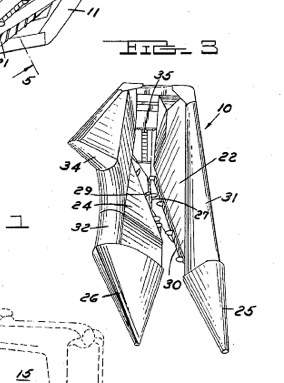

From about 44 minutes into John Ruth’s 1975 TV documentary, The Amish: A People of Preservation comes this picture of a horse-drawn, single-row corn picker in what looks like galvanized steel:

It’s about right here that the sculptural beauty of this machine–I do believe it’s a Dearborn-Wood Bros. single-row corn picker, perhaps a precursor to those designed by Clarence Richey and John O’Donnell in 1956 after Ford bought in the company–starts to sink in:

And as soon as you’re caught up in the unexpectedly futuristic, asymmetrical, jet wing-like, origami-like form,

it’s gone.

On another note, the Amish in 1975 appear to have been a lot less self-conscious about cameras in their midst. I blame Witness.

The Amish: A People of Preservation [folkstreams.net]

Daniel Libeskind And The Grand Academy Of Lagado

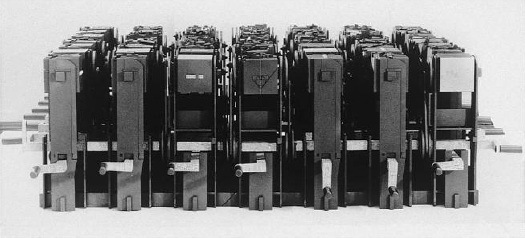

God bless the Internet and all who surf upon her. A couple of weeks ago, I wrote about what I thought was an esoteric topic, even for greg.org: the fantastical lost machines from “Three Lessons of Architecture,” Daniel Libeskind’s exhibition at the 1986 Venice Architecture Biennale.

And yet, within hours of posting about them, I got an email from one of the guys who had been Libeskind’s grad student at Cranbrook and who had built and installed the machines. Hal Laessig is now artist/architect/developer in Newark, and he was gracious enough to share his stories from the “Three Lessons” project, and from Libeskind-era Cranbrook. They range from insightful to hilarious to outrageous, and I’m working on putting our interview together right now.

In the mean time, here’s a clarification about the references for the machine Laessig oversaw, the Writing Machine, which I had incorrectly described as being inspired by Raymond Roussel’s Reading Machine.

As it’s described here, at the very bottom of this ancient article on hypertext, the Reading Machine Roussel exhibited in 1937 was basically a book on a Rolodex. Color-coded tabs helped the reader navigate through multiple layers of cross-references and footnotes. Interesting, but nothing at all to do with the form of Libeskind’s version, which took its inspiration from somewhere else entirely.

Continue reading “Daniel Libeskind And The Grand Academy Of Lagado”

Must Credit greg.org!!

Hey you people, with your dying print venues, muscling in on my action!

“A visit to the show might end with a broad smile at three paintings by Arcimboldo (pronounced Arch-im-BOLD-o)” – Blake Gopnik, Washington Post

“In the current show Mr. Colen (pronounced CO-lin) has made the mistake of ignoring…” – Roberta Smith, NY Times

Nonetheless, they’ve been added to the list.

La Dolce Book Trailer

Wow, if I didn’t worry the ghost of Fellini would come back and smack me upside the head, I’d say the book trailer for Chris Lehmann’s Rich People Things is the The Bicycle Thief of book trailers.

Instead, let’s go with, “It’ll make you say, ‘Hitler in a bunker who?'” That’ll fit on a marquee, won’t it?

The Unoriginal Copy

Dear Art World,

Please arrange the following on a 2×2 grid for me? Or maybe a spectrum? Because I cannot:

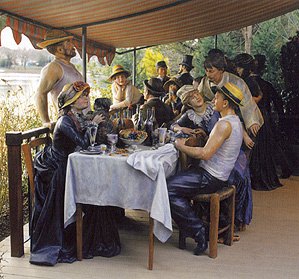

Eve Sussman’s 89 Seconds at Alcazar (2004), which I quite like, but:

Peter Greenaway’s Nightwatching (2007) and his cinematic projections on the Last Supper.

