When we last considered the techno-militartistic merits of pre-WWII era sound location devices, I wondered where to start. And now I know: the Netherlands.

When we last considered the techno-militartistic merits of pre-WWII era sound location devices, I wondered where to start. And now I know: the Netherlands.

I’m not sure why, but it was acoustic locator-palooza over there. On the wall of the awesome library in Stroom, the visual arts center in The Hague, I spotted a large poster of a guy sitting in a German-style portable locator. And there were two more images in Stroom’s recently published journal, Podium for Observation

Turns out they’re from the Museum Waalsdorp, which is located on a military base outside of The Hague. And apparently, they’re not German-style at all; they were designed in Waalsdorp in 1927 by an engineer named Ir.van Soest. And they have some there. But it’s only open on Wednesdays, and only with advance reservations.

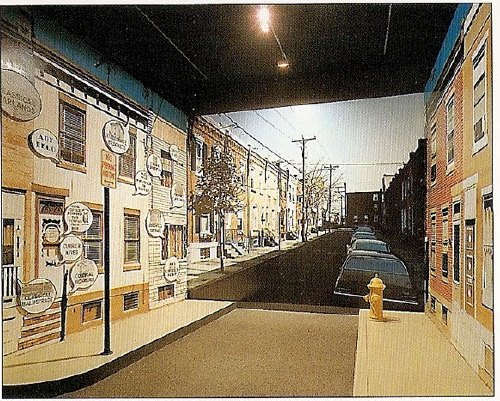

In Amsterdam on Museumnacht, meanwhile, we headed from the Stedelijk to ARCAM, the city’s architecture center & museum, because their current exhibit, “Music.Space.Arch.,” sounded like I could have curated it myself. Or blogged it, more like:

The focus of the exhibition is the suggestion of space as created with the aid of acoustic objects. The spatial experiences relate to various scales, ranging from the intimacy of the individual to the spacious openness of the urban space.

