The stairwell in the entrance to the University of Oregon library contains a large mural, Mission of a University, painted in 1937 by art professor Nowland Brittin Zane, of a quote by another faculty member, Frederick George Young. A social science professor and dean in the 1920s, Young saw the divine mission of a university aligned with the founding principle of Oregon itself: to elevate and preserve the white race.

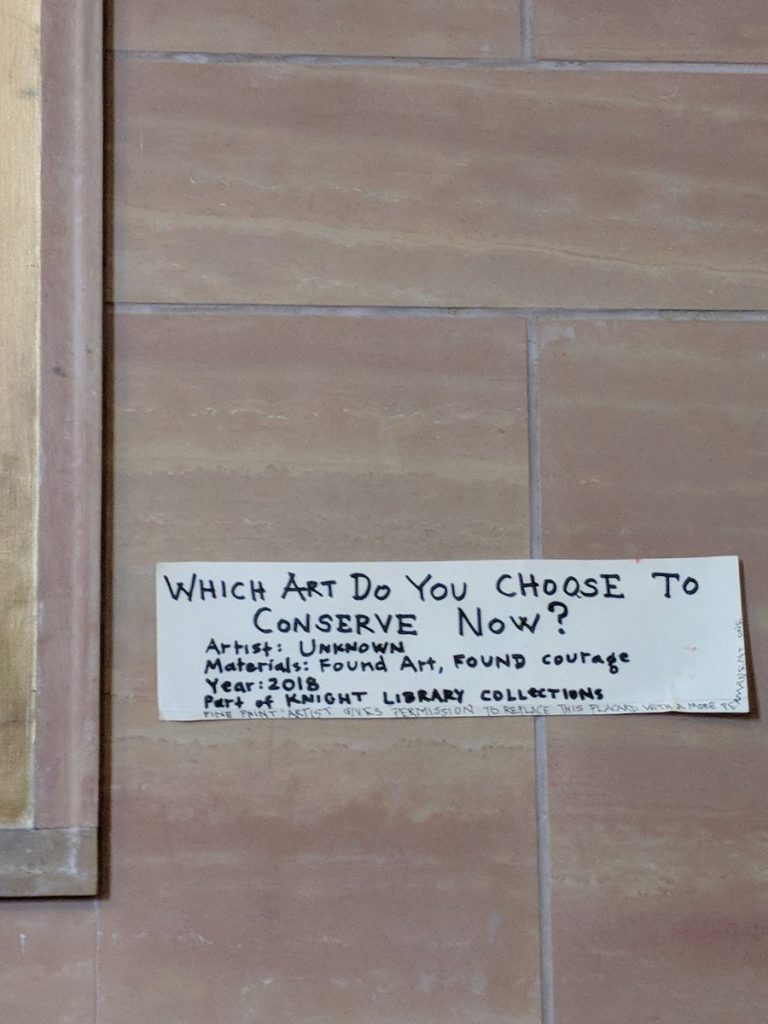

Last night @videodante tweeted out photos he’d received of a fresh painting intervention on Zane’s mural: a slash of red paint crossing out “racial heritage.” As interesting, though, is the handwritten label for the new work, left on the wall [below].

The materials, “Found Art, FOUND courage” are almost as awesome as the title, “WHICH ART DO YOU CHOOSE TO CONSERVE NOW?” Is it the title, or an epic challenge to the institution’s perennial decision of which facts, which history, which brushstroke, and whose heritage are their actions perpetuating? This quote has been recognized as racist and offensive–and has been the subject of critical and activist efforts to remove it–for years. There are at least three spots in the bottom corner of Zane’s painting where conservators chose to erase someone’s addition. So this is one more choice to be made in an ongoing dispute, and the artist knows what is at stake.

The author of this new work, though, offers another solution in a “fine print” addendum, apparently added on the spot, as the text curls up the side of the label. If the library is troubled by impending conservatorial complicity in reasserting white supremacism, the “artist gives permission to replace this placard with a more permanent one.”

What if they just leave it?

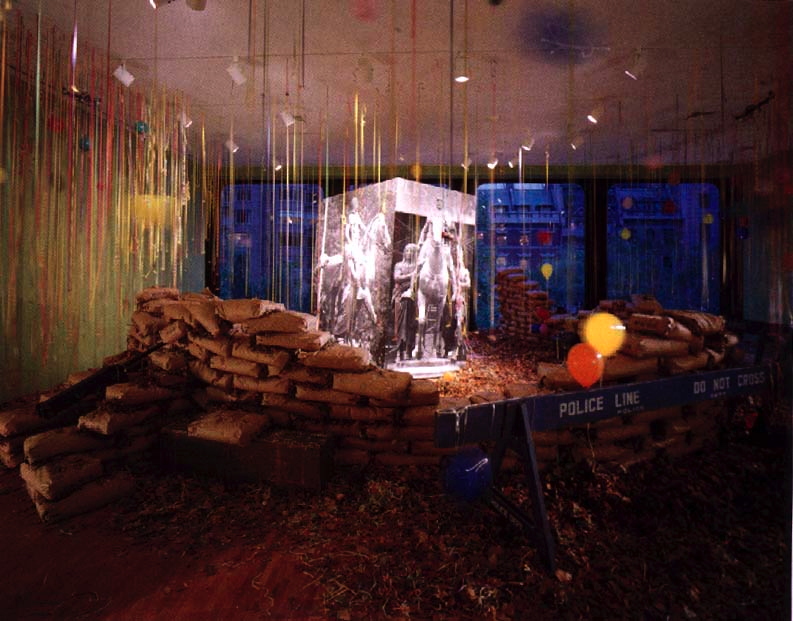

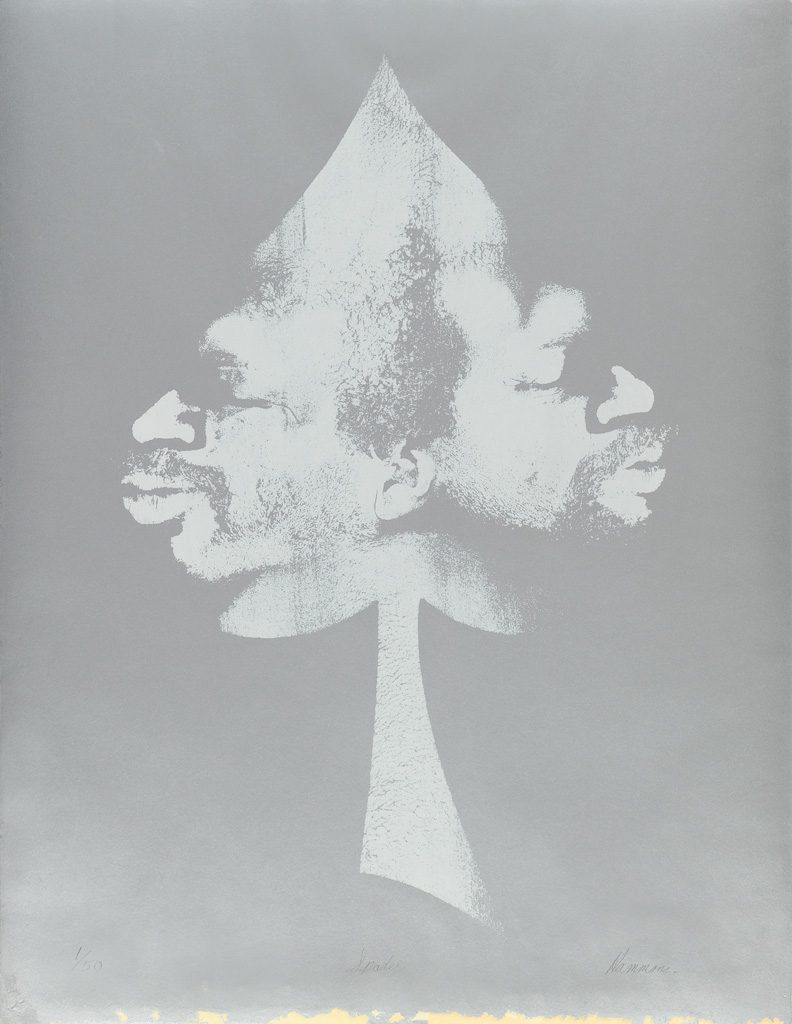

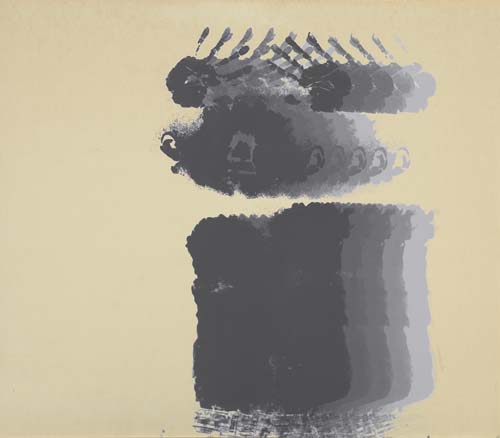

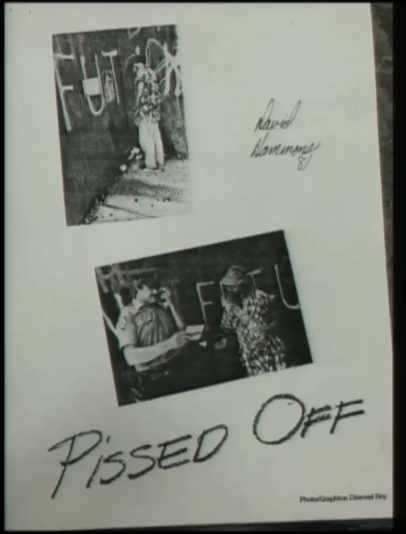

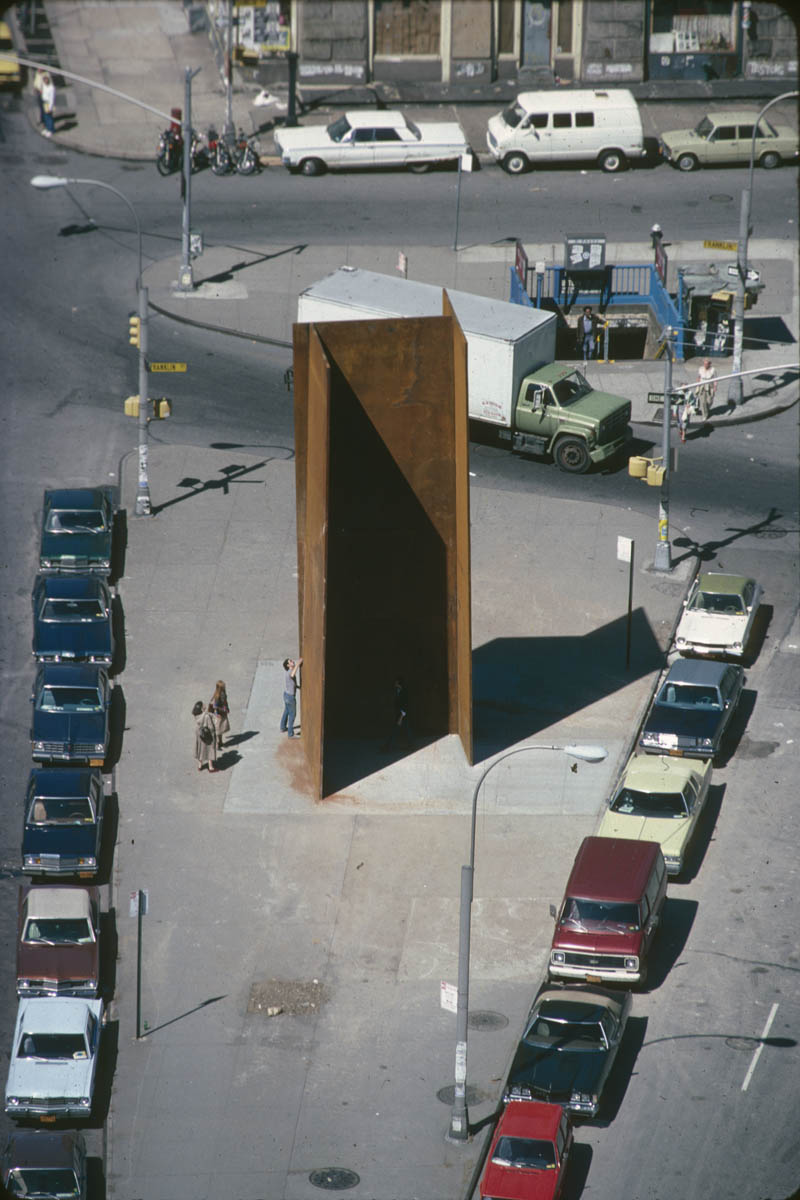

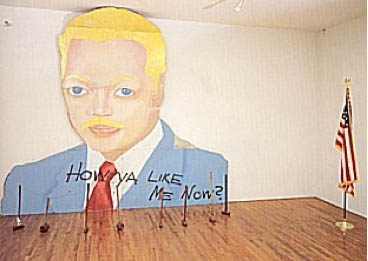

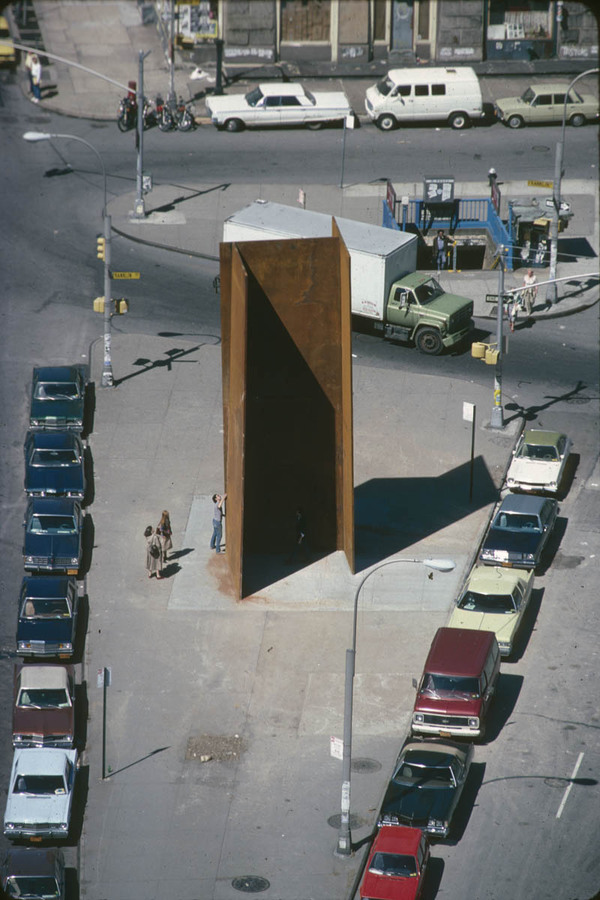

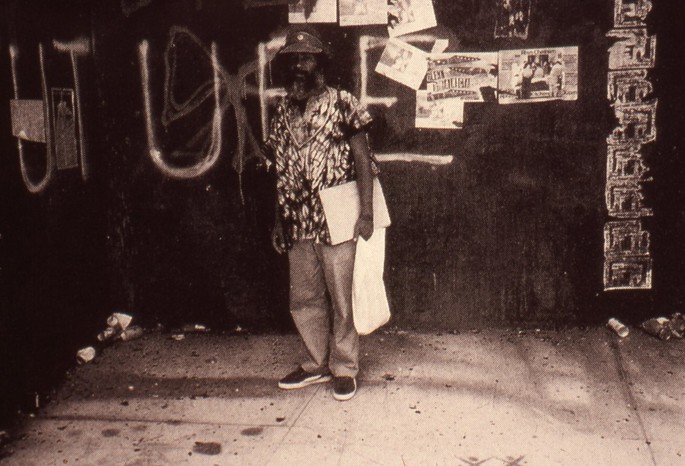

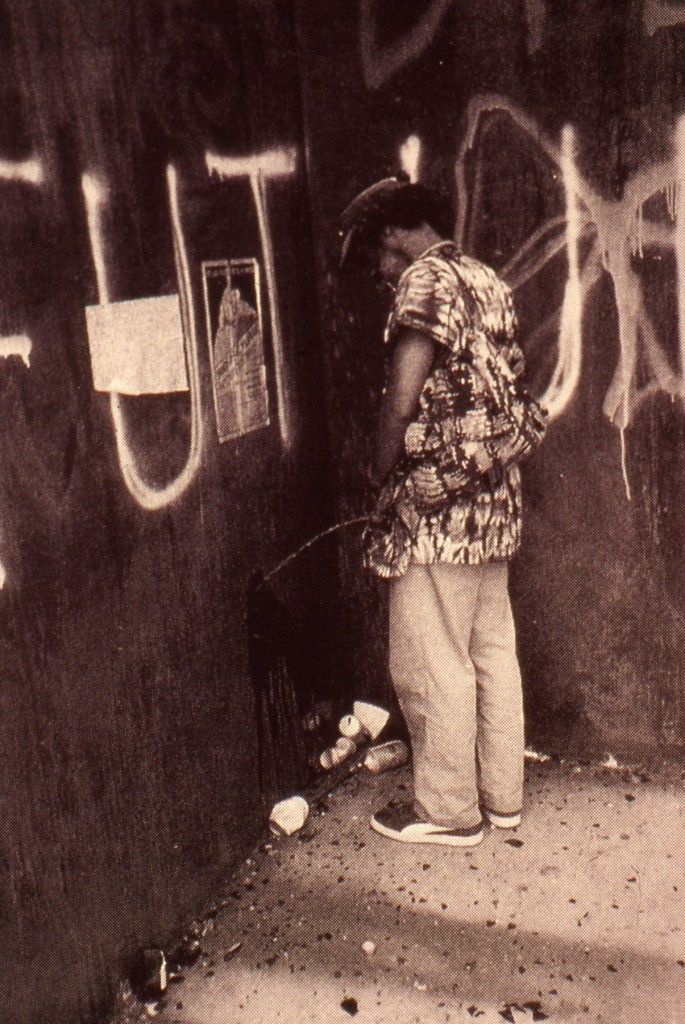

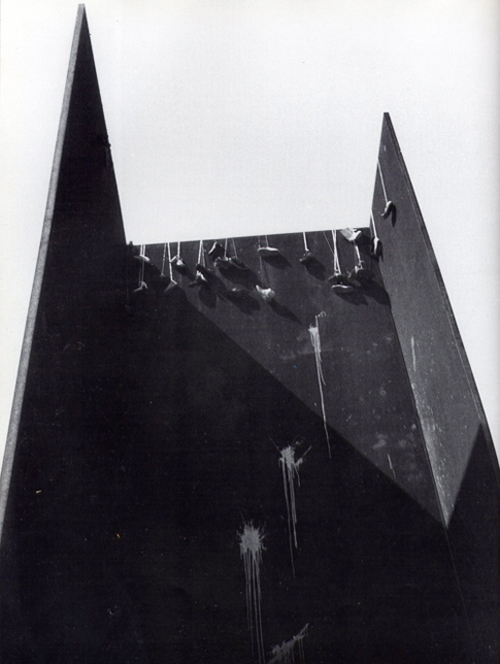

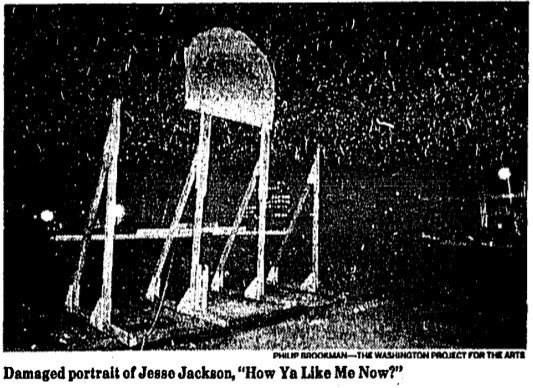

With David Hammons on the brain at the moment, I think of his 1989 outdoor painting of a blonde Jesse Jackson, How Ya Like Me Now? which was vandalized as it was being installed across from the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC. Hammons subsequently showed it with a row of sledgehammers. And of six American Indian activists who painted Theodore Roosevelt’s statue in front of the American Museum of Natural History in 1971, who had their charges dropped if they paid the museum’s cleanup costs.

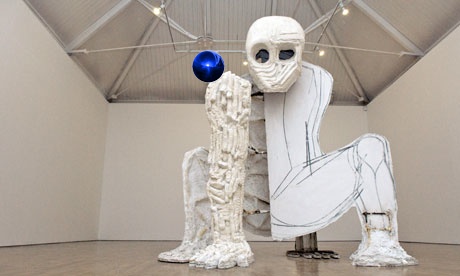

Since the beginning of the Black Lives Matter movement, and the increased protests of confederate memorial statues, I’ve come to see painting as crucial, even central. After decades of inertia, monuments are suddenly painted or pulled down. Then they’re quickly covered with tarps or boxes or removed. Take an object. Do something to it. Do something else to it.

What if we recognize these gestures as generative, not destructive? What if we leave them? Keep them? Look at them? Study them? And when the time comes, conserve them?