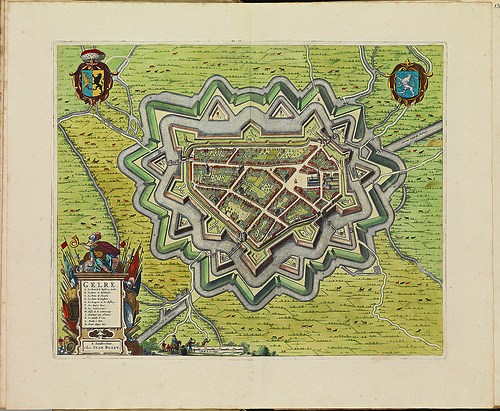

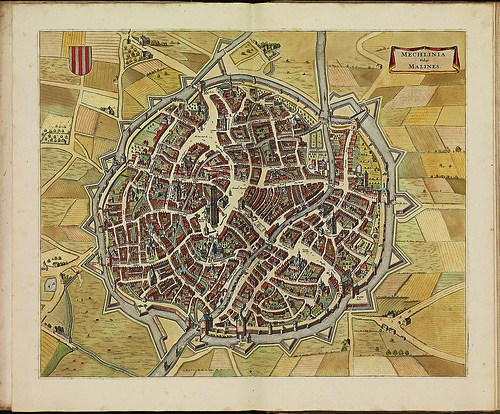

This just in from the greg.org Department of Stunningly Beautiful Digitized Maps of The Netherlands:

Bibliodyssey has some highlights from the National Library of the Netherlands’ fresh upload one of the rarest and most beautiful atlases in history, mid-17th century Dutch cartographer Frederik de Wit’s Stedenboek, or Book of Cities.

Who knew that the Dutch had such a long, rich, aesthetically awesome history of defense-related polygonal alterations of the urban landscape?

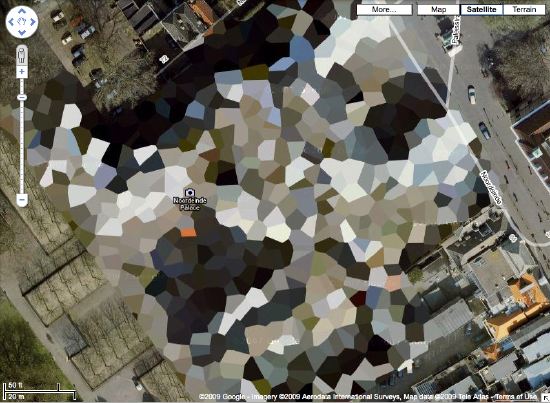

At least maybe now we have some idea where that crazy camo blob in Nordwijk came from:

Stedenboek [kb.nl]

Dutch City Atlas [bibliodyssey]

Author: greg

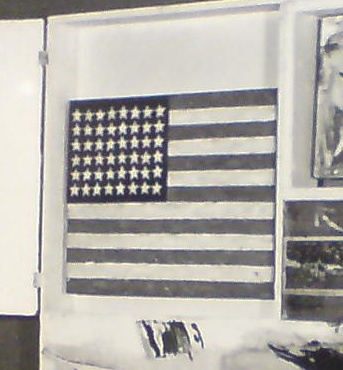

‘Loss of Painting – American Flag – Jasper Johns’

So here is where, after a few months of searching, I basically get caught up to the editors of Johns’ collected writings, who noted in 1996 that Johns’ Flag painting disappeared from Leo Castelli’s warehouse sometime “before June 8, 1965.”

After a couple of days of digging through the newly opened Castelli Gallery archives at the Archives of American Art, I found that date on the gallery’s insurance claim reporting the “Loss of Painting – American Flag by Jasper Johns valued at $5000 $12,000.” [the higher figure is written in by hand.]

The insurance company’s memo acknowledging the claim said that “Mr. Mellors is to meet with the assured on Wednesday afternoon regarding the details of the claim.”

