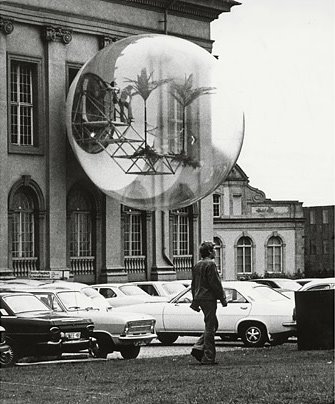

In 1972, the Austrian architecture collective Haus-Rucker installed Oasis Nr 7 at Documenta 5.

A steel pipe structure was cantilevered out the window of the Friedericianum, and a platform, two palm trees, and a hammock were installed. The entire thing was enclosed in an 8-meter translucent vinyl bubble.

Oasis 7 was re-created last September It was built on a fake Friedericianum facade at the Victoria & Albert Museum for the exhibition, “Cold War Modern: Design 1945-1970.

Haus-Rucker project archive [ortner.at]

Time lapse making of video: Oasis 7 in the Victoria & Albert Museum [iconeye.com]

via atelier, where I’ve been lifting all sorts of interesting things this week.

Category: architecture

77 Million Paintings On The Sydney Opera House, By Brian Eno

Composer Brian Eno is projecting some of the 77 million iterations of his 77 Million Paintings series onto the Sydney Opera House as part of the Luminous Festival.

The Festival, which Eno is also curating, consists of three weeks of performances, talks, and exhibitions. It runs through June 14.

I’m not a huge fan of Eno’s painting, necessarily, but it looks pretty fantastic in the photos that have hit flickr so far. I’ve got a short list of buildings which should have art projected on them, and I was wrong not to include Utzon’s opera house.

That said, once the infrastructure’s in place to project Eno’s work, it should be equally possible to project other artists’ works, too. I know he has 77 million works to get through, but maybe Eno could have curated someone besides himself into his big show?

Luminous Festival, curated by Brian Eno [sydneyoperahouse.com via city of sound]

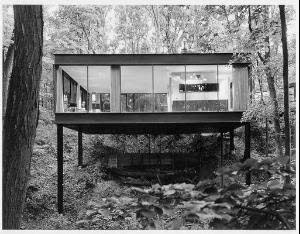

Bueller!!

OK, why did no one tell me when I posted about A. James Speyer’s awesome-but-maybe-never-realized Miesian Adirondack cabin that the Chicago architect was responsible for the most important Glass Box-in-a-Forest of the entire 1980s?

Of course, I’m talking about Cameron’s house in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, which just went on the market for $2.3 million. [realtor.com, or try cinematical when that one expires]

For Sale: Crazy Finnish Futuro House

Bring your architect! Uh, on second thought, you’d probably be better off bringing your boatwright.

Wright20 is auctioning off one of Finnish architect Matti Suuronen’s 1968 Futuro Houses on June 2.

After creating the first fiberglass and polyurethane modular structure as a ski cabin for a friend, Suuronen began producing and delivering Futuro Houses in 1969 Around 100 were built, maybe 60 survive, and up to 18 of them are supposedly in the US. There’s one on Hatteras in North Carolina. Another is used as the VIP room atop a strip club in Tampa.

Futuro expert Richard Pisani, who starred in a 2005 NY Times article about the Futuro revival, has a global registry going at futuro-house.net. What, was futurohouse.com taken? Yes, yes it was. And the competing saucer directory has tracked the current Wright20 house–last known location, Bailey, Colorado–from its 2002 sale on eBay to its 2006 return to the market.

No matter how awesome Suuronen and his design might be, it’s kind of a freakshow, and most of the Futuro House owners seem like weirdos for whom a Fuller-style geodesic dome home was just too conventional.

So whether you go by the architecture-as-collectible standard of a Prouve prefab, or the modernist real estate standard, a portable saucer house in need of a gut restoration is going to be a tough sell at $50,000-70,000.