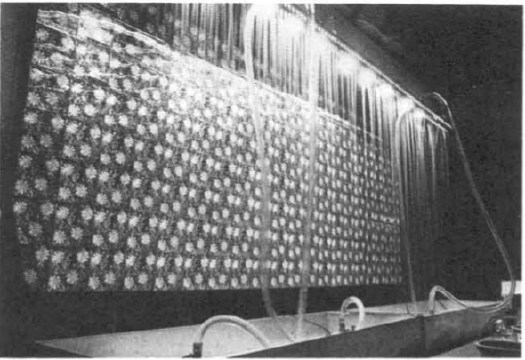

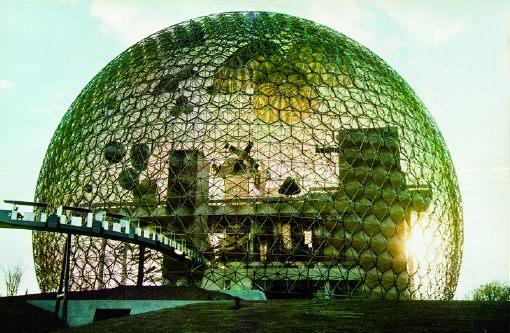

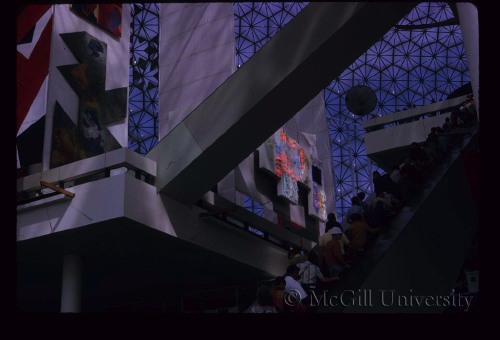

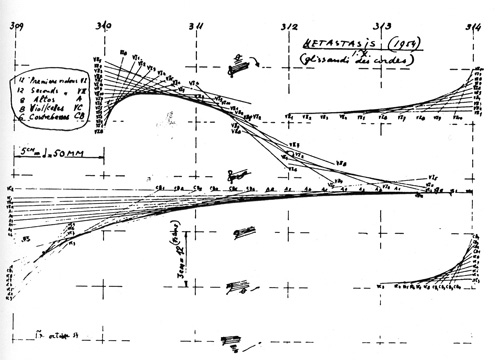

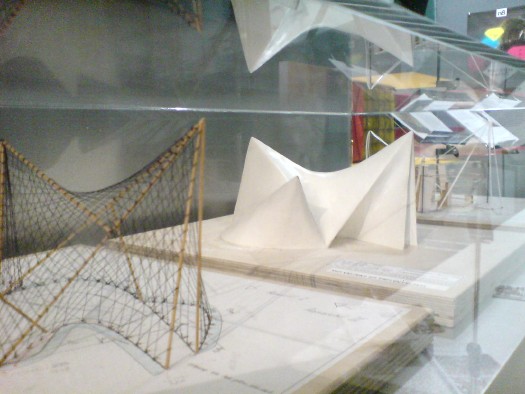

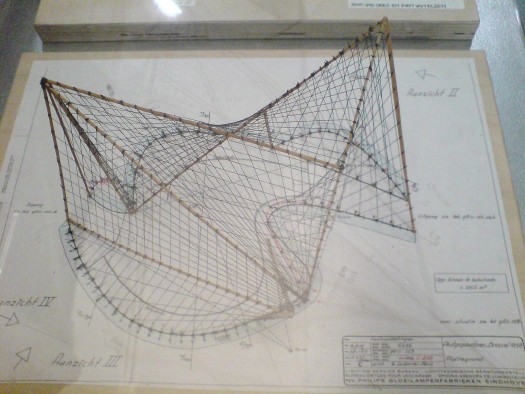

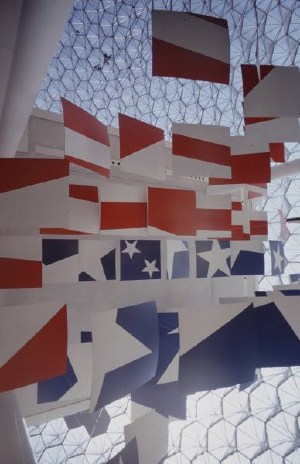

Included among the collected objects are the ‘Side Scan Sonar’, which brings the urban space surrounding ARCAM to the visitor, and listening equipment with which enemy aircraft were detected in the Second World War. With ‘Sound Scrape Shoes’ by Ricardo Huisman, the ARCAM building becomes the source of the experience, while in the presentation of the famous Philips Pavilion of 1958, the proportions are completely different from what we are familiar with.

Acoustic locators AND a re-creation of the Philips Pavilion? How could we miss?

Well.

We literally arrived at ARCAM one minute after the tap dancer had begun her show. Now for me, tap dancing is to real dancing what rhythmic gymnastics is to real gymnastics, or what synchronized swimming is to swimming: an over-aestheticized mutation that is somehow unaware of its own awfulness. And that’s on a good day.

When you have a Dutch punk tap dancer–an alternative tap dancer, in a country where they probably have a Bureau of Alternative–in tasseled pants, dancing in the dark while an assistant shines a flashlight on her shoes, whose “intimate interaction” with ARCAM’s building basically meant pushing the entire contents of the exhibit into the corner so she could erect her hollow tap floor, it is really unforgivable and unsalvageable. And that’s even before the audience participation segment began.

