field of vision and feel it wrapping around you and feel yourself falling into the field of the painting. If you don’t have that experience first-hand, you won’t get the feeling of the painting.

…

MAN: You talked about how important the painting was in terms of Pollock’s oeuvre. Can you detail why it’s so important to what came next in American and modern and contemporary art?

PK: The next step is off the wall and out into space. In contemporary art that deals with installation as an art form, which comes out of those paintings in 1950 and that comes out of this painting in 1943. It just doesn’t get more historic than this.

It’s truly a kind of unrecognized monument of American art.

Which isn’t to say that Pollock was referencing or even influenced by photomurals, just that both Herbert Bayer’s installation of Steichen’s photos and Pollock’s first epic-scale painting create an overwhelming spatial experience.

Photomurals were out-and-proud propaganda which had connections to filmmaking and the cinematic screen and to world’s fairs, [See Alvar Aalto’s Finnish Pavilion at the 1939 World’s Fair and the Japanese pavilion at the Golden Gate Expo that same year].

Which is one of just a handful of references to photomurals in LIFE magazine’s archives. In a moment of greg.org confluence, LIFE’s most prominent depictions of photomurals are not in museums or world’s fairs, but in political rallies–they are the ur-Sforzian backgrounds. For example, In 1949, FDR Jr. has a giant wall of smiling children behind him at a UAW convention. A chorus line of garment workers kick in front of a selection of “union heroes.” And when he spoke in Boston in 1949, Winston Churchill stood in front of an aerial photomural of the MIT campus [above] which reportedly “confused [the] television audience.”

How To Make A Giant, Steichen-Style Photomural

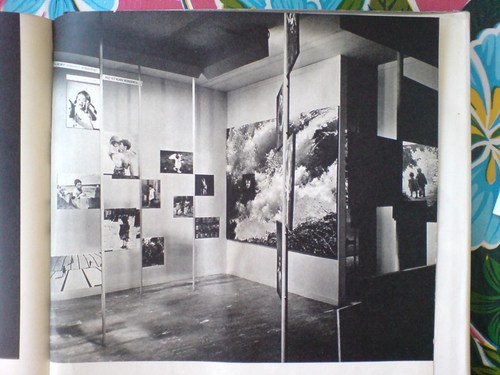

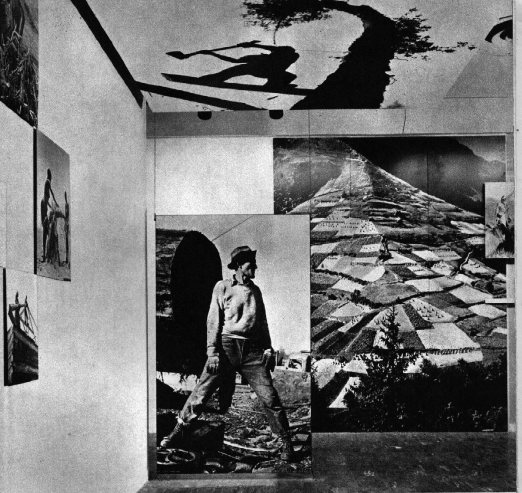

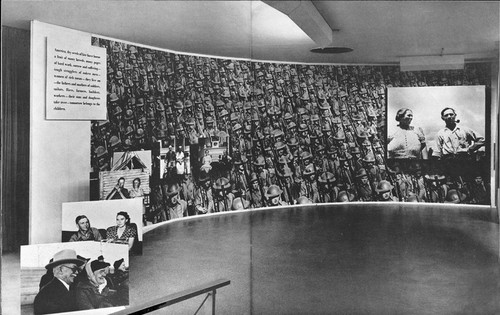

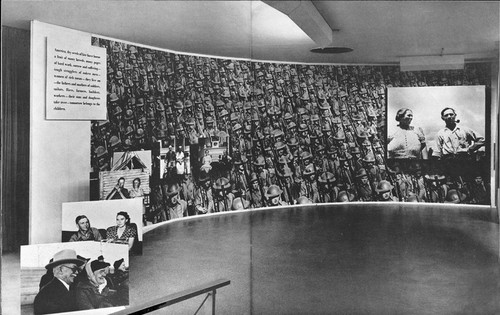

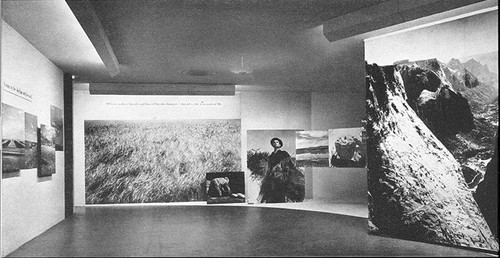

Looking through the installation photos for Road To Victory, Edward Steichen’s 1942 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, I find myself asking two things:

Who took these photos, and how did they make them? [Of course, my real question is usually, Where are they now, which really means, where can I get some? But anyway.]

The first question turns out to be harder to answer than I thought. The MoMA Bulletin for the show states that over 90% of the images are from government agencies, military sources, or wire service/news agencies, but they lack any credit line. It’s slightly amusing that most of the photocredits in the Bulletin turn out to be for the installation photos, not the subject photo murals themselves. If Edward Steichen and Carl Sandburg are the creators of Road To Victory: The Propaganda Artwork, then Samuel H. Gottscho is a rephotographing appropriation artist 40 years ahead of Richard Prince. I’ll have to do some digging for an image checklist in the exhibition’s archives.

As for how these things were made, though, there is actually a footnote for that. And the answer is surprisingly painterly:

To make the large murals, the negatives were enlarged in sections upon strips of photographic paper forty inches wide. The museum wall was first sized, then covered with a layer of wallpaper, next with one of cloth, and then the photographs were pasted on the cloth by paper hangers. The seams were lightly airbrushed, imperfections were retouched by hand, and finally the whole mural was painted with dull varnish to eliminate the glaring reflections rendered by the surface of photographic paper.

Fascinating. Photo wallpaper? Overpainted photomurals?

While large prints in the show were mounted on boards, and some murals were affixed to freestanding walls and panels, others were applied straight to the museum’s walls. Given the anonymity of the images, I’m going to guess that approximately none of these prints or murals survived the exhibition, much less the war.

The Road To Victory And Beyond

So in my ersatz zigzagging through the history of photomurals, I kind of skipped from Edward Steichen’s landmark Family of Man exhibition in 1955, where Paul Rudolph deployed enlarged photo prints for content and experience, as well as architectural elements in his exhibition design; to Capt. Steichen’s 1945 exhibition Power in the Pacific, which featured the work of the US Navy photography unit he commanded; to Steichen’s participation in MoMA’s first photography exhibition ever, a 1932 photomural invitational, which was intended to serve as a showroom for American artists, who faced stiff mural competition during the Depression from south of the border.

Sensing a trend here? Wondering what I missed? Wow. Michael from Stopping Off Place just forwarded me the link to MoMA’s bulletin for Road To Victory, a stunning 1942 photo exhibition that rolls up so many greg.org interests, it is kind of freaking me out right now. And the man who is bringing it to me? Lt. Comm. Edward Steichen.

I mean, I kind of stumbled onto the photomural trail last October, when a vintage exhibition print of Mies’ Barcelona Pavilion came up at auction. Its size, scale, and iconic modernist subject suddenly made the photomural seem like a missing link in the contemporary development of both photography and painting. And yet it’s also seeming like not many of these pictures survived, because they were merely exhibition collateral, functional propaganda material, no more an artwork than the brochure or the press release.

And yet these things existed. Is it possible at all that any of these prints still exist in some art handler’s garage?

Anyway, it’ll take me time to process this Road To Victory show, so I’m just going to skip across the most stunning parts: the show’s awesome, explicit propagandistic objectives; the utterly fresh painterly abstraction of these giant prints; the spatial, experiential design of Herber Bayer’s installation; the texts surrounding the exhibit, which traveled around the country in 1942 to apparently wild, patriotic acclaim; and the ironic, complicating aspects of authorship of the show and the work in it.

[Hint: they barely identify, much less mention the actual photographers at all. I, meanwhile, am happy and grateful to credit PhotoEphemera for these small versions of much larger scans of MoMA’s 1942 documentation of the show. Definitely worth diving into.]

