Caught this on the CBC last night. I always assumed a kilogram is equal to the mass of a liter of water. But it turns out to be messy/tricky/complicated to measure water accurately enough, plus, some scientists decided to change the definition soon after it was decreed, so a kilogram is actually equal to the mass of the kilogram, the International Prototype Kilogram, or IPK, also known in France as Le Grand K. It’s the only unit of measure, says Wikipedia, “that is still defined in relation to an artifact rather than to a fundamental physical property that can be reproduced in different laboratories.”

The IPK is made of a platinum alloy known as “Pt‑10Ir”, which is 90% platinum and 10% iridium (by mass) and is machined into a right-circular cylinder (height = diameter) of 39.17 mm to minimize its surface area. The addition of 10% iridium improved upon the all-platinum Kilogram of the Archives [originally made and adopted in 1799. -ed.] by greatly increasing hardness while still retaining platinum’s many virtues: extreme resistance to oxidation, extremely high density, satisfactory electrical and thermal conductivities, and low magnetic susceptibility. The IPK and its six sister copies are stored at the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM) in an environmentally monitored safe in the lower vault located in the basement of the BIPM’s Chateau de Breteuil in Sèvres on the outskirts of Paris. Three independently controlled keys are required to open the vault. Official copies of the IPK were made available to other nations to serve as their national standards. These are compared to the IPK roughly every 50 years.

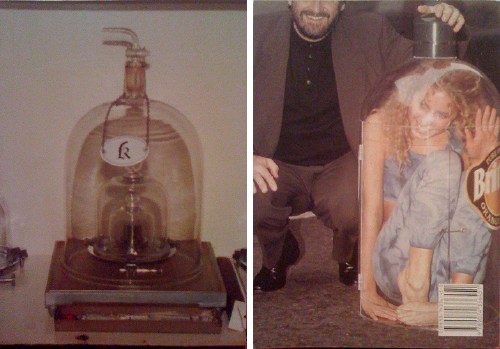

The IPK is stored under three bell jars, and its six sister copies are each stored under two.

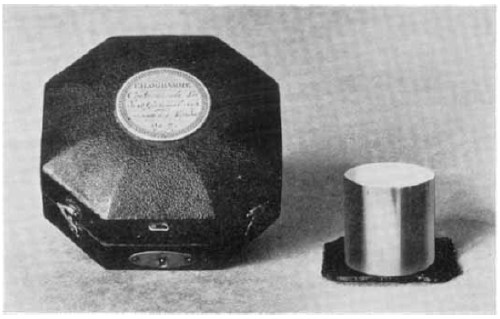

The IPK and two other cylinders were manufactured in 1879 by Johnson Matthey, assayers and refiners for the Bank of England. [IPK is the third, KIII.] Johnson Matthey made 40 replicas in 1884, which were calibrated to IPK. 34 were distributed in 1889 to signatories of the Meter Convention for use as national standards. Two of this original batch, K4 and K20, are in the US. K20 was designated the US standard prototype in 1889.

The process and protocols for comparing these replicas to IPK, known as “periodic verification,” have evolved over the years. The BIPM was apparently not so distracted between 1939 and 1946 that they couldn’t develop “The BIPM Cleaning Method,” which involves a chamois, ether, ethanol, and steam cleaning with bi-distilled water. [Considering the Metric system itself was implemented in the midst of the French Revolution, and proceeded even as key scientists were being guillotined, I guess it’s not so surprising.] Models have developed to describe the rate of surface contamination.

What has become clear after the third periodic verification performed between 1988 and 1992 is that masses of the entire worldwide ensemble of prototypes have been slowly but inexorably diverging from each other. It is also clear that the mass of the IPK lost perhaps 50 µg over the last century, and possibly significantly more, in comparison to its official copies.

Given this variation and divergence, much of which cannot be explained, the CIPM [Committee &c.] in 2005 recommended redefining the kilogram as a constant of nature. So far, a suitably stable, reproducible constant has eluded metrologists.

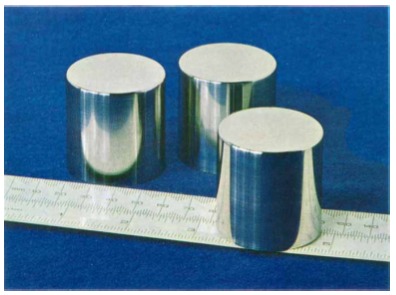

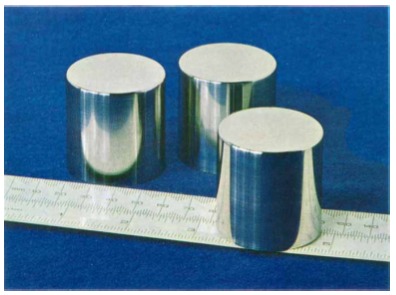

One method is to define the number of carbon-12 atoms in a 1kg cube. Another, part of the Avogadro Project, is to create a single-crystal sphere of silicon, then measure the sphere radius and its internal crystal lattice with interferometry, and then polish it with single atomic level-accuracy to reach 1 kg. A sample is presented here with rather dramatic flair by a master optician at the Australian Centre for Precision Optics:

Its appearance might look familiar to regular readers of this website.

The human attempt to account for the world through exacting science results in a minimalist object that transcends other Minimalist objects, all while inhabiting a conceptual framework that transcends Conceptualist frameworks.

And I want some. And when I get my kilogram[s], I’ll put them on the shelf next to my satelloons and my photos of the entire universe from the Palomar Sky Survey.

Kilogram, Grave [wikipedia]

photos of the International Prototype Kilogram [bipm.org]

“The kilogram and measurements of mass and force,” Journal of Research of the National Institute of Standards and Technology, Jan-Feb, 2001 [findarticles.com, PDF original at nist.gov]