Lot 138: Futuro House, Matti Suuronen, est $50-70,000 [wright20.com]

lots of Futuro House photos on flickr, including a family lounging in a vintage brochure and an abandoned saucer in Texas [flickr]

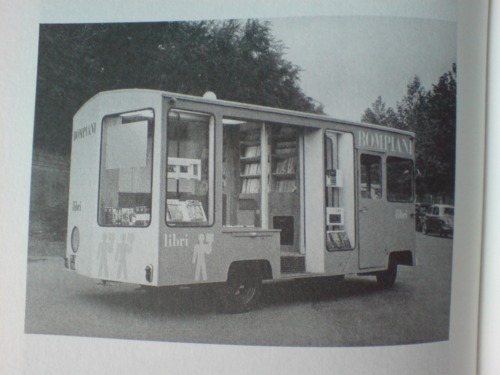

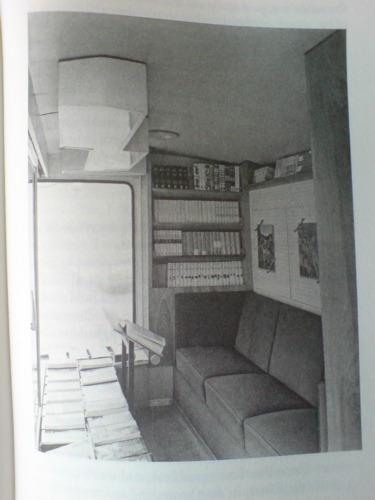

Bompiani Librimobile, 1955, by Enzo Mari

Hans Ulrich Obrist – Yes, I see here – there’s a vehicle, a truck, in the picture.

Enzo Mari – The editor [of Bompiani] had a problem, and we’re speaking about the fifties, in that he needed to transport retail books to remote places in the Italian provinces. These remote places were not as we know them today, as they didn’t even have bookstores. We had to create a truck that could be used as a small bookstore. Once it arrived in a small town, people could make use of it like a shop. The truck, from one point of view, presented itself as a bookstore with windows; inside there was a small parlor, a sofa, a small collection of books, where the merchant could receive and converse with the visitors.

images from [I think] Mari’s 2004 book, La Valigia senza manico, reproduced in Hans Ulrich Obrist & Enzo Mari: The Conversation Series – 15 [amazon]

Frederic Remington, Modernist?

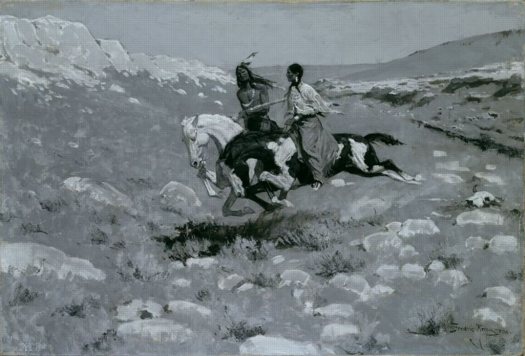

Frederic Remington, Ceremony of the Fastest Horse, c. 1900 [art institute of chicago]

Look, I’m as surprised as you are that I was stoked to see a Frederick Remington painting, but here we are.

As a card-carrying East Coast Art World Elitist, I’ve never given Remington’s work a second’s thought, not even an ironic revisionist, “Well, he’s alright, but he’s no Norman Rockwell!” Which is exactly where I placed him art historically, buried somewhere in Appendix B of Janson.

But we were at the State Department the other night, at a dinner held in the Diplomatic Reception Rooms, and a Remington painting was the freshest, most modern thing around.

When they opened in 1961, “The Rooms” looked like typical, International Style boardrooms of the period, which, oddly for a government agency housed in a 2 million-sf pile, the State Department thinks is a slam:

Then they were very much like the rest of this modern State Department building, with wall-to-wall carpeting on concrete floors, brown panelled [sic] walls such as those found in offices, and unattractive acoustical ceilings. The exterior walls of the entire eighth floor (where the Diplomatic Rooms are located) were floor-to-ceiling plate glass with explosed [sic] steel beams.

