So sweet. Check out this awesome aluminum-clad house, which curator/architectural historian Erik Neil spotted yesterday on the campus of the NY Institute of Technology:

I looked it up on the Internet, and found this post, which I wrote last weekend. It’s Lawrence Kocher and Albert Frey’s Aluminaire House as it exists today, or yesterday, anyway, which is pretty damn close.

This house is completely fantastic. Who’d have thought that looking like a 1930’s industrial refrigerator would result in such wonderful architecture? Put some quilting on those aluminum panels, and it’d be like living at Florent.

Neil visited the house because he’s including it “Arcadia to Suburbia: Architecture on Long Island 1930-2010,” an exhibition on the history of modernism on Long Island set to open in January at the Hecksher Museum in Huntington.

He also pointed out that Joe Rosa, who was a key player in saving the Aluminaire House from demolition in the 1980s, included it in his 1990 monograph, Albert Frey, Architect, which I have somewhere in storage, but which I might sell just on principle because–hello–it’s like $115-$581 on Amazon right now. Crazy days.

Category: architecture

DDOS Cannot Silence Awesome Christopher Hawthorne LiveTweet

LA Times architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne delivered a mordantly hilarious stream of live Twitter updates from a Sci-Arc panel discussion last night. I’ll be damned if I can comment on it, and I’m not sure I can even link to it all, but it is awesome.

The show started with Anthony Vidler talking old-school Freudian smack–complete with accent–about Schindler/Neutra, Neutra/Schindler, or vice versa. And then he moderated a “architects in LA”-type discussion among Hitoshi Abe, Peter Cook, Eric Owen Moss, Thom Mayne, Peter Noever, and Wolf Prix.

My favorite is right toward the end *SPOILER ALERT*: “The philosophical–not to mention gen.–homogeneity of panel is astounding. Guess that was predictable, but still. Hoping Hitoshi Abe can……rescue us from Boomer avant-gardism.”

Help me, Hitoshi Abe, you’re LA’s only hope. I hope Sci-Arc puts this thing on YouTube…

Schindler / Neutra, Neutra / Schindler; L.A. / Wien: On the Couch [sciarc.edu]

And Now A Report On The Latest Trends And/Or Story Ideas From The World Of Architecture!

The funny thing is, I think my problem is I couldn’t have made something like this up:

Hi Greg,

Here’s a trend and story idea for the growing number of architecture company cars piling up from economic downsizing: The majority of small businesses and firms lease cars for tax purposes. However, owners must still make payments on those cars if the leases are stuck in park from staff cutbacks. But a new program is now helping small firms get unused car leases off the books giving finances a new lease on life.

–Small business owners have had to downsize staff, leaving many of these car leases sitting idle in the parking lot (but still requiring monthly payments).

–Owners can’t sell the lease and if they turn them back in to the bank they will get slapped with early contract termination fees upwards of $10,000 per car.

–A new Small Business Car Release program helps architecture firm owners ditch the lease by transferring the contract to someone else (most popular service being PressReleaseSender.com).

–The car lease company is involved in the program, it takes about 2-3 weeks for the transfer and removes the small business owner from obligations to make the monthly payments.

–Paying for unused car leases is salt on the wound considering rising health care costs and less credit available from banks.

Sources To Quote:

–Sergio Stiberman, CEO and founder of PressReleaseSender.com, to discuss the new Small Business Car Release program.

–Also speak with the executive director of Auto Fleet Leasing on industry trends and number of small businesses leasing vehicles.

Additional Story Titles:

Company Helps Small Business Unload Excess Car Leases

Small Business Help Allows For Immediate Release of Company Cars

Small Business Relief When Company Car Can’t Start Up

Program Helps Small Business Move Company Cars Stuck in Park

Program Offers Small Business Relief for Unused Car Leases

Unemployment Leaves Small Business on Company Lease Collision Course

Unused Company Car Leases Eat Into Already Thin Margins

So many wonderful titles to choose from, I need an intern to help me decide!

Lawrence Kocher’s Black Mountain College?

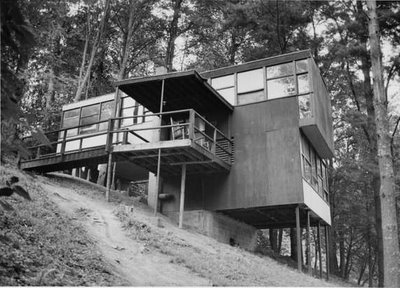

I stumbled across Lawrence Kocher and Albert Frey’s Aluminaire House last night while trying to figure out who built this house at Black Mountain College. It’s from the Charles Olson Research Collection at UConn, and was posted at An Ambitious Project Collapsing [get some permalinks there, buddy!]

