Jetty, dir. Skylar Nielsen, starring Julian Sands

RadioWest, the local public radio talk show on KUER in Salt Lake, devoted an hour to Spiral Jetty this morning. Most of the time was spent talking with art historian Ann Reynolds, Dia’s Jetty curator and Utah liaison Kelly Kivland, but there were segments from local earthwriter Terry Tempest Williams and director Skylar Nielsen. It was the debut of Nielsen’s short film Jetty, commissioned by KUER, that was the hook for the discussion. Jetty had been conceived and shot one morning in September when the actor Julian Sands was coming to town to do Pinter, and he wanted to visit the artwork, which he’d heard about from his friend in LA, Michael Govan.

But this is all backing into the story. Which nonetheless feels necessary, because it was a fascinating and perplexing conversation that, the main guests’ credentials notwithstanding, felt utterly detached from the art [historical] context, and its theoretical discourses. Instead of that construct, Spiral Jetty exists, in a public place, in the open, in a culture, and that is Utah. Utah is the site. Which makes the art world the non-site, I guess?

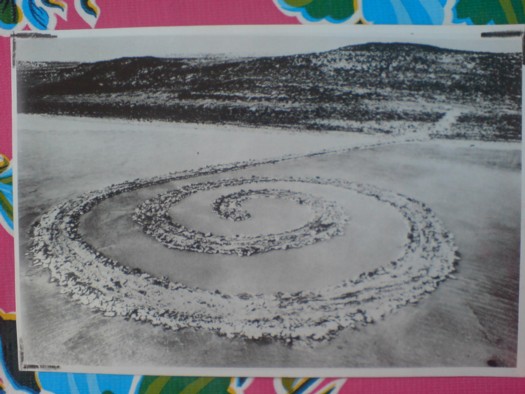

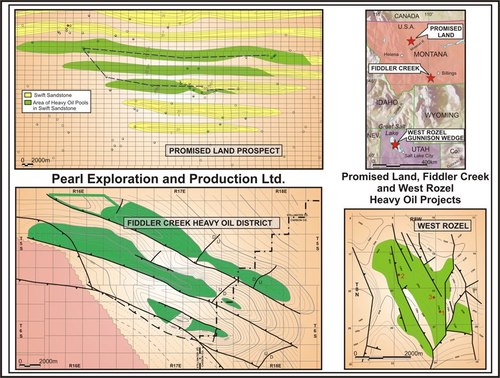

First, they didn’t discuss Robert Smithson’s film Spiral Jetty at all. Reynolds made one reference to a photo of oil derricks, but that was it. Which is amazing. In 1993, the last year before it resurfaced, curator Robert Sobieszek wrote of Spiral Jetty “coevally manifesting itself as a sculpture, a film, and a text,” In practice, though, for two decades, the film was the work; the site was irrelevant. This perspective reflected the physical reality of the submerged, i.e. basically lost/destroyed, sculpture, far off in BF Utah, which, New York and the art world were central, check out the view from up here, and Utah’s marginality was the self-reinforcing reason Smithson had picked it. With the re-emergence of the jetty, the enlightened pilgrimage through the chain restaurant cultural desert to the abandoned, entropic wasteland kicked in.

If this morning’s discussion was any indication, Spiral Jetty has been pulled to Utah’s bosom and squeezed, hard. Redeemed from its oil-drilling & tar-seeping failures, it is a manmade monument at one with nature that offers spiritual solace and communion with the land, sky, and water. It is experiential above all, an engine of personal transformation and enlightenment for all who walk or contemplate it. Reynolds’ top tip for visiting Spiral Jetty is to camp out there. And if you can’t at least spend 24 hours. Kivland, whose first visit to Spiral Jetty was in October 2011, with Nancy Holt, as part of the lease renegotiation process, agreed, and committed to visiting for the long haul. [Note: there are no facilities for camping at Spiral Jetty, and all the land you hike on is privately owned. Is Dia contemplating some infrastructure to turn Spiral Jetty into a more Lightning Field Experience?]

Smithson’s pseudo-mystical writing is used to support this reconfiguration of Spiral Jetty into a devotional labyrinth for psychic discovery. Tempest-Williams gave perhaps the most highly evolved expression when she talked about how the submerged Jetty gave her solace when her mother died in 1987, and how walking its re-emerged path with her adopted Rwandan son gave courage that life will go on when she finally visited it, in 2011. Which, girl? That thing’s been out since 1995, and yet you didn’t go until 2011? I’m two degrees from Tempest-Williams and respect her and her work, but this strikes me as a pristine example of her ability to refit something, anything, into a deeply felt reflection on the landscape of her self.

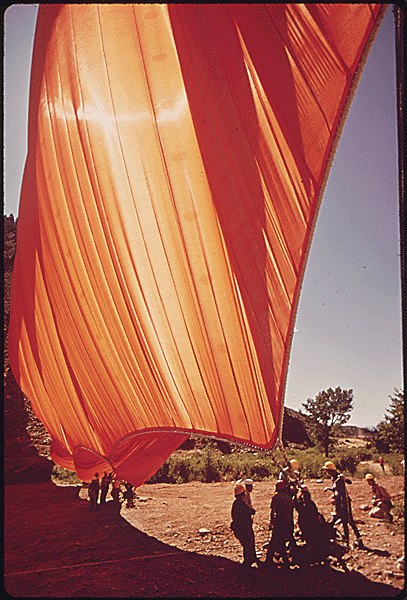

Or maybe the apotheosis here is actually the Jetty film, created seemingly on a whim, with a helicopter and a dronecam, when the radio folks heard their famous actor/guest wanted to visit the site. In 3-minutes Nielsen puts Smithson’s film through a Fincher filter, with distorted titles, non-spatial edits, and Sands trudging around the landbound jetty, literalizing the Smithson text he intones in a voiceover:

On the slopes of Rozzle Point

[AERIAL SHOT OF SLOPES]

I closed my eyes and

[CUT TO FAST ZOOM ON SANDS STANDING AT APEX OF JETTY, EYES CLOSED, ARMS OUTSTRETCHED TAKING IN THE]

the sun burned crimson through the lids.

[ZOOM TIGHT ON HIS FACE]

I opened them

[SUDDENLY OPENS EYES]

and the Great Salt Lake was bleeding scarlet streaks.

Then “improvising as he saw fit,” Sands begins reciting lines from “The Windmills of Your Mind”:

Like a circle in a spiral

like a wheel within a wheel

never ending of beginning

on an ever-spinning reel

It reminds me of nothing so much as Sands’ portrayal of George Emerson in A Room With A View, who climbed a Tuscan tree to shout his creed and the Eternal Yes to Nature herself.

Actually, I saw A Room With A View as an impressionable freshman in Salt Lake City, though I wanted to be Freddie. And I was the only one in the packed theater to laugh out loud at Daniel Day-Lewis’s garden party scene. I may have to reshoot this movie.

Oh man, or just mash it up.

“Mr. Sands, Mr. Nielsen, and Mr. Fletcher fly out in helicopters to see a view. Utahans fly them.”

“I have a theory,” said Judi Dench’s Eleanor Lavish, “there is something in the Rozel Point landscape that inclines even the most stolid nature to romance.”

Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty [radiowest.kuer.org]

Jetty, dir. Skylar Nielsen, starring Julian Sands [vimeo]

Behind the Scenes | Spiral Jetty [vitabrevisfilms]