Philip Haas’s 2009 filmic re-creations of five paintings from the Kimbell Museum:

The Laguna Beach Festival of the Arts’ Pageant of the Masters tableaux vivants (1933-present):

Seward Johnson’s bronze re-creations of well-known paintings (1994- too long), such as those shown at the Corcoran in 2003:

And his blown-up re-creation of Grant Woods’ American Gothic (2009):

And the gigantic fiberglass WTF of Philip Haas’s Arcimboldo-ish sculpture that was being installed at the National Gallery the other day?

Having recently made some copies of someone else’s art myself, I really want to know. Because if this is where it leads, I’ll just go back to finance right now.

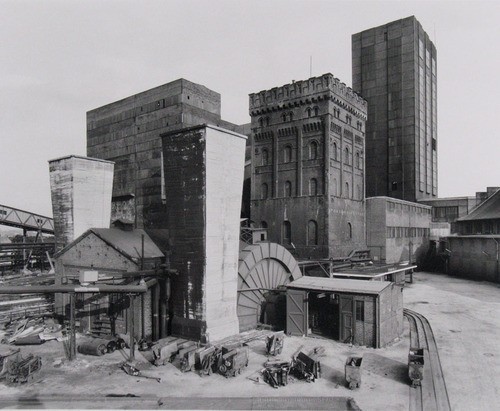

Bernd & Hilla Becher Made A Movie. In Color.

And so far, I can’t find it anywhere:

UEZ: when your work first started to appear and was classified as Conceptual art, did you have a secure visual language which you knew would be viable over time? Or could you have arrived at completely different forms of presentation, or made your photographs the basis for videos?

BB: We did make a film once, on the Hannover mine.

HB: Actually, there’s no need at all to talk about failures.

BB: Because that was such an enormous complex. We made a film about it because we wanted to show the atmosphere. Then we looked at the shots, still uncut, and were totally disappointed.

UEZ: How did you make the film?

HB: We borrowed a 16mm camera from Sigmar Polke. The advisor was Gary Schum, in part, who has made a load of beautiful artist films, with Gilbert and George, for example. The idea was that this colliery was not a tightly knit conglomerate, as is usually the case, but rather a diffuse structure held together by belts, by roads.

BB: The atmospheric element was important. On top of that, we were in a hurry. We thought that if we photographed our way through the whole plant, it would take years. Then we made the film in two or three days.

HB: The thought was to drive through this very extensive industrial estate, to show the connections among preparation plant, winding tower, power plant and cokery. But as it turned out, there was so little movement there that the only movement in the film was provided by the camera.

UEZ: Because the colliery was already shut down?

HB: No. Strictly speaking, if you look at a mine like this, the only thing that moves is the wheel of the winding tower. I was thinking at the time of the early Charlie Chaplin films, where the camera sits on the tripod and everything else moves in front of it. Or Hitchcock’s film Rope, which takes place in one room.

UEZ: How strange that you give us these examples, as in fact you didn’t let the camera stay still.

HB: But panning the camera, up and down, right and left–that was no good.

UEZ: When did this experiment take place?

BB: 1973-74.

UEZ: Did you destroy the film in the end?

BB: No.

UEZ: We’re talking about a black-and-white film?

BB: No, it was in color.

That’s from an interview the Bechers did with Ulf Erdmann Ziegler in 2000. It was originally published in Art in America in 2002.

The Hannover Coal Mine was one of ten mining sites the Bechers photographed as early as 1966, but with a concentration in 1971-74, and presented in an “un-Becheresque” way: by site, not by typology. The Van Abbemuseum acquired one portfolio, 85 prints of the Hannibal Mine in Bochum, in 1976, but most of the hundreds of images from each site were unpublished negatives.

And at the time of the interview, the SK-Stiftung in Cologne [which houses the couple’s portfolio archive], began working to process and print images. They did a show, which traveled to the Huis Marseille in the Netherlands. And a catalogue, Zeche Hannibal (Coal Mine Hannibal), which sounds rather interesting.

Hannover Mine 1/2/5, Bochum-Hordel, Ruhr Region, Germany, 1973, Bernd & Hilla Becher [via moma]

As it happens, 200 of over 600 photos the Bechers made at Hannover have just been published in their own book. Zeche Hannover (Hannover Coal Mine) came out in Germany in July.

And it looks like MoMA acquired a selection of the Bechers’ mine landscapes in 2008. When seen together, they end up forming a higher-level series, a typology, not of structure, but of site. So they’re looking more Becheresque all the time. I’d still like to see that film, though.

Who Will Write The History Of The Pasadena Art Museum?