June 8th was a Tuesday, and sure enough after his visit, Mr. Mellors had more to add. A follow-up memo is titled more clearly, “Theft of Painting – 6/6/65 – “Desk Explosion 65″ by Lichtenstein.” Mr. Mellors, it said, “…when discussing the loss on “American Flag” by Jasper Johns was informed of the above loss by Mr. Castelli.”

So what we have now is not just a “before June 8,” and a “loss” [although that is still the word used in relation to the Johns], but a date: “June 6” and a “theft.” And not just one work, but two.

The only other documentation I could find is a small note, “Call headquarters for 9th Precinct,” “Warehouses/ 75 Cliff St/ 25 First Ave” and the name [?] “Kay Kaz.”

The 9th Precinct is the East Village, which makes me think it was the First Avenue location. Kay Kaz, I have no idea, and I can’t find anything online so far. But this was not Leo’s handwriting, so I am assuming someone was taking this information down on the phone.

Frankly, I can’t tell if I’m more Law & Order: Art Victims Unit or Columbo, but this is feeling very real to me, trying to piece together what happened, where, when, and with whom, just using a few old memos.

The 6th was a Sunday, so it seems as if someone made a weekend visit to the warehouse, found the Johns missing from Short Circuit, called the police, then called the gallery to give instructions about following up with the police. And then on Tuesday, they filed a claim for the Johns, while seeing if anything else was missing. And by Wednesday, they found a Lichtenstein gone, too.

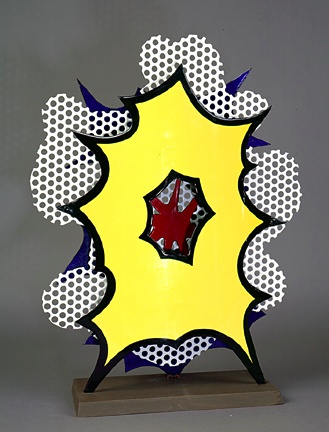

As it turns out, both works are similarly sized: small and portable. The Johns Flag is 13 1/4 x 17 1/4 inches, and Desk Explosion is 20 x 16 x 4–wait, 4-in? It’s a sculpture. An enamel-painted metal freestanding sculpture on a 4-inch deep base, made in an edition of 6:

Small….Explosion (Desk….Explosion), 1964, : image via lichtensteinfoundation.org

Either way, maybe tracking the Johns is now a matter of tracking the Lichtenstein.

So what do we know now? First, that the AAA’s Castelli Archive is awesome. I could blog those boxes out for days if the photo restrictions were a little more conducive. Instead, I find them more illustrative of the way that art historical information is still transmitted: in relatively hermetic dribs and drabs.

My previous assumption that the Johns may not have been “stolen” stolen because it was never reported as such turns out to have been wrong. Well, those reports existedtl, anyway, even if the Johns wasn’t exactly described as “stolen.” [I was also wrong about a couple of other assumptions and speculations I made in earlier posts, which I’ll get to separately and soon.] But generally, the information I’m finding does appear to have been found by at least someone, sometime, before. So I wonder what I’m doing: if all these curators and scholars have already been over this before, am I just playing art detective for my own belated educational amusement?

But questions still arise that keep me on the hook:

- Where’d those precise dimensions come from? Castelli? Rauschenberg? Johns himself? Someone had them on hand at the time the police were notified. I guess that answers the question about whether the Flag was an autonomous work?

- Why were Rauschenberg or Short Circuit not mentioned at all in the insurance claim?

- And the claim–and a half dozen 8×10 glossies of Rudy Burckhardt’s original photograph of Short Circuit was in Castelli’s Johns file, not his Rauschenberg file? [Just end it with an uptone and it becomes a question.]

- And what was Short Circuit even doing in Castelli’s warehouse? Wasn’t it in Rauschenberg’s own collection his whole life? In which case, why wasn’t he filing insurance claims on it?

- What IS up with that Lichtenstein?

- Rudy Burckhardt?

- And obviously, who is Kay Kaz, and what’s s/he doing in the middle of the memo about the polce?