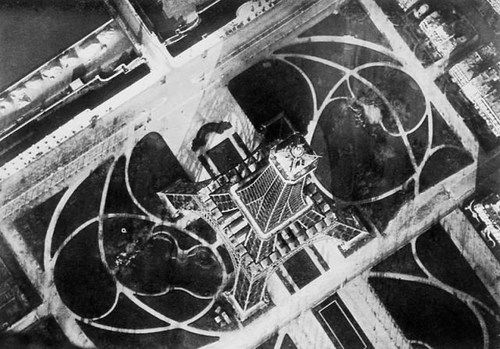

La Tour Eiffel Vu En Ballon

In 1909, balloonist/photographers André Schelcher and Albert Omer-Décugis took this picture from about 50m above the top of the Eiffel Tower. It is one of 40 images they published that year in a book titled, Paris vu en ballon et ses environs.

I just found it in my new Leon Gimpel catalogue, but it turns out to be included in Thierry Gervais’ 2001 article on the beginnings of aerial photography, which I posted about before.

With that angle, I would’ve said Schelcher’s photo looks more Bing than Google Maps, but Google’s got it.

Previously: Le début du point de vue Google Mappienne

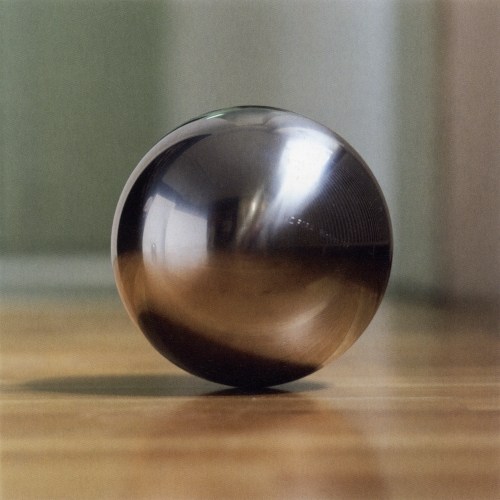

Shiny Balls, By Gerhard Richter

Oh no! I mean, oh yeah!

Gerhard Richter did do other steel balls. At the end of his 1973 interview with Irmeline Lebeer, he complains about my favorites of his series, the grey monochromes:

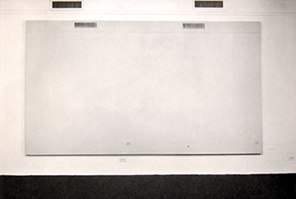

the only problem with them is that they are so beautiful.

And that bothers you?

No, but it’s like a blank canvas. A blank canvas is the most beautiful thing, and yet you can’t just leave it like that. You have to add other elements to it. If it were only a question of perfection, we wouldn’t do anything any more.

You need dynamics and a certain tension.

Without those, everything would be dead. We would all come to an agreement, once and for all, on the sphere. At home, I have these particularly beautiful steel balls.4 But it’s impossible to get any closer to perfection. But we start down that path, it’s all over.

Which is an odd place to put a footnote saying that “Indeed in 1989 and 1992 Richter produced three editions of balls made of gleaming stainless steel.”

The largest was the last, Sphere III [above, via g-r], which was done in an edition of 11. In addition to the title, signature, number and date, each ball is engraved with the name of a Swiss mountain.

Spheres I and II are 8cm [ed. 25] and 5cm [ed. 11], respectively, with no mountains involved. According to the Dallas Museum of Art, which has all of Richter’s balls, they were all published by Anthony d’Offay and fabricated by FAG Kugelfischer, which I will assume is a company. Indeed, under the Schaeffler Group’s guidance, FAG has been a leading German manufacturer of ball bearings for over 120 years.

search results: kugel [gerhard-richter.com]

Previously: Richter’s Balls, Regrets

Art Poster

Honestly, I don’t know why I didn’t see it before. The answer‘s staring me right in the face. And I was so close with the Serra, too.

Annunciation After Titian, 343-1, 1973, Gerhard Richter [image via g-r]

This morning I just cracked open my Richter Bible, and started reading a 1974 interview of the bemused Richter by an insistent Gislind Nabakowski, who pressed the artist for his reasons for implicating himself in the “hackneyed language of symbols” of “the power of the hypocritical Renaissance,” and “sexual domination,” of the painting he’d recently copied, Titian’s Annunciation:

With regard to your approach to painting, you seem willing to encumber yourself with the concept of traditional symbolism, but you don’t illustrate it; you seem to be searching for your own symbolic references. Can you elaborate on this ‘illustrative realism’? Does it represent what the painter sees, or does it reveal his ‘reflections on what he has seen’ i.e., are his paintings platforms for the production of reality?

It certainly doesn’t show what one sees, because everyone sees something different, and what one sees isn’t a painting; it can only remind us of a painting. But, on the other hand, I don’t accept the principal difference between ‘pure’ pictures that only represent themselves and others that just illustrate something. If you take Ryman, Palermo or Marden, for example, in a away their paintings are also illusionistic, and you can only just identify the actual paint or the material if you have the eyes of a paint salesman.

Why did you paint over Titian’s motif and dissolve it?

Oh, I’m sure I didn’t initially plan it that way; I wanted to trace him as precisely as possible, maybe because I wanted to own such a beautiful Titian… [laughs].

That can’t be true. Not even the very first painting is a copy; you intended something else.

Sure. I only copied it from a postcard and not from the original as such. Although I must say that it is indeed possible to reproduce a painting from a postcard that is almost as beautiful as the original. Those few little details that would have been different really don’t matter–but that’s another issue.

Maybe for Richter.

Because when it comes to posters, what do people want to see more than beautiful works of art? The art poster has developed into a genre all its own. A genre and, as every museum shop, dorm quad, and Upper West Side laundry room can attest, a market.

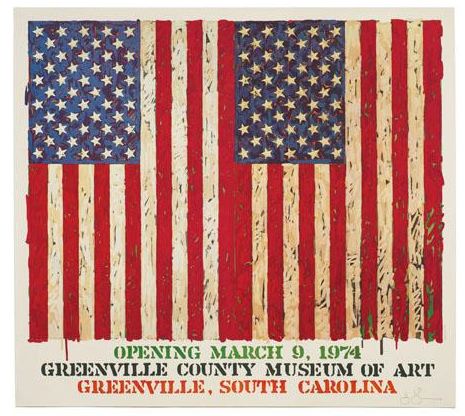

Here is a poster I saw yesterday, Lot 270: Jasper Johns Flag I, which LA Modern is auctioning next month, with a description, “Poster based on the print,” a signature [!], a provenance, and an estimate of $1000-1500:

We demand a lot from our art posters. Posters signal our tastes and aesthetic identifications even more purely than the originals, which, by their scarcity, can only be possessed by a few, and thus can’t escape the aura of investment. Posters can also embody a history. You were there in Greenville in 1974, and Jasper signed your poster. That’s how it could look, anyway. We like our posters to faithfully approximate the experience and presence of the original.

And they must also have a significant, authentic presence–poster qua poster–of their own. Which can limit the works available to those that best fit the poster format. So you can blow up Matisse Jazz cutouts, or shrink a Rothko.

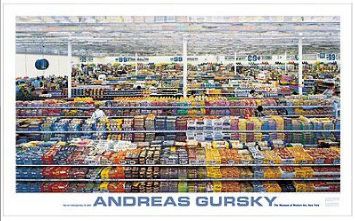

Gursky: 99 Cent, $24.95 [via momastore.org]

Like this powerful work,” Gursky: 99 Cent, a “MoMA Favorite” which pushes up against the dimensional limits of the poster medium [56″ x 34″] just as Gursky’s 207x337cm original tested the most advanced photo printing technology of its day [1999].

But that, as Richter says, is another issue. Just as you can paint a beautiful painting from a postcard, you could use a photo, tiled and transferred to silkscreens at life-size, then taped and folded into a box, to provide the authentic, transformative experience of being in the presence of the original. Assuming you open the box, that is. And that you have enough wallspace. Or maybe that’s what museums and exhibition copies are for. And your copy stays MIB.

So what’d work at that scale? Gursky, of course. But if you’re gonna do Gursky, do the 99 Cent II Diptychon, which unfurls to a positively Bus-like 207 x 682 cm:

99 Cent II Diptychon, 2001, at Philips de Pury in 2006 [image via thecityreview]

Or:

On Frieze At 20

Frieze has been around 20 years? That’s crazy. I feel so old.

I’m really liking the dips into the archives by invited Big Thinkers. Jens Hoffmann’s picks focus on biennials and such. My favorite has to be Jenny Liu’s firsthand report of the Sixth Caribbean Biennial, a giant critique-in-a-boondoggle-in-a-biennial organized by Maurizio Catteland–and Jens Hoffmann:

The idea of a biennial without art could have been cool in a marvellously vacuous sort of a way, puncturing the self-importance of the art world by grotesquely aping it. What we got was a furtive and ungenerous gesture, a covert V-sign flipped at the art world behind its back, when more balls could have made it a divinely impudent mooning in its face. As a critique, the Caribbean Biennial was neutered when the organisers and some of the artists felt the need to prescribe the biennial’s public perception and hide the vacation at its heart. The art was so profoundly and deafeningly absent that some artists took to thinking of themselves as both art stars (whose reputations needed protecting) and art civilians (with commensurate expectations of privacy), while curators took on the role of embarrassed publicists and the spectators of poor cousins at a wedding. There’s something sad about so cynical and ambivalent a gesture as the Caribbean Biennial: one would think that a critique of one’s own practices would be ethical, even idealistic. Here, the humour was both a performance of aggression and a weapon of despair, another cheerless rehearsal of irony and parody.

I still talk to people about the Caribbean Biennial all the time, though as time passes, I have to keep reassuring myself that it actually happened. Or didn’t, as the case may be.

But I still remember it as a sly, subversive prank, and Liu’s obviously generous but disappointed review reminds me that it was less romantic than I want it to be. Seriously, guys, how could you let Jenny down like that?

Trouble in Paradise [frieze]

frieze.com/20/ [frieze.com]

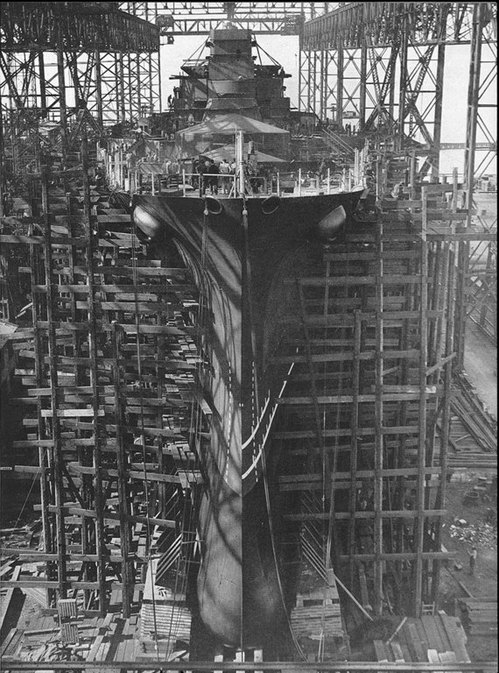

What Other Photo Of A Giant Thing Would You Turn Into A Life-Sized Silkscreen Poster?

It’s true, I like Mason Williams’ 1967 Bus for what it is.

It’s true, I like Mason Williams’ 1967 Bus for what it is.

But right now I love it for how it was made, the whole ridiculous, unanticipated, dogged, improvised, and ultimately successful process: the 4×5 negative; the 16×20 print; the 16-tile silkscreened billboard; the one-ton palletful of paper on the driveway; the cases of Scotch tape on the borrowed dance hall floor, the giant folding by hand; the warning not to open the box in the wind; the realization that after all that, most people are never gonna open the box in the first place.

That last point should negate the question I’ve been pondering, then, which is, if you were to make a giant photomural poster this way today, what image would you use? Assuming–or asserting–that it mattered, and that even though you’re doing it for the process, you’re not just going to use random image noise. [Though that is one option.]

Anyway, a bus is obviously out; you might as well do a reissue of Williams’ original. And though a whole host of large vehicles would be interesting–a dump truck, a train, a plane, perhaps a collector’s G5 as a commission–it might also be a little derivative.