It’s funny how I think I know the history of the Pasadena Art Museum, when all I’m doing is projecting back and assuming a bunch of stuff based on a bunch of great-sounding anecdotes:

First museum shows for Duchamp, Lichtenstein, Warhol; Walter Hopps and the ur-Pop Art show; great posters [Ruscha, Duchamp, Warhol]; Pasadena Brillo Boxes; Serra’s massive 1970 fir tree installation; the increasingly intrafamily-related theft of Norton Simon’s nephew’s Warhols; Lichtenstein signing his Pasadena billboard.

First museum shows for Duchamp, Lichtenstein, Warhol; Walter Hopps and the ur-Pop Art show; great posters [Ruscha, Duchamp, Warhol]; Pasadena Brillo Boxes; Serra’s massive 1970 fir tree installation; the increasingly intrafamily-related theft of Norton Simon’s nephew’s Warhols; Lichtenstein signing his Pasadena billboard.

But then I read through Paul Cummings’ 1975 AAA interview with John Coplans, artist, Artforum co-founder & editor, and former Pasadena curator and director, and it sounds like the place was a total shitshow:

ladies’ auxiliaries overruling curators to keep buying local artists’ crap; architects calling the fire department on curators for hanging shows; firemen ripping lights and cords off of Rauschenbergs; trustees scheduling Warhol shows with Castellis behind their curators’ and directors’ backs; trustees not putting up a dime, or asking their friends to donate; trustees demanding shows that include work they own who then sell that work without notice a few weeks before the opening; and people freaking the hell out when some crazy East Coast guy with a Jewfro drops a dozen fir trees in their precious museum and calls it art.

And on and on. There are definitely some additional sides to the stories I’d love to hear: trustee/collector Robert Rowan, for one. He’s the guy who was apparently running the show during the late 60s, and who plotted the Warhol show with Castelli. And whose Temple of Apollo painting was featured so prominently on Lichtenstein’s billboard.

Also, Norton Simon, who apparently refused to lend all kinds of stuff as a trustee, but who obviously made a deal at some point, otherwise it’d still be called the Pasadena Art Museum.

Hopps, of course. Irving Blum, who drove around LA with a bottle rack in his trunk, waiting to get Duchamp to sign it. Even though a lot of folks have died, there are still plenty who are alive and perhaps willing to talk.

UPDATE: Well this sounds like a start. Tyler points to Susan Muchnic’s 1998 biography Odd Man In: Norton Simon and the Pursuit of Culture, which apparently “comes alive” with accounts of “the bizarrely bitter politics of Los Angeles museums.”

I Rumori Dell’Arte

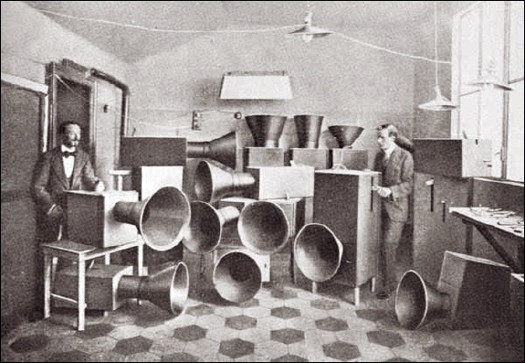

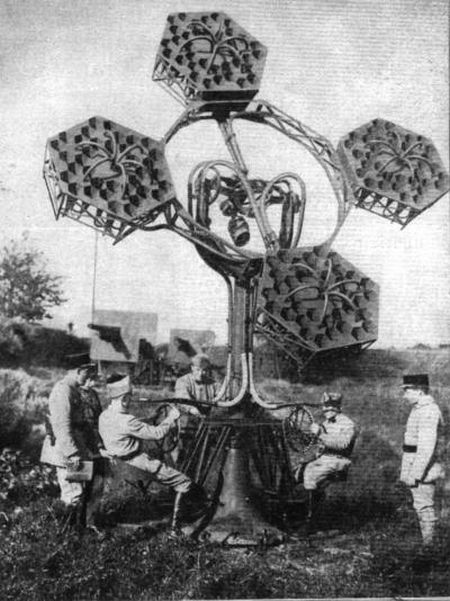

That’s Futurist painter Luigi Russolo on the left being helped by his friend Ugo Piatti, probably around 1913 or 1914. They stand amidst Russolo’s musical instruments, intonarumori, noise-intoners, which were designed in accordance with the principles laid out in Russolo’s Futurist music manifesto, l’Arte dei Rumori, The Art of Noise.

Though the trajectory of his ideas and influence is not quite as clear as The Hydra’s otherwise excellent recounting of his legacy imputes, Russolo was an innovator and visionary in the use of noise, found sound, in musical composition.