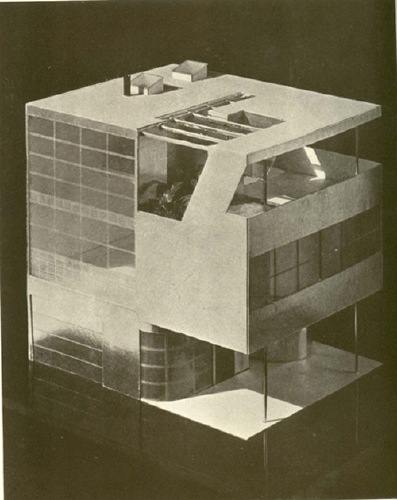

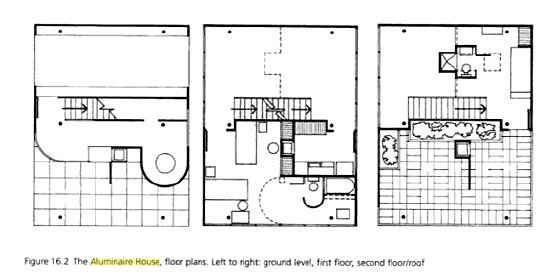

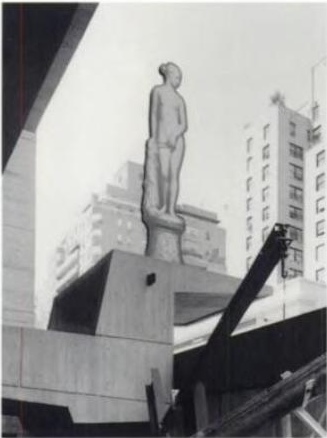

So we stayed in the corner, where the “completely different” proportions of the Philips Pavilion re-creation turned out to mean three A2-size models borrowed from the Atomium. Fantastic, but tiny. That wireframe’s especially nice.

But the projection on the exterior of the museum of Le Corbusier, Xenakis, and Varese’s Poeme Electronique, considered to be the first immersive multimedia environmental installation, had been turned off, another casualty of the evening.

Oh, and there on a pedestal, behind some people’s butts and under their coats, was a real live Van Soelst acoustic locator. Only it wasn’t from Museum Waalsdorp; it was from somewhere else entirely: the Wings of Liberation Museum in Best. Holland must be the most acoustically located country in the world right now.

And so as we left behind a slightly chaotic-seeming jumble of awesome objects brought together by an amorphous, subjective theory, I realized that the only way to tell this blog apart from a multi-million-euro art, architecture & cinema center is that I’m the one without a tap dancer.

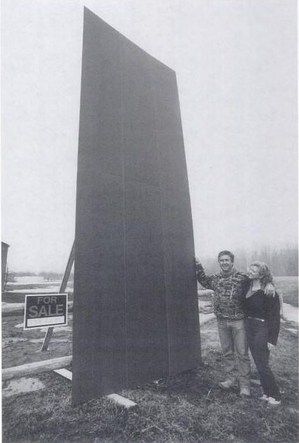

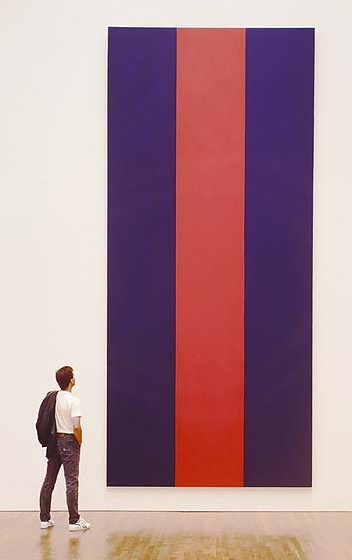

When it was publicly announced in March 1990 that the National Gallery of Canada had purchased Barnett Newman’s 1967 painting,

When it was publicly announced in March 1990 that the National Gallery of Canada had purchased Barnett Newman’s 1967 painting,

Du Duve then considers at great length how Mr. Czupryniak’s pricing scheme deftly maps out the incongruities between artist and painter, value and worth, elites and the public, boss and laborer, exploiter and exploited. Every dollar between $401 and $1.8 million, he writes, accrues to Newman’s status as an artist as perceived by the cultural elites–and as extracted by them for their own aesthetic pleasure from the unappreciative public [the Taxpayers] who got stuck with the tab.

Du Duve then considers at great length how Mr. Czupryniak’s pricing scheme deftly maps out the incongruities between artist and painter, value and worth, elites and the public, boss and laborer, exploiter and exploited. Every dollar between $401 and $1.8 million, he writes, accrues to Newman’s status as an artist as perceived by the cultural elites–and as extracted by them for their own aesthetic pleasure from the unappreciative public [the Taxpayers] who got stuck with the tab. Speaking of National Gallery of Canada upheavals, Walrus Magazine, late-career post-minimalist kitsch, and Blake Gopnik:

Speaking of National Gallery of Canada upheavals, Walrus Magazine, late-career post-minimalist kitsch, and Blake Gopnik: