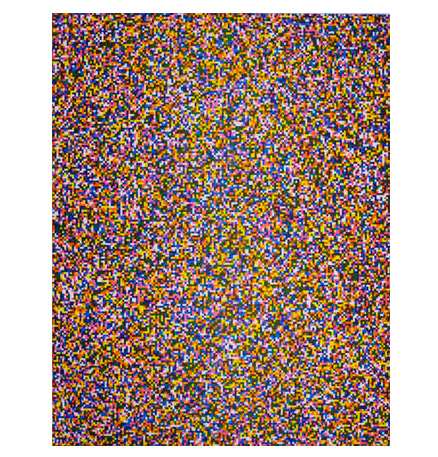

I’d seen Tauba Auerbach’s text- or letter-based paintings before, but I didn’t know about her prints. She did a couple of pairs of prints using pixels last year with Berkeley-based Paulson Press. There’s a black and white set, 50/50, where exactly 50% of the pixels shown are white and 50% are black, and then there’s an 8-color set called A Half Times A Half Times A Half.

Without knowing how or why they were made, I was first drawn to the different resolutions, which she calls “fine” [above] and “coarse” [below]. [And the color ones obviously remind me of Gerhard Richter’s Farben painting series from the early 1970s, which became the basis for his stained glass window in the Koln Cathedral.]

Then I realize they’re aquatints, etchings–Paulson Press specializes in intaglio printing–and not printed digitally, so there’s an interesting transition from digital to physical. And the printing technique itself adds a layer of imperfection to a “perfect” digital original.

Of 50/50, Auerbach said [pdf]:

I was thinking about binary as a language, like binary code for computers, as well as just the binaries within the English language, and how in binary code there’s just zeros and ones.

You have to represent everything, including the ambiguous, with just those two components.

So she’s started introducing randomness. The b/w pixels are randomly placed, but it really pops in the color etchings:

I created three plates. And these three pigment primaries are like the process primaries used for printing –cyan, magenta, and yellow. And on each plate there’s a random pattern of colored squares and blank squares, and they overlap at varous probabilities to create seven possible colors–or eight if you include the white. So, the three primaries, the three secondaries, and then a seventh color where all three overlap, and then the white where none overlap.

So if I’m reading that right, each plate could be printed with any of the three colors. The plates x inks would generate a the number of permutations–though it’d be doubled if the top and bottom of the rectangular plates are reversed.

As I’m typing this, it sounds like a Sol Lewitt, too, an early, exhaustive Lewitt serialization made in the mature Lewitt’s palette. But there are at least 84 possible combinations for each print–if the top/bottom of each plate don’t matter, there are 816–and Auerbach’s edition size is only 30. Sounds like introducing a bit of randomness into the process was plenty. I’m sure her printers were relieved.

Tauba Auerbach prints [paulsonpress.com via 16 miles of string]

Tauba Auerbach prints press release – pdf [paulsonpress.com]