In The Art of Noise, Russolo makes a bold, lucid argument for music of the future to adopt the sounds of the world, especially the sounds of the machine, which had irrevocably changed the world’s aural landscape:

Ancient life was all silence. In the nineteenth century, with the invention of the machine, Noise was born. Today, Noise triumphs and reigns supreme over the sensibility of men. For many centuries life went by in silence, or at most in muted tones. The strongest noises which interrupted this silence were not intense or prolonged or varied. If we overlook such exceptional movements as earthquakes, hurricanes, storms, avalanches and waterfalls, nature is silent.

…

In the pounding atmosphere of great cities as well as in the formerly silent countryside, machines create today such a large number of varied noises that pure sound with its littleness and its monotony, now fails to arouse any emotion.

Then there’s this, the source noise for his Intonarumori, the sounds of the modern world:

the gurglings of water, air and gas inside metallic pipes, the rumblings and rattlings of engines breathing with obvious animal spirits, the rising and falling of pistons, the stridency of mechanical saws, teh loud jumping of trolleys on their rails, the snapping of whips, the whipping of flags. We will have fun imagining our orchestration of department stores’ sliding doors, the hubbub of the crowds, the different roars of railroad stations, iron foundries, textile mills, printing houses, power plants and subways. And we must not forget the very new noises of Modern Warfare.

Indeed. Russolo’s first public demonstration of Intonarumori was in Modena in April 1913. An instrument called the scoppiatore variously called the exploder or crackler, it replicated the sound of an internal combustion engine, not, actual explosions. That would be the detonatore, which came soon after.

I realize that it was not mentioned specifically in Russolo’s list of noises, but how can you not think of hail cannon when you see that photo up there? Russolo was born in 1885 in the formerly silent countryside of the Veneto, which was at the heart of the hail cannon boom [sorry] at the turn of the century. Thousands of hail cannon were installed across the region in 1901-02; in 1904, the Veneto was the site of the first official scientific study of hail cannon’s effectiveness. [They failed, and once-enthusiastic farmers turned against them en masse and sold their hail cannon for scrap.]

Did Luigi perhaps recall a pastoral orchestra of hail cannonfire from his youth when he wrote his manifesto? I have no idea, but it’s interesting to think about. None of the intonarumori recordings on Ubu sound like the modern hail cannon these guys try to throw their Barack Obama basketballs into.

On an object note, Russolo’s original Intonarumori were destroyed or scrapped, but his nephew Bruno Boccato has refabricated some following his uncle’s original plans. I think these are they.

Oh, And Hail Cannon. Must. Remake. The Hail Cannon.

Good grief, it was only a couple of hours ago, and I can’t even remember what took me to this three-year-old link roundup on BLDGBLOG that mentions hail cannons. I mean, hail cannon.

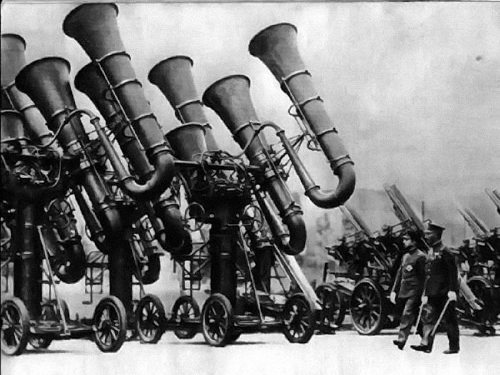

Turns out they still make’em, they just don’t make’em like they used to. It’s something that the Wikipedia entry on hail cannon calls them “pseudoscientific” devices. Because whatever scientific data exists for them now–and it’s not at all clear that there is much/any–it’s pretty obvious that hail cannon are technotheoretical holdovers from the turn of the 20th century.

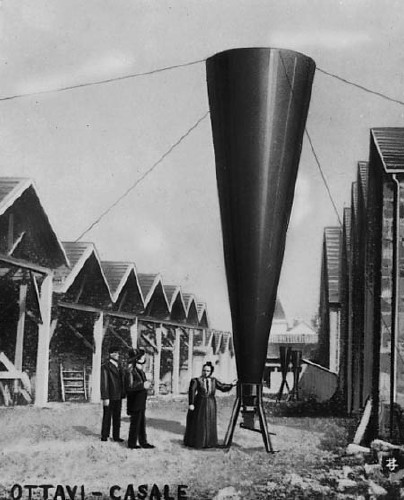

The promise of vintners being able to their crops by creating and channeling explosive shockwaves to pulverize hail in the hyperlocal atmosphere had been shooting around Europe since at least the days of Benvenuto Cellini, the Mannerist goldsmith & sculptor who claimed to have stopped the rain and hail with artillery fire.

Between 1896 and 1899, Austrian inventor Albert Stiger tested his design for a giant, megaphone-shaped mortar cannon that fired a smoke ring 300 meters into the air–and spared his village fields from hail damage. The Italians seized upon the hail shooting technology with incredible fervor, and within a year, there were 10,000 hail cannon protecting the vineyards of Northern Italy.

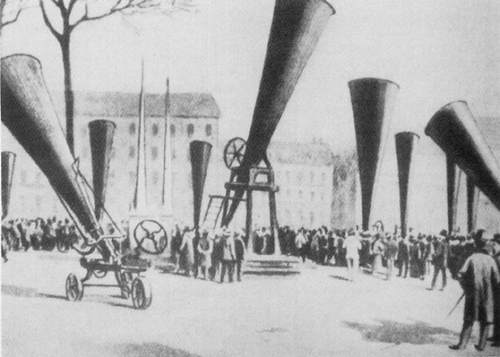

The first two International Congresses on Hail Shooting were held in Italy [Casale in 1899, and Padua in 1900], by which point at least 60 different models of hail cannon were on the market. So far, though, neither event was as extensively documented as the Troisième Congres international de defense contre la grêle, [the Third International Congress on Hail Shooting,] held in Lyon in 1901 [below, via]

For three days, the streets, parks, and plazas of the cities were filled with hail cannon. Were there live demos scheduled? Did people lay out picnics [well, it was Novembre] and listen to the big finish of the 1812 Overture over and over? Did the vineyards of Europe, laid out with a grid of hail cannon–an anti-Lightning Field–echo with rhythmic explosions during the most vulnerable months of the growing season? [Did I suddenly start speculating as if were auditioning for the guestblogging slot at BLDGBLOG?]

Eh, if they did, it didn’t last. Governments and scientists began questioning the data behind hail shooting, and by the time the Fourth conference rolled around in Graz, Austria, hail cannon salesmen were prohibited from attending. Suddenly sober and facing the facts–that hail shooting couldn’t be demonstrated to actually have any effect–the European hail cannon industry all but disappeared by 1905.

And so it is that refilling our cities’ public spaces with several orchestrasful of hail cannon would be a powerful, performative tribute to man’s indomitable urge to control the weather using military technology.

Q: Why is this Romanian Wikipedia page on Hail Cannon so darn good? [ro.wikipedia.org]

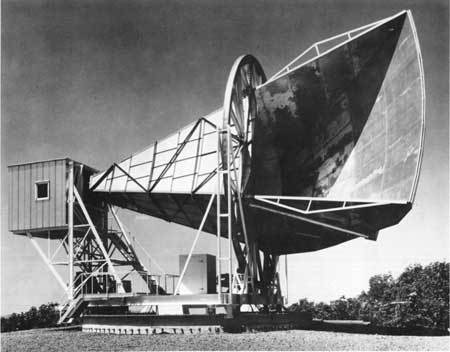

Must. Remake. Acoustic Mirrors & Locators

My list of incredible objects and machines from the past that need to be refabricated as art objects continues to grow.

Actually, I guess the acoustic mirrors, built in the 1920s and early 30s as part of a sound ranging air defense network along the British coast, still exist, most spectacularly at Dungeness, above. So there’s really no need to rebuild them, only to preserve then. And admire them for their undeniable Serrawesomeness and Kapooriosity.

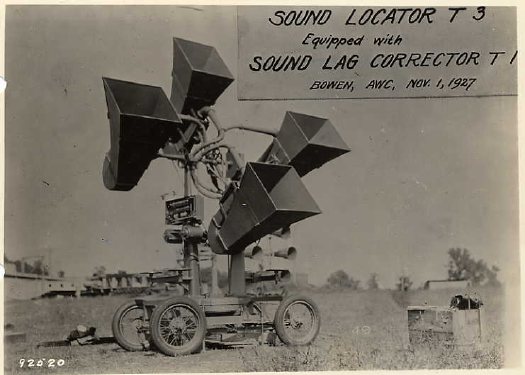

With the acoustic locators, however, the real question is where to start? Because, holy smokes, Dr. Seuss was basically a combat photographer.

Do I go with the first one I saw, a US Signal Corps Exponential Sound Locator T-3 from 1927? Which looks an awful lot like the one Frank House patented in 1929, which was assigned to Sperry Gyroscope, the US’ leading manufacturer of anti-aircraft sound locators? Yet which was developed beginning in 1924 at Fort Monroe, VA? And which, even when its breakthrough “ear” designs appeared in the popular press in 1931, was still compared to “antiquated phonograph horns”?

Or maybe go for decorative superlatives, such as the Hector Guimardian rarity of the télésitemètre designed by French Nobelist Jean-Baptiste Perrin? [via]

Or perhaps begin with a bit of the absurd, thanks to the Czech Mickey Mouse thing going on here? [via]

Frankly, the Japanese War Tuba is a little too Seussian Steampunk for even me to take it seriously, no offense to the emperor there. [via]

Surfing up information on these things, I’m well aware that I’m late to the sound locator game. But I didn’t think I was so far behind the Maker Faire/Burning Man crowd. Hmm. And hmmm.

Oh what the hell, maybe just throw this one on Governors Island and be done with it? The stethoscope to the stars.

But then there’s this highly portable German model–the awesome wheels and lowslung platform are typical among acoustic locators–which, wow. Stick your head in.

It’s like a real world precursor to other man-media interface devices, such as Walter Pichler’s Portable Living Room and Joep van Lieshout’s various fiberglass helmets, including the Orgone Helmet and the Sensory Deprivation Helmet [below].

Of course, it’s also a pretty short trip to a beer hat, so you gotta be careful.

Also of course, as a friend predicted when I started my giddy sound locator rant, it IS all about the satelloons. Specifically, the 50-foot horn-shaped radio antenna which Bell Labs used in Holmdel, New Jersey to track the epically faint radio signals reflected off of Echo IA’s mylar surface.

And which was later crucial to the inadvertent discovery of microwave background radiation, the first evidence of the Big Bang.

Earlier this morning, I tweeted half-seriously about the Bechers not working their way into The Original Copy, MoMA’s show about photography of sculpture. For all their conceptual sophistication, and their typological aestheticization to the industrial forms and structures they photographed, I don’t believe the Bechers saw their work in terms of, say, a readymade. Their art is their photos, not their subjects.

With their built-in obsolescence and anachronism, none of these objects could function as they originally did. Or were intended to do. And they don’t, really, remain as artifacts [except, as in the sound mirrors’ case, when they do]. So the only context in which they could plausibly exist–or credibly, since it’s plausible that they could be recreated by an enthusiast, a WWI re-enactor, or a nerded out…who is that guy in that refabricated sound locator, anyway?–is as an art object. And that’s the whole point, because they are these fantastic objects that surpass the presence and sophistication and beauty and…aura of so much intentional art, that it almost feels wrong not to appropriate or recontextualize or readymake them in somehow.

LATER THAT DAY UPDATE: Never mind. Going into my boxes, I see that, in fact, the title of the Bechers’ first book is Anonyme Skulpturen. Should’ve gotten the English edition after all. Stay tuned.

Yeah, well, in this 2000 interview with the Bechers, they talk about the beginnings of their work, which was considered “inartistic” by the art world of the day, the early 1960s. Bernd Becher: “To say, ‘This winding tower is an object, and it is just as interesting on its own terms’–that was not possible.” And then he talked about the urgency of photographing buildings they “didn’t like” which were slated for demolition, and explained not like them in terms of them not having “an aura.” So really, really, never mind.

Keeping Up With The Laurens

Good grief, The Hilfigers? Is anyone else old enough to remember the ads launching Tommy Hilfiger in the 80s? Just full page text:

Ralph Lauren

Calvin Klein

Perry Ellis

Tommy Hilfiger

Glad to see he’s returning to his desperate, striving, unoriginal roots.

Cretto Street View

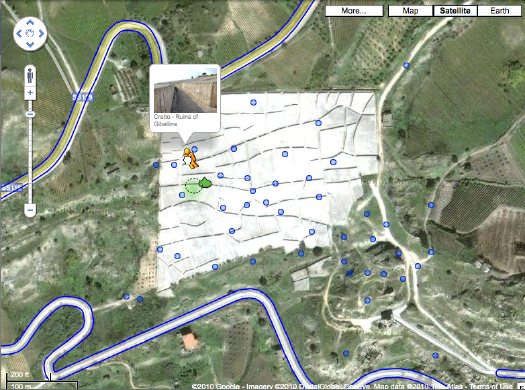

Christopher Knight took the occasion of an Alberto Burri retrospective in Santa Monica to tweet about Cretto, the artist’s absolutely incredible 20-acre memorial/earthwork, in which the earthquake ruins of the Sicilian town of Gibellina were encased in a grid of concrete. I’d mentioned Cretto in 2006, including a basic Google Map image.