In 1969, Nixon’s newly appointed ambassador to Britain, Walter Annenberg, initiated a vast, classical makeover, replacing the steel and glass with 18th- and early 19th century-style woodwork and antique furnishings.

They’re a spectacle–the bathrooms are absurdly fantastic–but complete artifice. [Though all the artifacts are real enough. It was incredible to see the Treaty of Paris just sitting there on the desk.] Many wall texts in The Rooms and on most pages of the DRR’s website –which was also apparently last remodeled in 1969–are relentlessly dismissive of modernism:

Once paneled in brown plywood, with oppressively low ceilings and wall-to-wall carpeting on concrete, the hall is now a handsome space with thirteen-foot high ceilings and a Tabriz rug on a mahogany floor.

It’s amazing, because the building’s lobby, which is all chrome and glossy black stone and linoleum, with a giant, glass-enclosed garden and phalanxes of security desks, gives off a nearly pitch-perfect aura of cool, postwar power. And The Rooms’ balcony has round skylights in the overhang, and reads like an amped up homage to the terrace for the Member’s Lounge in Goodwin & Stone’s original MoMA building.

Edward Durrell Stone had finished 2 Columbus Circle in 1964 [even abandoned, the top floor’s superluxe mahogany paneling, travertine, and bronze made me want to have our wedding party there], and he was working on the Kennedy Center nearby, which would open in 1971. And in 1960, Eero Saarinen was finishing his US Embassy in London, and in 1962, his soaring terminal at Dulles opened–named after Eisenhower’s Secretary of State, no less! True, looking back, Establishment Modernism of the late 60’s doesn’t pack the punch of the heyday works a decade earlier, but it should’ve been good enough for government work, right? And yet in 1969, modernism apparently had no one able to challenge Annenberg’s transformation of America’s seat of diplomatic power into the American Wing at the Met.

But anyway, back to the Remington. Unsurprisingly, it’s not on The Rooms’ website, and I didn’t take a photo or even note the title. But it was a landscape, of the West somewhere, with some guys on some horses, crossing some river, all not important. What struck me was that it was painted in black and white. Or more precisely, it was painted in a fascinating, dynamic range of grays. It was too painterly to be a Mark Tansey, but it could have been an early Gerhard Richter.

I had no idea Remington often painted in monochrome, but when you realize why he did, it makes total sense. It’s not that he was painting from photographs, although he often did, and the 19th century paintings’ resemblance to 20th century photographs is striking; what’s awesome was that Remington was painting to photographs. He was usually making images on assignment for Harper’s Weekly or some other weekly publication, which only printed in one color. Deeply interested in reproduction technologies, Remington would optimize his work for the particular medium, whether lithography or, in this case, photoengraving.

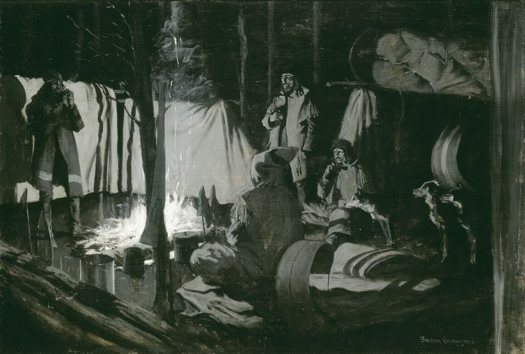

First and Best Camp of the Trip, 1895 [artic.edu]

Critics chided Remington for painting from photographs–and he equivocated about it himself, and periodically claimed to have given up the practice–but it’s precisely this cross-pollination of photography and painting that made Remington’s painting feel so modern. Photography’s role in defining the American West has been explored to death, but I can’t remember Remington ever coming up in those exhibitions or discussions. And yet he was the one who almost literally created the cowboy as an archetype, and it was his images–or the photo-like, photo-processed reproductions of his images–which enjoyed the widest audience and had the most formative influence on the popular culture.

Other painters were using photography at the time, too; Eakins and Sargent both come to mind. But Remington seems to have gone beyond those two in his experimentation. All three treated photos as source documents and reference tools. Remington gets credit for accurately depicting in paint what Eakins’ friend Edweard Muybridge proved photographically: that a galloping horse’s feet all leave the ground at once.

But Remington also explored painting using innovations like flash photography and artificial lighting. And by optimizing his painting for mechanical reproduction instead of naturalistic or visual authenticity, it feels like he took a significant conceptual leap before anyone knew what conceptualism was.

The Art Institute of Chicago has many monochromatic Remington paintings [artic.edu]

This Poeme Electronique Was Brought To You By Philips

Hello, Earth to Le Corbusier archive!

Corbusier conceived Poeme electronique for the Philips Pavilion at the 1958 Expo in Brussels. It was an 8-minute immersive light, film and sound experience which told mankind’s long, hard slog towards peace.

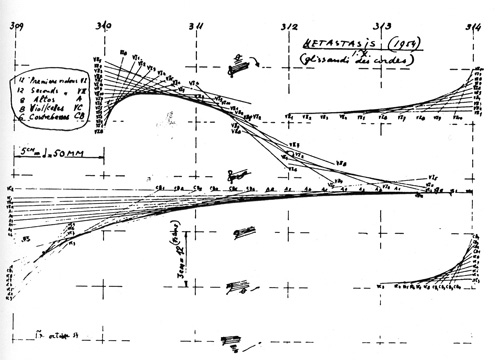

Don’t forget the architecture. The multi-channel version of Poeme electronique, with a score by Edgard Varese, was projected on the walls of the tensile tent-like pavilion, which was designed by composer/architect Iannis Xenakis, who was working for Le Corbusier’s firm at the time. Xenakis recalled–perhaps wishfully, I don’t know–that the parabolic concrete forms came directly from his graph-based score for his 1954 composition, Metastasis. [The piece was staged last March at the Barbican as part of a Xenakis program, concurrent with the Corbusier exhibition.]

Here’s Poeme Electronique in its single channel version:

This brief segment produced in 2000 for a virtual reality recreation of the Poeme Electronique experience also includes period footage, photos, and a couple of interesting looking models from the Philips archives:

Le Corbusier; Iannis Xenakis; Edgard Varèse

«Poème électronique: Philips Pavilion» [mediaartnet.org via things]

previously: E.A.T. and the Pepsi Pavilion, Osaka Expo 70; a lost piece of corporate-sponsored installation art?

Every Abandoned House On The West Robinson Street Strip

![]()

On one block of West Robinson Rd West Robinwood Rd in Detroit, all but five of the houses are abandoned. Jim Griffioen took photos of both sides of the street. His massive, stitched together photos are on Sweet Juniper and his flickr stream. I flipped the south side and combined them, a la Ed Ruscha’s Every Building On The Sunset Strip.

The Singularity [sweet-juniper]

Previously: Every Building on The Sunset Strip–and then some

Apologies to anyone still living on Robinson St.

“Design as money laundering bon-bon.”

Dan has been my main source of Postopolis! LA coverage this year. Design theorist Benjamin Bratton wrapped up the event’s discussion with an interesting, twisted bow of a speech. He talked about “Post,” but in the sense of Post-/Pre-, not the original Post/Comment the conference’s blogger organizers originally imagined.

He hopes we’re Post-Bubble, for instance, but isn’t quite certain:

Because design was a symbol of the bubble it is also a symbol of the bubble’s collapse. Think of OMA’s burned out Mandarin Hotel as the anti-Bilbao.

….

But what also seems clear at least to me, is that very many ways of doing things, of designing things, of consuming things, of consuming design are very likely, to sample Paul Krugman, zombie ideas. Design as money laundering bon-bon. The destiny of the post-Bilbao coke high of Dubai, seems be a psychotic desert ruin.

I hope Jurgen Bey is already working on Murray Moss’s pitchfork-proof panic room.

Benjamin H. Bratton (Postopolis! LA) [cityofsound.com]

Getting Into Trouble With The NY Times

The report this weekend–from Apartment Therapy–about Apartment Therapy getting a takedown notice from the NY Times legal department for unauthorized use of the Times’ IP reminds me of the Apartment Therapy story from June 2004 about Apartment Therapy getting an angry call from the NY Times Home Section writer Marianne Rohrlich.

Rohrlich was pissed at AT’s weekly replication of the Times Home Section content, photos, links and such. AT’s response was to aw shucks about what big fans they are, and to tout the amount of traffic they’re driving to the Times’ site:

“Did it occur to you that it is not right to just LIFT other people’s work?” she asks me. (“Do you know what blogging is?” I want to ask.) “Our legal department is going to be calling you.”

Calling us! Legal department! Whoa!

I had a Shawn Fanning moment. Is this Napster 2004? Are we in trouble?

Now Matt and Andy are on the case, The Case of the Fishy DMCA Martyr Ploy.

DMCA Takedown notice: The NYTimes goes to war, wants to shut us down [at]

Apartment Therapy on Getting Into Trouble [at]

Did I Say Japanese Internment Camps? I Meant CCC Happy Camps!

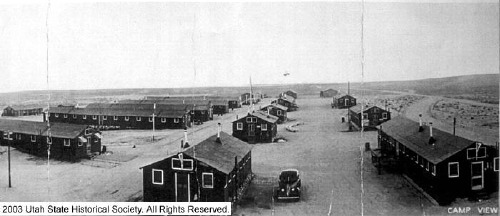

Another thing that caught me off guard looking through piles of photos from the Civilian Conservation Corps, was the camps. My interest in the CCC didn’t come from the New Depression unfolding around us, but from learning over Christmas that while he was in the CCC, my grandfather helped build the Topaz Relocation Center, the Utah internment camp in which Japanese-Americans were interned during WWII.

That Japanese Americans were forced to live in “tar paper-covered shacks” of military design set up in remote, harsh locations is unrefutable evidence of the camps’ punitive, prison-like conditions and an integral element of the entire internment camp narrative.

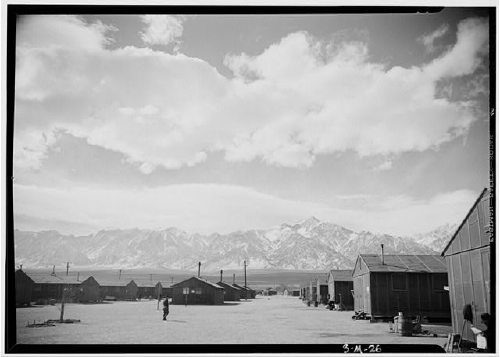

But what I didn’t realize was that is exactly how participants in the CCC lived, too. The image above, cropped from the official photo of Callao Camp in Juab County, just north of Topaz.

Compare it to Ansel Adams’ photo of the barracks at Manzanar below, from the Library of Congress:

Of course, it doesn’t minimize the injustice of being forced to abandon your home and possessions, then being imprisoned in the desert by your own government because of your race. But–and I know it’s hard to have a “but” after a sentence like that–but I have to imagine that the seven-plus-year history of the CCC, along with the experience of millions of Americans who participated in it, along with the Depression itself, had a formative influence on how the internment camps were perceived at the time.

What would public reaction be today if thousands of Pakistani-Americans were ordered to report to a fenced-off city made of FEMA trailers? Would we be outraged at the outrageous violation of their constitutional and human rights, or would we say, in the wake of Katrina, Ike, and waves of foreclosures, “Hey, what’s the big deal? It’s not a prison”?

Civilian Conservation Corps, AKA The Earthworks Progress Administration

Over the holidays, I taped an interview with my great uncle Wayne. He is my paternal grandfather Champ’s older brother. [Yes, I did ask him about my grandfather’s name. His recollection was that my great grandfather Chester Jehiel Allen hated his own name so much, he was determined to give his kids one monosyllabic name apiece. But that’s not the point right now.]

Wayne told me as a young man growing up in central Utah, my grandfather had worked for the Civilian Conservation Corps. The CCC was one of the most successful Depression-era jobs programs; it put hundreds of thousands of men, mostly from rural areas, to work building roads, dams, bridges and national park fixtures, and doing other construction-type projects.

I’ve been surfing around on the history of the CCC in Utah, trying to get a sense for what his experience was like. From newsletters archived by the Utah State Historical Society, it sounds like it was run in a quasi-military style, with camps and barracks and ranks; it’s hard to imagine my grandfather fitting in well.

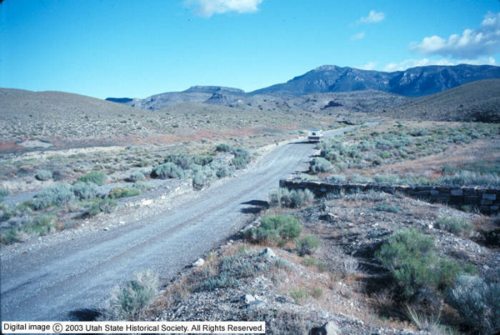

The USHS also has several collections of photographs taken by CCC members, though I couldn’t find any yet from the camps or periods Champ served. The photos show camps or the projects: structures in remote desert landscapes lacking any readily identifiable landmarks. Gabions and walls and foundations of stone in the middle of the desert. Not just bridges to nowhere, but bridges to, from, and in nowhere. Some of them unexpectedly reminded me of Earth Art sculptures.

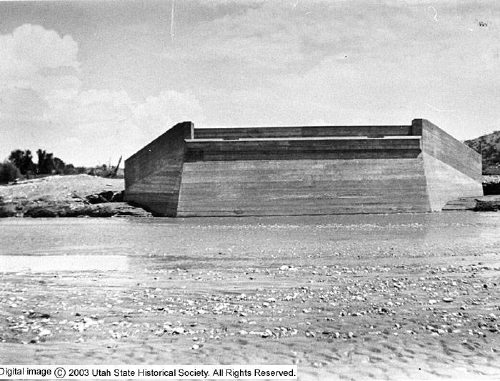

Ashley A. Workman served in the CCC for seven years, 1934-41, in ten different camps. This undated, unsited photo from his collection of “some type of CCC bridge construction project.” What else could a minimalistic geometric structure, stripped of time, place, context, and utility be but a sculpture? [here’s another view of it.]

We know where Lamar Peterson took this photo, “”Dam on Santa Clara River, Shivcoit Indian Reservation,” [actually, I believe that should be Shivwits, a band of the Paiute tribe] but it still looks like it could be part of Michael Heizer’s City.

I have no idea what Heizer, Robert Smithson, Walter deMaria, or any other earthworks artists thought or said about projects like the CCC’s. Maybe nothing at all, ever. We see these historical works from the other end of the temporal telescope now, but did they look different to people encountering them for the first time in the 1960’s and 70’s?

When these artists began conceiving massive sculptural interventions in the remotest desert landscapes they could find, the country was only a generation removed from the Depression. I expect there was a much greater general cultural awareness of the CCC and its built legacy. And then there’s the post-war construction and baby boom that saw American families taking cross-country roadtrips to national parks via new interstate highways.

If anyone’s seen Earthworks discussed well from this historical and aesthetic context, I’d love to know about it. And if anyone’s then looked even further back, with contemporized eyes, to explore the production of pre-minimalist and pre-Earthwork objects, I’d definitely love to know about it, too.

Images 2 of 1455 CCC photos in the Utah State Historical Society Collection [lib.utah.edu]

Cave House Proves There Is Something Like A Dome

So naturally, I was intrigued by the folks in Festus, Missouri, who are forced, by their inability to refinance the note on Caveland, the 15,000-sf sandstone cave they spent five years and all their money and time transforming from an abandoned roller rink/concert venue into a house, and so have listed it on eBay. [via]

And I don’t know where Festus is, but maybe it’d be a nice place to get away to? Doesn’t TWA have a hub in St. Louis? Even though it’s double the price of most every other listing in town, $300,000 still seems like a bargain. I mean did Ike and Tina and Bob Seger play in your cave house?