Olson ran BMC from 1951 until its closing in 1956. But though it’s in the Olson BMC portfolio, the photo is credited to Frank Ballard, and is dated 1977, and is taken at a place called Camp Rochmont. So what gives?

Well, Camp Rochmont is actually Camp Rockmont, a non-denominational Christian boys camp, and it is Black Mountain College. When the school closed, 550 acres around Lake Eden was sold and turned into the camp. Another 60 acres full of BMC buildings is now Lake Eden Events, which hosts concerts and gatherings large and small.

As editor of The Architectural Record, A. Lawrence Kocher had recommended to BMC in the late 1930s that they collaborate with Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer, fresh from the Bauhaus, to design a new modernist campus at Lake Eden, a failed, half-built resort complex. When fundraising fell through, Kocher himself began designing a building and planning out the rest of the site beginning in 1940. He was apparently in residence from 1940-43, teaching architecture and leading BMC’s trademark student building projects.

Of all the architects associated with BMC, Kocher seems the most likely architect for structure above. He designed two houses in 1940-41: one for the music teacher, the Viennese composer and early Schoenberg student Heinrich Jalowetz [now called the Sequoia Cottage, and available for $250/night, but not this year], and a 2-story house “for the kitchen staff and other black workers.” [It was still the segregated South, after all.

In The Arts at Black Mountain College, Mary Emma Harris described the Jalowetz house design as “based on four-by-eight-foot plywood panels,” a favorite material of Kocher’s. As the picture clearly shows, the house above is also designed around plywood sheet dimensions. And don’t the raised base and ribbon windows kind of give off an Aluminaire vibe?

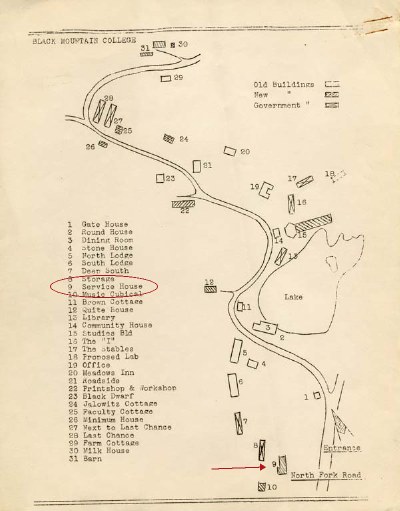

The only house on this map of the Lake Eden Campus I can map it to is #9, the Service House, which is indeed on the Rockmont side of the lake.

For all its seemingly awesome, modest simplicity, something called a Service House, built for staff in a far corner of BMC sounds unlikely to have much more documentation–and probably doesn’t appear too often in the typical photographic record of the day. I’m not too optimistic about finding out much more, but I’d love to be wrong.

Who What? Kocher & Frey’s Aluminaire House?

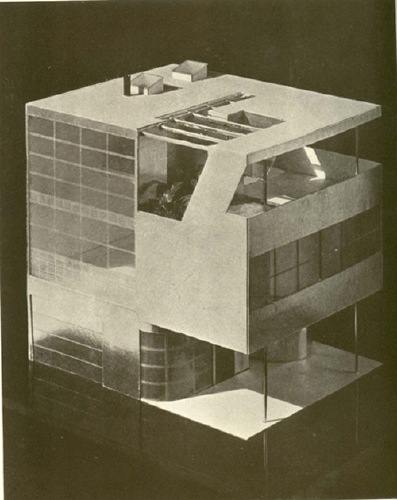

Let me get this straight: the first modernist prefab in the US; one of two US houses included in Phillip Johnson’s 1932 International Style exhibition at MoMA [the other: Neutra’s Lovell House]; built in 10 days from off-the-shelf industrial materials, with no formal plans or blueprints; Albert Frey’s first US project; bought and disassembled in hours, then saved and bastardized by Wallace K. Harrison; quoted nearly perfectly–concept, materials, and form–by Kieran Timberlake in their Cellophane House; and yet somehow Aluminaire House itself was not included in “Home Delivery,” MoMA’s 2007 show on the history of the modern prefab Please tell me I just missed it or blocked it from my memory.

But I’m hardly the only one.

Lawrence Kocher was editor of Architectural Record and later involved with Black Mountain College. The 27-year old Albert Frey was fresh off the boat from Le Corbusier’s studio. They whipped up Aluminaire House from donated parts and materials for a 1931 building show and Architectural League exhibition at Grand Central Palace, an expo hall that filled the block between 46th and 47th streets and Park and Lex.

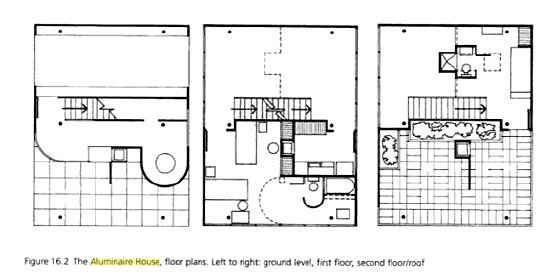

Kocher’s concept was a light-filled, modernist prefab house made of innovative, industrial, mass-produceable materials: aluminum, steel and glass. The 3-story, 5-room, 28×22-ft, 1,200 sf building was barely more than a mockup, an exhibition pavilion. Frey later compared it more to a refrigerator than a building in its construction; it was light steel bolted together with nuts and washers and skinned in ribbon windows and corrugated aluminum, a material Frey would use extensively in California. The floor was ship decking covered in linoleum. Interior walls were rayon fabric. It was supported on five aluminum pilotis.

The main living space [LR/DR, Kit, MBR, BA] was on the second floor. The living room was double height, open to a partially enclosed library/2nd bedroom on the third floor, which also had a terrace. A second bathroom with shower was cantilevered over the living room, which frankly sounds like a joke.

Harrison bought the Aluminaire House for a thousand dollars after the expo ended, and reassembled it at his house on Long Island. In ’32, Johnson showed the house in the International Style exhibition, but didn’t include it in the catalogue. Harrison proceeded to enclose the ground and third floors and add on some circular structures, rendering the house nearly unrecognizable.

Which is why it was almost demolished in 1987-8 when Harrison’s estate was chopped up and developed. The architecture department of the New York Institute of Technology took the Aluminaire House on as a school project. They studied and dismantled it, then eventually reassembled and restored it on a new pad on their Central Islip campus. Which looks to be about 10 minutes south of Exit 55 on the LIE, within easy pilgrimage visiting by every design snob in the Hamptons.

And yet, no one really seems to care or know about it. In a brief blurb about a 1998 Arch. League show on restoring Aluminaire House, Herbert Muschamp got the location and story of the house wrong. No one who writes about it sounds like they’ve actually seen it. There aren’t any contemporary photos of it online, only one shot from Harrison’s yard.

It’s on Google Maps, of course, and that’s Microsoft’s Bird’s Eye view on the right. But no mention of it on NYIT’s site. [The architecture department was moved from Islip to a campus in Old Westbury, so if it served any academic purpose before, the Aluminaire House seems kind of orphaned now. A 2007 messageboard post said that it was to be relocated as part of a redevelopment/selloff of part of the campus. If it hasn’t happened yet, I’m sure it won’t happen for a while.

But it sounds to me like there’s an unloved, unappreciated pile of historic modern awesomeness in the middle of Long Island that needs to be liberated and returned to loving domestic use. At the very least, will someone take half an hour on the way to the beach and go shoot some freakin’ photos?

The only lengthy discussion of Aluminaire House I can find online: docomomo’s 1998 Modern Movement Heritage by Allen Cunningham [google books]

Microarchitecture On ebay.fr, Only Two Days Left!

Estuaire is the three-time biennale in beta for the Nantes region. This year, the second incarnation includes I.C.I., Instant Carnet Island, a habitable, riverfront collection of micro-architecture which is for rent–EUR10/person/night, bring your sleeping bag–and for sale.

Several of the structures have been put on French eBay. Available items include both Antonin Sorel’s L’étoile de l’amour [above, left], which is several puns at once on L’étoile de la mort [the Death Star, though in Star Wars ep. IV, it was actually called l’Etoile Noire]; and Damien Chivialle’s ark for “amoreux hedonistes” [above, right]; but not, alas, Ant Farm’s time capsule/video lounge recreation of their Media Van [above, center], which could probably teach the kiddies a thing or two about hedonistes, amiright?

There are less than two full days left, and so far, with only one 16-seat picnic table by the Dutch design firm 24h Living meeting the reserve, the whole thing seems destined to be a primarily conceptual exercise.

Unless people start bidding now!

The Flake House [above, currently EUR2310] by the Paris architects OLGGA is pretty rustic-slick, about as practical as a folly can get; and Dre Wapenaar’s Treetent [current bid: EUR2000] is a classic. But I think I’d take Spanish artist Alicia Framis’s Billboard House [top] first. The opening bid is just EUR1000 [including breakdown and loading, but not shipping or reassembly].

Originally conceived for the Land project Rirkrit Tiravanija organizes in Thailand, Billboard House consists of just three billboards and a raised floor. It threads the utopian needle very nicely. It’s unprecious and low-tech, a totally plausible-seeming affordable housing solution–for folks living the Thai, along the side of the road, do all your cooking and socializing and hygienic activities outdoors lifestyle.

Estuaire 2009 | Instant Carnet Island runs through Aug 16 [estuaire.info via thingsmagazine]

check out Estuaire09’s items on eBay France, auctions end July 31 Paris time [ebay.fr]

Billboardhousethailand (2000) [aliciaframis.com]

update: in the end, everything had at least one bid, but only two of 24h Living’s three tables sold.

Julius Shulman Is Dead! Long Live Julius Shulman!

Like everyone else, I see modern architecture–the whole modern world, or at least the West Coast of it–in glorious black and white, thanks to Julius Shulman. Just as Hugh Ferris’s smoky charcoal skyscraper renderings defined Gotham a generation earlier, Shulman’s has been the formative, definitive lens through which postwar Los Angeles has been seen and understood.

So even as I miss him in one human sense, I’m kind of relieved he’s finally gone. Now maybe a new perspective of modernism has a chance to take hold. Or maybe an old one, who knows? Just something, anything besides relentless Shulmanism.

Christopher Hawthorne has a couple of open-eyed remembrances of Shulman and his double-edged relationship to the city he documented so long and loved so much:

Shulman’s vision of modern, stylish domesticity was in many respects an airbrushed one. It’s hard to believe anybody actually ever lived the way the carefully posed models in his photographs seemed to, carrying a tray out onto a poolside terrace, or sitting in perfectly pressed suits and dresses on the edge of a Mies van der Rohe chaise longue, city lights twinkling in the distance.

But his images were impossible to resist as a kind of mythmaking, even for the most tough-minded observers of life in Los Angeles. To look for any length of time at a Shulman picture of a great modern L.A. house is to get a little drunk on the idea of paradise as an Edenic combination of spare architecture and lush landscape.

Hawthorne also wrote another, more personal reminiscence of Shulman:

He was known for a certain blunt irascibility by that point in his life – he was 94 when we met, for God’s sake – but I never saw that side of his personality. He was dogged in his view that life in Los Angeles, as he told me once, was “simply glorious,” and that put him at odds with the generation of photographers, architects and artists who followed him, many of whom were more interested in exploring a grittier, less elevated vision of what it meant to be here.

The one time I met Shulman was after a public event, where his cantankerous charisma was turned up to 11. It was impossible not to be rooting for him all the way that night, even though I kind of regretted it in the morning.

That phrase, though, about others who “were more interested in exploring the grittier, less elevated vision of what it meant to be here [i.e., in Los Angeles]” gets to me. Hawthorne saw Shulman as a promoter; I’d probably go with evangelist. But the point is, sometimes it’s not a matter of exploring what it means to be someplace, it’s a matter of just being there and seeing what’s around you. It’s like Shulman knew what he’d see before he ever got there.

You Had Me At Muschamp in Monaco

Herbert Muschamp in a giant weather balloon movie in Monaco WHAT?

This is something we did in Monaco where we put Herbert Muschamp’s text, “Bubbles in the Wine,” to film. It was my job to go out and find these weather balloon manufacturers that had these funny-shaped screens that had projectors inside them. And what Peter with Imaginary Forces did was to figure out how to cut a nine-screen film simultaneously so you sometimes get a single image, you sometimes get multiple images on the balloons.

That’s Greg Lynn, speaking last year at MoMA’s “Design and the Elastic Mind” exhibition, as presented by Seed Magazine.

Sure enough, he wasn’t making it up. In 2006, Germano Celant brought in Lisa Dennison to help curate, “New York, New York,” a giant summer show at the Grimaldi Forum. Lynn, Imaginary Forces, and UN Studios worked as United Architects, the collaborative they formed for the World Trade Center rebuilding competition.

Here’s the brief:

UA created an immersive space that told the story of the last 50 years of New York Architecture through an animated narrative, scripted by Herbert Muschamp. Eight synchronized films and a uniquely New York soundtrack told a story of the past, present and future of the city. By suspending eight 20-foot balloons with interior projection from the ceiling and walls, IF transformed the balloons into a new architectural media delivery system.

And here’s IF’s quick making of video, which Warner Music Group unceremoniously stripped the soundtrack from:

Hmm. First off, this all sounds straight from the Eameses’ expo playbook. Their collaboration with George Nelson, for example, at the 1959 American National Exhibition in Moscow. Glimpses of the USA was a 7-screen film epic of American material awesomeness, shown in a dome pavilion, and designed to blow hapless Commie minds. [My mind was blown a little bit just by this photo of the Eameses standing inside a mockup of the pavilion. via]

And of course, the Eameses went on to make approximately one million movie/slide/multimedia presentations and exhibitions for IBM, a format which was later cloned in every Park Service visitors center I went to as a child. So on the bright side, there’s no need for a proof of concept!

All told, the installation as realized, with the balloon screens seemingly dispersed on either side of the narrow, Nauman-esque exhibition space, doesn’t seem to have quite the impact that UA originally imagined. Check out the drawing over Lynn’s shoulder above, where the balloons are all clustered like sperm around an invisible egg. [Which would have been you, by the way, the viewer. You were the egg. And Joe Buck was the sperm. Muschamp is whooping in Heaven right now at the thought, I’m sure.] Point is, the panoramic wall is closer to what UA realized in their “New City” installation at MoMA.

Meanwhile, there’s not much online about “New York, New York,” which was subtitled, “Cinquante ans d’art, architecture, photographie, film et vidéo.” From the Art in America writeup, it sounded like a sprawling mess and a bit of a trophy dump, not necessarily a bad thing. Of course, half the article is about expo logistics and insurance and transporting masterpieces [sic], so who knows? Also, I can’t find this Muschamp “Bubbles” essay anywhere online. Please tell me someone somewhere’s working on a collected works.

Monaco starts around 3:30: Seed Design Series | Greg Lynn: New City [seedmagazine, thanks greg.org idol john powers for the tip]

Experience Design | Bubbles in the Wine, 2006 [imaginaryforces.com]

House On The Moon On The Ericsson Globe

Josh Foer is on fire, and I’m like a moth to the flame. Foer’s guestblogging at BoingBoing, and is just lobbing up one crazy-awesome megasphere after another. It was his charticle in Cabinet a while back about the history of giant spheres that introduced me to satelloons in the first place.

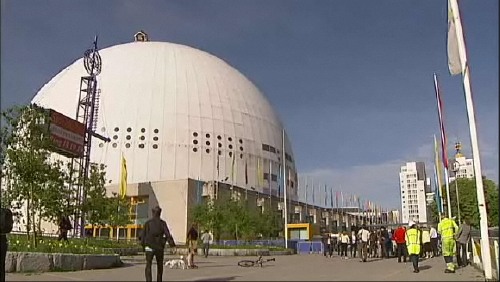

So it’s no surprise that he surprises me again with an offhand reference to the Globe Arena in Stockholm, which is just “the largest spherical building in the world.” And it also happens to be at the center of the Sweden Solar System, the world’s largest scale model of the solar system, where Pluto is a ball 300km away.

No, the Globe, which Ericsson just paid to have renamed the Ericsson Globe, also has a small stuga, a traditional red Swedish cottage stuck on top of it for the summer.

A month ago, the Swedish artist Mikael Genberg, whose primary medium seems to be the traditional red Swedish cottage, attached one to the Globe in preparation for his much larger project, which is to dispatch a traditional red Swedish cottage-building robot to the moon in 2012, and have it build a traditional red Swedish cottage there. On the moon.

I’m not sure how this syncs with the Sweden Solar System, where I assume the 100-m diameter Globe is standing in for the sun, not the moon, but the visuals are pretty irresistible.

Sweden Solar System [atlasobscura.com via boingboing]

Ericcson Globe, aka Stockholm Globe Arena [wikipedia]

houseonthemoon.com project blog [houseonthemoon.com]

MikaelGenberg.com [insane, optimized for Netscape 4, unclickable]

Swedes sending robot to the moon to build nice little cottage [gizmodo.com]

image and video: Röd stuga på Globens topp [svt.se]

Les Ballons du Grand Palais

The Grand Palais was already the best of the three venues in the world capable of accommodating my Satelloon project–a re-creation of NASA’s Project Echo (1960), the 100-ft metallic spherical balloon which was world’s first communications satellite, and which was also known as the most beautiful and most-viewed object ever launched into space–but now it’s practically inevitable.

Unless someone tells me that the Pantheon or Grand Central Station have already hosted legendary air shows dating back a hundred years…

These photos from Branger & Cie via the Smithsonian show balloons and blimps on display at the 1re Exposition Internationale de Locomotion Aerienne, which debuted in the nave of the Grand Palais in September 1909. They ran until 1951. Which makes bringing back the spirit of the Air Show both spectaculaire et logique!

Previously: Les Satelloons du Grand Palais]

Giant Satelloon-Shaped Downtown Megastructures I Haven’t Known But Loved

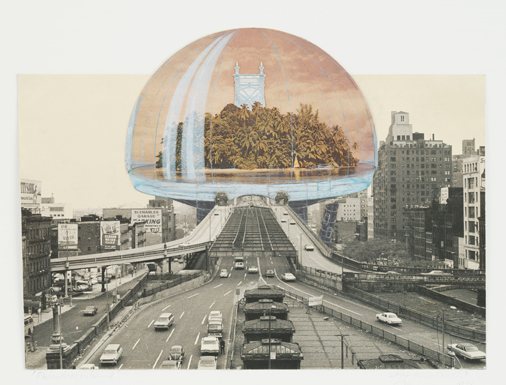

I can’t find any details online about this “Downtown Megastructures” image by Klaus Pinter and his colleagues in the Austrian architecture collaborative Haus-Rucker beyond what sokaris73 put in the flickr caption: it dates to 1971, and was apparently included in a 2000-1 show, “Radical Architecture,” which traveled from Dusseldorf and Koln to Villeurbanne.

MoMA showed a similar-looking 1971 gouache/photo collage last year, though, in Andres Lepik’s “Dreamland: Architectural Experiments since the 1970s”. Titled Palmtree Island (Oasis), it’s a dome island [an Uptown Megastructure?] super-imposed on Nervi’s 1963 bus terminal at the George Washington Bridge.

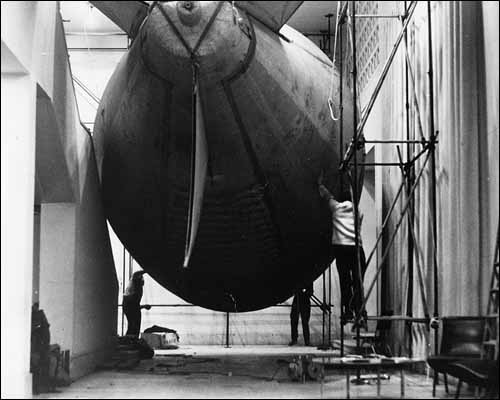

Seems the 60’s and 70’s love affair with inflatable architecture was not just contained to America and the nude Stones fans at Ant Farm. In 1968, the Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris showed “Structures Gonflables,” a giant show of blow-up design and architecture. Not big enough, though, if this photo of a dirigible blimp being stuffed into the museum is any indication:

Coming at this balloon genre from the NASA point of view–not to mention the corporate and government world’s fair pavilions point of view–it’s beyond ironic that inflatable megastructures were often considered embodiments of anti-establishment, countercultural ideology. The Architectural League had a traveling exhibition on the subject in 1998, “The Inflatable Moment: Pneumatics and Protest in ’68,” which Metropolis Magazine wrote about at the time. Good stuff.

Daniel Libeskind The Least Surprising Prefab Architect In The World

Bwahaha, if ever there were an architect whose work looked like it was all churned out of an idea factory from weary bins full of identical parts, it’s Daniel Libeskind. And sure enough, just in time for the prefab business to be declared dead, the NY Times reports that Libeskind has unveiled a “limited artistic edition” 5,500-sf prefab villa, which can be yours–installed, in Europe–for just EUR2-3 million apiece.