Well, Street View has come to Gibellina. At some point, I suspect no one will marvel at the idea of using your laptop to drive around the backroads of Sicily, or to dive into geotagged photos of remote land artworks. But that point is not yet. The Street View images in particular have a great, desaturated feel that makes me imagine I’m right there for the ribboncutting. The future and the past is now.

Cretto, Alberto Burri/Ruins of Gibellina [google maps]

Related: finding Double Negative has never been easier

‘We Who Change The World’

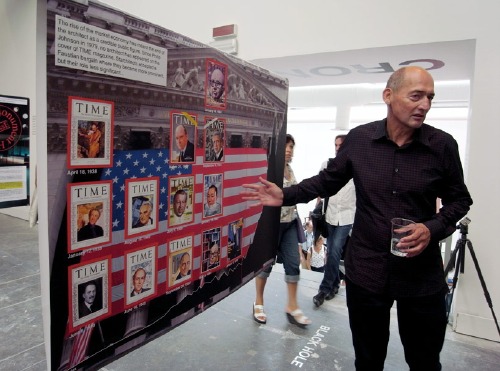

“My cover would go right here.” [image via]

Just like the Wallace Sayre quip about academic politics being so vicious because the stakes are so low, maybe the hubris and self-regard are so extraordinary because it’s the Venice Architecture Biennale. Anyway, let’s call it out quickly, and then look at what Rem Koolhaas has to say about modernism and preservation, because there may be some interesting things there.

[The text, by the way, is Designboom’s exhaustive 4-part guided tour (II, III, IV, pending) of “Chronocaos,” the OMA/AMO installation of research and history-related projects within Kazuyo Sejima’s exhibition.]

So. Hubris. Well, for starters, there’s the introductory wall text, which, wow:

Architects–we who change the world–have been oblivious or hostile to the manifestations of preservation the past. Since 1981, in Portoghesi’s “Presence of the Past,” there has been almost no attention paid to preservation in successive architecture Biennales.

I mean, I’m sure the visitors to the exhibition just ate that up, but should I even be reading it, much less commenting on it? Not being either an architect OR one who changes the world and all?

Then there’s the photo above, and its associated text:

The rise of the market economy has meant the end of the architect as a credible public figure.

Since Philip Johnson in 1979, no architect has appeared on the cover of TIME magazine.

Starchitects accepted a faustian bargain where they became more prominent, but their role less significant …

We’ll get to that public/market economy stuff in a minute; first let’s look at this Cover of TIME [CoTIME] business, which is as alluring as it is non-credible. [I was about to say “useless,” but really, it’s quite useful; it just illustrates something other than what I think Koolhaas intends.]

As it happens, Jonathan Franzen’s CoTIME this week gave Craig Ferhman the chance to do a similar CoTIME analysis for writers:

Time put 14 authors on its cover in the 1920s, 23 in the 1930s, seven in the 1940s, 11 in the 1950s, 10 in the 1960s, eight in the 1970s, four in the 1980s, four in the 1990s, one in the 2000s, and, now, Franzen in 2010.

Ferhman finds that behind the cover, TIME’s profiles of writers are truncated, shallow, reductivist, or otherwise nearly empty of actual content. He cites multiple examples of writers resisting the–what else to call it?– “faustian bargain” of a CoTIME, which was long considered uncritical, low-brow, and hypey. The cover becomes a thing in [and of] itself, a distillation of the magazine’s–and by direct extension, its owner’s–desire to assert authority and control over a cultural agenda.

In this light, and given the close tracking between architects’ and writers’ presence on the cover, one might be led to wonder if it’s not architecture [or literature] which has changed in the last 20-30 years, but TIME and its own role or strategy as a megaphone for culture. Or to question the suitability for a democratic society of monolithic, top-down annointing of public figures’ credibility. That one would not be Rem Koolhaas, though.

In any case, CoTIME reveals as little about the reported “end of the architect as a public figure” as it does about the ego-driven architect’s desire to, well, to appear on the cover of TIME.

And yet. You know, this is right where I was going to acknowledge and explore OMA/AMO’s more salient points, about how, as Designboom puts it,

…this year represents the perfect friction point between two directions: the world’s ambition to rescue larger and larger territories of the planet, and the global rage to eliminate the evidence of the post-war period of architecture as a social project. both tendencies–preservation and destruction–are seen to slowly destroy any sense of a linear evolution of time.

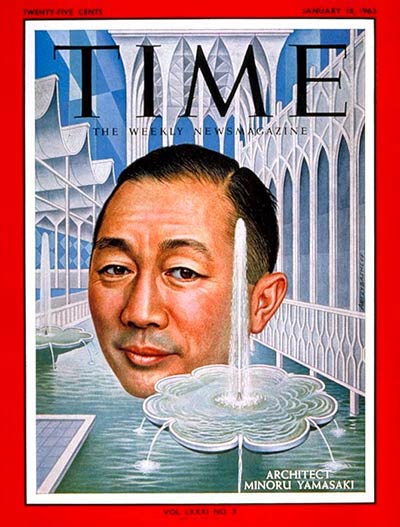

But I think I’ll take those up later. Because I just clicked through to see the CoTIME of the architect I thought would be the least likely candidate for a credible public figure in his day: a January 1963 story on Minoru Yamasaki.

1963. Which turned out to be pegged to his recent selection to design a 15-acre site for the Port Authority in downtown Manhattan:

What form the project may be taking in Yamasaki’s inventive mind is his secret, but simple arithmetic shows that the vast space needs and limited site could force him to record heights or bulk. One thing the center will not be is harsh or cold. In taking the road to Xanadu, Yamasaki has turned office buildings, schools, churches and banks into gentle pleasure palaces that are marvelously generous in spirit. He shuns monuments. He is suspicious even of masterpieces, which he feels often better serve the ego of their creators than the well-being of those who use them. He may have committed some architectural heresies, but if he has, it is largely because he is a humanist with enormously appealing aspirations. He wants his buildings to be more than imposing settings for assorted clusters of humanity; they should also recall to man the “gentility of men.” should inspire “man to live a humanitarian, inquisitive, progressive life, beautifully and happily.” However the Trade Center turns out, it will have that ideal– and it will be built with the ultimate degree of loving care.

It’s hard or impolitic to remember how reviled Yamasaki’s buildings were as architecture and as part of the city. But I don’t think anyone would dare argue about the World Trade Center that it was their architect who changed the world.

Keep Calm, Arts, And Carry On

Here [via COS] is David Shrigley’s animated short for Save The Arts, which is trying to help arts organizations in the UK avoid debilitating budget cuts.

At first, I thought WTF?? The Arts are so screwed! Then I thought, well, maybe they should’ve just gotten Nizlopi to do it. And then I thought for the whole “think of the children!” angle to work, it’d be nice if the kid–who HAS the arts right now, mind you–wasn’t an inert loser with less than three lines to string together. And then I saw, in my related videos selection, and I mellowed the heck right out.

Because Shrigley being Shrigley had previously saved Pringle of Scotland from being shuttered. Not only did he save Pringle, he helped get all the other jumpermakers bombed back to the sockmaking age.

And what did he save Pringle to do, you ask? Why, to commission Ryan McGinley to film Tilda Swinton’s exploration of the moody Highlands in Pringle eveningwear for the Spring/Summer 2010 collection:

And then it all came together when I saw the credit: Creative Director – Neville Wakefield, the great roving-so-as-not-to-have-to-give-up-too-many-side-gigs curator at PS1. I think the Arts will be just fine.

update: And a good thing, too, because Shrigley’s right: Tracy Emin’s not going to come put out your housefire. [via @bhoggard]

Take Ivy That

Ah, September 10th, an inadvertently trenchant date for unloading on the trendchasers’ seemingly complete lack of historical self-awareness.

And I’m not talking about that perfect, frivolous Marc Jacobs afterparty on that nearly perfect late summer evening which only acquired its poignancy the next morning when, well.

I just found this incredible wool twill authentic made in USA Ivy prep revival classic trad artisanal manly tweed outdoor ruling class WASP vintage Woolrich shirt jacket, which I’m rocking right now because it’s kind of chilly typing with the windows open.

See, I’d gone up to Connecticut Berkshires Brimfield North Adams Darien New Haven over the weekend. But since I had the car, I also stopped in Long Island City at our storage unit. And pulled a bunch of stuff out of a cedar-filled sweater suitcase I’d packed in 1995. I do believe it was vintage when I bought it in 1989.

It starts to feel like freakin’ Groundhog Day around here sometimes, but fortunately, I’m ready.

last year: authenticity vs. realness