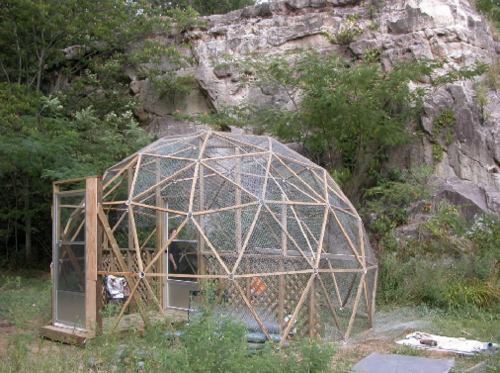

And then I see this big open space in front of the cave, a box canyon, and I think, “You know, that looks like a nice place to put down one of them Buckminster Fuller Fly’s Eye domes…”

So imagine my [non] surprise to find a GeoDome listed first among the Caveland owner’s plans. :

Long enamored with geodesic domes, we envisioned starting with one multi-purpose dome in front of the cave, and later adding a second to separate our office from our living space. We looked at the cave as primarily recreational space and office expansion, with a few commercial possibilities retaining potential.

The evolution from GeoDome to Guinea Dome will be a familiar one to anyone who has endured the never-ending argument between his big dreams and his budget.

“Calder on the Roof”

In 1967 Henry Geldzahler, while lecturing the Women’s Group at the Grand Rapids Art Museum, suggested to Mrs LeVant Mulnix III that the city might do well to install a public sculpture on the plaza in front of city and county buildings being designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. Mrs Mulnix promptly wrote to Congressman Gerald Ford to ask for assistance in obtaining a grant from the newly established National Endowment for the Arts for the commission.

SOM senior partner William Hartmann, who was at that time completing the installation of Picasso’s monumental sculpture in front of the firm’s Chicago Civic Center, came in to consult on the project. Alexander Calder was chosen, and La Grande Vitesse which sits on Calder Plaza, has been the symbol of the city for decades.

Grand Rapids was the beneficiary of the friendship forged between Calder and Mulnix, and in 1974, the artist made a gift to the city of Calder on the Roof, a giant red, black and white mural executed on the roof of the Kent County Administration Building.

The work was intended to be seen from the surrounding buildings, which basically means the adjacent City Hall. Of course, it looks pretty sweet on Google Maps, too.

Misconceptual Misappropriation

Tyler Green Twittered the following from the ICA Philadelphia panel discussion on the 20th anniversary of the Mapplethorpe NEA implosion:

[Rob] Storr coins ‘misconceptual’ art: artists who shortcut to the now via conceptual art without understanding history of conceptualism.

tight, tasty, and much-needed, I like Storr’s definition, but I’m afraid he didn’t coin the term.

Instead, he probably probably got it where I did, from Madelon Vriesendorp, the “playground surrealist” Dutch artist who co-founded OMA with her former husband, Rem Koolhaas. Art Review profiled Vriesendorp last year when her retrospective opened at London’s Architectural Association–the show is at the Swiss Architecture Museum – Basel through June 2009:

In Vriesendorp’s “city” of objects upstairs at the AA, you’re confronted, stared-down, and overwhelmed by a vast army of touristy trinkets: nuns, skeletons, plastic food, multiple iterations of the Statue of Liberty, aliens, snowglobes, robots, cowboys, hindus, buddhas (on phones and with headphones), body parts – especially feet, hands, tongues and eyeballs – monkeys, flies, lady birds, centipedes, snakes, and buildings, buildings, buildings caricatured and reduced to their essence in little cute models meant for the mantelpiece back home. Vriesendorp has said that she’s only interested in failed objects, and that in her global city she feels like a tourist who has been given the wrong directions, misheard them and ended up in the right place anyway. She calls this practice “misconceptual art”.

Misconceptual art: The World of Madelon Vriesendorp [artreview.com via things]