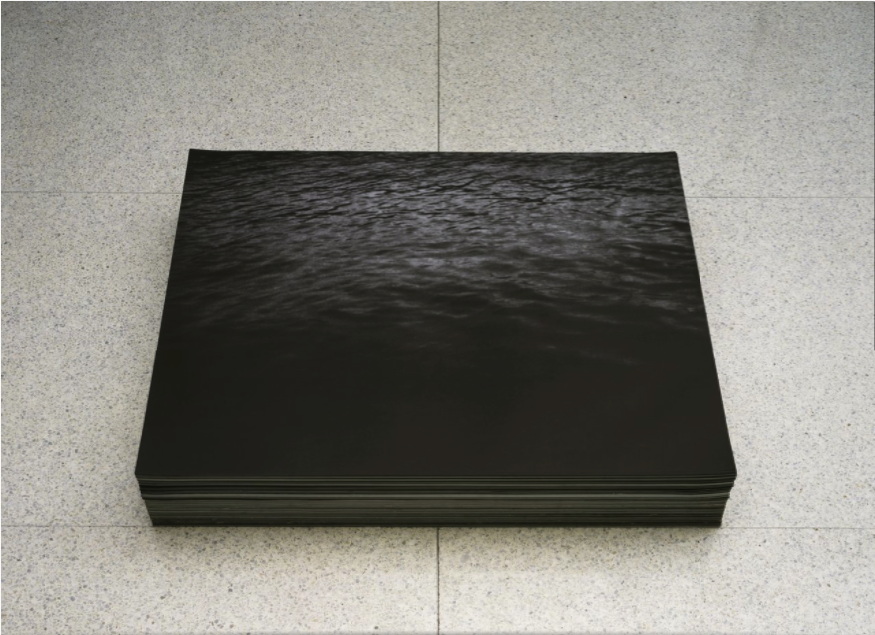

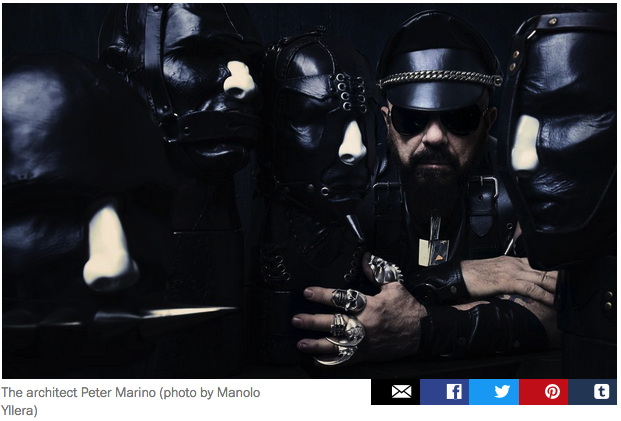

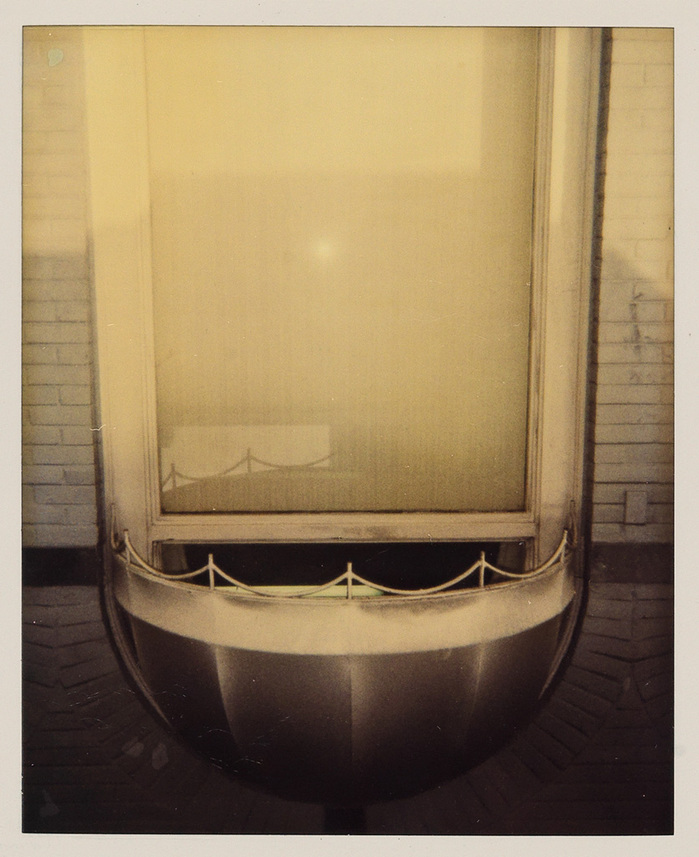

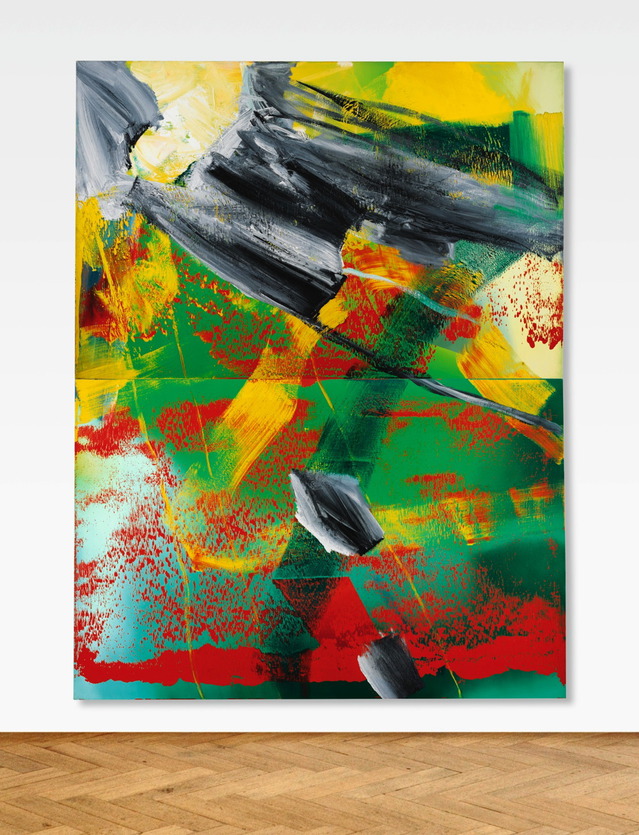

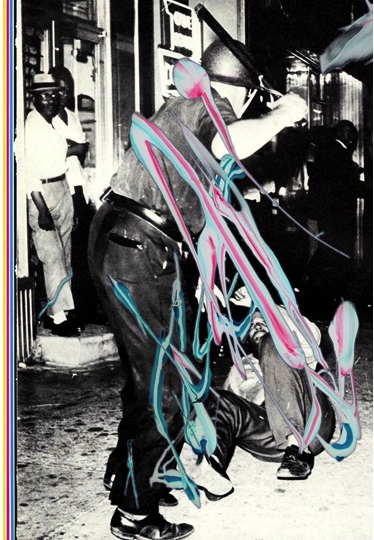

Top: screencap from “Putain d’epoque”, with people standing in mylar ponchos. Bottom: Ghost, 2007, molds of kneeling family members made of aluminum foil, installed at Saatchi in 2009. via

Kader Attia has filed a plagiarism lawsuit against French rappers Dosseh and Nekfeu over visual similarities between the music video for “Putain d’epoque” and Attia’s 2007 installation Ghost. I’m a non-expert in French intellectual property law, so I can’t say whether the visual echo legally outweighs the differences in material, execution, setting, content, and concept. [Attia discussed the genesis of Ghost in AiA in 2009.] But I know mylar when I see it, and when I don’t. The works are utterly different, even though there is a one-second dronecam shot in the video that shows the men kneeling face down, as if in prayer. Is that really what this is about? Because it does not feel like plagiarism. The effect is apparently that the just-released song is stripped from the video while it’s being litigated.

via

Attia’s complaint is based on artists’ rights, and the resistance to “non-consensual use” of artists’ work: “Everyone is plundering us, whether it’s advertising or the cultural industry.”

That quote comes from Kendell Geers, who wrote an open letter to Attia defending quoting and plagiarism and the freedom all artists rely on to use and interpret the world around them as they make their work.

