That Google Street View snafu yesterday reminded me of a still from Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s 1932 abstract//constructivist short film, Lichtspiel, or Lightplay.

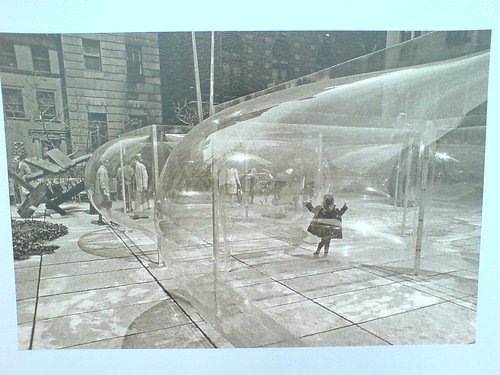

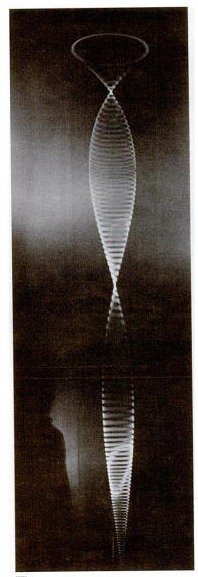

Normally, I’d say that’s the art-nerdiest possible free association in the world, but I’ve actually been meaning to write about Moholy-Nagy’s film for a while. Or more specifically, about his incredible kinetic assemblage/sculpture used to make Lichtspiel, the Light Space Modulator.

Light Space Modulator is a motorized sculpture made of glass, mirror, steel, and acrylic, and it was a crucial object–or project–for Moholy-Nagy for more than two decades. The dates generally given for its construction are 1922-30, but the artist worked on or with it until he died in 1946. Last fall, Alice Rawsthorn wrote in the Times about the tragicomic scene of the refugee artist fleeing the Nazis in the 1930s, family and Light Space Modulator in tow, and having to explain the sculpture to customs and border officials along the way. The original was given by Moholy-Nagy’s widow to the Harvard Museums, but more on that later.

According to the artist’s official chronology, Lichtspiel [full title: Lichtspiel schwarz weiss grau] was made around 1930 in Berlin, and first shown in 1932 [MoMA has a brochure, designed by the artist, for an exhibition and screening.]

According to MKZ:

Lichtspiel, schwarz-weiß-grau was originally supposed to consist of six parts, but only the last part was filmed. The first five parts were supposed to show different forms of light in set combinations: from the self-lighting match, automobile headlights, reflections, moonlight, and colored projections with prisms and mirrors to the production of the “light prop,” [i.e., the LSM]

This surviving segment/film, one of 7 extant Moholy-Nagy films, is listed with a 6-minute run time, but there are several excerpts and variations floating around. Here’s the original, I think:

The Times has a great account from 1952 of a screening of an “abstract art film” program organized by “Captain [Edward] Steichen” for the Museum of Modern Art’s “enterprising, energetic Junior Council,” which included both Lichtspiel and the early direct animation films of Len Lye.

But SFMoMA’s version is 5:17. The Minimalist Issue of Aspen Magazine, Nos. 5+6, published in 1967, includes a 1:40 excerpt on super-8 film. Fortunately for everyone without Aspen and/or an 8mm film projector, there’s Ubu.