Mr. Libeskind says he was involved in every aspect of the design, from the door handles to the kitchen layout to the placement of a barbecue area.

…

“We never really wanted it to be a prefab,” Mr. [Michael] Merz [spokesman for the Berlin company distributing the villa] said. “We want to position this as a piece of art.”

Buyers will also be promised regional exclusivity, ensuring that they are the only ones in their neighborhoods with the design.

And don’t forget, everything’s symbolic! There are no renderings of The Barbecue Of Community, but here’s a picture of the Sectional Sofa of Solace, criss-crossed by the Zig-Zags of Enlightenment.

The size, too, is important, 5,500 equaling both the number of passengers on the ship little Danny sailed into New York Harbor on as a boy, and also the drop in the Dow since the project began.

Libeskind Designs a Prefab Home [nyt via curbed]

The [Latest] Death Of Prefab

Christopher Hawthorne writes about the latest trend in prefabricated modernist architecture: going out of business.

Michelle Kaufmann, Marmol Radziner, Empyrean…

Apparently, when you design houses for a perennially small niche, build them at a cost premium, and no bank will provide loans for them, it’s hard to make a go of it in a depressed real estate market. Who knew?

Prefab movement needs to rethink its model [latimes via christopher’s twitter]

DC’s Underappreciated Modernism: The Great Flight Cage @ The National Zoo

There’s not much of it, and it has some rather determined enemies, so when modernism happens or survives in Washington DC, it feels like somewhere between a happy accident and a miracle.

Or maybe it’s just me. It’s taken me five years of visits to the National Zoo–a five minute walk from our place in DC–to open my eyes to the awesome rarity that is the Great Flight Cage.

Not to say I didn’t notice and like it sooner; its functional yet elegant structure is a standout. From the striking arches; to the curved concrete entrance hut and its twin inside, which serves as a coop of some kind; to the struts under the footbridge connecting the aviary to the banal brick box of the Bird House; it feels like an understate, especially successful, early Santiago Calatrava–from the engineering days, before he got so showy.

The Great Flight Cage was finished in what turned out to be a Golden Age of Aviary design, 1964. And yet, does anyone know who designed it? Do we sing their praises? No. Near as I can tell, the architect was Richard Dimon at the firm of Daniel, Mann, Johnson and Mendenhall. DMJM was awarded a major expansion project for the Zoo by the Smithsonian, which included the aviary and remodeling the Bird and Antelope Houses.

But the archives of the Washington Post contain no discussion of the aviary’s architecture, and barely ever acknowledges its existence at all, except to mention its initial cost and its completion. And that silence seems to have echoed beyond DC.

At the same time Dimon was designing the National Zoo’s aviary, Lord Snowdon, Cedric Price, and Frank Newby were finishing the angular Snowdon Aviary at the London Zoo. And Buckminster Fuller was building a large geodesic dome for the New York World’s Fair which would become the aviary for the new Queens Zoo, and which would be dubbed one of the great interior spaces of New York.

As the link above shows, Dimon appears to have left architecture behind and taken up landscape painting. Though his brief bio says he has designed “many buildings” in the Washington DC area, the only ones I can identify are at the zoo. And the only one of those that’s any good is the aviary, and it’s spectacular.

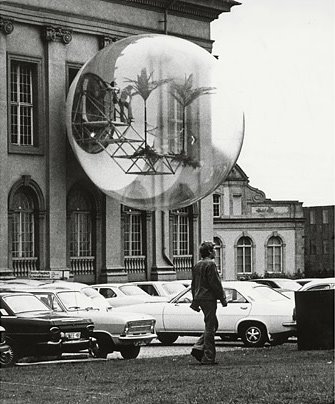

Oasis 7, Haus-Rucker, Documenta 5

In 1972, the Austrian architecture collective Haus-Rucker installed Oasis Nr 7 at Documenta 5.

A steel pipe structure was cantilevered out the window of the Friedericianum, and a platform, two palm trees, and a hammock were installed. The entire thing was enclosed in an 8-meter translucent vinyl bubble.

Oasis 7 was re-created last September It was built on a fake Friedericianum facade at the Victoria & Albert Museum for the exhibition, “Cold War Modern: Design 1945-1970.

Haus-Rucker project archive [ortner.at]

Time lapse making of video: Oasis 7 in the Victoria & Albert Museum [iconeye.com]

via atelier, where I’ve been lifting all sorts of interesting things this week.