Since 1988 I have developed a body of work and a language around the very subject of plagiarism, taking my cue from Lautréamont, the French poet born in Uruguay, who said “Plagiarism is necessary. Progress implies it. It holds tight an author’s phrase, uses his expressions, eliminates a false idea, and replaces it with just the right idea.” His revolutionary text Poésies was the Holy Water that baptised the Surrealists, a text written between the lines of words plagiarised from other authors. I have always wondered if Paul Gauguin was inspired by Lautréamont when he said that “Art is either plagiarism or revolution,” but there can be no doubt who inspired Guy Debord when he wrote his revolutionary book the “Society of the Spectacle” in 1967. He said that “Ideas improve. The meaning of words participates in the improvement. Plagiarism is necessary. Progress implies it. It embraces an author’s phrase, makes use of his expressions, erases a false idea, and replaces it with the right idea.”

Well played, Guy.

Geers calls for all artists and “every human being who believes in changing the present for a better future” to defend artists’ freedom to express themselves, and especially for artists with power and presence in the marketplace to defend those without. As Powhida tweeted about Geers’ statement, “It’s amazing. Collectively we have to stand up for individualism. This is the hardest thing in this star fucked market.”

As I always say, I replace melancholy by courage, doubt by certainty, despair by hope, malice by good, complaints by duty, scepticism by faith, sophisms by cool equanimity and pride by modesty.

Or maybe I should say it again this way: ‘Poetry is for everyone.’ Poetry is a place and it is free to all cut up Rimbaud and you are in Rimbaud’s place.

Un clip de Dosseh et Nekfeu accusé de plagiat par l’artiste Kader Attia [lemonde.fr]

Putain d’époque ! Lettre ouverte de Kendell Geers à Kader Attia à propos de son action en justice pour plagiat contre Dosseh et Nekfeu [lemonde.fr via @frieze]