Mondo-Blogo suggested “the ‘dirtbergs’ all over the city now. Facinating how the snow gets so black, and so filled with the most disgusting things.” And I do like their scale, ephemerality and banality, and the combination of abstraction and landscape.

You can’t go too architectural without treading on William Anastasi’s toes, or without aping Urs Fischer’s totalizing wallpaper. But an interesting structure or storefront does have its appeal, even though the idea is a print that feels more like a picture of something, and not an environment or space. It’s objectification through photography, and in turn, turning that photo into an [ultimately, probably] unseen object in a box.

You can’t go too architectural without treading on William Anastasi’s toes, or without aping Urs Fischer’s totalizing wallpaper. But an interesting structure or storefront does have its appeal, even though the idea is a print that feels more like a picture of something, and not an environment or space. It’s objectification through photography, and in turn, turning that photo into an [ultimately, probably] unseen object in a box.

Cheyney Thompson’s epic lifesize painting makes me want to do a newsstand, though.

And since these are objects, why not a large sculpture? Like the gilded Gen. Grant at Grand Army Plaza? Or Simone Bolivar on Sixth Avenue, for that matter? Why not a Torqued Ellipse? Imagine all the ink that silkscreen’d take.

Or maybe a rock or a tree.

What am I not thinking of? I’d be interested to know. What would you like to see? If I make one of them, I’ll be glad to send you a copy. Though if involves a shipping pallet, I may ask for your FedEx account number first.

Warhol Invented Twitter?

My Twitter feed is so complicated right now.

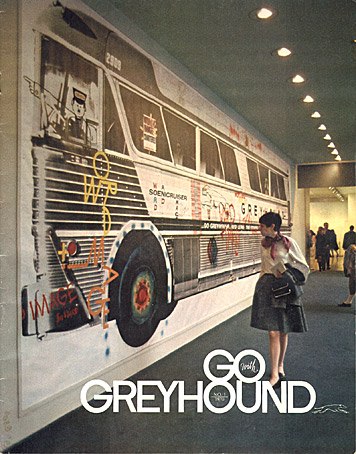

Bus, 1967, Mason WIlliams

A 1968 NY Times review of Robert Rauschenberg’s giant Autobiography edition by Hilton Kramer was titled “Art: Over 53 Feet of Wall Decoration.” And the abstract mentioned simultaneous installations at the Whitney and MoMA, so I was interested to see what else Kramer hated. Turns out it wasn’t a Rauschenberg or a Broadside Art project at all: it was Mason Williams’ Bus.

Mason Williams’ Bus is one of the most awesome photomural/artist book/oddball objects of the Los Angeles 1960s. I love it. It is a life-size photo of a Greyhound bus, folded up and put into a box. It was made in an edition of 200, but existed primarily as a joke, or a poster, or a decoration, and only rarely has it been perceived as an art object.

Which is hilarious–and hilariously wrong–because Williams is a childhood friend and longtime collaborator/co-conspirator with Ed Ruscha, whose deadpan artist books were busy not being recognized as art–or as proper books–at the same time.

This lack of critical appreciation may have something to do with Williams’ primary occupation, which was TV writing and composition; he was the head writer for The Smothers Brothers and wrote “Classical Gas.” Bus was an irreverent stunt, though he took it very seriously.

[For a rare, serious look at Bus, there’s no place better than Design Observer, where Lorraine Wild wrote about it in 2008; Michael Asher had donated his copy of Bus to MOCA, and the museum had just installed it. Wild has Williams’ making of story, the hilarity of which is only hinted at in the parodic text Williams included with each numbered edition:

Actual size photograph of an Actual bus.

10 ft. 3 1/2 in. x 36 ft. 2 in.)

Weighs 10 pounds, 7 ounces.

Conceived by Mason Williams.

Photograph by Max Yavno.

Enlargement made from a 16×20 print of a 4×5 negative. Printed on billboard stock in 16 sections by silk screen process. Printed by The Benline Process Color Company of Deland, Florida and Pacific Display of Los Angeles, Califfornia. [sic] Hand collated, rolled and transported early in the morning by three people (two men and one woman) in one car over a period of several days. Each copy individually hand assembled by three people, using hands, feet, tape sissors [sic] and a Barlow knife. Assembled with 120 ft. (per copy) of Scotch Brand double-faced tape (No. 666).

Folded by hand and foot by three people.

Assembled and folded quietly on television sound stages on Saturday mornings in Los Angeles, Califfornia [sic]. Assembly time, nine man hours per copy.

Cover concept by Bob Willis. Designed from a box found under his bed by his wife. Cover constructed of corrugated fiberboard, 200 lb. test, #1 white. Printed and fabricated by Nehms Company of Los Angeles, California.

Published on the 24th of February, 1967 in a limited edition of 200 copies.

Love that so much, I want to start silkscreening and double-taping life-size photos of things.

Anyway, MoMA installed a copy of Bus in the lobby in Jan. 1968, and then invited graphic designers participating in the Museum’s upcoming poster show to tag the bus with graffiti. Here’s a photo of the result, as seen on the cover of Go Greyhound magazine.

100%, Lorraine Wild [designobserver]

Art Projects by Mason Williams [masonwilliams-online]

Awesome LIFE Magazine photo of Bus at Reference Library

Recognition Models

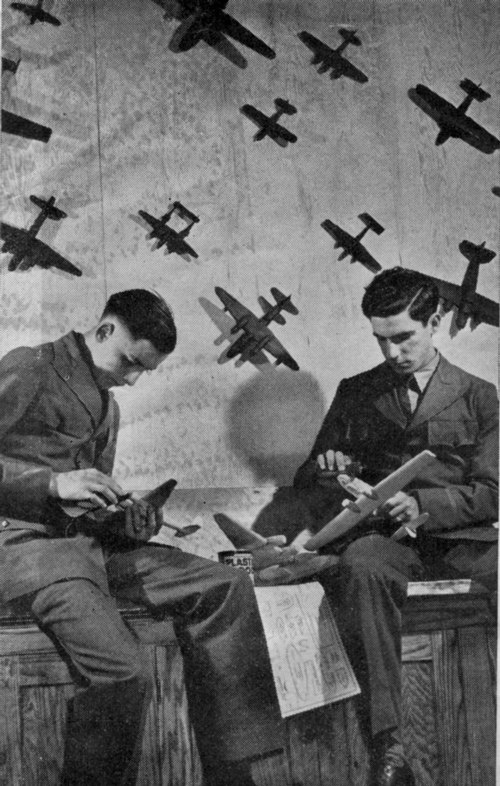

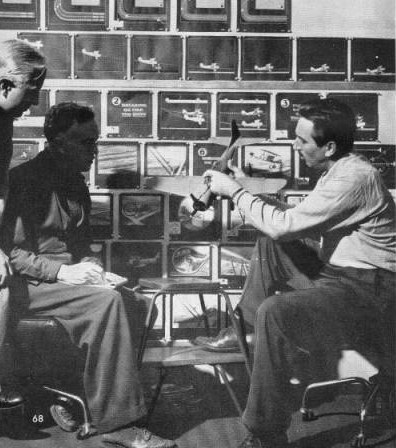

Air Training Corps cadets building recognition models, via CollectAir

Looking for the “Plaster of Paris Aircraft Corp.” and coming up empty [stay tuned], I did find plenty of aircraft made from Plaster of Paris: WWII-era recognition models used to train military personnel and civilian planespotters to distinguish between friendly and enemy aircraft. Though recognition models and plane silhouette posters and such were used as early as planes themselves, planespotting efforts surged during World War II.

Models were needed to train millions of soldiers, for whom distinguishing planes was a matter of survival and victory on the battlefield, and to train millions of volunteers in the Ground Observer Corps, who were manning towers and outposts all along America’s coasts. [British planespotters actually ended up having much more to do.]

Official StromBecKer model kit of the Boeing Flying Fortress, via CollectAir

To source all these models, manufacturers developed injection-molded cellulose plastic technologies to crank them out, and schoolchildren were enlisted to build them from kits of wood, or to carve them to spec from other non-strategic materials. Like Plaster of Paris.

Like the Civilian Camouflage Council mobilized by New York artists and art directors in 1942, and these insane canvas-and-stilts bomber trainers, these recognition models are an awesome melding of militarism and craft, cutting edge technology and ad hoc bricolage.

Walt Disney with reconition models, and the diagram for a Naval flight training film on the wall, from LIFE, via Collectair

They’re interesting and novel to me, but also esoteric and esthetic. For the folks who grew up during the war, they were life and death, vital, formative to their world.

And they’re apparently being forgotten. The images here [and the information, basically everything I know about recognition models that didn’t come from the opening of Empire of the Sun] come from Steve Remington’s CollectAir Friend or Foe? Museum, an extraordinary collection of recognition models and related training material located in Santa Barbara. There’s much, much more on the website, including the planespotting training kites, gorgeous shipspotting models, including one British Razzle Dazzle model, on and on.

Friend or Foe? Museum [collectair.com]

Provenance

Wow, so I’m just throwing Jasper Johns’ name into the archives of New York Magazine, and up pops this wild story from 1982 about Frank Waxman, a Philadelphia doctor who amassed a blue chip collection of tiny artworks by stealing them from galleries.

Wow, so I’m just throwing Jasper Johns’ name into the archives of New York Magazine, and up pops this wild story from 1982 about Frank Waxman, a Philadelphia doctor who amassed a blue chip collection of tiny artworks by stealing them from galleries.

He was on the Friends of the Philadelphia Museum committee, hosted collection visits, and basically stole 170 artworks in four cities before he was caught.

Waxman got a Johns Flashlight sculpture from Irving Blum’s desk in SoHo; a couple of Joseph Cornell boxes; an Agnes Martin from Robert Elkon Gallery; here’s Herbert Palmer’s 2004 account of having a Picasso bronze stolen from his Los Angeles gallery:

MR. PALMER: And one Christmas, I left a few days early to go skiing. And I get a phone call from the young lady who was working here then; she said, Mr. Palmer, did you put the Picasso away for safekeeping? I said, I don’t think so. She says, well, it isn’t there.

DR. EHRLICH: [Laughs] Oops.

MR. PALMER: I said, do you think someone might have taken it? She says, no the case is screwed down. I [She] went back there and after 10 minutes on the telephone, she comes back; the screws are not in the case. She says, I know who took it. I said, do you know his name? She said, no. The man with the trench coat, he came in twice. Once he came in, and he looked around. The second time he came in, he asked me to show him a picture, and I had to go to the back of the gallery to get the picture.

DR. EHRLICH: Oh.

MR. PALMER: And at that time, he took the Picasso and slipped it into his coat, which was designed specifically for stealing small sculpture. It had big pockets.

DR. EHRLICH: Wow.

MR. PALMER: Big, padded pockets. She says, he took it. I said, you have no clue as to his name or anything? No. I said, call the insurance company, call the police, and don’t you leave – Christmas Eve – don’t you leave until the police come. They came and they wrote it up – you know, the paperwork.

While they’re writing up my case, the police get a phone call. A woman is screaming. He took my Rodin, she said; some crazy woman is yelling, hey, somebody took her Rodin. I said, I know who it is. If you’re quick, you can catch him. It was Feingarten, Mrs. Feingarten. She had a gallery on Melrose, and this guy – same guy who stole from me, went down there and did the same thing – sent her to the back; while she was in the back, he took this Rodin hand she had, and put it in his coat, and walked out with – and she saw him do it. And she screamed at him, put that down. He said, don’t come close – threatened her, so she didn’t; she called the police.

And she said, wait a minute – I have a clue. He left a phone number, because it was Saturday, and I had to open the gallery for him out of hours.

Cops finally cracked the caper, Waxman was eventually arrested, got the psychiatric help he needed, all the artwork was returned, and now people get to tell fun stories about how their stolen Picasso was on the cover of New York magazine. It’s win-win. The only loser here–since Waxman didn’t get started until the late 1970s, and was thus too young to have been involved in the Johns Flag caper–is me.

Oral history interview with Herbert Palmer, 2004 Dec. 6-22 [aaa.si.edu]

Flags And Flags And Flags

Andy sent along this great ffffffound fffffflag picture, posted today on thekingof.tumblr.

which reminds me of one of my favorite Johns riffs, the 2005 work by Jonathan Horowitz, Three Rainbow American Flags for Jasper in the Style of the Artist’s Boyfriend: