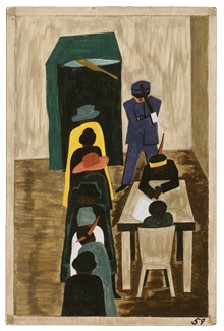

Last week, I took my 4-yo daughter to the Phillips Collection to see Jacob Lawrence’s masterpiece, The Migration of the Negro. It turned out to be the last day of the exhibition where the entire 60-panel series was on view. [MoMA owns the even-numbered paintings, the Phillips owns the odd-numbered ones.]

We’ve grown familiar seeing it all together this summer, but in the crowded gallery, as I read the caption on each panel and held the kid up so she could see, I couldn’t help but choke up when I got to the end, the culmination of The Great Migration, where millions of citizens fled the vestiges of the Civil War–poverty, discrimination, injustice, and violence–for an opportunity to work, go to school, raise their families–and to vote.

Category: art

Finding Double Negative has never been easier

Not since we programmed it into the navigation system of my in-laws’ car, anyway.

The car also has an offroad navigation feature that logs virtual GPS breadcrumbs at preset intervals along the way, but it proved unnecessary. The nearly featureless mesa where Heizer’s land artwork is sited turns out to be a road with a name: Carp Elgin Rd.

In fact, there it is on Google Maps, one of the tightest satellite shots I’ve ever seen of Double Negative. Crazy.

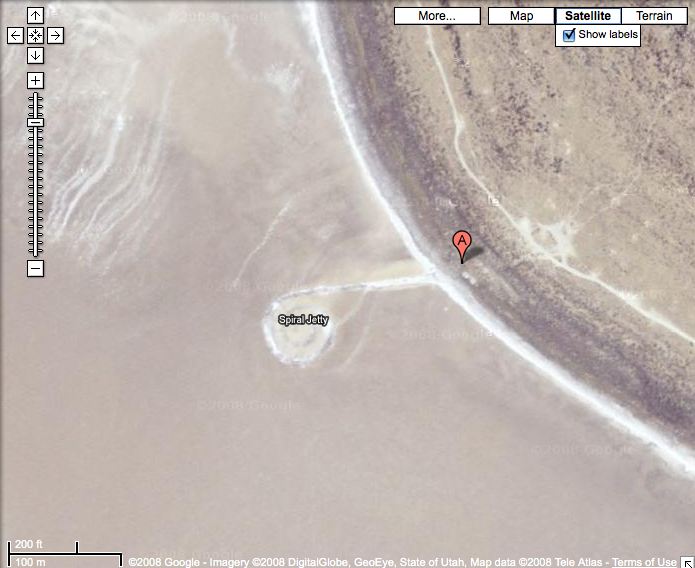

Update: OK, not to get all George Bush and the Grocery Scanner about it, but I just typed “Spiral Jetty” into Google Maps, and it came right up. With an upgraded photograph–and a label.

In fact, here are complete driving directions to the Jetty from 213 Park Avenue South, the former location of Max’s Kansas City. [note: there is a weird little, unnecessary jog at the very end that I couldn’t fix, but I’m not worried. Given the rate at which technology is iterating and altering the way once-isolated land artworks are experienced and perceived, I expect a realtime Google Streetview of the Jetty is already being planned on a whiteboard somewhere in Mountain View.]

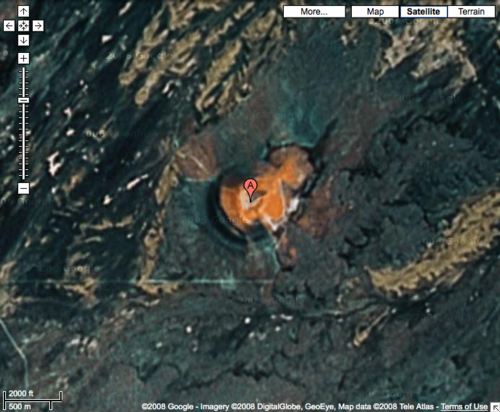

Clearly, Google has been augmenting its map search with information found on the rest of the web. An otherwise seemingly Googleproof project like Michael Heizer’s City, which he sited as remotely as he could, is pinpointed by latitude and longitude coordinates published on a Land Art site. City also has newer photos.

Roden Crater’s there, under “Roden Crater, AZ,” but it still has the quaint, old-timey satellite photo from 2005 or whatever. I hope they’ll get around to upgrading it by the time Turrell finishes.

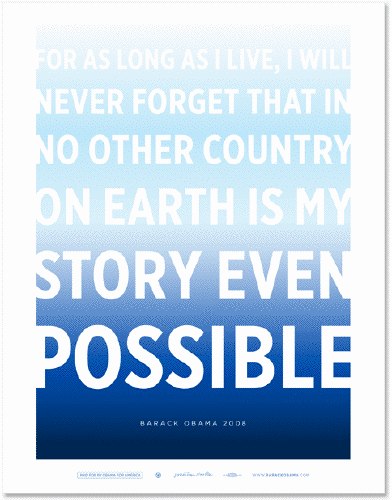

“Possible” By Jonathan Hoefler For Artists For Obama

“For as long as I live, I will never forget that in no other country on earth is my story even possible.”

I just bought Jonathan Hoefler’s poster from the Barack Obama store. If you hurry, 4799 more of you can do the same.

“Possible” by type designer Jonathan Hoefler, $60 donation [store.barackobama.com via daringfireball]

Walter De Maria’s Las Vegas Piece

Here’s Walter De Maria describing his early land art work, Las Vegas Piece, to Paul Cummings in 1972. According to the Center For Land Use Interpretation, the piece is off Carp/Elgin Road in the Tula Desert, one exit north of Double Negative‘s Overton exit on I-15. The work is now “apparently” lost:

it takes you about 2 or 3 hours to drive out to the valley and there is nothing in this valley except a cattle corral somewhere in the back of the valley. Then it takes you 20 minutes to walk off the road to get to the sculpture, so some people have missed it, have lost it. Then, when you hit this sculpture which is a mile long line cut with a bulldozer, at that point you have a choice of walking either east or west. If you walk east you hit a dead end; if you walk west you hit another road, at another point, you hit another line and you actually have a choice. At that point you decide which way to go and so forth, then you continue, you walk another mile and at another point you walk another half mile so and at a certain point you have to double back. After spending about four hours, you have walked through all of the three miles of the thing and you would have gotten your orientation because the sun will also be setting in the west and this is lined up so that all the lines are either east-west or north-south. Now I did this piece in 1969 and I haven’t done an article on it because I didn’t find a way to photograph it properly. You can only photograph in multiple views, you know, like this is looking east and this is looking . . . .

PC: A satellite shot.

WDM: Well, that’s true, but that’s a different experience because that’s an experience like a drawing but this is an experience at ground level, it’s a different experience.

PC: How wide are the lines?

WDM: Ten feet wide, eight or ten feet wide.

PC: And they are how deep?

WDM: Oh, it’s about a foot deep, two feet deep and about eight feet wide. The point I’m making here is that the most beautiful thing is to experience a work of art over a period of time. For instance, architecture we know has always thought about this. You go into the palace, you go into the house, you experience the different floors, you sit in certain rooms for certain amounts of time and when, after an hour or half hour or four or five hours you walk out again. You’ve experienced all of the proportion and relationships; you’ve experienced something over a period of time. Well, most sculptures have always been confined to being a single object, no mater what the style of configuration — expressionist or figurative, whatever.

PC: You look at it from this point and that point.

WDM: You look at it and maybe walk around it and, basically, let’s face it. How much time does a person spend with a piece of sculpture? An average of perhaps less than one minute, maximum of five or ten, tops. Nobody spends ten minutes looking at one piece of sculpture. So by starting to work with land sculpture in 1968 I was able to make things of scale completely unknown to this time, and able to occupy people with a single work for periods of up to an entire day. A period could even be longer but in this case if it takes you two hours to go out to the piece and if you take four hours to see the piece and it takes you two hours to go back, you have to spend eight hours with this piece, at least four hours with it immediately, although to some extent the entrance and the exit is part of the experience of the piece. So what happened, though, which was very interesting in connection with the idea of theatre or film is that to build one of these pieces becomes a major logistical economic undertaking. Like if a person wants to make a movie, we all now that it takes sixty or eighty thousand dollars to make a feature film of any kind, black and white, not too much original music and not too many name stars, and it takes four or five hundred thousand dollars to make any medium size picture and a million to two million dollars to make any decent type of major film. Well, the notion that maybe a piece of sculpture might take an investment of forty or fifty thousand dollars and . . . but when it’s finished, it gives the person an experience with could take him several ours or several days to experience is something I’ve been fighting now for the last four years, starting now the fifth year.

The comparisons to architecture and cinema are both eye-opening. Minimalists like Judd and Flavin spoke of sculpture as space, but De Maria’s talking about sculpture as time. Which is worth remembering when you sign up for a 24-hour stay at the Lightning Field.

Backroads Backstory: Walter De Maria On Michael Heizer

I started poking around a bit on the making of story of Michael Heizer’s Double Negative. I’d known that it was commissioned by Virginia Dwan, the incredible gallerist who was also behind Smithson’s Spiral Jetty. Here’s a bit of her story from Michael Kimmelman’s 2003 visit with her:

She contracted him to do a work. He disappeared. Months later it was done. ”Double Negative” is a 1,500-foot-long, 50-foot-deep, 30-foot-wide gash cut into facing slopes of an obscure mesa in Nevada, a project that required blasting 240,000 tons of rock. ”It cost under $30,000,” Ms. Dwan says, ”pocket change for art today. I saw it only after it was finished. That’s how I operated. If I believed in the artist I trusted him.”

Then I came across an interesting 1972 Smithsonian interview Paul Cummings with Heizer’s earthwork colleague, Walter De Maria, two artists who romanced the desert together. I love the unselfconscious references to Kerouacking and creating an art movement. No way you could pull that off today:

WDM: Well, I drove across the country with Mike Heiser who I had been spending a lot of time with in ’67. So we had this chance to have the great American Kerouac experience of driving, you know, drive, drive and it never stops and four or five days later you can make it if you drive night and day. When I had first driven the country in the summer of ’63 from New York back to California, it was the most terrific experience of my life, experiencing the great plains and the Rockies, but especially the desert, you know. No, I would say the drive through Nevada in ’63 was the first time I was in the desert. And that memory was to come back in the crisis. Where is the best place in the world? It’s what I saw in Nevada. So it was a chance to go back to the desert for a second time and this time to start going out there often. We met flyers and we learned what it was like to fly small planes and drive trucks on these dry lakes and stuff.

…

We had a lot in common; we knew the whole situation so that gave us something to talk about and from that point it became interesting that he would change from shaped canvas painting to sculpture, and I was at the point of changing from steel sculpture into the land sculpture. So it was a move that we both wanted to make at the same time. We have both been developing the land sculpture simultaneously since that time, five years ago, just about until today. We’re really starting the sixth year. I mean, you know, we did it. It’s something that two people could do that one couldn’t, really, create a movement, because if one person does it, it is almost an eccentricity, but if two people are doing it and then they influence two others or three. It takes no more than three or four or five people to make a movement and then those people of course can have a hundred or two hundred or five hundred or a thousand following them. But the key idea is to develop two or three people. But it’s not necessary, sometimes three or four or five people could be working simultaneously. Like this guy Richard Long was working in England, walking around in the fields in ’68 also. That was completely independent simultaneous development…

The mention of flyers and deserts reminds me of Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point, which I’ve been watching lately. James Turrell is another flyer–and land art biggie, what with the Roden Crater and all. Don’t think I’ve heard much mention of that. Of course, there was Smithson and The Plane, but that wouldn’t be till ’73. Anyway, here’s more De Maria on one paradox of land art:

We’ve fought a lot of the same people; we’ve shared some of the same patrons, the same gallery like Dwan, Frederich for a while in Germany. Now he has another gallery. And all of our same problems remain, like to make earth art exist in the face of a lot of the same structural problems that still exist. Galleries are not set up to back major sculptures.

PC: Right.

WDM: There’s nothing set up to sell major sculptures. Museums do not commission major sculptures, even though they go off and spend five million dollars on an old painting. And not only that, a lot of people don’t believe that it really exists. There is still a lot of misconception that it exists only for the photograph and not for itself. It’s so far away that maybe everyone in the art world knows about our sculpture but not even one thousandth of one percent of a person has ever seen one of the pieces with is a very interesting conceptual and visible aspect of something that is massive. So, with all of these confusions and contradictions still inherent in the work, one could see another five years of good problems and hopefully some good solutions coming up. [emphasis added]

And it turns out that De Maria created his own trench-in-the-desert land art in 1969, Las Vegas Piece, which is just up the road from Double Negative. Or should I say “road.” CLUI says it’s located on Carp/Elgin Road, which, according to my father-in-law’s GPS navigation, is the same dirt road that passes alongside Double Negative.

De Maria talked about Las Vegas Piece in the Smithsonian interview. But when he reports Dwan’s account of visiting it, it is Kimmelman who waxes a little romantic:

It consisted of dirt paths he cut into the Nevada desert, going nowhere. In my mind — maybe Walter would say this is untrue — the desert setting, the heat and sun and emptiness were so important to the work because you were made to feel absolutely alone. First, it was a safari to find it, and when you did, you were separated from everyone else if you wandered down the paths, because the land was uneven, although it looked flat from far away, so you would find yourself on the far side of a rise, alone in the desert.

”I love the sense of isolation and solitude. But at the same time Walter’s art almost pushes a spectator away, as if he’s saying, ‘Stay back.’ ”

And so it goes that the foreboding environment of the desert itself moves to the foreground of the land art experience. It’s part of the mythology and story of the piece, told and retold without firsthand confirmation by the 99.999% of art world citizens who don’t actually go. Like this NY Times travel article starring Dave Hickey and his wife as daring land art tour guides:

Mr. Hickey’s wife, the curator Libby Lumpkin, had suggested that Chris and I drive into the desert to see Michael Heizer’s earth art piece from 1969-70, “Double Negative” (doublenegative.tarasen.net). A work I was curious to see, it was famously hard to find. She had us meet her at the Las Vegas Art Museum, where she is the consulting executive director, to get directions.

…

She warned us to take plenty of water. People had died, she claimed, after losing their way on Mormon Mesa, where “Double Negative” is carved. The Internet directions she’d handed us turned out to be more precise on paper than in the featureless landscape. After driving an hour and a half northeast to Overton, we followed a dirt road up the side of the mesa.

Rocks on top threatened to puncture the oil pan on the Neon, so I parked. We stumbled around, visoring our hands against the sun. Nothing in sight looked like art.

We flagged down two cars but no one had ever heard of the work. Discouraged and clueless, we were heading back to the city when we saw an S.U.V. The driver, an elderly man from Overton, had been to “Double Negative.” He pronounced it a “tax dodge,” but agreed to lead us there anyway.

Now I want to go back and see what’s up with De Maria’s Las Vegas Piece, but not only is CLUI’s coordinate map hopelessly vague [“The site is 37 miles down the road, off another small trail.”], not even they can be bothered to confirm its continued existence. All they say about it is, “Apparently, no longer visible.”

Went To See Double Negative Yesterday. Film At 11

So all this time I imagine that Michael Heizer’s Double Negative, dug into the edge of Mormon Mesa, is like the lost earthwork, no one can get to it, no one can find it, &c., &c.

Turns out the thing’s an hour outside Las Vegas, like 15 minutes from cheery downtown Overton, which is an exit on I-15. At least I assume downtown Overton’s cheery; we didn’t actually make it that far. Turned off by the airport, took Mormon Mesa Rd. across, then turned left onto, uh, Double Negative Way, just before the cattle guard.

If Spiral Jetty was this easy to visit, there’d be a day spa there by now. Or at least a Cracker Barrel.

driving directions to get you almost all the way to Double Negative, then you just drive slowly north along the scalloped edge of the mesa, three scallops, and you’re there!

October Surprise

I was talking with an artist friend yesterday, and he made a reference to “Krauss’s ‘Sculpture and the Expanded Field’,” and I was all, “huh?” And he was all, “WHAT?” And so I was like, “Don’t know it,” and he was all, “Dude, it’s canon. First handout they give you when you get into art school.” And I was like, “And who reads October unless they’re being graded on it?”

Still, once he explained her postmodernist proposition for sculpture, I was like, “Expanded Field? We’re soaking in it!”

So I read it, and yeah, I knew that; it’s basically the idea that in the late 1960’s, artists challenged and expanded the definition of sculpture, or to flip it around, the logical structure of artists’ practice expanded beyond the finite, inherited modernist definition of sculpture. There’s even a fancy diagram to explain why what Robert Smithson, Richard Serra, Robert Morris, and others of the era were doing is not modernism, but is sculpture.

Anyway, here’s a PDF version of Rosalind Krauss’s “Sculpture and the Expanded Field”. Get an education so you don’t embarrass yourself like I did. [sic and/or heh]

You Have A Stingel? No Way! I Have A Stingel!

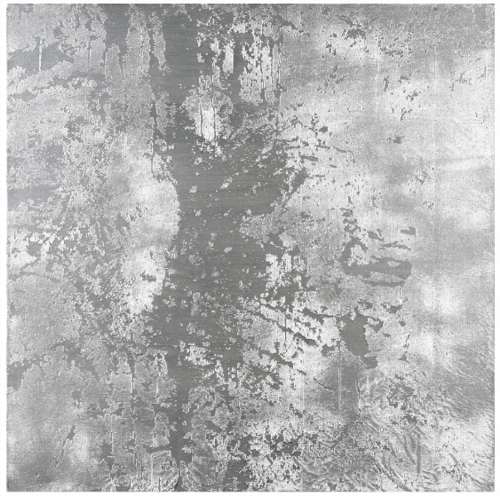

In 1989, artist Rudolf Stingel published Instructions, an illustrated booklet showing how to make one of his silver paintings. “He challenges the process of creating a painting and questions the concept of the canvas and that of authorship,” says Christie’s in a paraphrase of the curator Francesco Bonami. Christie’s is selling a 1998 silver Stingel painting [whatever that means, we’ll get to in a second] in London in a couple of weeks. Christie’s explains how they’re made:

The works begin with the application of a thick layer of paint in a particular colour, in the case of the present example silver enamel, to the canvas. Pieces of gauze are then placed over the surface of the canvas and silver paint is added using a spray gun. Finally, the gauze is removed, resulting in a richly textured surface. When seen in conjunction with the DIY manual, the Warholian nature of Stingel’s work is difficult to refute: technical methods of factory-like production, which are openly communicated and question authorship, contrast the provoked coincidences that result in individual monotypes. Particularly, a parallel to Warhol’s so-called Piss Paintings comes to mind: both artists test the methods of what can be considered painting, while simultaneously emphasising the carnality of the practice by combining coincidence and will in a process solely focused on the canvas’s skin. With Stingel’s works, the aggravation of the derma creates the rapture.

I love it, except that the challenge to authorship is merely a conceptual pose, one refuted most immediately by Stingel’s signature on this painting and its £120,000 – £160,000 sale estimate.

Bonami reads the Instructions as “tricking you into learning how to do a painting for someone else.” Which, though, is the neater trick: following the artist’s instructions and making a Stingel for myself, or getting someone to spend £200,000 on an identical painting from the artist’s factory because it has Stingel’s autograph on the back?

The invocation of Warhol and the Piss Paintings is illuminating, and not just for the works’ focus on a painting’s surface or skin–or derma. Such process-oriented practice, which embraces a degree of randomness, conveniently results in serial works of unfakeable uniqueness. They don’t need stamps of authenticity; the object is its own fingerprint. With minimal documentation at the time of creation in his studio, Stingel’s collectors will never face scandals of authorship like those engulfing the Warhol Estate’s authentication board. According to the board’s self-contradictory interpretations of Warhol’s Factory processes, mass-produced silkscreens that Warhol never saw can be accepted as works, while a documented self-portrait can be rejected repeatedly.

On the flip side, though, if Stingel really wanted to challenge authorship and treat each painting as a “cell” that only gains meaning from its connection to countless others, he’d get more traction by treating the world’s DIY Stingels as intrinsic parts of his own work. Locate, document, and show them in galleries and museum retrospectives. Let them be bought and sold in the secondary [primary?] market. Then when one of those works shows up at Christie’s, we’ll talk again about questioning the concept of authorship.

Lot 319: Rudolf Stingel (b. 1956),

Untitled

signed and dated ‘Stingel 98’ (on the reverse)

oil and enamel on canvas

32 x 32in. (81.3 x 81.3cm.)

Executed in 1998

Estimate: £120,000 – £160,000 [christies.com]

Rudolf Stingel – Selected works [paulacoopergallery.com]

So How’s That Spiral Jetty Doin’?

Is he done? I think so. Tyler Green has turned Modern Art Notes into State of Spiral Jetty Notes this week, and it seems clear to me that the biggest entropic threat Smithson’s masterpiece faces is not natural, but institutional.

Green looks at the mining and commercial interests with development plans for the Great Salt Lake; Utah state government officials who court industry and economic development and who are only beginning to grasp the Jetty’s global significance; local conservation and environmental groups whose shoestring grassroots efforts were the only thing that stopped the oil drilling near the Jetty this past spring; and last and unfortunately least, Dia, the art institution which is steward–and in many cases, commissioner–of many Jetty-vintage earthworks.

I wonder if it means anything that Smithson’s widow and estate representative, Nancy Holt, isn’t really discussed or quoted in the otherwise exhaustive series? Or that there’s no mention of Dia’s total ball-dropping in regard to the state’s apparently unilateral decision in 2006 to “clean up” the shore line near the Jetty, a process which involved removing several dozen truckloads of “junk,” including some industrial ruins that Smithson referenced in his siting of the piece.

Dia’s lack of involvement and strategic vision for the Jetty is complicated at the moment by the institution’s own turmoil and leadership transition, but I can’t help but feel worried even calling Dia an “institution.” Even under Michael Govan’s high profile leadership, Dia has always felt like a virtual organization, an instantiation of the whims of whatever deep-pocketed funder was around at the moment. [Wow, was MIchael Kimmelman’s look at Dia’s manic history really from 2003? It feels much longer ago than that.] The kinds of political and coalition-related imperatives that Tyler discusses–and on which the Jetty’s very survival apparently now hangs–seem completely alien to a bauble like Dia.

MAN Series on Preserving Spiral Jetty [modern art notes]

Previously: Oil drilling was part of the picture when Smithson sited the Jetty

Cleanup crew: 1, Entropy: 0

Related rumination: What if sprawl is the real entropy?

Films, Fax Murals & More: Stan VanDerBeek At Guild & Greyshkul

I first encountered filmmaker Stan VanDerBeek’s work in Aspen Magazine. His 1964 collaboration with Robert Morris, Site, combined dance/performance, art, and film. Performers create a physical, 3-D approximation of camera wipes and reveals using large black and white panels. Though Morris and VanDerBeek made it years before, it reminds me of early video art work from WGBH that explored the functions and visual properties of the new technology.

Throughout his career, VanDerBeek was an “advocate of the application of a utopian fusion of art and technology.” [That’s from his E.A.I bio on Ubu, btw.] Which would be interesting enough on its own. But until I get down there to see the actual show, what I find most fascinating about Guild & Greyshkul’s current survey of VanDerBeek’s varied output is the intricacies of how his family began dealing with it after he passed away.

Two of G&G’s artist-owners are VanDerBeek’s children, and the process they went through–part biographical, part familial, part art historical, part archive/conservational–is just awesome. Sara VanDerBeek’s discussion with Brian Sholis is at Artforum.com.

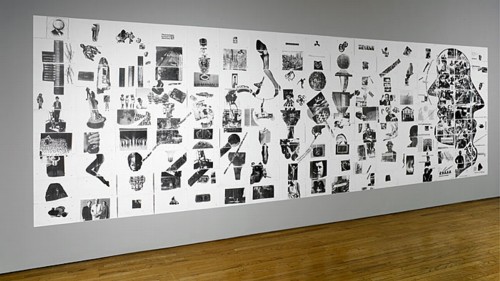

The image above is Panels for the Walls of the World, a 153-panel “fax mural” which VanDerBeek sent from MIT to various places around the country in 1970. Phase I, above, was transmitted to the Walker Art Center. There were four “phases” of Panels, and it’s possible that a significant percentage of all the fax toner in the country in 1970 was exhausted printing out VanDerBeek’s murals.

Stan VanDerBeek runs through Oct. 18 at Guild & Greyshkul; Navigate from this crazy page, too [guildgreyshkul]

500 Words | Stan VanDerBeek by Sara VanDerBeek [artforum]

Films of Stan VanDerBeek [ubu]

Overheard On 24th Street

“Hi, this is Dash.”

Met Throws Lot In With Curator

I really didn’t follow the Metropolitan Museum’s horse race to see who would replace Philippe de Montebello as director, but I find myself caring deeply that it’s tapestry curator Thomas Campbell.

Campbell’s two shows on Renaissance and Baroque tapestries in 2002 and 2007 respectively, were some of the most unexpectedly spectacular and intelligent exhibitions I’ve ever seen. The Renaissance show was quite moving, even, which still surprises me.

So given all the possible museum world follies that could have befallen the selection, it feels very heartening that the museum has chosen someone with curatorial depth and scholarship, who’s able to make highly relevant cases for even seemingly secondary arts, and to put on truly beautiful, important shows.

Well, I Remember The First Time I Visited The Spiral Jetty

Former NGA curator and Dia director Jeffrey Weiss writes about the state of Land Art in the latest issue of Artforum. His focus: T.S.O.Y.W., a 3-hour Earthworks road trip movie/installation by Amy Granat and Drew Heitzler shown in this year’s Whitney Biennial, and the Sculpture Center’s recent exhibition of feminism and Land Art in the 1970’s [which featured the Agnes Denes work, Wheatfield – A Confrontation in Battery Park City that I mentioned a couple of months ago.]

As Earthworks come of age, their fate has begun to look contingent and fragile. Those who are charged with caring for the sites are rightly doing what they can to forestall change; but a true poetics of Land art–given the very nature of the medium–must at least contend with the conflict between an ethic of preservation and the entropic pull of nature and culture that belongs to the content of the work. In this setting, Granat and Heitzler are melancholic visionaries. Their wheels, like reels, turn in order to draw a straight line and follow it: Their line is the road, a figure for unbounded space and inexhaustible time. But as their bike moves forward, their eyes gaze, historically, back; T.S.O.Y.W. shows us that memory has become a chief element of the temporal condition of the Earthwork. The film’s end is a running-down and out, a sudden shift from images of the infinite desert to scarred film leader, then, abruptly, to nothing at all. Forever turns out to be the ultimate conceit. [emphasis added]

Hmm, let’s ignore the conceit of a film ending abruptly while it’s actually screening on an endless loop in a gallery.

I’m intrigued by the idea that memory is a “chief element” of Land Art and its “temporal condition,” if it somehow equates to the divergence between the contemporary condition and experience of visiting the work/site and its various representations, whether in film, photograph, or documenting ephemera.

For most art audience members over the intervening decades–curators, critics, collectors and artists included– Land Art exists as books, photos, gallery presentations, and texts. At the Whitney’s Robert Smithson retrospective in 2005, one symposium panelist went so far as to argue that Spiral Jetty was primarily a film and photo work, as if the jetty itself were just a location, a bit of IMDb trivia. It sounded to me then like just the kind of critical reading that a New York art worlder would make who’d come of age when the Jetty was submerged, and who’d never bothered going to Utah in the 10+ years since it re-appeared.

With images and expectations formed in our head, actually visiting an Earthwork can be as disorienting as meeting your favorite NPR host. Or if, as Weiss points out, the work has deteriorated over time, it’s like meeting an author who hasn’t updated his bookjacket photo for a while. And the disconnect can be jarring; When Titus O’Brien made his pilgrimage to Smithson’s last work, Amarillo Ramp, he found the powerful sculptural form of the iconic 1973 photograph had become “a worn down, weed covered, neglected berm of dirt you’d just mistake for an old watering trough dam. A phantom.”

But memory is more than the gap between reality and what we think reality is; it’s the reconciliation and construction of the two. Weiss’s concerns about the complications Land Art curators face is right, but maybe not in the way he says. From Marfa to the Lightning Field to the Jetty to even Michael Heizer’s Double Negative and Turrell’s Roden Crater, the Earthworks Road Trip has matured in the last decade as both a real experience and a concept. As more people make the pilgrimages and have personal encounters with these works, not only do their memories of the works change, but other people begin to perceive the works not just as images in a book or on a wall, but as visitable sites.

I wonder how the perceptions and understanding of Walter deMaria’s Lightning Field change when they’re based, not just on John Cliett’s dramatic, official photos [via], but on firsthand accounts of the 24-hour visiting experience, very few of which appear to involve actual lightning? And how would that change if Dia and deMaria allowed visitor photographs? When it comes to Land Art in the present and future, there are still a few more conceits left to be addressed.

Don’t Go Chasing ‘Waterfalls’ Before Lunch

The water that falls half as long falls twice as bright.

If the best part of Olafur’s New York City Waterfalls is how their manmade nature is emphasized by their somewhat arbitrary schedule, well, they just got twice as arbitrary, and so twice as good.

The Public Arts Fund has announced a 50% cutback [from 101 hrs/wk to 50] and revised operating hours for the waterfalls after complaints that the salty mist is killing shrubs in Brooklyn.

Beginning Sept. 8th, the new hours are:

5:30 p.m. to 9 p.m. Mondays and Wednesdays

12:30 p.m. to 9 p.m. Tuesdays, Thursdays, Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays.

Please plan your dog walks accordingly.

Hours Are Cut for ‘Waterfalls’ [nyt/ap]

No One Cares About An “Arts Policy” This Year

I’ve had some intense conversations with people who wanted to know what the US presidential candidates thought about the arts, who is advising them, and what their policy statements were on the matter. Frankly, I couldn’t have cared less at the time, and now that I know the answer, I can hardly think of a less significant or important issue on which to base a decision. What the two presidential candidates do and say in other realms–in fact, their entire governing philosophies and the way they would lead the country–will have exponentially greater impact on US’s culture, arts, and artist communities than whatever handful of legislative bullet points they throw out in a campaign.

Which incorrectly makes it sound like both candidates have even thrown out some bullet points. John McCain’s arts policy is apparently not to have one. His website doesn’t mention the arts, arts education, or federal arts organizations like the National Endowment for the Arts at all. His stated education policy makes no mention of the arts at all. I have a hard time trying to imagine an issue that would matter less to McCain and his campaign, much less to a McCain administration, and when the campaign can’t pull together a comprehensible policy for technology and the internet, an articulated arts policy seems unlikely to come during McCain’s lifetime, even.

In place of any official position of the McCain campaign, I took a look at the GOP’s 2008 Party Platform. Which turns out to be a kind of grass roots/YouTube stunt to allow everyone to write the platform together. Interactively! There are five submissions that mention the arts. One is a cutnpaste 10-point “bipartisan” position paper from Americans for the Arts.

John from Damon, TX recommends eliminating most cabinet-level government departments including the “department of veterans affairs (I think the world of our veterans, but they don’t need a cabinet position), and if you need more, take out the department of engery (they haven’t done anything use full to date). then turn our attention to social programs. Most should be eliminated over time. Grants to the fine arts should be eliminated NOW (including PBS).”

Two others mention liberal arts in school, and then there’s Stephen from Coopersburg, PA:

I would like to see martial arts added to the standard curriculum in schools, Not only because I teach Tae Kwon Do to kids age 4 & up, (and that would be a sweet job) but because it teaches them to focus, helps them with agility, and cardiovascular training, instills self confidence, dicipline, and teaches them how to overcome obsticles & fear (as well as kick Butt if needed).

I don’t see McCain’s folks improving significantly on these proposals, frankly. I think they should just go with these.

As reported on Artsjournal, Barack Obama does have an arts policy, freshly drafted by a 33-person arts advisory committee. The policy, grandly titled “A Platform In Support Of The Arts,” [pdf] closely mirrors the issues championed by the Arts Action Fund, an advocacy group and PAC associated with Americans for the Arts that’s hosting the document. It’s a tiny bundle of noncommittal platitudes and proposals [“reinvest in arts education,” create an inner city “artists corps”], expressions of support for existing programs [public/private school partnerships, the NEA], general campaign issues that impact the arts world [universal health care, US stops acting like a total dick to rest of world], and a tax code tweak proposed by Senator Leahy that lets artists donate works to museums at fair market value. That’s it. You feeling the Obamamentum yet?

The advisory committee, too, seems as slight as the platform they propose. It’s headed by the veteran producer/director George Stevens Jr., whose name you might recognize because he was an uncredited PA on two of his father’s landmark films, Giant and Shane. His own work tends toward the Kennedy Center Presents programs, celebrations of what passes for culture in Washington, DC. The other co-chair is Margo Lion, the Broadway producer behind Hairspray. Then there’s Michael Chabon, and a raft of arts industrial complex types: foundation directors, a few philanthropist/trustees, arts council and university folks. Despite the prominence of the artist tax deduction–it’s the only legislation in the proposal–there doesn’t appear to be a single person affiliated with a museum or associated with fine art.

update: poking around Americans for the Arts’ website, I found ArtsVote 2008, an attempt to raise awareness during the presidential campaign and conventions for the arts industrial complex. There’s a page with links to policy statements by all the candidates. All the candidates who responded and submitted them, anyway. Which is to say Obama has three statements. McCain, none. Also, John Baldessari made a poster.