It is not clear how the Oracle at Delphi worked. One day a month, except in winter, the priestess, known as Pythia, entered a sacred chamber, perched on a gilded tripod, peered into a bowl of water from an enchanted spring and, imbued by mystical vapors with the *enthusiasmos*, or divine spirit, of Apollo, she answered the urgent questions of the faithful. The Oracle was the most powerful public figure in the Ancient Greek world. No military or public policy decision was made without consulting her, and she was always right; any unwanted outcomes were attributed to mortals’ failure to properly interpret or follow the Oracle’s predictions. Centuries of Pythian pronouncements are recorded. For a long time they were in iambic pentameter. Then they switched to prose. Some accounts had a lucid, forceful Pythia dropping these pure rhymes herself. In others, the possessed priestess’ utterings seemed incomprehensible to all but her handlers, a coterie of priests known as the *hosioi* who, one would say, translated the prophecies.

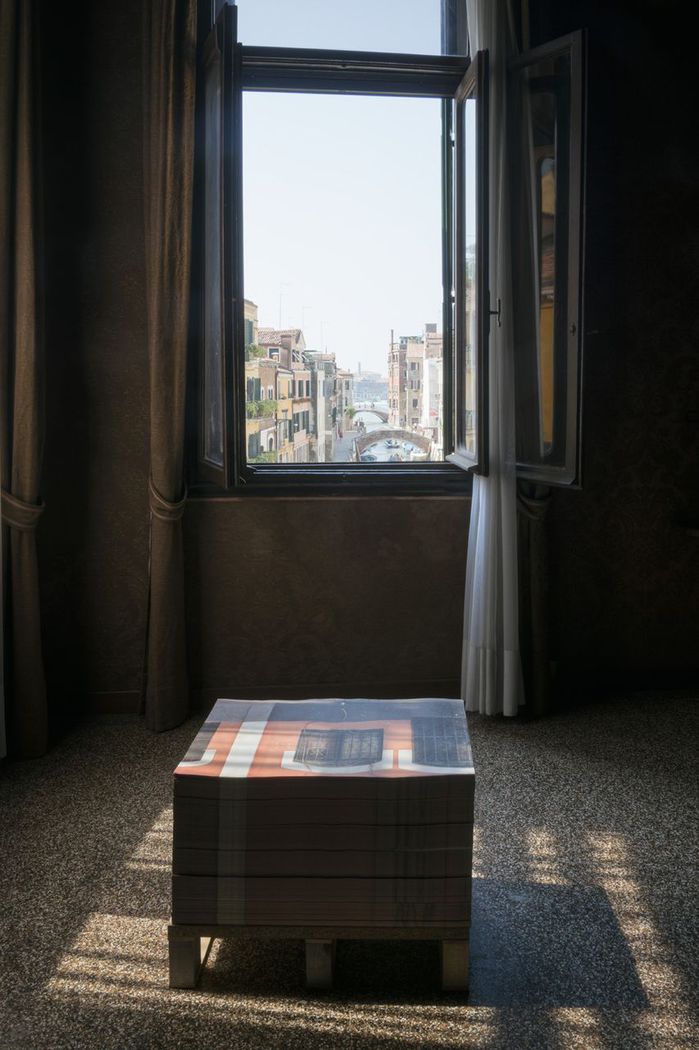

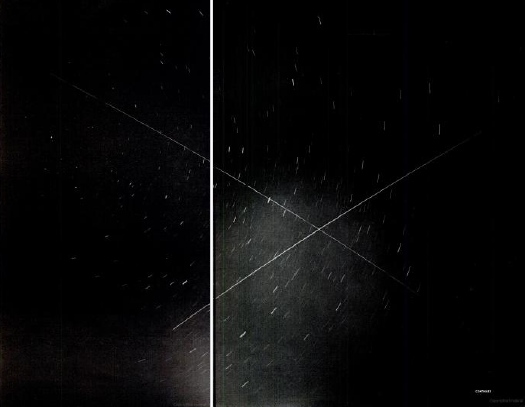

*Elephant Child* is a book about Camille Henrot’s 2014-15 exhibition “The Pale Fox”. Very much like *Grosse Fatigue*, Henrot’s extraordinary video from the 2013 Venice Biennale, it explores humans’ attempts to understand the universe, and it marvels at the structures this inevitably impossible effort yields. It here can refer to either the book, or the exhibition. Henrot suggested thinking of *Grosse Fatigue* as a history and “The Pale Fox” as a geography, which I guess makes *Elephant Child* a map. They are three incarnations of Henrot’s universal narrative, all in one, one in all, a trinity.

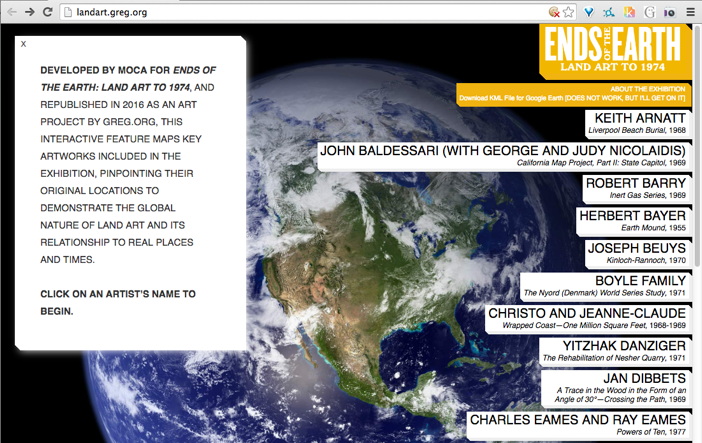

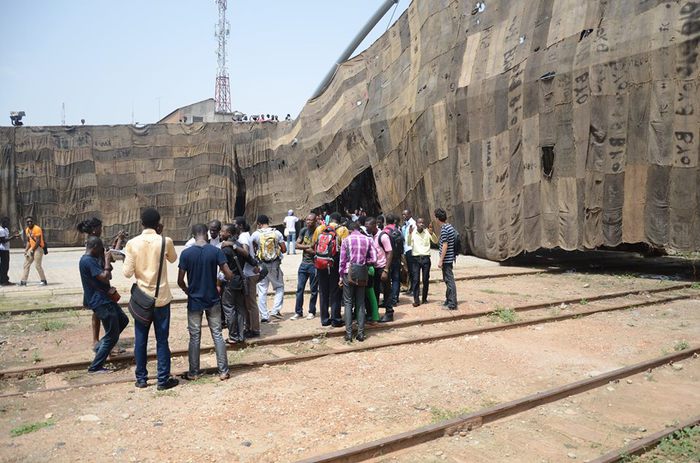

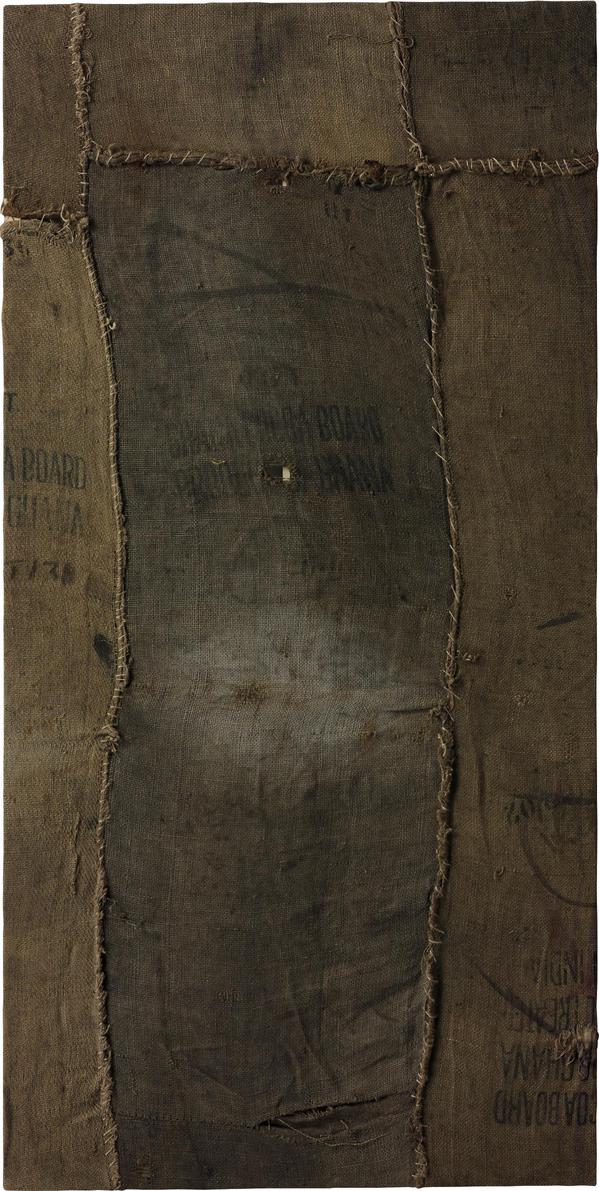

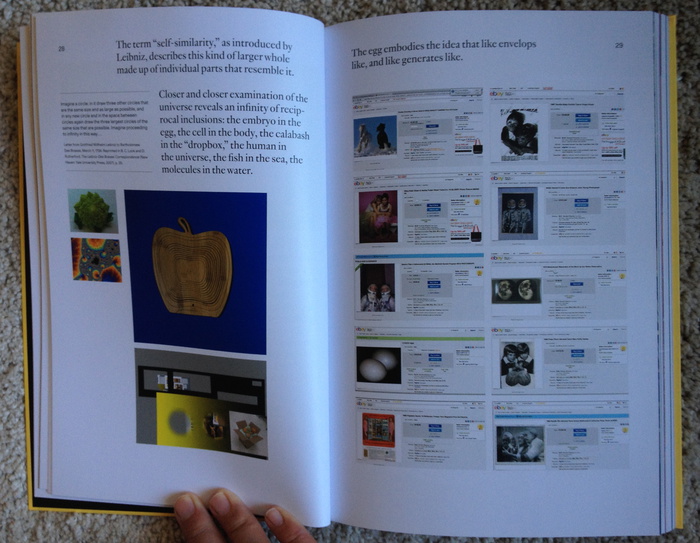

Literally. Many screenshots from *Grosse Fatigue* are woven throughout the book, as is the video’s lyrical poem, performed by Akwetey Orraca-Tetteh and created in collaboration with Jacob Bromberg. Ideas and references from *Grosse Fatigue* also abound, particularly Henrot’s foundational experience as an artist fellow at the Smithsonian, where she captured traces of the museum’s conflicted histories through taxonomy, evolution, colonialism, anthropology, and religion.

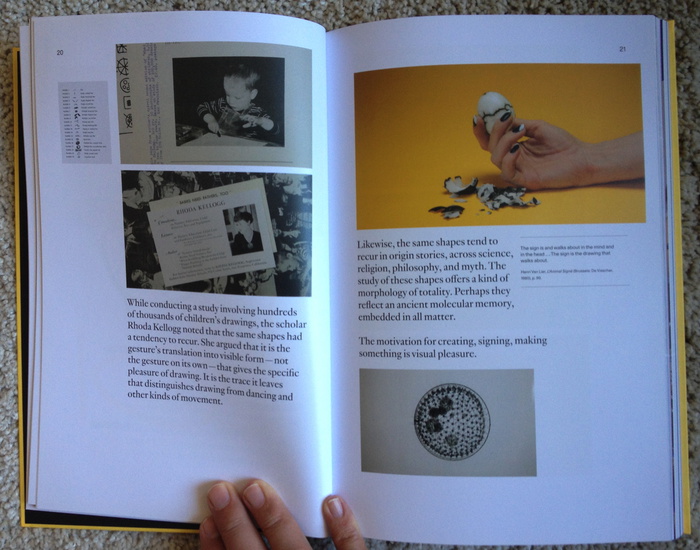

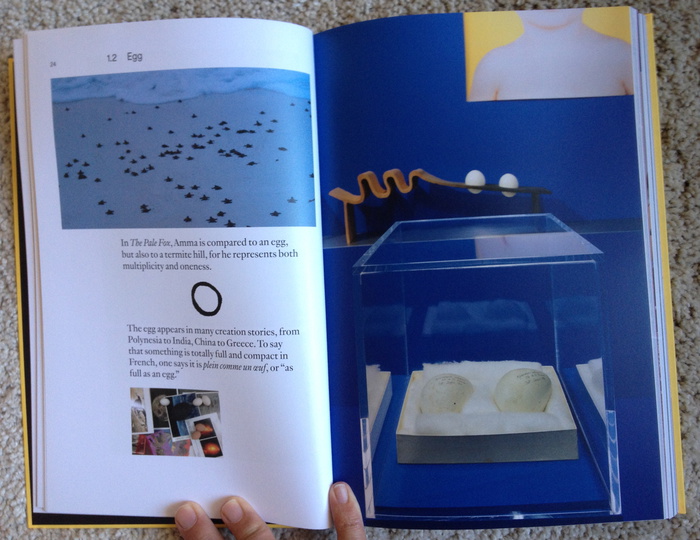

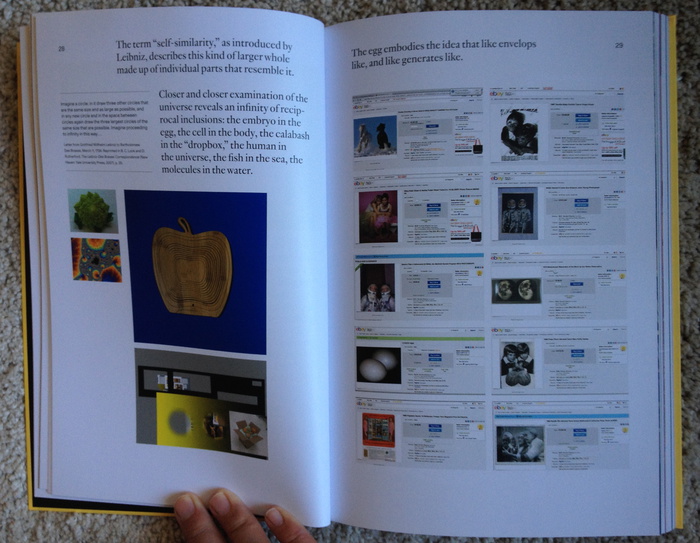

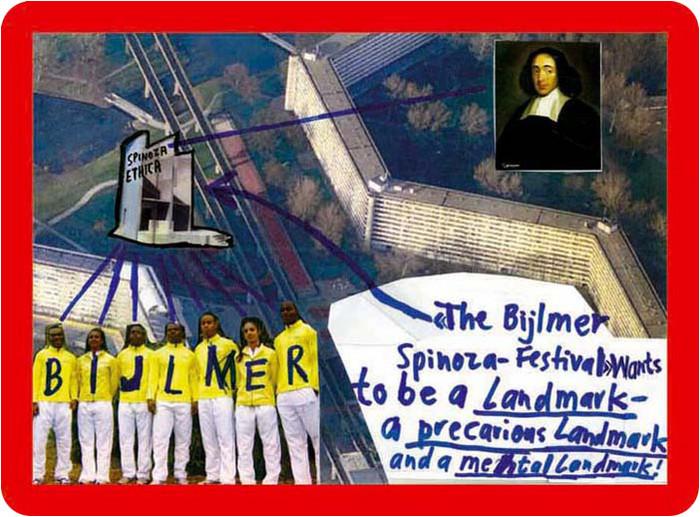

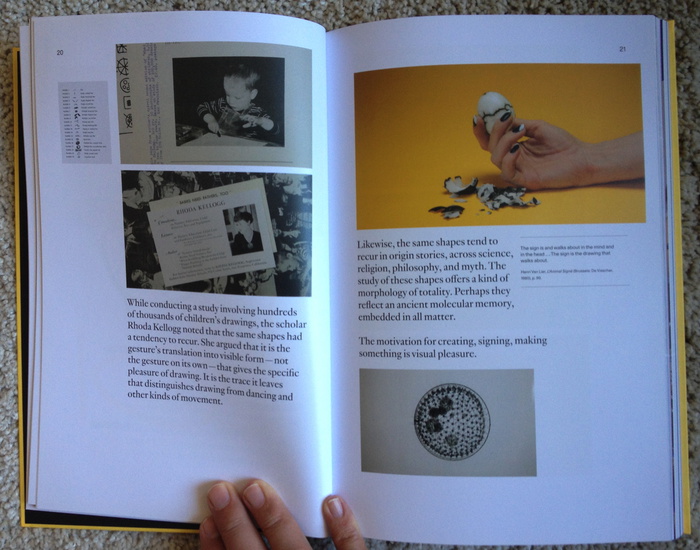

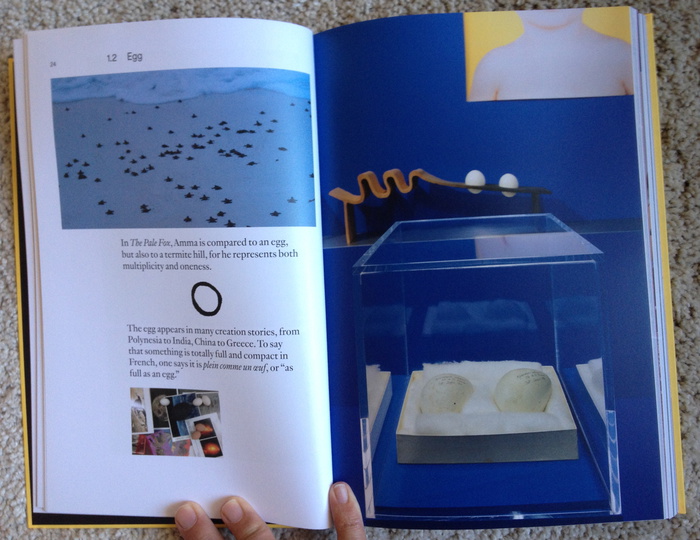

*Elephant Child* begins by holding up a compelling example of what we should be more cautious of calling an origin myth. The Dogon people of Western Africa tell of Amma, who created the universe, his twin, by drawing. The chaotic eighth of their four pairs of twin offspring rebelled, bringing disorder to the universe, but also creativity. He was Ogo, The Pale Fox. Henrot eagerly mined this cosmology for motifs that recur across origin myths-eggs, twins, recursion, primordial drawings-even as she acknowledges its credulous source: a blind Dogon hunter named Ogotemmeli, who reportedly wound out the tale during a long conversation with two white French anthropologists, Marcel Griaule and Germaine Dieterlen, who published it as a book in 1965. The book was called *The Pale Fox*.

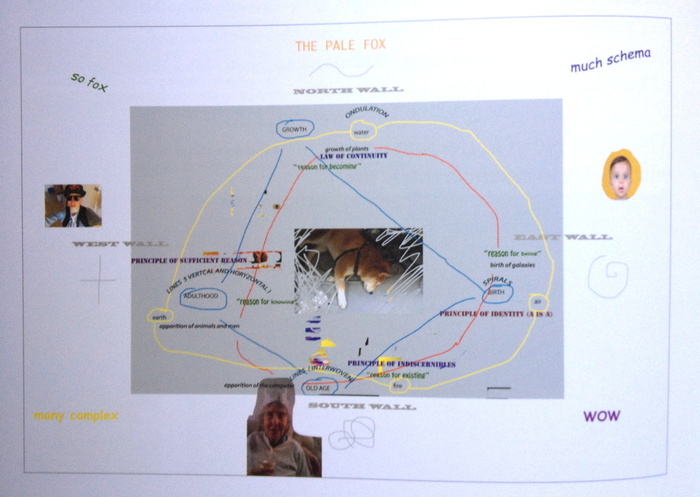

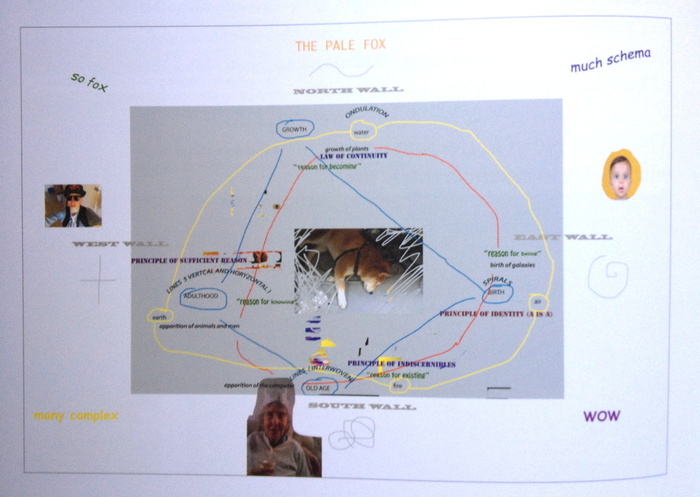

In its function as an exhibition map, *Elephant Child* traces Henrot’s process of identifying structures, and then translating them into schema. The intersection, or collision, of various schema produce the conditions under which the exhibition takes shape. As Henrot said in an interview, that is mentioned in, but does not appear in, *Elephant Child*,

I found it interesting to liken the elements related to the different phylogenies of living beings to the organizational systems of James Joyce’s *Ulysses*. When Joyce wrote *Ulysses*, he had organized systems in which a literary style corresponded to a color corresponded to a theme corresponded to a bodily organ. This over-systematization creates freedom, as categories can be understood together as a group or structure that permits arbitrariness. I wanted my exhibition to have this same freedom.

Dogon meets Doge

Dogon meets Doge

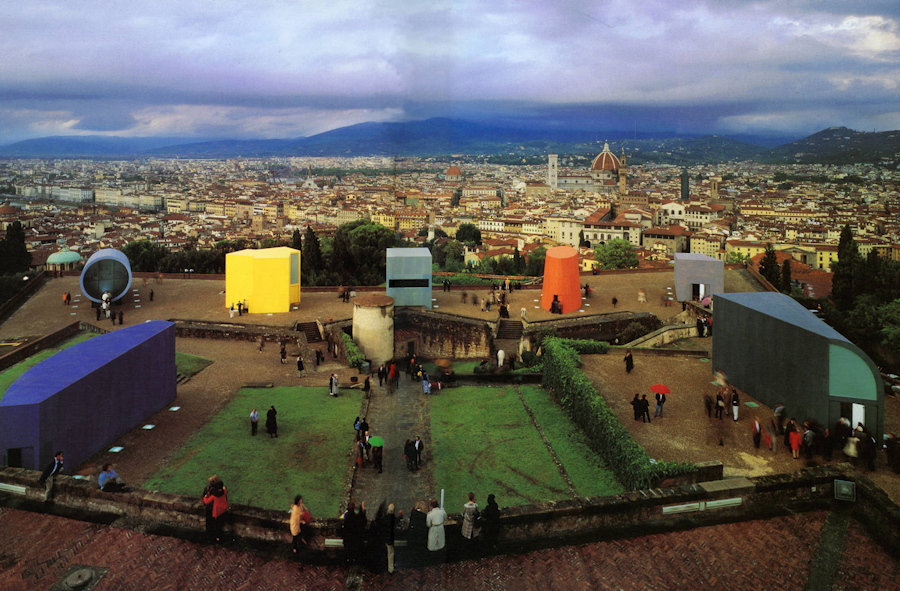

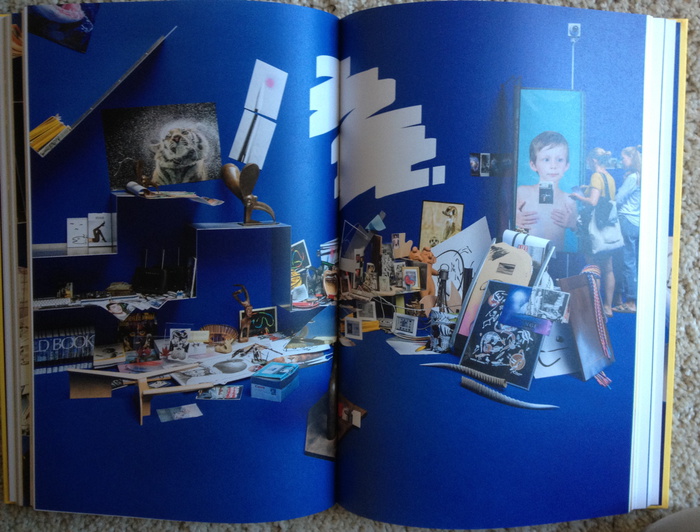

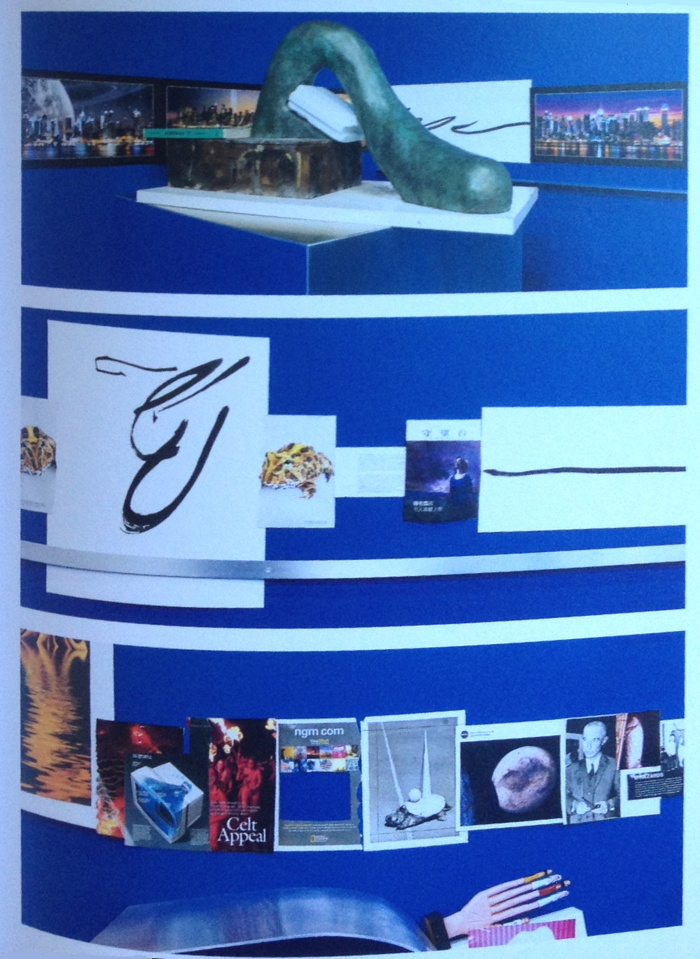

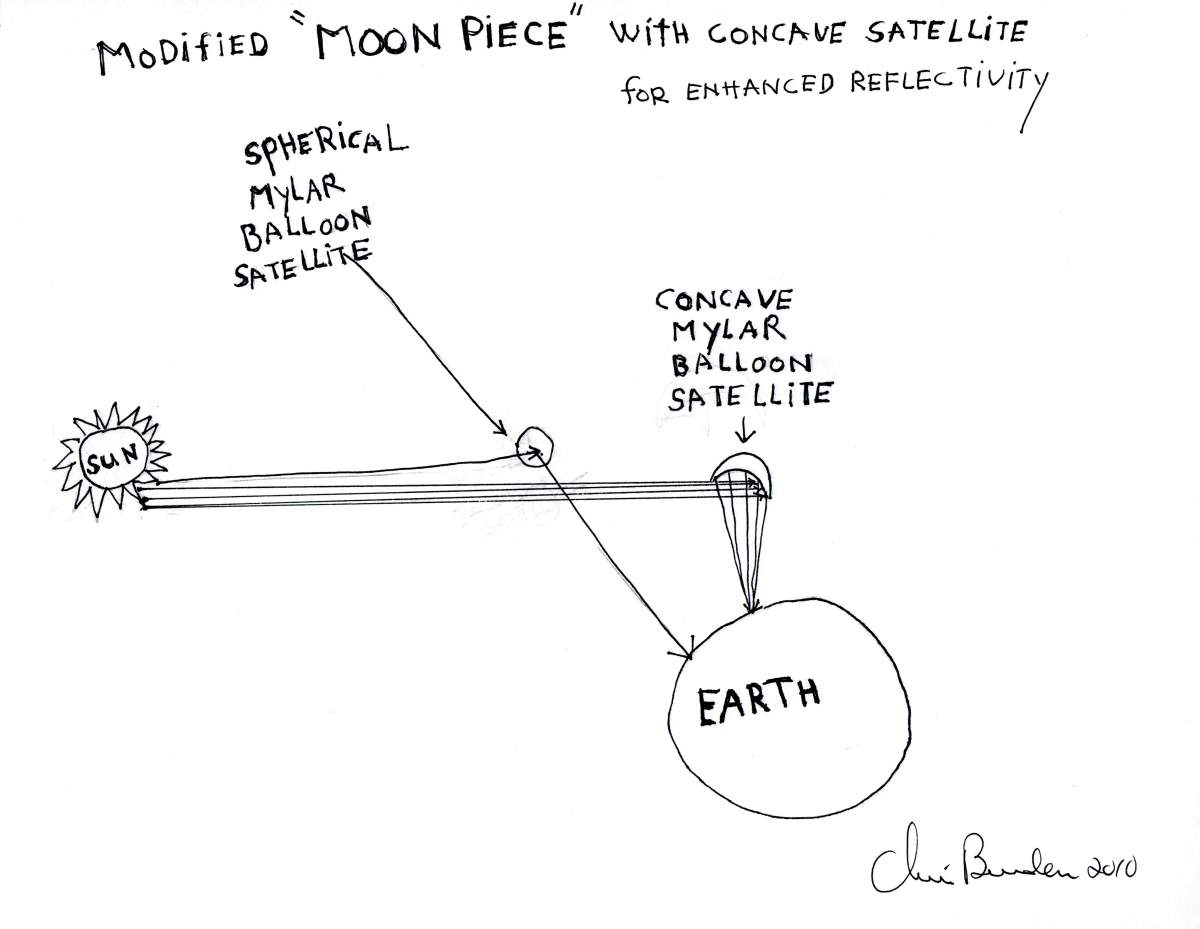

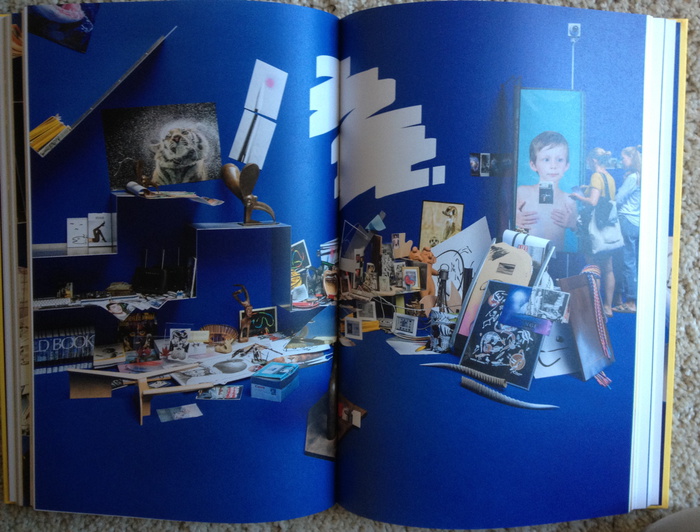

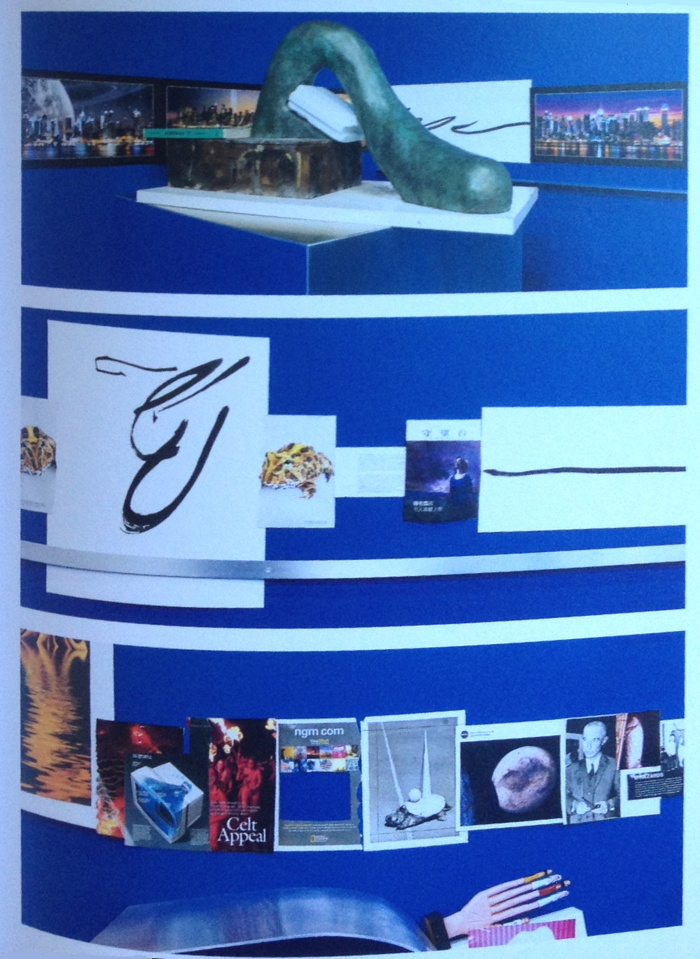

And so Henrot lays four chronological stages intuited from Leibniz onto the cardinal points of a compass in a rectangular gallery-a shape representing man, for God is a circle. The walls and floor are painted chromakey blue and encircled by an undulating, sculptural shelf, suggesting a timeline, of polished aluminum, which is piled with metaphorically resonant objects and images:

There are photos of my family and photos I bought on ebay…and there are different kinds of magazines, advertisements, leaflets, things I picked up in the street, things I bought. The images and the objects have very different statuses…I chose lots of embarrassing objects, because I wanted to focus on clutter-all the objects that you don’t know what to do with, but you don’t dare throw out.

What did not occur to me until I got to the very end of the book, and only then because I’d just seen one appear at auction, is that among these hundreds of objects are Henrot’s own works of art. This category is mentioned once in Scepanski’s intro, and nowhere else, until you get to a checklist of works, which turn out to be the only objects mapped onto the show’s schema. Rather than a *gesamtkunstwerk*, then, Henrot’s show, and its elaborate conceptual confabulations, are a context, a framing, for the production and presentation of her own art. Which here includes dozens of Zen-ish ink drawings that approximate Amma’s generative marks, and bronzes that echo either exoticized artifacts or postwar desktop abstraction. None of which is ever discussed.

Or maybe it is.

Maybe this book not only maps the arbitrary folly of inevitably subjective systematization that gave the show its premise; it instantiates it. It’s its own recursive cautionary tale, a *Gödel, Escher, Bach* of Henrotian Systems Theory, and turtles all the way down as practice. And the art is the result.

Henrot is trying to be the fun, free, arbitrary elegance she wants to see in the chaotic world she consciously over-systematized to the point of collapse.

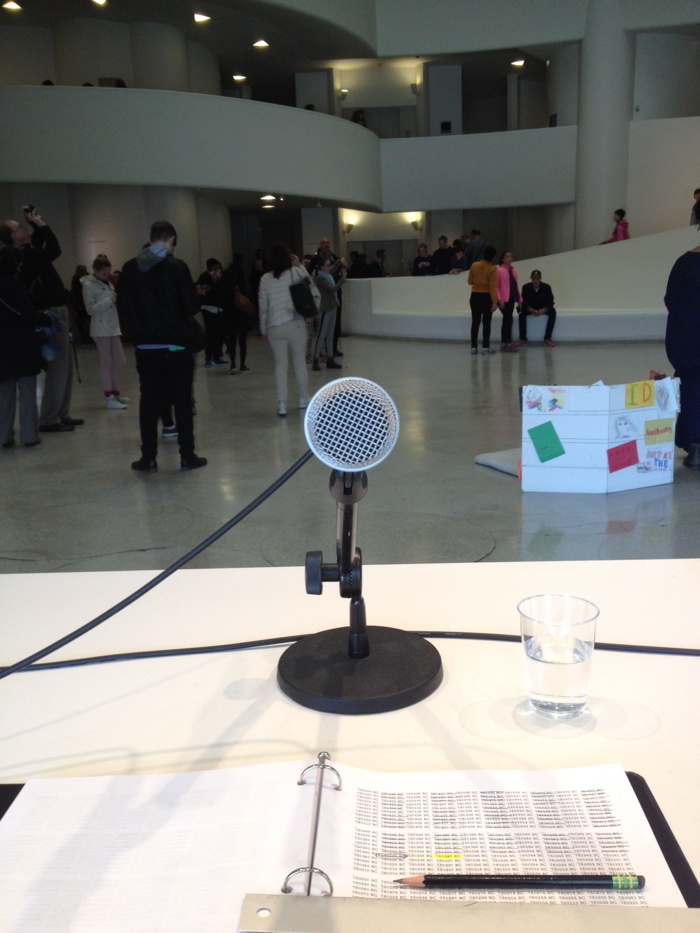

The only place I’ve seen Henrot discussing her art per se is an interview with Rachael Vance last winter during the fifth and final installation of “The Pale Fox”.

[CH] I spend a lot of time looking at the objects on my desk. Also, when I go to the doctor I am fascinated by what they have in their waiting rooms, on their desks, and the way these things are placed. The objects are supposed to represent power but they are also ridiculous. More often than not, the doctor will have one of those huge tape dispensers, which just look so silly. Every time I see them, I always think:

“Why would you have a tape holder that takes up all this room? Wouldn’t it be more elegant to have a small tape in your drawer? And wouldn’t it be even more elegant to just do everything on your iPad?” One day perhaps things like that won’t exist anymore, who knows. Most of the bronzes in “The Pale Fox” were conceived out of this process in which we try to introduce rationality to something that is fundamentally irrational.

…

[RV] Compared to the rest of your material in “The Pale Fox”, your sculptures stand alone as very substantial yet quiet pieces. Do they represent some sort of therapy for you?

[CH] It’s true that they have a very different energy from the rest of my work. When I think about the exhibition, I think that energy came from a sense of anxiety. However, the sculptures came from a more playful and distant part of myself. When I start making a sculpture and stop having fun, I stop making the sculpture and move onto another one. In a way, there is this part of my work that is very disciplined and almost masochistic. The whole process of buying five hundred items on eBay and doing these charts and maps and studying them is a little mad. Just making the list for the exhibition was a headache. It was the same with *Grosse Fatigue*, writing the voice-over was such a long process. Editing the images was a nightmare and my assistant and I became really sick. There was a super-long list of different footage lines because there were more than 25 images running simultaneously. It was really crazy, but I guess I’m driven by this idea of going mad by trying to produce the impossible project.

The actual genesis of “The Pale Fox” is not clear, but it appears to follow (from) *Grosse Fatigue* and its success. The screenshots in the book show most of the ebay photos shipping in November 2013. Most of the sculptures date from 2014. So this kind of object making seems relatively new for Henrot, who previously favored film and had been skeptical of the artist label.

It is probably speciously late of me to note Michael Connor’s explanation from the preface that the main text of *Elephant Child* was “initially narrated by Camille to curator Clara Meister over a period of several days.” It is an “intellectual framework,” a “set of ideas as carefully crafted as any of her works,” that also comprised, on Connors’ part, “a certain amount of panic” and “scissors and tape.” In her introduction Westphälischer Kunstverein curator Kristina Scepanski credits Meister and Connor as co-authors of Henrot’s text. All three, along with Bromberg, are also the book’s co-editors.

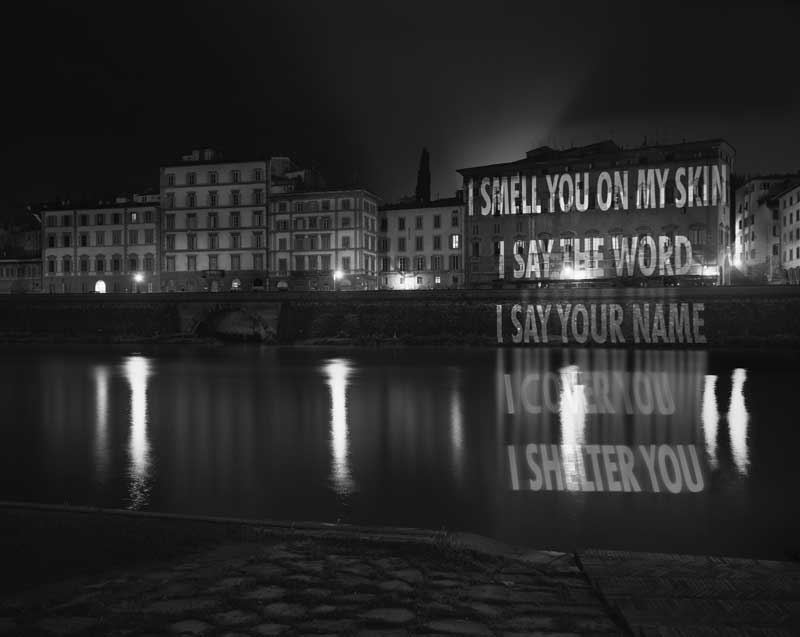

I did not see any installations of “The Pale Fox” in person, but like so many others, I was utterly transfixed by *Grosse Fatigue* and remain so. It remains a remarkable, ambitious, challenging, and beautiful work, and I continue to marvel at its making. *Elephant Child* communicates that essence-and much of the content-in book form. But it also captures the multitude of overlapping systems and the many talented people assembling in the wake of Henrot’s triumphant Venice debut. It documents at least a part of the structure that grows around an artist to sustain a career, or a practice, that might, one hopes, survive the chaos that yields such works again. And if a crowd of *hosioi* decrypting Henrot’s pronouncements and wan ink drawings and elegant bronze pleasure objects are what it takes, then so be it.

Buy *Elephant Child* from Inventory Press, or on Amazon [inventorypress.com]

Order from Chaos: Interview with Camille Henrot [sleek-mag]