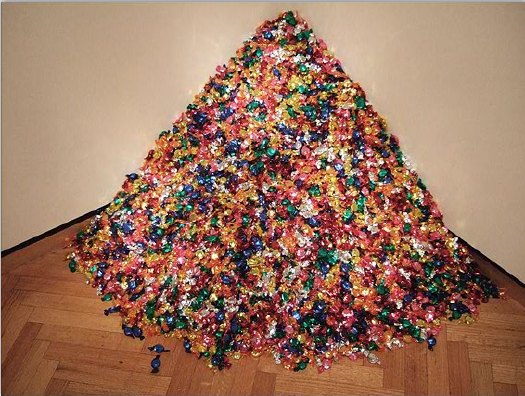

Untitled (Portrait of Ross in LA)

Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), 1991

RB Before I knew you I saw something… You know what I’m going to say?

FGT I dedicated a piece to Ross.

RB Exactly. I thought, this is so sweet, I want to meet him. He dedicated this thing to me and I don’t even know him. (laughter) It put me in the best mood. And then someone said to me, “You idiot, why would he dedicate something to you? It’s his boyfriend.”

-Ross Bleckner interviewing Felix Gonzalez-Torres in the Spring 1995 issue of Bomb Magazine. This is about as funny as Ross gets. He really is as foolish as Felix is thoughtful. Well worth a read.

Bonus: did you know that by Fall 1994, after five solo shows and with his retrospective set to open at the Guggenheim, Felix had never had a review in the New York Times? [I just checked, and the closest was a paragraph in a cranky 1990 survey of Minimalist revival by Roberta Smith. She called his stacks “almost laughable.”]

Matrix Or Minecraft?

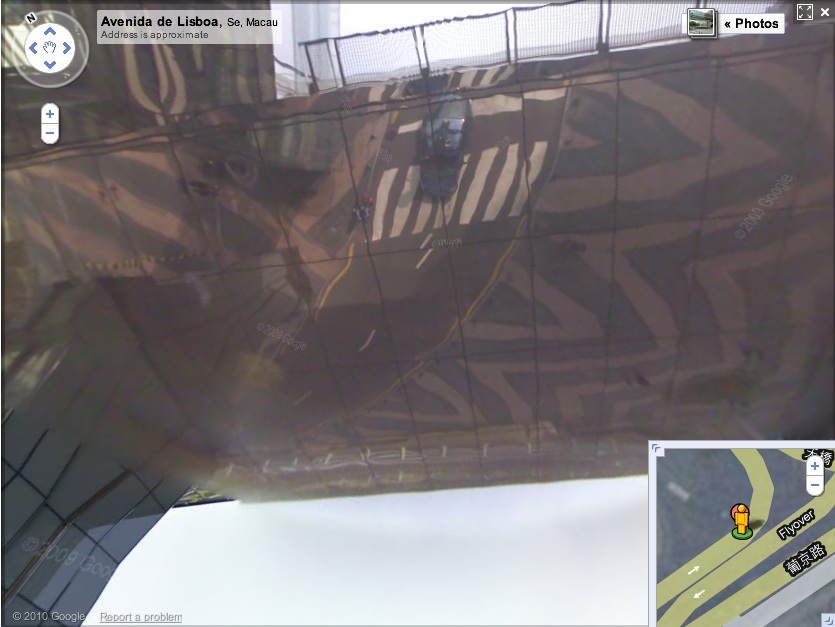

Via one of my Senior Street View Scouts John comes this eerie shot from Simple Ranger’s Street View essay of Macau. [Here’s the live link.]

Seriously, is that building real? Even if I wander over to look at it up close, my doubts only increase.

And frankly, looking up at the sky and seeing the Google Street View car reflected in the curved, mirrored underside of the Grand Lisboa Casino’s elevated pedestrian walkway is not helping.

Bondeno Street View

Compared to Germany’s digital scrim effect, the Italian Google Street View opt-out regime is extraordinarily, even romantically, naturalistic.

Haha, no. It’s a photo from Elmar Haardt’s careful and unassuming project documenting Bondeno, a seemingly unremarkable small town in Ferrara. [via the incomparable mrs deane]

Zombie Mark Cross Now Stalks The Earth

Reading through the press release for the new upscale family travel site Poshbrood.com, I was surprised and promptly filled with dread by the chance to win a “faboo Mark Cross saddlebag.”

Because that means someone has brought the luxury brand back from the dead because, what, zombies are really on trend right now? Because if you have any concept of venerable or luxury or heritage or leather or gift or anything when you hear the name Mark Cross, it has literally nothing to do with anything actually happening or made this millennium. And that residual brand goodwill embedded in your brain is now the intellectual property of a roving band of scavenging garmentos and opportunistic luggage salesmen.

Which, God bless’em, credit where it’s due, but also blame, awful, tacky blame.

The Four Color Process Manifesto

One of the first Japanese sayings I learned was “Chiri mo tsumoreba, yama to naru,” “Pile up dust and it becomes a mountain.”

At his incredible blog Four Color Process, John Hilgart continues to mine the gap between comic book art and comic book printing. Looking back over his year’s collection of images, often tiny details pulled from the seemingly insignificant corners and backgrounds of old comic book frames, he’s come up with an excellent and expansive essay. He doesn’t, but I’ll call it the 4CP Manifesto:

Gone are the page, the frame, the plot, and localized contextual meaning. What remain are the color process and what are generally called the “details” of comic book art. These are the two lowest items on the totem pole of comic book value – poor reproduction and the least important, most static elements of the art itself. Our proposition is that these elements are important and aesthetically compelling.

Who is responsible for this art? At the level of a square inch of printed comic book, no one was the creative lead. 4CP highlights the work of arbitrary collectives that merged art and commerce, intent and accident, human and machine. A proper credit for each image would include the scriptwriter, the penciller, the inker, the color designer, the paper buyer, the print production supervisor, and the serial number of the press. Credit is due to all of them, to differing and unknowable degrees, for every square inch of every old comic.

[image: Gotham Dawn, via 4CP]

In Defense of Dots: the lost art of comic books [4cp.posterous.com, thanks city of sound for the heads up]

Previously: Four Colour Process [greg.org]

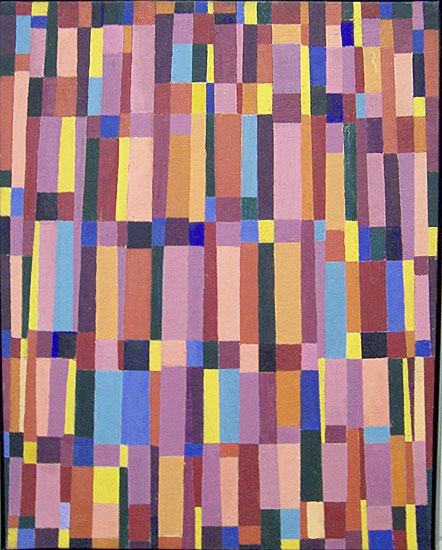

What I Looked In 2007 & Again Just Now: Myron Stout

Doug Ashford ended the 2009 presentation I just posted about, “Abstraction as the onset of the real,” with a slide of this beautiful painting, Untitled, 1950 (May 20) by Myron Stout.

Washburn Gallery had a sweet little early Stout show in 2007, which I’d completely forgotten about. Back when he was still writing about art, NY Times chief art critic Michael Kimmelman reviewed the show:

…his mentor remained Hans Hofmann, who helped him see how to construct a purely abstract picture, while his great inspiration was Mondrian, about whom Stout observed that “the tangible and sensational world was still the raw material for the universality which he would create for himself.” In other words, Mondrian, like Stout, remained firmly connected to nature and the real world.

Things that happened in 2007 can seem so long ago and far away. I need to hustle up some Stouts to look at, pronto.

‘Art Directly Builds Who We Are – It Engenders Us’

I’m still trying to figure out quite what he said, but whatever it is, Doug Ashford said the hell out of it. Forget speaking or writing like this, I wish I could even think like this. Brains back on, people! Vacation’s over!

Over all, our efforts in the Democracy project were to try to see how democracy happens at the site of representation itself, not just where information is transferred or built, but rather at the very place we recognize ourselves in performing images, where we have the sense we that we are ourselves, feel a stability that is hailed and recognized by others. A radical representational moment, whether collective or not, is one that suggests we can give ourselves over to a new vision through feeling, an experience linked to contemplation and epiphany. In this way no public description of another, in frame or in detail, can be presented as politically neutral. So when Group Material asked, “How is culture made and who is it for?”, we were asking for something greater than simply a larger piece of the art world’s real estate. We were asking for the relationships to change between those who depict the world and those who consume it, and demonstrating that the context for this change would question more than just the museum: a contestation of all contexts for public life. In making exhibitions and public projects that sought to transform the instrumentality of representational politics, invoking questions about democracy itself, Group Material presented a belief that art directly builds who we are – it engenders us.

From Doug Ashford’s “Group Material: Abstraction as the Onset of the Real,” an adapted paper presented in 2009 at the “New Productivisms” conference at Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, as published online by the european institute for progressive cultural policies [eipcp.net via @mattermorph via @joygarnett]

‘On Kawara’s Last Piece!’

Maybe it was the news, or those long family car rides over Christmas with his cousin’s evangelical radio station going the whole way. But Frank Wick has of late been considering The Big Questions of Life, questions such as, “When The Rapture comes, will On Kawara have enough time that day to finish his painting?”

I guess the answer has been there all along in Kawara’s audio piece, Kawara’s Four Thousand and Four Years, B.C. and Two Thousand and Eleven Years, A.D.. He that hath ears, let him hear.

What I Looked At Six Months Ago: Douglas Coupland’s Roots Paintings

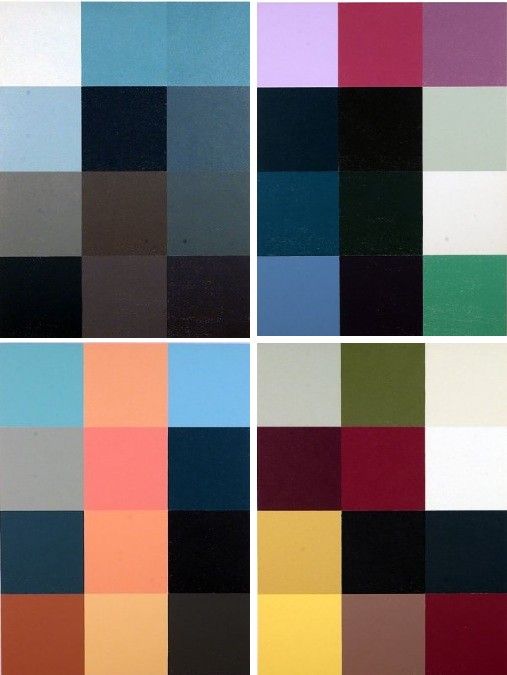

Holy smokes, it’s been 15 months since I found the Dutch Camo Landscapes on Google Maps; just over a year since I started systematically screengrabbing them; a little less than a year since Google’s particularly beautiful Delaunay triangulation distortion was replaced by a more typical pixelation algorithm; and about the same time since I last posted one of the “What I Looked At” installments, where I tried to figure out how to approach painting these things by studying the techniques of other hybrid, found, hard-edge, geometric digital, photographic, reductivist, surveillant, abstract, or Dutch Landscapes. Folks from Albert Cuyp and Picabia to Arthur Dove and Sheeler to Mondrian to Sherrie Levine [below].

The longer I take to think about how to paint without actually trying to paint, the more I keep accumulating and questioning potentially resonant work. And I wonder: what would it mean to consciously appropriate someone else’s technique? if I taped my edges, would there be more of a connection to Odili Donald Odita? If I made little polygonal stencils and squeegeed, would it be too Brillo? Is there an implication in the kind of precise painterly edges of Mondrian as opposed to the surprisingly tentative edges of Sheeler, or the just-fill-it-in forms of Dove? Should I skip the paint, and just blow those bad boys up and print the hell out of’em on the biggest canvas/paper I can find?

It [basically, obviously] boils down to some ongoing uncertainty or doubt or skepticism or insecurity or whatever over whether these things should exist. Emphasis on things and should. Does everyone who makes stuff feel that? It’s like Baldessari’s classic fortune cookie of a painting, “I will not make any more boring art,” but with the make in flux as much as the boring. I just remained unconvinced about the justification for these images as objects. [On the “bright” side, like the unshot film in the director’s mind, the unmade artwork does remain perfect–for me, anyway.]

Anyway, all this comes to the fore because last summer, I saw images of some polygonal abstracted landscape paintings by Douglas Coupland, which were part of, or inspiration for, or somehow connected to, the Fall/Winter clothing and home furnishings colabo he designed for the Canadian retailer Roots. They were exhibited and for sale in Coupland X Roots pop-up stores in Vancouver and Toronto.

There was zero info online, so last summer and fall, but I deduced that they were digital reductions of iconic paintings by the Group of Seven, the early 20th century landscape painters who rather self-consciously set out to create a national cultural and visual identity for Canada via its landscape. Coupland’s Roots collection was an extension of that national branding project, only he referenced the unifying forces of electrification, television, and moose logos.

At least that’s what I gleaned from the web and press releases. I tried in vain to get any information on the paintings from Roots, Coupland, or his galleries, but it was total radio silence. So I ignored them back. Only now, as I check back, do I find that “culture guru” Coupland has a show up of the paintings, through this week, at Monte Clark Gallery in Vancouver. Faux-encrypically titled G72K10, the paintings turn out to be exactly what I thought they were.

“Thomson (Sunset), 2010, Oil on canvas, 58 x 72 inches” image: monteclarkgallery.com

To a point. Because though the captions say things like “oil on canvas” and “acrylic and latex” and “unique pigment print” it is completely unclear whether the images on the dealer’s website are of the objects themselves or of their digital sources. Maybe it doesn’t matter to Coupland. Here’s how the gallery describes them:

By digitizing the likeness of specific works, Coupland has produced large-scale hard-edged paintings on canvas, presenting his own vision of the Group of Seven in 2010.

Doesn’t sound like he’d use something as retardataire as a paintbrush for a forward-looking project like that. Though it’s hard to tell from the jpg, the date on this unidentified type of limited edition print being auctioned next month by the Writers’ Trust looks earlier than 2010. Or not.

So while I still can’t decide if my painterly obsession is a vice, Coupland’s project is at least makes clear that materialist indifference in the pursuit of digitized aestheticism and conceptual slickness is no virtue.

Untitled, By The Pachinko Ginbasha Master Of Amakusa

A dismal, depressing subject can be made enjoyable by great writing. And the spirits can be lifted by an awesome photo at the end. These are my takeaways from Richard Hendy’s travel/history/economics/politics/apocalyptic decline essay on Amakusa, a hardscrabble group of islands near Kyushu, Japan.

Hendy’s blog Spike Japan documents the underside and overlooked, and Amakusa certainly sounds like it’s had the short end of the stick since forever, basically, and all they have to show for it is a 15-year-old, $120 million Bridge To Nowhere–designed by Renzo Piano.

But this incredible photo gives me hope. I’m transfixed by this pachinko sign. I mean, just look at those lines. The neonya-san who made that is literally drawing with light in space here. Is there a kanji-based, gestural tradition within the Japanese neon signmaking industry? Have Zen brushstrokes been translated or reperformed and fixed in 3D glass tubing? Or maybe it’s Action Painting, frozen in time and space instead of dropped onto the canvas in the barn in Springs?

Perhaps Peter Coffin’s 2004 sculpture, Untitled (Line after B. Nauman’s The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths) 1, isn’t abstract at all, but documentary. Perhaps the topic could be addressed by a panel discussion at a future symposium, after Amakusa’s calligraphic lighting sector has been revitalized, and the island has claimed its rightful place as the Japanese Marfa for the neon arts.

1 which, hello, is now in MoMA’s collection.

At The Movies With Mao Zedong

Tom Scocca posted about the story just before Christmas, but apparently, Mao Zedong was a Bruce Lee fan.

That’s how the Chinese press is reporting the story of Liu Qingtang, [刘庆棠], a ballet dancer and close ally of Mao’s wife Jiang Qing, who, as the deputy minister, was put in charge of films at the Ministry of Culture.

Mao was encouraged because of cataracts to cut down on his reading, and to switch to film. Liu was charged with programming and procuring prints for Mao’s private screenings.

Scocca picked the story up from Raymond Zhou in China Daily, but Liu’s account was first published in November in the Yangcheng Evening News, a major daily out of Guangzhou. It was posted online a few weeks later. Here’s the Chinese, “毛泽东有多迷李小龙?”, and a choppy Google translation, “Mao Was a Bruce Lee Fan?” [It’s remarkable how far Chinese-English autotranslation still has to go. We’re barely at Babelfish levels here.]

Liu says his story is from 1974:

Mao Zedong’s like to watch movies there are several categories: first, the international award-winning film; second film biography, “Abraham Lincoln”, “Napoleon,” he loves; third is like watching garden scenery film, like most British films. Often, Mao heard good movie, the file will be down to watch, watch movies right away, very happy.

. At some point, then, Liu traveled to Guangzhou, and on to Hong Kong, where he had not a little bit of trouble getting prints of Lee’s films, The Big Boss, Fist of Fury and The Way of the Dragon, from the wary movie mogul Sir Run Run Shaw.

Where Mao would watch only a few minutes at a time, taking up to ten days to finish another film, he apparently sat straight through Lee’s movies, and even demanded repeat viewings. Liu was afraid to send the prints back to HK, in case Mao asked to see them again.

The incorporation of Mao into the Bruce Lee fan club, the American-born, Hong Kong-raised, one-quarter German Lee [who is known by his given Cantonese name, Li Jun-fan (李振藩)] was timed with the premiere on CCTV6 of a documentary, “Legend of Bruce Lee,” which debuted at Beijing University. It all serves to retroactively position Lee as an inspiring, nationalistic hero of all Chinese, including the Mainland, where he was unknown during his lifetime.

And it all makes me wonder what was actually going on film-wise in the PRC during the tumultuous waning days of Mao’s rule. Because there are some contradictions and gaps in Liu’s story as it’s reported:

Wikipedia, which has the only actual date I can find so far, says Liu was installed as Deputy Culture Minister in February 1976.

Jonathan Clements’ 2006 biography of Mao dates the cataracts to 1974, but also says that Mao was nearly blind, and his slurred speech could only be decoded by his nurse.

As Reeve Wong pointed out to China Daily, Bruce Lee’s films were actually produced by Shaw’s rival studio, Golden Harvest. It’s not clear how or where, but Liu still insists that he got the prints from Shaw.

Given the difficulty in tracking down prints of Hong Kong’s most popular films, I have to wonder what “international award-winning films” and biopics Liu was able to get his hands on. I mean, was there a copy of John Ford’s 1939 film Young Mister Lincoln laying around a cinema after the Revolution?

And the big question, did he watch Michelangelo Antonioni’s epic 1972 documentary Chung Kuo? Antonioni originally shot Chung Kuo/ Cina as a left-to-left cultural gift, with Communist Party participation and supervision. After it came out, though, Madame Mao & her cinematic comrades denounced spectacularly as a capitalist reactionary insult to the Motherland.

A lengthy bio of Liu Qingtang at hudong.com says that in 1976 as the Gang of Four maneuvered for post-Mao power, Minister Liu personally oversaw the production of three “hit films,” Back [反击]、Grand Festival, [盛大的节日], and Fight [搏斗] which attacked Deng Xiaopeng.

After Deng regained and consolidated power and began undoing the effects of the Cultural Revolution, Liu followed the Gang of Four into public disgrace, trial and jail. But he’s apparently out now, and doing fine, if not quite keeping his dates and titles straight.

Toward A Cyclorama-Shaped Gettysburg Memorial To The Wounded

See, this is what I’m talking about. And by see, I mean look. Last Spring, while trying to save Richard Neutra’s Gettysburg Cyclorama building from destruction by the Park Service and misguided preservationists, I backed into the idea of adapting it as a wheelchair-accessible battlefield observation platform. [Observation platforms are the primary category of structure the Park Service exempts from its professed objective to “restore” the battlefield to its 1865 condition.]

A perfect complement to a disabled/wheelchair-accessible structure would be a memorial or exhibit for those soldiers wounded in battle. While honoring those who sacrifice so much for their country, such a tribute would also bring the issues of the disabled and the disfigured out from the shadows where they have been relegated for centuries, educating all visitors as to the truer human cost of war.

Fortunately, such an exhibit and the educational value it can provide have long been contemplated by folks like Mike Rhode and his colleagues in the archives of the National Museum of Health and Medicine, which boingboing points out began during the Civil War as the Army Medical Museum. Rhode posted a photoset of documentary photos, artifacts, and period documentation of Civil War casualties and medical treatments. The almost industrial scale of battlefield injuries and the largely forgotten threat of disease and infection spurred on major advances in treatment, surgery, amputation, prosthetics, and sterilization.

So check out Rhode’s flickr for a difficult-to-see example of what an important-to-see exhibit might look like.

And consider that if Neutra’s Gettysburg building were to hold such a memorial, it would begin to pay back some of the karma deficit modernist drum-shaped architecture incurred when the Army Medical Museum was torn down to make way for the Hirshhorn Museum.

Related, next, a year later, in fact: Gettysburg and the Disney/Ken Burns Effect

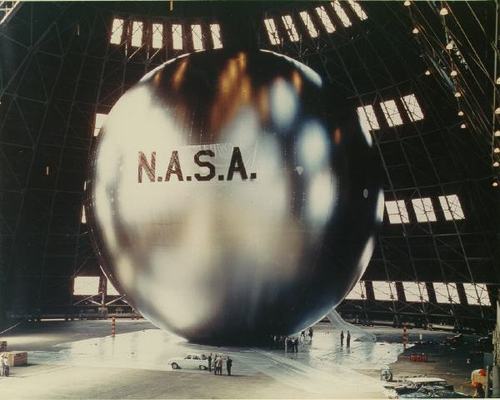

Deck The Halls With Satelloons

Via David at BoingBoing comes slow word that the world’s largest airship hangar is now a Malaysian conglomerate-owned water park. So says the Smithsonian’s Air & Space magazine.

The structure was built in 2000 on a repurposed military base south of Berlin in the former East Germany by Carl von Gablenz’ industrial airship startup, CargoLifter AG. It is 360 meters long, 210 meters wide, and 107 meters high, more than large enough to accommodate the firm’s proof-of-concept vehicle, the CL75 Air Crane.

The CL75 was built and tested in 2001. The 60-meter diameter spherical balloon was 60 meters in diameter. Also, it was 60 meters in diameter. That’s almost 200 feet, people. It’s almost as if someone heard about Project Echo’s 100-foot satelloon, and decided to double it [apologies to all the 7th graders in the audience, who know that doubling the diameter of a sphere more than doubles the volume. The point here is the pure optics of the number.]

But why a gratuitous reference to Project Echo, one wonders? Oh, maybe because the CL75’s airship was manufactured by TCOM, the former Westinghouse subsidiary which began in 1960 as an attempt to commercialize British WWII barrage balloons for aerial surveillance. And which, since 1996, has been housed in the disused USN airship hangar in Weeksville, NC. [“The TCOM Manufacturing and Flight Test Facility near Elizabeth City, NC has become the East Coast hub for all airship activity.”]

Which is the same disused USN airship hangar the original Project Echo team used to test inflate their first satelloon. Just check out the vented windows in the giant clamshell doors:

The CL75 was destroyed in a storm in 2002, the same year CargoLifter went bankrupt. But fortunately, the East Coast hub for all airship activity soldiers on.